Abstract

Protease enzyme has lot of commercial applications, so the cost-effective production of protease using sunflower oil seed waste was carried out from Oerskovia xanthineolyitca NCIM 2839. The maximum protease production was after 24 h of incubation with 2.5 % oil seed waste concentration. O. xanthineolytica was found to produce two proteases—P1 and P2. The proteases were purified using 60 % cold acetone precipitation and DEAE-cellulose ion exchange chromatography. SDS-PAGE revealed molecular weight of P1 and P2 was 36 and 24 kDa, respectively. P1 and P2 were optimally active at pH 7.0 and pH 7.5 at temperature 35 and 40 °C, respectively. Analysis of hydrolyzed product of P1 and P2 by HPLC reveals that the P1 has endoprotease and P2 has exoprotease activity. The treated soy milk with immobilized proteases showed increased shelf life and removal of off flavor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Proteolytic enzymes constitute one of the most important groups of commercial enzymes. These enzymes have ample utilization in industrial processes, such as the detergent industry, a major consumer of proteases, as well as food and leather industries (Kumar and Takagi 1999; Gupta et al. 2002). Proteases are ubiquitous enzymes occurring in wide diversity of species including plants, animals and microorganisms. The vast range led to numerous attempts to exploit their biotechnological applications and established proteases as one of the major groups of industrial enzymes (Rao et al. 1998). Proteases are involved in numerous biological functions, such as septum formation, sporulation, protein turnover, catabolite inactivation, protein secretion and nutrition (Van Tilburg et al. 1984; Godfrey and West 1996).

Microorganisms are the most preferred source of these enzymes in fermentation bioprocesses not only because of their fast growth rate, but also for their ability to engineer genetically to generate new enzymes with desirable abilities or simply for enzyme overproduction (Rao et al. 1998; North 1982). Microbial proteases play an important role in biotechnological processes and they account for approximately 59 % of the total enzymes used (Spinosa et al. 2000). Proteases are produced by wide range of microorganisms including bacteria, molds, and yeasts. Among bacteria, the genus Bacillus predominantly produces extracellular proteases (Godfrey and Reichelt 1985). O. xanthineolytica was potentially known for its ability to produce alkaline protease (Saeki et al. 1994) and thermotolerant chitinase (Waghmare and Ghosh 2010).

Protease production depends on many factors, such as the growth rate of the culture and the composition of the medium plays important roles (Johnvesly et al. 2002). Carbon and nitrogen sources at high concentration were considered detrimental factors in protease production (Frankena et al. 1986). Several studies had reported that proteins and peptides were necessary for effective protease production (Drucker 1972). Some work reported better protease synthesis in the presence of glucose as a carbon source (Gessesse and Gashe 1997). Other medium compounds, such as metal ions and phosphorous source, may also affect the amount of enzyme formation. Several reports have suggested that proteins from the food stuffs hydrolyzed by proteolytic enzymes lead to formation of bioactive peptides (Maestri et al. 2016; Mora et al. 2016; Moughan and Rutherfurd-Markwick 2013). In this study, attempt has been made for the economic production of protease from Oerskovia xanthineolytica NCIM 2839 using oil industry solid waste and immobilized protease used for the improvement of soymilk quality such as flavor and shelf life.

Materials and methods

Microorganism and culture conditions

Oerskovia xanthineolytica NCIM 2839 was obtained from the National Collection of Industrial Microorganisms (NCIM), Pune, India. The culture was maintained on nutrient agar (Peptone 1.0 %, Beef extract 1.0 %, NaCl 0.5 %, Agar powder 1.5 %) at 4 °C and subcultured after every 15 days.

Analysis of sunflower oil industry solid waste

Chemical analysis of waste was carried out to determine protein, fat, moisture, ash and total sugar using standard protocol described by Egan et al. (1981). The protein content was determined by microKjeldahl method, moisture content by oven drying method, fat content by Soxhlet method, total sugar by phenol–H2SO4 method.

