Abstract

Comprehensive sexuality education may help prevent intimate partner violence, but few evaluations of sexuality education courses have measured this. Here we explore how such a course that encourages critical reflection about gendered social norms might help prevent partner violence among young people in Mexico. We conducted a longitudinal quasi-experimental study at a state-run technical secondary school in Mexico City, with data collection including in-depth interviews and focus groups with students, teachers, and health educators. We found that the course supported both prevention of and response to partner violence among young people. The data suggest the course promoted critical reflection that appeared to lead to changes in beliefs, intentions, and behaviors related to gender, sexuality, and violence. We identify four elements of the course that seem crucial to preventing partner violence. First, encouraging participants’ reflection about romantic relationships, which helped them question whether jealousy and possessive behaviors are signs of love; second, helping them develop skills to communicate about sexuality, inequitable relationships, and reproductive health; third, encouraging care-seeking behavior; and fourth, addressing norms around gender and sexuality, for example demystifying and decreasing discrimination towards sexually diverse populations. The findings reinforce the importance of schools for violence prevention and have implications for educational policy regarding sexuality education. The results suggest that this promising and relatively short-term intervention should be considered as a school-based strategy to prevent and respond to partner violence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Comprehensive sexuality education may help prevent intimate partner violence among young people by addressing inequitable relationships and the harmful gender norms that perpetuate violence. Despite this possibility, few evaluations of sexuality education have examined whether and how these programs can prevent or mitigate intimate partner violence, which can be defined as “any behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm to those in the relationship” (Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg, & Zwi, 2002). Instead of measuring outcomes related to violence, studies evaluating sexuality education typically document reductions in HIV, sexually transmitted infection, and unintended pregnancy rates (Fonner, Armstrong, Kennedy, O’Reilly, & Sweat, 2014; Kirby, 2008; Kirby, Laris, & Rolleri, 2006).

It is important to identify which aspects of interventions are most likely to help prevent intimate partner violence. Sexuality education has long been conceptualized as tackling violence and gender equality in addition to providing information about health and sexuality (Report of the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 5–13 September 1994, 1995). Drawing from this framework, what is termed an “empowerment approach” to sexuality education incorporates content about gender and power to promote equitable relationships (Haberland & Rogow, 2015; UNFPA, 2015; United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2018). According to a comprehensive review of 22 studies, sexuality education and HIV prevention programs that address the topics of gender and power dynamics within intimate partnerships are five times more likely to reduce rates of sexually transmitted infection and unintended pregnancy than programs that exclude these topics (Haberland, 2015). The same review concludes that it is important to incorporate gender and power as themes in sexuality education in order to address harmful gender norms and “increase the chances that young people will have relationships characterized by equality, respect and nonviolence.” A qualitative study in Cambodia and Uganda similarly found that comprehensive sexuality education holds promise to prevent violence against women and girls by promoting gender equitable attitudes, life skills, and changes in community norms (Holden, Bell, & Schauerhammer, 2015).

Gender norms and other social norms influence the perpetration of violence (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, 2015; Jewkes, Flood, & Lang, 2015). For instance, the IMAGES study in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico found that perpetration of partner violence is associated with behaviors and beliefs corresponding with dominant expressions of masculinity (Barker, Aguayo, & Correa, 2013). Norms also reflect social expectations in terms of gendered behaviors, including sexual behaviors and preferences—for instance defining socially acceptable ways to behave in relationships or express one’s sexuality (Marston, 2005; Pulerwitz & Barker, 2008). Gender norms are of particular relevance for young people, who are in the process of gender socialization (Blum, Mmari, & Moreau, 2017; Chandra-Mouli et al., 2017). Social norms related to gender and sexuality may even be reinforced in school settings, which are often heteronormative (Toomey, McGuire, & Russell, 2012; Youdell, 2005); some of these norms may be a source of not only partner violence but also interpersonal violence in schools, such as bullying based on gender identity or sexual orientation.

