Abstract

Introduction

Asexuality is typically defined as a lack of sexual attraction, and yet this definition fails to include the multitude of experiences within the ace community. We explored the correlates of different cognitions, feelings, and desires reported by ace individuals.

Methods

Data for a cross-sectional study with 456 individuals from online ace communities (61.8% women; Mage = 24.62, SD = 6.98) were collected in 2019.

Results

Higher scores on the Asexuality Identification Scale (AIS) were associated with fewer experiences with romantic partners, more experiences with intimate affective relationships, and higher avoidant attachment. In contrast, sexual and romantic attractions were associated with more experiences with romantic partners. However, sexual attraction was associated with fewer experiences with non-sexual romantic relationships and lower AIS scores, whereas romantic attraction was associated with lower avoidant attachment and higher anxious attachment. The desire to have physically intimate romantic relationships was associated with more experiences with romantic partners, lower avoidant attachment, higher anxious attachment, and lower AIS scores. Lastly, the desire to have intimate affective relationships was associated with more experiences with solely affective relationships and higher anxiety attachment.

Conclusions

These findings show the importance of past experiences and individual differences in shaping the way ace individuals construe their identity, and experience feelings and desires.

Policy Implications

By highlighting the need to acknowledge diversity within the ace community, this study offers insights into how to increase awareness and develop more inclusive social policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Asexuality is often construed as a sexual identity and a distinct sexual orientation (Brotto & Milani, 2022; Guz et al., 2022). Researchers use the term “asexual” when referring to sexual identity, whereas the term “ace” or “a-spec” (asexuality spectrum) has been used by some members of the community as a more inclusive alternative to encompass the multiple experiences held by individuals. Here we use “ace” as an umbrella term to reflect such diversity. This sexual identity has gained visibility and recognition in the past years through the work of activists and spokespersons, and the creation of ace communities worldwide. For example, the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN), an online community created in 2001, has worked to increase awareness and acceptance of ace individuals. Yet, the reach of this work is restricted to individuals who have access to the internet, understand English, and actively search for asexuality-related information.

There is a generalized lack of representation of ace individuals in research (e.g., Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012), arguably because researchers tend to overlook this sexual identity in their surveys (Rothblum et al., 2020) or fail to include “ace” and its multiple labels as explicit sexual identity categories (e.g., Fausto-Sterling, 2019; Herek et al., 2010). This omission could have led to misclassifications or underrepresentation of ace individuals in research, forcing them to choose other identity labels. A growing interest in the experiences of ace individuals has been observed in the recent years among academics and professionals. For example, researchers have collected data with ace individuals from different countries across the world, including New Zealand (Greaves et al., 2017), Finland (Höglund et al., 2014), and China (Zheng & Su, 2018). Still, it remains among the least studied and understood sexual minority identities (Cranney, 2016; Van Houdenhove et al., 2014). Hence, researchers must work to have a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted and complex ace identity as well as its correlates.

Ace Identity

Researchers tend to use a sexual lens to explore an ace identity, which is typically equated to asexuality and defined as the absence of sexual attraction to others (Bogaert, 2006; Brotto et al., 2010). Indeed, sexual desire, sexual functioning, and sex disgust are often used as premises in this field to illustrate the experiences of ace individuals (Bogaert, 2004; Brotto & Yule, 2011, 2017; Brotto et al., 2010; Yule et al., 2015; Zheng & Su, 2018). However, this approach fails to capture the diversity of personal and interpersonal experiences on the ace spectrum (Cerankowski & Milks, 2010). As such, some researchers have questioned the boundaries of the typical definition of asexuality (Chasin, 2011) and argued that sexuality is just one dimension of the complex ace identity (Cranney, 2016). For example, some individuals in the ace community consider that sexual and romantic attraction are separate and independent feelings (i.e., split attraction model), whereas others argue that such categorization fails to be inclusive (for discussions, see Ask-an-Aro, 2019; Sennkestra, 2020; Siggy, 2019). Indeed, we need to acknowledge recent discussions arguing asexuality as distinct from other sexual orientations (e.g., Brotto & Milani, 2022), while at the same time acknowledging differences between sexual and romantic identities. For example, ace individuals can experience little to no sexual attraction (i.e., asexual), experience sexual attraction after forming deep emotional connections (i.e., demisexual), or experience fluctuating levels of sexual attraction (i.e., graysexual; Copulsky & Hammack, 2023; Glatzer, 2021; Hille et al., 2020). Likewise, some ace individuals can feel little to no romantic attraction (i.e., aromantic), whereas others can experience these feelings (i.e., romantic; Carvalho & Rodrigues, 2022). These differences and nuances are related to distinct perceptions, feelings, and experiences within the ace community (e.g., how ace individuals construe and navigate social and affective relationships).

As an intrapersonally evolving sexual identity, ace individuals make sense of their self-exploration and experiences by having a common language and jointly creating new terms with other members of the community. Ace individuals gradually understand their sexual identity as they gain deeper insights into themselves and their experiences (Foster et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2017; MacNeela & Murphy, 2015). This is particularly relevant because an ace identity is not widely shared as a social construct (i.e., there is a generalized lack of knowledge about asexuality from the public; Robbins et al., 2016) and is lesser known than other sexual minorities (Decker, 2015; Hayfield, 2020). Therefore, individuals tend to rely on their community as a useful source of information and discovery (Kelleher & Murphy, 2022). Informed by research on the development of other sexual identity minorities and on the development of an ace identity, we believe that the development of an ace identity is a dynamic process. Hence, a more comprehensive understanding must consider the multiple experiences of ace individuals, including (but not limited to) the distinction between sexual and romantic attractions, and how these experiences are shaped by past relations and individual differences.