Protease production

The protease production was carried out by submerged fermentation technique. Medium used for the protease production contains K2HPO4 0.1 %, MgSO4 0.05 %, FeSO4 0.001 %, sunflower oil solid waste 2.5 % and distilled water 100 ml (pH 7.0). The 24-h-old fresh culture of O. xanthineolytica NCIM 2839 was inoculated in conical flask containing 100 ml medium. The flasks were incubated at 30 °C and protease activity was monitored after every 6-h interval for 30 h. To study the effect of waste concentration on production of protease in the medium, the production was carried out at various concentrations of waste such as 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, and 3.0 %.

Purification of proteases

All steps of purification were carried out at 4 °C. The growth of O. xanthineolytica was inoculated in medium with 2.5 % sunflower oil industry solid waste. After 24 h incubation at 30 °C, the broth was centrifuged at 2795×g for 20 min to obtain cell-free medium. This was then subjected to precipitation using 50 % cold acetone. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 11,180×g for 30 min, dissolved in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer of pH 7.0 and dialysed against the same buffer. The enzyme was further purified by DEAE-cellulose column chromatography, and the column was eluted with NaCl gradient from 0.1 to 0.5 M concentrations, and fraction of 5 ml was collected at the flow rate of 1.0 ml min−1. All the fractions were checked for their protein content by the method of Lowry et al. (1951) and also for protease activity. The fractions showing protease activity were used further for characterization.

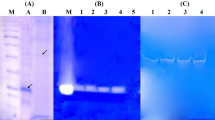

SDS-PAGE analysis

Purity of the fractions, showing protease activity, was checked by SDS-PAGE by the method of Laemmli (1970). The bands were visualized by silver staining technique (Merril 1987). The molecular weight of proteases was determined by comparison with standard molecular marker proteins (Phosphorylase b 98 kDa, bovine serum albumin 66 kDa, Ovalbumin 43 kDa, carbonic anhydrase 29 kDa, Soyabean Trypsin inhibitor 20 kDa).

Enzyme assay

In the protease activity assay, P1 and P2 enzymes (0.5 ml) were mixed with 2.5 ml of 0.5 % casein in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) and incubated at 30 °C for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 5 ml of 0.19 M trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The reaction mixture was centrifuged and resultant soluble peptide of supernatant was measured with tyrosine as the reference substance (Liang et al. 2006). One unit of protease activity is defined as the activity that releases 1 µmol of tyrosine in 1 min at specified conditions.

Effect of pH and temperature on protease activity

The effect of pH on enzyme activity of P1 and P2 protease was studied at various pH ranging from 3.0 to 10.0 using different buffer systems. The buffers used for the purpose were 25 mM citrate (pH 3.0–5.0), 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.0–8.0), and 25 mM glycine–NaOH (pH 9.0–10). The optimum temperature for enzyme activity was determined by assaying residual enzyme activity at various temperatures from 10 to 80 °C. In the temperature stability study, the enzyme was kept for 24 h at the 10–70 °C and residual activity was measured.

Effect of different metals ions on protease activity

The proteases P1 and P2 were pre-incubated in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer having pH 7.0 and 7.5 for the respective enzymes along with metal ions Fe3+, Hg2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Mn2+ using their respective water-soluble salts at 5 mM concentrations. The residual activities of P1 and P2 were checked by standard assay as mentioned above.

Analysis of hydrolysed products

The purified P1 and P2 enzymes were separately incubated with casein, as stated in enzyme assay section. After a 10-min incubation period, products were analyzed by HPLC (Waters 2690 System) using C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm). Elution was done with 70 % acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1, which was monitored by measuring UV A 220 with a Waters Lambda-Max model with LC Spectrophotometer.

Immobilization of enzyme and use in soy milk preparation

The enzyme was immobilized in calcium alginate beads according to the method described by Ates and Mehmetoglu (1997); in this method, 8 ml of sodium alginate solution (3.75 %) was mixed with 2 ml of partially purified enzyme solution (10 mg ml−1) to form a homogenous final alginate concentration of 3 %. The mixture was extruded drop by drop into 0.2 M CaCl2 solution at 4 °C to form beads using a sterile hypodermic syringe needle. The beads were allowed to harden in the CaCl2 solution for 2 h. The resulting spherical beads were washed with sterile distilled water. The beads were stored in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 4 °C. Soymilk was prepared according to the method described by Gatade et al. (2009). The prepared soymilk was treated with immobilized enzyme and incubated at 30 °C for 1 h. Then treated milk was compared with control milk (untreated) for organoleptic characteristics such as color, texture and flavor.