Across diverse contexts and types of interventions, a “gender-transformative” approach—aiming to shift social norms, particularly harmful gender norms—has been shown to be a central component of programs that reduce partner violence (Ellsberg et al., 2015; Fulu & Kerr-Wilson, 2015; Heise, 2011; Jewkes et al., 2008; Pulerwitz et al., 2010; Ricardo, Eads, & Barker, 2011; Rottach, Schuler, & Hardee, 2009; Verma et al., 2008). A promising strategy for interventions that aim to shift social norms is to work with a group of individuals who will become agents of change to influence their community (Cislaghi & Heise, 2018). This approach is used by Hombres Unidos Contra La Violencia Familiar (Men United Against Family Violence), a violence prevention program working with Hispanic men in the USA that demonstrated promising results such as participants rethinking their ideas about violence and engaging in conversations in their community about partner violence (Nelson et al., 2010). The SASA! program in Uganda also takes this approach, and the program has contributed to more egalitarian relationship dynamics as well as being associated with reductions in reported intimate partner violence (Kyegombe et al., 2014; Starmann et al., 2017). Evaluations of both these programs also identified facilitator-led group discussion as a key strategy to encourage reflection about violence-related social norms (Kyegombe et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2010). These strategies to shift social norms, as well as other elements that are considered central to prevention of partner violence, are also included in international standards for comprehensive sexuality education (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2018). However, these guidelines are not always implemented (Montgomery & Knerr, 2018) and so the effects of well-implemented sexuality education programs on violence prevention remain unclear. Whether sexuality education that adopts an empowerment approach and addresses harmful gender norms can prevent intimate partner violence in different settings—and how it might do this—requires further investigation.

In addition to the scarcity of research evaluating how sexuality education may address partner violence, there are further gaps in the literature about prevention. For example, there is little research in low- and middle-income countries about the “primary prevention” of partner violence—intervening to prevent violence before it takes place (Arango, Morton, Gennari, Kiplesund, & Ellsberg, 2014; Ellsberg et al., 2015). We also lack evidence about effective strategies that prevent partner violence among adolescent girls (Blanc, Melnikas, Chau, & Stoner, 2013), who may be at elevated risk of this type of violence (Abramsky et al., 2011; Morrison, Ellsberg, & Bott, 2007; World Health Organization, 2013). The growing literature on violence prevention calls for more research in low- and middle-income countries that examines not only program effectiveness but also how the process of change happens (Fulu & Kerr-Wilson, 2015; Kyegombe et al., 2014; Starmann et al., 2017). This longitudinal study responds to these gaps in evidence by examining the mechanisms through which a comprehensive sexuality education intervention in Mexico may support the prevention of intimate partner violence among young people.

Intimate partner violence is common in Mexico: According to recent estimates, 44% of women aged 15 years and older in Mexico report at least one incident of partner violence in their lifetime (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2018b). In a different study, over half of students surveyed at the Mexican National Polytechnic Institute reported ever experiencing romantic jealousy in a relationship (Tronco Rosas & Ocaña López, 2012). In addition, 10% of women and 13% of men reported having exerted controlling behaviors, such as monitoring a partner’s cell phone, email, or social media, more than once in a relationship (Tronco Rosas & Ocaña López, 2012). The researchers note that these behaviors are often perceived as displays of caring but may indicate or lead to relationship violence (Tronco Rosas & Ocaña López, 2012).

Nearly 39% of the Mexican population is younger than 20 years old (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2018a) and the country has high rates of school attendance (98% in primary and 79% in secondary school) (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2015). Despite some opposition in Mexico, school-based sexuality education in Mexico has potential for substantial reach (Chandra-Mouli, Gómez Garbero, Plesons, Lang, & Corona Vargas, 2018) and could contribute to violence prevention. In 2016, Fundación Mexicana para la Planeación Familiar (Mexfam), a non-governmental organization that provides clinical and community-based health care services in Mexico, revised its comprehensive sexuality education curriculum to include content explicitly aimed at preventing intimate partner violence. This work built on prior versions of the program that had been found to improve communication about sexuality among young people and influence gender norms (Marston, 2004).