Ace Identity Development

Research conceives the development of sexual identities as a dynamic process that continuously changes and can be revisited as individuals explore and experience their sexuality (e.g., Horowitz & Newcomb, 2001; Rosario et al., 2006). For example, individuals from sexual minorities (but not exclusively) can experience changes in their sexual identity over time, as a result of an identity formation process that occurs on a continuum marked by experimentation (Van de Meerendonk & Probst, 2004). Ace individuals negotiate sexual assumptions, desires, intimacy expectations, and other normative scripts with themselves and others (Carrigan, 2011; Dawson et al., 2019; Mitchell & Hunnicutt, 2019; Scherrer, 2008). Yet, only a handful of studies aimed to gain insights into the development of an ace identity by asking individuals to think about their past and current personal and interpersonal experiences. Among other topics, researchers have focused on how ace individuals explored their identity (Van Houdenhove et al., 2015), managed their identity (MacNeela & Murphy, 2015), and experienced their coming out (Robbins et al., 2016). Broadly, these studies have shown that ace individuals question their feelings and relational motives (often distinct from those expressed and enacted by their peers), search for more information about their feelings and motives (e.g., in online groups and communities), go through the process of accepting their identity (sometimes marked by social resistance and denial), and come to terms with an ace identity (e.g., feeling comfortable and disclosing their identity to others). For example, Mitchell and Hunnicutt (2019) found that some ace individuals start by identifying as demisexual before having more knowledge about the ace spectrum and recognizing that being asexual has a better fit to their identity. Individuals in this study described a fluid and nuanced unfolding of an ace identity that involved searching online for information and connecting with ace communities to discuss their beliefs, attitudes toward sex, attraction desires, and romantic orientations. Likewise, Cranney (2016) found that sexual attraction fluctuated among young adults who indicated not experiencing sexual attraction. Specifically, the author found that most individuals who were not sexually attracted to others experienced changes in sexual attraction later on, with only a few individuals maintaining their lack of sexual attraction over time. To some extent, then, this research echoes the concept of sexual fluidity, conceived as a predisposition to experience transient or stable changes in sexual attractions, identities, and/or behaviors (Diamond, 2016).

Taken together, these studies defy the assumption that lacking sexual attraction is a temporally stable and shared attribute across the ace spectrum, and add to the discussion that relationships often contribute to individuals exploring their sexuality and developing an ace identity. However, the way ace individuals construe and experience intimacy, and how this connects to an ace identity, have remained largely understudied (Scott & Dawson, 2015). One exception is the relational approach proposed by Dawson et al. (2019), which conceptualizes the development of an ace identity as a process resulting from (and shaped by) social interactions and the negotiation of intimate practices in relationships. Intrinsically related to these negotiations are individual views about sexual activity and past experiences with intimate relationships.

Sexual Behavior and Intimate Relationships

Ace individuals have romantic relationships with both ace and allosexual partners (i.e., those who identify as sexual; e.g., Antonsen et al., 2020). When compared with demisexual or graysexual individuals, those who identify as asexual are more likely to be single and less likely to engage in sexual behaviors (Hille et al., 2020). The assumption that ace individuals have an overall negative attitude toward sexual behaviors has been supported by research (Bulmer & Izuma, 2018; Clark & Zimmerman, 2022; Dawson et al., 2019). Nonetheless, some ace individuals engage in solitary sexual activities (e.g., masturbation; Yule et al., 2014, 2017), and others consider having partnered sex (Decker, 2015). Indeed, even though most ace individuals report sex aversion, are unwilling to have sex, or are even disgusted by sex (Van Houdenhove et al., 2015), others are neutral or indifferent when it comes to sexual activity, and others still have favorable attitudes and construe sexual activity as a healthy practice (Carrigan, 2011). These latter individuals are more likely to have romantic relationships with an allosexual partner and consider engaging in sexual activity to satisfy the desires of their partner (Antonsen et al., 2020; Brotto et al., 2010; Dawson et al., 2016; Prause & Graham, 2007; Van Houdenhove et al., 2015). This clearly shows that diverse motives and experiences with sexuality must be acknowledged for a more accurate understanding of an ace identity.

Differences in attitudes toward sex may also be related to (a)romantic orientations. In their study, Carvalho and Rodrigues (2022) explored personal and interpersonal differences depending on whether ace individuals experience romantic attraction or not. The authors found that romantic ace individuals reported less sex aversion, more sexual and romantic experiences, more sexual partners, and a stronger desire for romantic relationships (either with or without sexual intimacy), when compared with aromantic ace individuals. Note that having an aromantic orientation does not necessarily equate to lacking or avoiding interpersonal intimacy. Indeed, aromantic ace individuals develop meaningful and intimate connections void of romantic feelings (e.g., intimate friendships; Mitchell & Hunnicutt, 2019; Scott & Dawson, 2015). Adding to their experiences with sexuality and relationships, the experiences that ace individuals have with significant others might also contribute to how they identify and relate to others.

Attachment

Research has been using attachment theory as a framework to understand social identity development, conceptualizing it as a construction that arises from the assimilation and integration of experiences in the context of evolving relationships (Kerpelman & Pittman, 2018). This theory postulates that experiences with significant individuals throughout the lifespan (particularly in infancy) contribute to relatively stable internal dynamic models that shape future relationships (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Research has consistently shown that attachment styles are related to motives, feelings, and behavior in romantic relationships (Shaver et al., 2005). In contrast to securely attached individuals, those with an avoidant attachment tend to be emotionally distant from their partners, avoid closeness, and fear intimacy, whereas those with an anxious attachment tend to seek care and attention, fear abandonment, and worry about rejection (Brennan et al., 1998; Simpson & Rholes, 2017). Consequently, both avoidant and anxious individuals tend to adopt defensive strategies in their interactions with romantic partners (Fraley & Shaver, 2000; Mikulincer et al., 2003).