Statistical analysis

Results obtained were the mean of three or more determinants. Analysis of variance was carried out on all data at p < 0.05 using Graph Pad software (GraphPad InStat version 3.00).

Results and discussion

Proximate analysis of sunflower oil seed waste

The sunflower oil seed waste used for the protease production was analyzed for protein, total sugar, fat, and ash content. The obtained results are shown in Table 1; sunflower oil seed waste was found to be rich in carbohydrates, protein, fat, and minerals, which can act as a good medium for the growth of microorganisms.

Production of protease

O. xanthineolytica NCIM 2839 was found to produce extracellular proteolytic enzymes in the presence of sunflower oil seed waste as carbon and nitrogen source. Similarly, De Azeredo et al. (2006) have used feather meal and corn steep liquor for thermophilic protease production from Streptomyces sp. 594. The protease activity in supernatant was increased up to 24 h as incubation time increased; after 24 h, the activity decreased sharply, as shown in Fig. 1. It is vivid from Fig. 2 that maximum protease activity was in medium containing 2.5 % sunflower oil seed waste, and the protease production decreased as the concentration of sunflower oil seed waste increased 2.5–3.0 %.

Purification of proteases

An effective scheme for protease purification was developed combining cold acetone precipitation and DEAE-cellulose ion exchange chromatography. The protease was precipitated from the cell-free medium optimally at 60 % cold acetone concentration and applied to the DEAE-cellulose column. There are many proteins eluted from 0.1 M NaCl to 0.5 M NaCl concentration as shown in the chromatogram, but only two peaks showed protease activity (P1 and P2), as shown in Fig. 3a. The P1 was eluted at 0.1 M NaCl concentration, whereas P2 eluted at 0.2 M NaCl concentration. The molecular weights of P1 and P2 were found to be 25 kDa and 36 kDa, respectively, on the SDS-PAGE, as shown in Fig. 3b, which is comparable to those reported from other microorganisms such as 45 kDa from Bacillus subtilis megatherium (Gerze et al. 2005) and 28 kDa from Bacillus sp. B16 (Qiuhong et al. 2006).

a Purification profile of P1 and P2 protease of O. xanthineolytica NCIM 2839. The proteases were purified using DEAE-Cellulose ion exchange column chromatography, fractions collected (filled square) and protease activity (filled triangle). b SDS-PAGE analysis of purified P1 and P2 proteases. Lane M is standard molecular weight marker proteins, Lane P1 DEAE-Cellulose chromatography fraction of P1 protease, and Lane P2 DEAE-Cellulose chromatography fraction of P2 protease

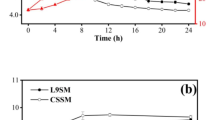

Effect of pH and temperature on enzyme activity

Although the enzymes were active at broad range of pH, 4.0–9.0, optimum activity was observed at pH 7.0 and pH 7.5 of P1 and P2 enzyme, respectively, as shown in Fig. 4a. P1 and P2 enzymes were retaining their 50 % activity between pH 5.5 and 8.0; this indicates that the enzyme was neutrophilic in nature. Saeki et al. (1994) reported alkaline protease from O. xanthineolytica strain TK-1 which is optimally active at pH 9.5–11.0 at 50 °C. It was observed that the optimal temperature for enzyme activity was 35 and 40 °C of P1 and P2 enzyme, respectively, as shown in Fig. 4b, where both the enzymes retained their 50 % activity between temperature 30 and 50 °C. The P1 enzyme was found to be more stable than the P2 enzyme, as shown in Fig. 4b.

a Effect of pH on purified P1 and P2 proteases. Residual activity of purified P1 protease (filled square) and of purified P2 protease (filled triangle) at various pH. b Effect of temperature on purified P1 and P2 proteases and its stability. Residual activity of purified P1 protease (filled square) and of purified P2 protease (filled triangle) at various temperatures and stability of P1 (multiple symbol) and P2 (open circle)

Effect of metal ions on enzyme activity

The effect of metal ions on P1 and P2 proteases is summarized in Table 2. Mn2+ was found to be an activator of P1 and P2, whereas Mg2+ activates only P1. Enzyme activity was completely inhibited in the presence of Hg2+. Cu2+ was found to be an inhibitor of P2 and slightly inhibitory for P2, whereas no effect was observed in the presence of Fe3+ ions.