The updated comprehensive sexuality education course comprises 20 hours of curriculum delivered over a semester in weekly sessions by young people (aged 30 or younger) who are staff health educators for Mexfam’s Gente Joven (“Young People”) program. The course uses a gender-transformative approach, tackles gender and power dynamics as cross-cutting themes, and includes a comprehensive set of topics including sexuality, intimate partner violence, unintended pregnancy, and relationships. The course employs participatory techniques and encourages critical reflection on violence and gendered social norms. Students are given information on where and how to seek support for sexual and reproductive health and violence and are told about their right to seek health services. For brevity, in this paper we will refer to the comprehensive sexuality education course with a violence prevention component run by Mexfam as “the course,” and unless stated otherwise, all mention of violence refers to intimate partner violence.

Mexfam partnered with International Planned Parenthood Federation/Western Hemisphere Region and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to pilot, implement and evaluate their updated comprehensive sexuality education course using mixed methods of data collection. This article presents participant experiences as well as how the course appears to support the process of prevention and response to intimate partner violence.

Methods

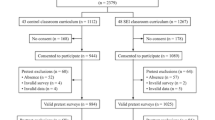

In 2017 and 2018, we conducted a longitudinal quasi-experimental study in Mexico City. The analysis presented in this article reflects primarily qualitative data focusing on the intervention group. Baseline sociodemographic and descriptive statistics for the intervention group are presented in Table 1; further quantitative analysis is not yet complete and is not presented here. The study took place at a state-run technical secondary school located in a commercial zone of the Tlalpan area in the southern part of the city. The school operates morning and afternoon sessions, each with different students and teachers, delivering vocational training in subjects such as automotive mechanics and food preparation. Students are primarily from lower-middle income families from Mexico City (Gómez Espinoza, 2006), and travel to the school from different parts of the city. We first conducted a pilot in one classroom of the afternoon session and then used a coin toss to assign the school’s morning program to receive the course the following semester, with three classrooms participating.

We aimed to explore the ways the course may contribute to preventing partner violence, in line with the call for studies that examine the mechanisms of violence prevention (Starmann et al., 2017). In the planning phase, program and research staff collaboratively developed a series of hypotheses about how the program might affect participants, for example learning to identify different types of partner violence, shifting attitudes about violence and gender norms, sharing information about violence, gender or sexuality with peers, seeking support and services if they experience violence, and ultimately experiencing less violent or more equitable relationships. We grouped these hypotheses into what we termed a “theory of change” (Breuer, Lee, De Silva, & Lund, 2016; Silva et al., 2014), which informed the data collection methods and data analysis.

Students in the intervention classrooms were told by school officials that they were expected to participate in the comprehensive sexuality education course during a weekly tutoring session, but that taking part in the study was optional. Students who were 14 to 17 years old, provided informed consent, and obtained parental consent were eligible to participate in the study. Of the 185 students receiving the course in the pilot and intervention semesters, 157 (85%) were eligible and agreed to participate in this study. They were asked to complete a baseline questionnaire in which they self-reported age, sex, relationship status, sexual history, and experience of intimate partner violence. We used these baseline responses from students receiving the intervention to purposively select a subsample for qualitative data collection that was heterogeneous with regard to the reported characteristics. In addition, some students who were not originally sampled approached the research team and asked to participate in interviews or focus groups. If eligible for the study, they were invited to participate even if they had not completed a baseline questionnaire. In total, 47 students (30% of students receiving the intervention) comprised the subsample participating in interviews and focus groups. Table 1 presents baseline sociodemographic and descriptive data for this qualitative subsample and the intervention group as a whole.