The role of attachment on sexual desire and sexual functioning has been widely discussed (for a review, see Birnbaum & Reis, 2019). Overall, individuals with an avoidant attachment tend to report less dyadic sexual desire (Attaky et al., 2022), experience discomfort with or avoid sexual activity (Tracy et al., 2003), report lower emotional intimacy when having sex (Gentzler & Kerns, 2004), and are less sexually satisfied (Lafortune et al., 2022). Individuals with an anxious attachment tend to report more sexual desire (Mark et al., 2018), have more casual sexual partners (and fewer committed sexual partners; Busby et al., 2020), and tend to engage in sexual activity to increase relationship intimacy (Davis et al., 2004; Impett et al., 2008). Extending this reasoning to ace individuals, Brotto and colleagues (2010) suggested that having an ace identity could be related to having an avoidant attachment style, given their predominant low sexual desire. This hypothesis received some empirical support in the study by Carvalho and Rodrigues (2022), who found that aromantic ace individuals scored higher in avoidant attachment when compared to romantic ace individuals. No differences between both groups of ace individuals emerged for anxious attachment scores. Hence, attachment theory assumptions might be helpful to understand how ace individuals perceive themselves and relate to others.

Current Study and Hypotheses

Our goal was to explore the correlates of feelings of sexual and romantic attraction, as well as desires to have intimate relationships in the future, among ace individuals. More specifically, we explored whether feelings and desires were associated with past experiences with romantic partners (distinguishing between ace and allosexual partners), non-sexual intimate relationships (distinguishing between romantic and solely affective relationships), insecure attachment styles (distinguishing between avoidance or anxious), and asexuality identification.

Similar to individuals from other sexual minorities, past experiences of ace individuals—whether questioning social scripts or experimenting with relationships and sexuality—may shape the way these individuals construct their own identity. Indeed, some authors have argued that the development of an ace identity is a dynamic process shaped by personal factors and interpersonal experiences and relationships (MacNeela & Murphy, 2015; Mitchell & Hunnicutt, 2019; Scott & Dawson, 2015). However, having an ace identity is often equated to asexuality and is typically defined as a lack of sexual attraction or sexual behavior that is relatively stable over time (Bogaert, 2004). To better understand the correlates of having an ace identity, we used scores on the Asexuality Identification Scale (AIS; Yule et al., 2015). This measure was originally developed to categorize individuals as asexual (i.e., individuals who lack sexual attraction), regardless of whether or not they identify as such. Research has already shown that ace individuals with higher AIS scores are more likely to identify as aromantic, tend to have less experience with sexual and romantic relationships, and score higher in avoidance attachment (Carvalho & Rodrigues, 2022). Replicating and extending these findings, we expected ace individuals with higher scores on the AIS to also report having less experience with romantic partners (H1a) and less experience with intimate relationships (H1b), and score higher in avoidant attachment (H1c).

We also expected ace individuals who feel more sexual and romantic attraction to report having more experience with romantic partners (H2a) and more experience with intimate relationships (H2b), score lower in avoidant attachment (H2c), and score lower on the AIS (H2d). Likewise, ace individuals with a stronger desire to have physically intimate romantic relationships were expected to report having more experience with romantic partners (H3a) and more experience with intimate relationships (H3b), score lower in avoidant attachment (H3c), and score lower on the AIS (H3d). Lastly, we expected ace individuals with a stronger desire to have solely affective intimate relationships (e.g., intimate friendships) to report having less experience with romantic partners (H4a) and more experience with intimate relationships (H4b), score lower in avoidant attachment (H4c), and score higher on the AIS (H4d). Given the lack of studies examining the role of anxious attachment in the experiences of ace individuals, we did not offer a priori hypotheses.

Method

Participants

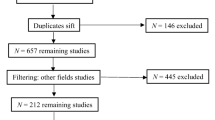

Of the 714 individuals who started the online survey, 256 did not complete the survey and were removed from the analyses. The final sample included 456 individuals from different online ace communities. As shown in Table 1, participants were, on average, 25 years old (M = 24.62, SD = 6.98), and most identified as cisgender (69.3%), women (61.8%), and asexual (76.8%). Also, most participants lived in the USA (54.8%), resided in urban areas (77.2%), were attending college (35.7%), had a bachelor’s degree (28.1%), and were not romantically involved (82.5%).

Measures

Identification with Asexuality

We used the AIS (Yule et al., 2015) and asked participants to “keep in mind a definition of sex or sexual activity that may include intercourse/penetration, caressing, and/or foreplay” when answering the scale. This scale uses mostly sex-based items, including sexual attraction (e.g., “I experience sexual attraction towards other people” [reverse-scored]) and lack of interest in sex (e.g., “I would be content if I never had sex again”), but also asexual identity (e.g., “The term “nonsexual” would be an accurate description of my sexuality”). Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with 12 items on a 7-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree). Items were mean aggregated (α = .84), with higher scores indicating a stronger identification with asexuality.

Sexual and Romantic Attraction

We asked participants to indicate the extent to which they currently experience sexual attraction (“To what extent do you feel sexual attraction for other people, i.e., desire for a sexual relationship or sexual contact with someone?”) and romantic attraction (“To what extent do you feel romantic attraction for other people, i.e., an emotionally intimate connection with someone, not related to sex?”). Responses to each item were given on a 7-point scale (1 = Not at all to 7 = Very much). Items were treated separately in our analyses.

Desire to Have Intimate Relationships

Participants were asked to indicate their desire (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree) to have physically intimate romantic relationships using two items: “To what extent would you like to be in a significant romantic relationship with physical intimacy, including sex?” and “To what extent would you like to be in a significant romantic relationship with physical intimacy, but excluding sex?” Responses were mean aggregated, r(456) = .25, p < .001, with higher scores indicating a stronger desire to have physically intimate romantic relationships. We also asked participants their desire (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree) to have solely affective intimate relationships without sexual activity using two items: “To what extent would you like to be in a non-romantic relationship with physical intimacy but excluding sex?” and “To what extent would you like to be in a significant non-romantic relationship without physical intimacy (friendship-like)?” Responses were also mean aggregated, r(456) = .30, p < .001, with higher scores indicating a stronger desire to have solely affective intimate relationships.