Analysis of hydrolyzed products

After casein was hydrolysed by P1 and P2 separately, the products were analyzed by HPLC as shown in Fig. 5. It was observed that P1 hydrolyses casein into oligopeptides (Fig. 5, P1H), whereas P2 hydrolyses into amino acids (Fig. 5, P2H). This indicates that O. xanthineolytica NCIM 2839 produces a protease system which has two components, i.e., P1 and P2, the P1 has endoprotease activity and P2 has exoprotease activity.

HPLC analysis of hydrolysed products of P1 and P2 proteases of O. xanthineolytica NCIM 2839. The purified protease P1 and P2 was incubated with casein at 30 °C for 10 min and hydrolyzed products were detected by HPLC. PSC substrate control, P1H products formed after action of P1 enzyme and P2H products formed after action of P2 enzyme

Treatment of soymilk with immobilized protease

Protease immobilized by the Ca-alginate method was found to be more stable than the free enzyme. The earlier reports suggest that the protease can be immobilized using agar, sodium alginate, polyacrylamide and gelatin, but more leakage was observed with agar and less with gelatin (Kumar and Vats 2010). So Ca-alginate method could be preferable for immobilization of protease. After treatment of the soymilk using immobilized proteases, it was observed that the beany flavor of the soymilk was reduced and gives the pleasant smell which makes soymilk more acceptable for consumers. For a long time, it was known to human that amino acids which are produced by the action of protease give flavor to the product. It was also found that treated milk using immobilized proteases showed increased shelf life at 4 °C up to 15 days than the control which was up to 10 days. The shelf life could be increased because of antimicrobial peptides produced by the action of proteases of O. xanthineolytica NCIM 2839. Several reports on enzymatic hydrolysis of soy protein have promoted numerous bioactive functions, such as angiotensin-I converting enzyme inhibitory activity (Chiang et al. 2006), adipogenesis inhibitory activity (Tsou et al. 2010a, b), cholesterol-lowering activity (Tsou et al. 2009) and anti-oxidative activity (Moure et al. 2006).

Conclusion

In the present study, the low-cost production of protease from O. xanthineolytica NCIM 2839 using sunflower oil seed waste was carried out. As far as we are concerned, our work is the first contribution toward the production of protease using sunflower oil seed waste from O. xanthineolytica NCIM 2839. After the treatment of soy milk with protease, increased shelf life of soy milk encourages possible application of protease for the food industries.

References

Ates S, Mehmetoglu U (1997) A new method for immobilization of ß-galactosidase and its utilization in a plug flow reactor. Process Biochem 32:433–439

Chiang WD, Tsou MJ, Tsai ZY, Tsai TC (2006) Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitor derived from soy protein hydrolysate and produced by using membrane reactor. Food Chem 98:725–732

De Azeredo LAI, De Lima MB, Coelho RRR, Freire DMG (2006) A low-cost fermentation medium for thermophilic protease production by Streptomyces sp. 594 using feather meal and corn steep liquor. Curr Microbiol 53:335–339

Drucker H (1972) Regulation of exocellular proteases in Neurospora crassa: induction and repression of enzyme synthesis. J Bacteriol 110:1041–1049

Egan H, Kirk RS, Sawyer R (1981) Pearsons chemical analysis of food, 8th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Frankena J, Koningstein GM, van Verseveld HW, Stouthamer AH (1986) Effect of different limitations in chemostat cultures on growth and production of exocellular protease by Bacillus licheniformis. Appl Microb Biotechnol 24:106–112

Gatade AA, Ranveer RC, Sahoo AK (2009) Physiochemical and sensorial characteristics of chocolate prepared from soymilk. Adv J Food Sci Technol 1:1–5

Gerze A, Omay D, Guvenilir Y (2005) Partial purification and characterization of protease enzyme from Bacillus subtilis megatherium. Appl Biochem Biotech 121:335–345

Gessesse A, Gashe BA (1997) Production of alkaline protease by an alkaliphilic bacteria isolated from an alkaline soda lake. Biotechnol Lett 19:479–481

Godfrey TA, Reichelt J (1985) Industrial enzymology: the application of enzymes in industry. The Nature Press, London