In addition to students, we also invited all teachers assigned to the intervention classrooms and all Mexfam health educators providing sexuality education to these classes to participate in focus group discussions, after obtaining written informed consent. We gave all focus group and interview participants a gift card as compensation for their time and offered them subsidized services through Mexfam’s network of clinics. This study was approved by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee in the UK and Bioética y Ciencia para la Investigación (CICA) in Mexico.

Qualitative data collection methods with course participants were as follows: We used observation throughout the semester to better understand how students interact and engage during the course. We used case studies to explore participant trajectories (Grossoehme & Lipstein, 2016) during the intervention, conducting up to four interviews with each of nine course participants (five female, four male) approximately monthly throughout and up to three months after the intervention. After the intervention ended, we selected an additional 10 male and 10 female course participants for one-off in-depth interviews and conducted three focus group discussions, two with young men (n = 18) and one with young women (n = 6). Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of interview and focus group participants.

We also conducted separate focus group discussions with five teachers and five health educators after the pilot semester and after the full intervention (participant characteristics detailed in Table 2). All five teachers were women; we did not collect age data. The health educators had a mean age of 26.4 years, ranging from 23 to 29 years old. Four were women and one was a man. Two of the health educators participated in both focus groups.

Mexfam staff and local professional transcriptionists carried out verbatim transcription of audio-recorded interviews and focus groups. Two team members (JG and SM) listened to all of the interviews and spot-checked transcription quality. Two team members (SM and CM) led data analysis using the original transcripts in Spanish. We created a “start list” of codes based on the research questions and hypotheses (Miles & Huberman, 1994). We then reviewed and indexed all transcripts according to these codes. We created new codes throughout the process to capture emerging concepts, allowing for a “combination of data-driven and theory-driven strategies of category creation” (Gläser & Laudel, 2013). We used a “progressive focusing” approach, iteratively adjusting the codes and data collection processes as we became familiarized with the data and refined our focus of inquiry (Schutt & Chambliss, 2013; Sinkovics & Alfoldi, 2012; Stake, 1981). Once most transcripts were indexed, we began subsequent analysis by developing code summaries (Miles & Huberman, 1994) to compile and integrate data from different sources and begin to draw conclusions pertaining to each of our hypotheses. We used analytic memo-writing to aid the analysis process (Saldaña, 2009) and examined longitudinal data to explore “epiphanies,” “tipping points,” and the “unfolding” of gradual change (Farrall, 1996). One team member (SM) translated the final quotations selected for this paper in discussion with the other authors (native speakers of Spanish and English) to capture nuance, using “…” to designate omitted text. We periodically conducted meetings to discuss emerging findings. We refer to participants using pseudonyms.

Results

We found that Mexfam’s comprehensive sexuality education course influenced participants in the following principal areas which we will discuss in turn below: critical reflection about social norms; shifts in attitudes and knowledge about violence and gender; increased communication about relationships, sexuality, and violence; taking protective and preventative actions related to violence, relationships, and sexual and reproductive health; and changing norms around gender and sexuality.

Critical Reflection and Attitude Shifts Related to Violence and Relationships

Students, health educators, and teachers told us that during the course many participants reconsidered their perceptions of jealous and controlling behaviors that occur in relationships, such as monitoring a partner’s social media. They said the course encouraged reflection and debate about the types of violence that can occur in relationships as well as the positive attributes of relationships. Some participants described reflecting on their own behavior and experiences as a result of using the Violentómetro tool (Tronco Rosas, 2012), which was presented in the course, to analyze whether they were experiencing violence in their own relationships. The tool, developed based on formative research in Mexico (Tronco Rosas & Ocaña López, 2012), visually depicts manifestations of partner violence ranging from subtle to severe, including types of psychological, physical, and sexual violence.

Students and health educators frequently mentioned that the group discussions in the course played a role in the process of reflecting on participants’ perceptions of jealousy and controlling behaviors in relationships.