Past Romantic Partners

Participants were asked to indicate if they had experiences with asexual (“Have you ever had romantic partners who were asexual?”) and allosexual (“Have you ever had romantic partners who were not asexual?”) romantic partners. Responses to each item were given on a 7-point scale (1 = Never to 7 = Always). Items were treated separately in our analyses.

Past Intimate Relationships

We asked participants to indicate if they ever had non-sexual romantic relationships (“Have you ever had a significant relationship that can be considered romantic, i.e., a close and intimate non-sexual relationship based exclusively on affection [e.g., holding hands, kissing, etc.]?”) and solely affective intimate relationships (“Have you ever had a significant relationship that can be considered non-romantic, i.e., a close and intimate non-sexual relationship, in which affective gestures [e.g., holding hands, kissing, etc.] were rarely expressed?”). Responses to each item were given on a 7-point scale (1 = Never to 7 = Always). Items were treated separately in our analyses.

Attachment Style

We used the Adult Attachment Questionnaire (Rholes, 1996) to assess avoidant attachment style (eight items; e.g., “I’m not very comfortable having to depend on other people”) and anxious attachment style (nine items; e.g., “I usually want more closeness and intimacy than others do”). Responses to each item were given on 7-point scale (1 = Completely disagree to 7 = Completely agree). Items on each subscale were mean aggregated, with higher scores indicating a more avoidant attachment (α = .79) and a more anxious attachment (α = .77).

Procedure

This study followed the guidelines issued by the Ethics Council of Iscte-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa. We recruited participants from social networking groups and Reddit discussion boards (e.g., r/Asexuality) used by the ace community, between July and August 2019. Permission to post any study advertisements was requested beforehand from administrators or moderators. Individuals were invited to take part in an anonymous online survey about asexuality and ace individuals. To participate, individuals had to be at least 18 years old, have an ace/asexual identity, and be part of an ace community. After accessing the provided weblink, participants were informed about their rights as participants and asked to give their consent before proceeding with the study. There was no compensation involved for participating in the survey. The survey started with sociodemographic questions (e.g., age, sex assigned at birth, gender identity), followed by the remaining measures. In the end, participants were thanked and debriefed. Data were collected on Qualtrics, and participants took, on average, 16 min to complete the survey.

Analytic Plan

We first examined the overall pattern of correlations between variables. To have an overview of the experiences reported by our participants, we computed one-sample or pairwise comparisons using t-tests. We tested our hypotheses by computing five hierarchical linear regressions to examine the correlates of AIS scores (model 1), sexual attraction (model 2), romantic attraction (model 3), desire for physically intimate romantic relationships (model 4), and desire for solely affective intimate relationships (model 5). In model 1, predictor variables were past experiences with asexual and allosexual romantic partners, past experiences with non-sexual romantic relationships and solely affective intimate relationships (step 1), and anxious and avoidant attachment scores (step 2). In all other models, predictor variables were the same in both steps, and we added AIS scores as a predictor variable (step 3).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Overall descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 2. As shown in Fig. 1, AIS scores were significantly above the mid-point of the response scale, t(455) = 33.79, p < .001, d = 1.58, participants reported experiencing more romantic (vs. sexual) attraction, t(454) = 30.32, p < .001, d = 1.42, reported a stronger desire to have solely affective intimate relationships (vs. physically intimate romantic relationships), t(455) = 8.13, p < .001, d = 0.38, were more likely to have had allosexual (vs. asexual) romantic partners, t(453) = 17.97, p < .001, d = 0.84, and were more likely to have had non-sexual romantic relationships (vs. solely affective intimate relationships), t(455) = 2.89, p = .004, d = 0.14. Lastly, participants scored higher on avoidant (vs. anxious) attachment style, t(455) = 6.34, p < .001, d = 0.30.

Main Analyses Footnote 1

AIS Scores

As shown in Table 3, participants who scored higher on the AIS had less experience with asexual, p = .008, and allosexual romantic partners, p = .008, more experience with solely affective intimate relationships, p < .001, and scored higher on avoidant attachment, p = .010.

Sexual and Romantic Attraction

The results are summarized in Table 4. Participants who reported more sexual attraction feelings had more experience with asexual, p = .004, and allosexual romantic partners, p < .001, had less experience with non-sexual romantic relationships, p = .045, and scored lower on the AIS, p < .001. Participants who reported more romantic attraction also had more experience with asexual, p < .001, and allosexual romantic partners, p < .001, and scored lower on avoidant attachment, p < .001, and higher on anxious attachment, p < .001.

Desire for Intimate Relationships

As shown in Table 5, participants with a stronger desire to have physically intimate romantic relationships had more experience with asexual, p = .002, and allosexual romantic partners, p < .001, scored lower on avoidant attachment, p < .001, and higher on anxious attachment, p < .001, and scored lower on the AIS, p < .001. Participants with a stronger desire to have solely affective intimate relationships had more experience with solely affective intimate relationships, p < .001, and scored higher on anxious attachment, p < .001.

Discussion

Research must go beyond the mere absence of sexual attraction when studying an ace identity, as the diversity of feelings and experiences within the ace community is often concealed by this operationalization. As suggested by recent research, ace individuals need to navigate and negotiate the expectations and demands of others while striving to achieve the forms of intimacy they desire (e.g., Dawson et al., 2016; Mitchell & Hunnicutt, 2019). We built upon this reasoning and hypothesized that affective experiences, interpersonal relationships, sexual experiences, and attachment styles could also be relevant to their identity.