Godfrey T, West S (1996) Introduction to industrial enzymology, In: Godfrey T, West S (eds) Industrial enzymology, 2nd edn. Macmillan, London, pp 1–8

Gupta R, Beg QK, Lorenz P (2002) Bacterial alkaline proteases: molecular approaches and industrial applications. Appl Microb Biotechnol 59:15–32

Johnvesly B, Manjunath BR, Naik GR (2002) Pigeon pea waste as novel, inexpensive, substrate for production of a thermostable alkaline protease from thermoalkalophilic Bacillus sp. JB-99. Biores Technol 82:61–64

Kumar CG, Takagi H (1999) Microbial alkaline proteases: from a bioindustrial viewpoint. Biotechnol Adv 17:561–594

Kumar R, Vats R (2010) Protease production by Bacillus subtilis immobilized on different matrices. NY Sci J 3:20–24

Laemmli UK (1970) Cleavage of structural protein during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685

Liang T, Lin J, Yen Y, Wang C, Wang S (2006) Purification and characterization of a protease extracellularly produced by Monascus purpureus CCRC31499 in a shrimp and crab shellpowder medium. Enzyme Microb Technol 38:74–80

Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ (1951) Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193:265–275

Maestri E, Marmiroli M, Marmiroli N (2016) Bioactive peptides in plant-derived foodstuffs. J Prot. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2016.03.048

Merril CR (1987) Detection of proteins separated by electrophoresis. Adv Electrophor 1:111–139

Mora L, Aristoy MC, Toldra F (2016) Bioactive peptides in foods. Enc Food Health 395–400

Moughan PJ, Rutherfurd-Markwick K (2013) Food bioactive proteins and peptides: antimicrobial, immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. Diet, immunity and inflammation. Woodhead Publishing Limited, Cambridge, pp 313–340

Moure A, Domínguez H, Parajó JC (2006) Antioxidant properties of ultrafiltration-recovered soy protein fractions from industrial effluents and their hydrolysates. Process Biochem 40:447–456

North MJ (1982) Comparative biochemistry of the proteinases of eukaryotic microorganisms. Microbiol Rev 46:308–340

Qiuhong N, Xiaowei H, Baoyu T, Jinkui Y, Jiang L, Lin Z, Keqin Z (2006) Bacillus sp. B16 kills nematodes with a serine protease identified as a pathogenic factor. Appl Microb Biotechnol 69:722–730

Rao MB, Tanksale AM, Ghatge MS, Deshpande VV (1998) Molecular and biotechnological aspects of microbial proteases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62:597–635

Saeki K, Iwata J, Watanabe Y, Tamai Y (1994) Purification and characterization of an alkaline protease from Oerskovia xanthineolytica Tk-1. J Ferment Bioeng 77:554–556

Spinosa MR, Braccinia T, Ricca E, De Felice M, Morellic L, Pozzia G (2000) On the fate of ingested Bacillus spores. Res Microbiol 151:361–368

Tsou MJ, Kao FJ, Hhuang JB, Chiang WD (2009) Limited enzymatic hydrolysis of soy protein enhances cholesterol absorption inhibition in Caco-2 cells. Taiwanese J Agric Chem Food Sci 47:1–8

Tsou MJ, Kao FJ, Tseng CK, Chiang WD (2010a) Enhancing the antiadipogenic activity of soy protein by limited hydrolysis with flavourzyme and ultrafiltration. Food Chem 122:243–248

Tsou MJ, Lin WT, Tsui YL, Chiang WD (2010b) The effect of limited hydrolysis with neutrase and ultrafiltration on the anti-adipogenic activity of soy protein. Process Biochem 45:217–222

Van Tilburg R, Hounink EH, Vander MRR (1984) Innovation in Biotechnology. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 31–51

Waghmare SR, Ghosh JS (2010) Study of thermostable chitinases from Oerskovia xanthineolytica NCIM 2839. Appl Microb Biotechnol 86:1849–1856

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahoo, A.K., Gaikwad, V.S., Ranveer, R.C. et al. Improvement of shelf life of soymilk using immobilized protease of Oerskovia xanthineolytica NCIM 2839. 3 Biotech 6, 161 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0479-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0479-6