There is a lot of ‘close your Facebook, we’ll only use messenger’, or ‘block that boy [on your social media]’ or ‘don’t dress that way’ or ‘why are you talking to him’ … or many [such] things, right? And, well, we thought that this was fine, they do it because they love me.… And then [the facilitator] made it very clear to us that this is not because they love you, but actually because they are a possessive person. That is, if they really loved you they would accept you as you are. (Laura, young woman, 16)

Some participants said that before the course they did not think jealousy in a relationship was problematic but during the course they realized that it was. Julián said he now believes jealousy “is bad, because if you have trust in your partner, why are you going to be jealous over them?” but that before the course he thought it was a way to show love: “I used to say … that if they weren’t jealous then they didn’t love you, things like that” (Julián, young man, 15). Julián and other participants said they now considered jealousy to be a negative attribute in a relationship, but this view was not universal among the interviewees. “Jealousy can be good because, well, it is a way to express that you care about the person. But if it becomes excessive it can be dangerous” (Vicente, young man, 15).

Alberto said that before the course many classmates believed that jealousy was a sign of love, but that even while they were starting to change their views, a television program showing at the same time as the course was promoting the opposite message.

There was a moment when the penny dropped for them [i.e. they realized that jealousy was bad], but afterwards the famous [television] program Enamorándonos [Loving each other] began … and the famous sexologist said, ‘if there wasn’t any jealousy, there wasn’t any love.’ And—I think that put them [my classmates] back to where they had been before the course. (Alberto, young man, 15)

Some participants mentioned that the course highlighted not only aspects of relationships that should be avoided, such as manifestations of violence, but also positive attributes of relationships. “We used an amorómetro [love thermometer] that started with trust, respect, avoiding jealousy. And [learned that] by avoiding jealousy most of your problems will stop. Because most problems come from jealousy” (Young man, focus group).

One teacher said she observed students questioning and reflecting on their ideas about relationships and love during the course.

For them, at this age, is it really love? Or is it a simple preference, or is it simply affection? [These questions] often confuse [them]. So for them … to be able to reflect …, to engage again [with these ideas] and reflect about their interpersonal relationships, such as friends with benefits, or friend-boyfriend, or friend or acquaintance—that is what they experienced [in the course]. (Teacher)

Critical Reflection About Gender, Sexuality, and Relationships

Some participants said the course encouraged them to reflect on their beliefs about gender and sexuality, for example during facilitated activities in which the group engaged with and questioned prevailing social norms, such as those related to gender equity. “We were debating and [pause] came to the conclusion that [pause] they [women and men] are equal, that women can do what men can do, and men can help women and women can help men” (Alberto, young man, 15). Others said that hearing what classmates said during the group discussion helped them reflect on their own individual beliefs.

One of the things my classmate said stayed with me. He said that the man has to work and the woman [should stay] in the house…. It made me, like, think.… I think that a woman doesn’t need to always be at home… um, as if it were a prison.… I think you need to give freedom to both people in a relationship. (Marco, young man, 15)

Some participants said they changed their personal attitudes about gender and sexuality during the course, and several said that the course helped them accept their own sexuality and feel more confident talking about it.

Before, I was not sure of myself.…. And … well, it turns out that … various lessons during the course … helped me reflect and … realize … whether I was [bisexual] or not, that I was born this way, and this is who I am. (Karina, young woman, 15)

Several participants also said the course helped them develop more self-respect and confidence in their ability to make the right decisions about relationships and sexuality. For example, one participant told us the course helped her reflect and come to the conclusion that she was not ready to start having sex. One teacher said that she thought the course helped prepare young people for their interpersonal and romantic relationships.

From what I observed during the course sessions, it seems to me that for the participants it was a watershed moment, it created a different vision for their own lives, their family life, their relationship with school, and friends, and above all to help them rethink—as young people—the sexual and emotional direction of their lives. (Teacher)

Increased Communication About Relationships and Sexuality

Students, teachers, and health educators said that participants became more comfortable talking about relationships and sexuality as the course progressed.