Overall, we found mixed support for our hypotheses. As expected, participants who had fewer experiences with asexual and allosexual romantic partners (H1a) scored higher on the AIS. Also, as expected, having had more experience with asexual and allosexual romantic partners (H2a) and scoring lower in the AIS (H2d) were associated with feelings of romantic and sexual attraction. Likewise, having had more experiences with asexual and allosexual romantic partners (H3a) and scoring lower in the AIS (H3d) were associated with a stronger desire to have physically intimate romantic relationships. Lastly, having had more experiences with solely affective intimate relationships (H4b) was associated with a stronger desire to have this type of relationship. These findings clearly show the variability of experiences within the ace community and highlight the extent to which different understandings of an ace identity (even within the same community) are related to differences in sexual desire, romantic intentions, and intimacy. As such, these findings contribute to current discussions around the distinction, or lack thereof, between sexual and romantic attraction. Equally important, these findings extend past research (e.g., Diamond, 2016; Mitchell & Hunnicutt, 2019) and suggest that experimenting with sexuality and relationships (either with asexual or allosexual partners), and perceiving sexual activity more favorably (i.e., seeing sex as a healthy practice), can contribute to a more fluid ace identity. This also resonates with recent longitudinal evidence indicating that ace individuals who report more dyadic sexual desire and sexual attraction, and who are less likely to identify as asexual, have a more fluid sexual identity (Su & Zheng, 2023). In other words, ace individuals may have to engage in different experiences to realize their ideal forms of intimacy (Dawson et al., 2019).

Against our original predictions, having had more experiences with solely affective intimate relationships was associated with higher AIS scores (H1b), and having had fewer experiences with non-sexual romantic relationships was associated with more feelings of romantic attraction (H2b). Some of these results were not necessarily surprising and suggest that ace individuals may be comfortable establishing non-sexual and non-romantic relationships and still perceive those experiences to be congruent with their identity. Other results may be explained by the fluidity underlying the development of an ace identity (Mitchell & Hunnicutt, 2019). For example, ace individuals with restricted sexual and relational experiences may be less likely to question their identity, and therefore behave in accordance with their beliefs and feelings. Converging with the findings of Dawson and colleagues (2016), some ace individuals may need to experiment with relationships to realize and accept their lack of sexual attraction, whereas other individuals are still exploring their desires but at the same time struggle to form relationships. In this latter case, ace individuals may be afraid to disclose their questioning identity to potential partners, which can prevent them from establishing certain relationships.

We also found support for the role of attachment styles on the experiences and desires of ace individuals (Brotto et al., 2010). As expected, avoidant attachment scores were associated with higher AIS scores (H1d), having fewer romantic attraction feelings (H2d), and desiring physically intimate romantic relationships to a lesser extent (H3d). These findings are consistent with recent research showing that ace individuals with fewer romantic feelings (i.e., aromantic ace individuals) scored higher on avoidant attachment and reported stronger identification with asexuality (Carvalho & Rodrigues, 2022). Hence, having an avoidant attachment may create a conflict between an ace identity and romantic attraction feelings, and lead some individuals to fear intimacy, avoid closeness, and keep an emotional distance from their partners. Even though we had no a priori hypotheses, we also found that having an anxious attachment was positively associated with romantic attraction feelings and the desire for intimate relationships—either physically intimate romantic relationships or solely affective intimate relationships. By having an anxious attachment, ace individuals may experience romantic attraction and consider the possibility of having intimate relationships in the future, but at the same time may be anxious around potential intimate partners, possibly due to fear of being rejected or uncertainty regarding relational and sexual expectations and norms.

Overall, our results showed that AIS scores uniquely contributed to feelings of sexual attraction and desire for intimate romantic relationships (both negatively), but not to feelings of romantic attraction or the desire to have solely affective intimate relationships. Individuals categorized as asexual using the AIS tend to lack sexual desire and perceive sex as physically aversive (Yule et al., 2015). However, even though individuals with higher AIS scores are likely to avoid having romantic partners and romantic relationships (Carvalho & Rodrigues, 2022), this does not seem to extend to relational experiences that are not necessarily bound to sexuality or sexual activity. Hence, using the AIS without a broader understanding of past experiences and individual differences can lead to a biased understanding of the feelings and desires of ace individuals.

Limitations and Future Studies

Our findings must be taken with caution in light of some limitations. Our cross-sectional data prevents us from establishing causality, and we did not control for secure attachment styles in our analyses. This can increase the risk of pathologizing ace identities by leading to a stigmatizing view of ace individuals (e.g., assuming that ace individuals tend to have an avoidant attachment to others) and potentially biasing our understanding of the role of attachment styles during the process of developing and accepting an ace identity. Future studies could expand our current findings by examining the implications of attachment styles for the individual and relational well-being of ace individuals. For example, a longitudinal approach with ace individuals would help understand processes such as identity exploration and the construction of relational expectations and concerns, determine which and how attachment styles facilitate or inhibit the initiation and maintenance of different types of relationships (e.g., non-romantic intimate relationships; romantic relationships), and examine factors that contribute to the development of resilience against personal adversities (e.g., experienced social stigma).

We were also unable to determine how the type and quality of past experiences with romantic partners or intimate relationships (e.g., romantic relationships vs. intimate friendships) shaped the ace identity development process. Arguably, ace individuals who had negative experiences in the past may have a different understanding of their identity when compared to ace individuals who had positive experiences. Relatedly, we did not assess for how long participants identified as ace, the self-acceptance of their identity, or their past experiences with social stigma. For instance, some of our participants might have their identities more stable, whereas others might be still exploring their identities. Informed by sexual orientation research (e.g., Mustanski et al., 2014; Rosario et al., 2006), future studies could address the stability of different components of an ace identity from a longer life course perspective. For instance, researchers could examine in greater detail the different stages of developing an ace identity, if, how, and under which conditions motivations to have (or not) different types of intimate relationships vary according to each stage, and the role of individual differences (e.g., attachment style) in these processes. These studies could also take a step further and examine the implications of having an ace identity for personal satisfaction and well-being, and how intimate relationships (whether physically intimate or solely affective) can help ace individuals fulfill their needs for affection.