Before the course, it made us … a bit embarrassed to talk about [sexual and reproductive health]. But afterwards we understood, with the course, that it was, like, very natural to talk about it. It’s like any other thing, and so I now feel fine talking about it. (Gerardo, young man, 15)

Several students also said that when the Mexfam health educators shared their own personal experiences during the sessions it helped the course participants to open up about their own lives.

For some, an important part of the course was hearing the other participants’ views. For some participants, this process helped them identify supportive peers. For example, one focus group participant said it was valuable to know what her classmates thought about the course topics, and another participant added that this helped them know who they could trust. “I know that all the women in my class … think the same as me, and I know that if anything ever, well, happens to me, I know I can talk to any of them about it” (Young woman, focus group).

Protective and Preventative Actions Related to Violence and Health

Participants in this study told us that they engaged in a range of direct actions to mitigate or respond to violence in their own relationships and those around them. Many participants said they shared the information learned in the course about relationships and violence with their friends and family members, and some said they intervened in violence around them during or after the course.

[Her boyfriend] told her that without him she was nothing, that she would never find anyone better than him.… She told us, well, that she wanted to leave him but … that he, well, wouldn’t allow it. And the other [friend] was just … she was sad because she didn’t want to be with her boyfriend anymore … and he told her that if she left him, he would kill himself. So we told her that no, that she should leave him, that [pause] she should tell his mother, someone who can take care of him.… So, because of the course I already knew how I could help. (Judith, young woman, 14)

A handful of participants said they talked with their partners about different types of violence versus positive aspects of relationships.

When they told us … about what is love and what is not love.… I told him [my boyfriend] ‘… they told us that jealousy is bad’, and he replied, ‘that’s right, because it means a lack of trust’, and in this way, we sometimes talked about [the course contents]. (Silvia, young woman, 14)

One participant said the course prompted him to talk with his girlfriend about his dislike of her controlling behavior in their relationship. Others said that they noticed changes in their classmates’ relationships. For example, one participant told us about a male classmate who at first would not let his girlfriend talk to other men, but then “his way of thinking changed and he relaxed about it” once the course began to address the topic of relationship violence (Marco, young man, 15). Another participant said a classmate had disclosed to the class that she had spoken to her boyfriend about the violent behaviors in their relationship and believed the relationship had improved as a result. Several individuals also told us that classmates had left controlling or violent relationships during or because of the course.

[The course] left them with a clear idea of what was really going on in their relationship, so they decided [to leave], saying ‘it’s true, it’s not that he loves me. This [being possessive over me] is a type of violence.’ (Laura, young woman, 16)

Students and health educators told us that course participants approached members of the Mexfam team for advice and support related to relationships and partner violence, either for themselves or to get advice on how to support friends who were experiencing violence.

There was one classmate, [the topic of] relationship violence made a big impression on her.… Because I think her boyfriend used to be, well, jealous. He used to ask for her cell phone and things like that. And, well, I think that she approached one of the girls [health educators]. And she also asked for help. (Gerardo, young man, 15)

Several Mexfam health educators said that course participants came to them to ask for information or support related to relationship violence, as in the case of one young woman who said she was scared to leave a jealous boyfriend.

A young woman … approached me and said ‘I just got back together with my boyfriend, but he is very jealous.’ And I told her about her options [to address her situation], and she told me ‘I’m going to use one of those options … but I’m scared.’ (Health educator)

The course helped participants learn that it was possible for them and other young people to seek support at Mexfam or at other health centers, and to ask for help from the health educators.

[The health educators] are people you can trust. As time passed, well, they gave me confidence … that if at any moment something happens and I need something, or want to know something … well, I can ask them for help, it won’t be a problem. At the beginning I felt a bit embarrassed [talking to them], but afterwards, no, I would feel relaxed. (Miguel, young man, 15)

One health educator said that as part of the course, they deliberately reinforced reflection about young people’s right to services by repeatedly extending invitations to health services and reminding participants that it was their right to access these services. Another health educator said that they observed participants begin talking during the course about their right to healthcare, and speculated that before the course they would not have considered it their right to access that healthcare.