We recruited a diverse sample of individuals from ace communities around the world, but our sample was biased by including more women and cisgender individuals. We also failed to account for possible cultural differences (e.g., individuals from more accepting cultural contexts may have more access to information and feel safer discussing their ace identity with others). Moreover, our sample included individuals motivated to search for information and access online resources, who were likely to participate in discussions surrounding the multiple experiences of ace individuals, have more knowledge about their own experiences, embrace specific language within the community, be more self-aware of their identity, and take their identity as a central part of themselves. This may be relevant when considering the generalization of our findings (e.g., past studies suggest a higher sexual fluidity among women; Diamond, 2016), particularly when it comes to individuals who struggle to access information, are questioning their identity, lack support from an ace community, or are unaware of the diversity within the ace spectrum.

Lastly, we only had a small subsample of participants who identified with labels other than “asexual” (e.g., graysexual, demisexual), which prevented us from conducting finer analyses considering the intersections between sexual orientation, sexual identity, and romantic orientation. For example, an ace individual can identify as demisexual and have a romantic orientation (Copulsky & Hammack, 2023). Future studies (and particularly those with representative samples) should seek to examine in detail the diverse experiences of ace individuals while accounting for the nuances and intersections between identities. Studies could also consider complementing quantitative analyses with qualitative methodologies to gain insights into the complexities surrounding the development of an ace identity (for example, see Kelleher & Murphy, 2022). We believe that using the AIS was not a limitation, nor did it go against our main argument, because we used the AIS scores as an indicator instead of using scores to categorize participants. Still, future studies should question the validity of this approach for identification purposes, as it may be reductive and fail to acknowledge the diverse lived experiences of ace individuals. Alternatively, future studies could consider revising the AIS and developing a more detailed instrument to properly assess such diversity.

Conclusion and Implications

This study explored a range of lived experiences of ace individuals, a sexual identity minority often overlooked in research and society. Taken together, our findings suggest that ace identity is a complex and multifaceted construct, filled with nuances and diverse lived experiences. We also extended the attachment framework to better understand the development of an ace identity. However, we have no empirical evidence suggesting that an ace identity is caused by certain childhood experiences. Making empirically unfounded assumptions is likely to have negative political and social ramifications, perpetuate harmful stereotypes, and stigmatize asexuality as a disorder. Despite the increasing awareness of the ace community, ace individuals are still underrepresented and misrepresented in society (Gupta & Cerankowski, 2017). This contributes to misconceptions about what it means to have an ace identity (including for people working in the healthcare system; Jones et al., 2017) and can facilitate externalized and internalized stigmatization (e.g., Mollet, 2021). For example, our results highlighted that sexual attraction and romantic attraction are distinct experiences (with different correlates) that sometimes can coexist (but not necessarily) within the ace community. Including our current findings in discussions about diversity in communities (both in person and online) would offer additional opportunities for the self-discovery and self-acceptance of individuals who are struggling with their ace identity. These discussions could also offer opportunities to improve societal knowledge about the ace community, promote accepting discourses from the media and the general public, and ultimately ensure fundamental rights of acceptance and equity for ace individuals.

Therapists might also benefit from having more knowledge about the diversity within the ace community, how past experiences and individual differences can contribute to the development of an ace identity (and in which direction), and the different processes that underlie its development. Along with existing results, our study contributes to preventing the risk of fitting ace individuals into the prototype of asexuality, disregarding their feelings and experiences, and perpetuating stigmatizing views of the ace community, even among mental health professionals. Moreover, by understanding the barriers and concerns related to the process of developing an ace identity, therapists are better equipped to help patients who are struggling with their sexual identity, some of whom may be unaware of specific ace terms or online ace communities. Based on our findings, therapists can make use of individual past experiences, create safer spaces to discuss sexual and relationship expectations and normative views, and work around issues related to internalized negativity. Likewise, our findings offer preliminary evidence on how attachment styles can facilitate (or prevent) ace individuals from exploring their identity and relationships. Based on these findings, therapists can develop tools to help individuals develop more secure attachment styles with others and have more positive experiences.

Our results can also inform the development of policies aimed at increasing awareness and promoting safer spaces for ace individuals. For example, policymakers working in healthcare can help create conditions for ace individuals to have better (and more adequate) social and psychological support, feel that their interpersonal and relationship needs are acknowledged and met (based on their past experiences), and consequently improve their psychological and physical well-being. For example, our results show that some ace individuals have sex, and therefore healthcare professionals should be prepared to discuss sexual health issues in their practice. Policymakers working with education can also use our findings to inform the development of accurate and comprehensive modules on asexuality and ace identities, most of which tend to be left out of current sexuality education curricula. By addressing the unique challenges faced by individuals during their identity development (e.g., what does it mean to have an ace identity), throughout their socialization (e.g., individuals in romantic relationships are expected to have sex), and during their interactions with others (e.g., different understandings of physical intimacy), sexuality educators can help foster positive discourse and accepting attitudes in younger generations. Lastly, policymakers working with human rights can advocate for the recognition of asexuality as a valid sexual identity and work to ensure that ace individuals are not discriminated against based on their identity.

Data Availability

All materials and anonymized data are available upon reasonable request from the first author.

Notes

Results from the hierarchical linear regressions were overall consistent after adding covariates to the analyses (i.e., age, country of residence, area of residence, education level, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual identity, and relationship status).

References

Antonsen, A. N., Zdaniuk, B., Yule, M., & Brotto, L. A. (2020). Ace and aro: Understanding differences in romantic attractions among persons identifying as asexual. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(5), 1615–1630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01600-1

Ask-an-Aro. (2019). The split attraction model: Pros and cons. Aromantic Ruminations. https://askanaro.wordpress.com/2019/01/20/

Attaky, A., Kok, G., & Dewitte, M. (2022). Attachment orientation moderates the sexual and relational implications of sexual desire discrepancies. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 48(4), 343–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2021.1991537

Birnbaum, G. E., & Reis, H. T. (2019). Evolved to be connected: The dynamics of attachment and sex over the course of romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.005

Bogaert, A. F. (2004). Asexuality: Prevalence and associated factors in a national probability sample. The Journal of Sex Research, 41(3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490409552235

Bogaert, A. F. (2006). Toward a conceptual understanding of asexuality. Review of General Psychology, 10(3), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.10.3.241

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). The Guilford Press.

Brotto, L. A., & Milani, S. (2022). Asexuality: When sexual attraction is lacking. In D. P. VanderLaan & W. I. Wong (Eds.), Gender and sexuality development: Contemporary theory and research (pp. 567–587). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84273-4_19

Brotto, L. A., & Yule, M. A. (2011). Physiological and subjective sexual arousal in self-identified asexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(4), 699–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9671-7

Brotto, L. A., & Yule, M. (2017). Asexuality: Sexual orientation, paraphilia, sexual dysfunction, or none of the above? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(3), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0802-7

Brotto, L. A., Knudson, G., Inskip, J., Rhodes, K., & Erskine, Y. (2010). Asexuality: A mixed-methods approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(3), 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9434-x

Bulmer, M., & Izuma, K. (2018). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward sex and romance in asexuals. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(8), 962–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1303438

Busby, D. M., Hanna-Walker, V., & Yorgason, J. B. (2020). A closer look at attachment, sexuality, and couple relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(4), 1362–1385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519896022

Carrigan, M. (2011). There’s more to life than sex? Difference and commonality within the asexual community. Sexualities, 14(4), 462–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460711406462

Carvalho, A. C., & Rodrigues, D. L. (2022). Sexuality, sexual behavior, and relationships of asexual individuals: Differences between aromantic and romantic orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(4), 2159–2168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02187-2

Cerankowski, K. J., & Milks, M. (2010). New orientations: Asexuality and its implications for theory and practice. Feminist Studies, 36(3), 650–664.

Chasin, C. D. (2011). Theoretical issues in the study of asexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(4), 713–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9757-x

Clark, A. N., & Zimmerman, C. (2022). Concordance between romantic orientations and sexual attitudes: Comparing allosexual and asexual adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(4), 2147–2157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02194-3

Copulsky, D., & Hammack, P. L. (2023). Asexuality, graysexuality, and demisexuality: Distinctions in desire, behavior, and identity. The Journal of Sex Research, 60(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.2012113

Cranney, S. (2016). The temporal stability of lack of sexual attraction across young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 743–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0583-4

Davis, D., Shaver, P. R., & Vernon, M. L. (2004). Attachment style and subjective motivations for sex. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(8), 1076–1090. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264794

Dawson, M., McDonnell, L., & Scott, S. (2016). Negotiating the boundaries of intimacy: The personal lives of asexual people. The Sociological Review, 64(2), 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12362

Dawson, M., Scott, S., & Mcdonnell, L. (2019). Freedom and foreclosure: Intimate consequences for asexual identities. Families, Relationships and Societies, 8(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674317X15011694317558

Decker, J. S. (2015). The invisible orientation: An introduction to asexuality. Skyhorse.

Diamond, L. M. (2016). Sexual fluidity in male and females. Current Sexual Health Reports, 8(4), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-016-0092-z

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2019). Gender/sex, sexual orientation, and identity are in the body: How did they get there? The Journal of Sex Research, 56(4–5), 529–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1581883

Foster, A. B., Eklund, A., Brewster, M. E., Walker, A. D., & Candon, E. (2019). Personal agency disavowed: Identity construction in asexual women of color. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000310

Fraley, R. C., & Shaver, P. R. (2000). Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology, 4(2), 132–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.4.2.132

Gentzler, A. L., & Kerns, K. A. (2004). Associations between insecure attachment and sexual experiences. Personal Relationships, 11(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00081.x

Glatzer, J. (2021). What does it mean to be aceflux? This micro-label is gaining traction in the asexual community. Mic. https://www.mic.com/life/what-does-it-mean-to-be-aceflux-this-micro-label-is-gaining-traction-in-the-asexual-community-82808464

Greaves, L. M., Barlow, F. K., Huang, Y., Stronge, S., Fraser, G., & Sibley, C. G. (2017). Asexual identity in a New Zealand national sample: Demographics, well-being, and health. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(8), 2417–2427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0977-6

Gupta, K., & Cerankowski, K. J. (2017). Asexualities and media. In C. Smith, F. Attwood, & B. McNair (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media, sex and sexuality (pp. 19–26). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315168302-3

Guz, S., Hecht, H. K., Kattari, S. K., Gross, E. B., & Ross, E. (2022). A scoping review of empirical asexuality research in social science literature. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(4), 2135–2145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02307-6

Hayfield, N. (2020). Bisexual and pansexual identities: Exploring and challenging invisibility and invalidation. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429464362

Herek, G. M., Norton, A. T., Allen, T. J., & Sims, C. L. (2010). Demographic, psychological, and social characteristics of self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in a US probability sample. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7(3), 176–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-010-0017-y

Hille, J. J., Simmons, M. K., & Sanders, S. A. (2020). “Sex” and the ace spectrum: Definitions of sex, behavioral histories, and future interest for individuals who identify as asexual, graysexual, or demisexual. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(7), 813–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1689378

Höglund, J., Jern, P., Sandnabba, N. K., & Santtila, P. (2014). Finnish women and men who self-report no sexual attraction in the past 12 months: Prevalence, relationship status, and sexual behavior history. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(5), 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0240-8

Horowitz, J. L., & Newcomb, M. D. (2001). A multidimensional approach to homosexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality, 42(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1300/j082v42n02_01

Impett, E. A., Gordon, A. M., & Strachman, A. (2008). Attachment and daily sexual goals: A study of dating couples. Personal Relationships, 15(3), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00204.x

Jones, C., Hayter, M., & Jomeen, J. (2017). Understanding asexual identity as a means to facilitate culturally competent care: A systematic literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), 3811–3831. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13862

Kelleher, S., & Murphy, M. (2022). Asexual identity development and internalisation: A thematic analysis. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2022.2091127

Kerpelman, J. L., & Pittman, J. F. (2018). Erikson and the relational context of identity: Strengthening connections with attachment theory. Identity, 18(4), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2018.1523726

Lafortune, D., Girard, M., Bolduc, R., Boislard, M.-A., & Godbout, N. (2022). Insecure attachment and sexual satisfaction: A path analysis model integrating sexual mindfulness, sexual anxiety, and sexual self-esteem. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 48(6), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2021.2011808

MacNeela, P., & Murphy, A. (2015). Freedom, invisibility, and community: A qualitative study of self-identification with asexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(3), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0458-0

Mark, K. P., Vowels, L. M., & Murray, S. H. (2018). The impact of attachment style on sexual satisfaction and sexual desire in a sexually diverse sample. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(5), 450–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2017.1405310

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Press.

Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Pereg, D. (2003). Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion, 27(2), 77–102. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024515519160

Mitchell, H., & Hunnicutt, G. (2019). Challenging accepted scripts of sexual “normality”: Asexual narratives of non-normative identity and experience. Sexuality & Culture, 23(2), 507–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9567-6

Mollet, A. L. (2021). “It’s easier just to say I’m queer”: Asexual college students’ strategic identity management. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 16(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000210

Mustanski, B., Birkett, M., Greene, G. J., Rosario, M., Bostwick, W., & Everett, B. G. (2014). The association between sexual orientation identity and behavior across race/ethnicity, sex, and age in a probability sample of high school students. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301451

Prause, N., & Graham, C. A. (2007). Asexuality: Classification and characterization. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(3), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9142-3

Rholes, W. S. (1996). Conflict in close relationships: An attachment perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(5), 899–914. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.71.5.899

Robbins, N. K., Low, K. G., & Query, A. N. (2016). A qualitative exploration of the “coming out” process for asexual individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 751–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0561-x

Rosario, M., Schrimshaw, E. W., Hunter, J., & Braun, L. (2006). Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time. The Journal of Sex Research, 43(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490609552298

Rothblum, E. D., Krueger, E. A., Kittle, K. R., & Meyer, I. H. (2020). Asexual and non-asexual respondents from a U.S. population-based study of sexual minorities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(2), 757–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01485-0

Scherrer, K. S. (2008). Coming to an asexual identity: Negotiating identity, negotiating desire. Sexualities, 11(5), 621–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460708094269

Scott, S., & Dawson, M. (2015). Rethinking asexuality: A symbolic interactionist account. Sexualities, 18(1–2), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460714531273

Sennkestra. (2020). Differentiating attraction/orientations (or, the “split attraction model” by any other name is so much sweeter.). Next Step: Cake. https://nextstepcake.wordpress.com/2020/04/30/naming-differentiating-attraction-orientations/

Shaver, P. R., Schachner, D. A., & Mikulincer, M. (2005). Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(3), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271709

Siggy. (2019). Splitting the split attraction model. The Asexual Agenda. https://asexualagenda.wordpress.com/2019/04/02/splitting-the-split-attraction-model/

Simpson, J. A., & Rholes, W. S. (2017). Adult attachment, stress, and romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.006

Su, Y., & Zheng, L. (2023). Stability and change in asexuality: Relationship between sexual/romantic attraction and sexual desire. The Journal of Sex Research, 60(2), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2045889

Tracy, J. L., Shaver, P. R., Albino, A. W., & Cooper, M. L. (2003). Attachment styles and adolescent sexuality. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 137–159). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Van de Meerendonk, D., & Probst, T. M. (2004). Sexual minority identity formation in an adult population. Journal of Homosexuality, 47(2), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v47n02_05

Van Houdenhove, E., Gijs, L., T’Sjoen, G., & Enzlin, P. (2014). Asexuality: Few facts, many questions. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40(3), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2012.751073

Van Houdenhove, E., Gijs, L., T’Sjoen, G., & Enzlin, P. (2015). Stories about asexuality: A qualitative study on asexual women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(3), 262–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2014.889053

Vrangalova, Z., & Savin-Williams, R. C. (2012). Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: Evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9921-y

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2014). Sexual fantasy and masturbation among asexual individuals. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 23(2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2409

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2015). A validated measure of no sexual attraction: The Asexuality Identification Scale. Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038196

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2017). Sexual fantasy and masturbation among asexual individuals: An in-depth exploration. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(1), 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0870-8

Zheng, L., & Su, Y. (2018). Patterns of asexuality in China: Sexual activity, sexual and romantic attraction, and sexual desire. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 1265–1276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1158-y

Acknowledgements

We want to thank AVEN for their help in collecting data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). Part of this work was funded by grants awarded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia to ACC (Ref.: 2023.01784.BD), and DLR (Ref.: 2020.00523.CEECIND).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ACC and DLR conceived the study. ACC collected the data and performed statistical analyses, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. DLR coordinated the study, reviewed the data analyses, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All study procedures and measures were in accordance with the guidelines issued by the Ethics Council of Iscte-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, and was in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carvalho, A.C., Rodrigues, D.L. Belonging to the Ace Spectrum: Correlates of Cognitions, Feelings, and Desires of Ace Individuals. Sex Res Soc Policy (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00910-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00910-3