The health educators said that participants contacted them in various ways, both during and after the course. Some approached them in person, often towards the end of the semester once they had developed trust in the health educators, and others contacted them by phone or Whatsapp. When the course ended, Mexfam organized a health fair at the school during which they provided free health services to a number of course participants in the organization’s mobile health unit. The Mexfam team said that course participants generally approached their mobile health unit rather than those of other organizations offering services at the health fair, and suggested that this may relate to the trust the students had developed in the health educators during the course.

Changing Norms Around Gender and Sexuality

Participants described how they or their classmates changed their beliefs and behaviors relating to gender and sexuality. Several students and health educators said that participants shifted the way they spoke about these topics during the course.

[The course helped] a classmate, because he … used to make this type of comment [disparaging women], and after this I also tried to explain to him that you have to respect women.… He no longer makes that sort of comment. (Alejandro, young man, 16)

Some participants said the course taught them to engage in dialogue or communicate assertively about sexuality or gender. When asked whether he spoke with peers about the topics discussed in the course, one young man said he engaged in conversations about sexual diversity by asking questions of a classmate who identified as gay. Another participant told us:

I had a classmate who used to say that gay people disgusted him.… And then after the course he started assimilating things and then he didn’t think in that way anymore.… [Beforehand] I used to hang out with him but he didn’t know I was bisexual […]. Afterwards … he asked me if I was gay, and I said that ‘no, I’m bisexual’. And he said to me ‘that’s fine, you’re all right.’… After that, he changed his way of thinking. (Gerardo, young man, 15)

Students and health educators told us that a few course participants approached the Mexfam team to talk about how harmful gender norms affected their lives and to seek support. One young man who identified as homosexual told us he enjoyed wearing makeup, and that his family tried to prevent him from doing so. He said he wanted to bring his mother to Mexfam so she would learn to accept his gender expression.

I said [to my mother], it isn’t fair that you criticize me, because you are completely interfering with the person I am.…. I told my mother, if you want I’ll invite you to Mexfam, so that … they can tell you that it isn’t ok for you to interfere with the way I am. (Gilberto, young man, 17)

Judith also asked for help from the course facilitators so that her mother would begin to understand her and accept her sexual orientation. Similarly, a health educator said that after the last session of the course, a young woman asked for information about how to work with her mother to accept her sexuality.

Another health educator said that a course participant, who was in her first year of secondary school, approached them to discuss the gender beliefs in her family, specifically their resistance to her attending school because she was a woman.

She said to me, ‘… I think that it is economic violence.’ I asked her why. ‘It’s that they don’t give me [money] for food …, for transportation.… I already talked to them and they told me that I don’t have the right [to study] because I’m a woman. And I should get home and take care of my family.’ (Health educator)

Discussion

Our study adds to the growing literature that suggests that changes in behaviors and beliefs that support the prevention of partner violence can be achieved in programmatic timeframes. We found that comprehensive sexuality education may help prevent intimate partner violence among young people, both in terms of prevention—addressing the harmful gender norms that underlie inequitable relationships as well as other risk factors for violence—and response—preparing young people to address and mitigate such violence if it happens. Our findings show how comprehensive sexuality education appears to help young people take a critical approach to social norms and respond to them accordingly. Students, teachers, and health educators credited Mexfam’s course with influencing a range of attitudes and practices compatible with the objectives of gender-transformative programming and violence prevention efforts (Dworkin, Fleming, & Colvin, 2015).

This study also responds to the call for research that examines the process of violence prevention. The course appears to promote critical reflection that helped change beliefs, intentions, and behaviors related to gender, sexuality, and violence. Reflection has also been shown elsewhere to support attitude and behavior change in related areas (Kyegombe et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2010). Aspects of Mexfam’s course that likely contributed to this process include the use of content relevant to participants’ lives and activities such as discussing vignettes designed to promote critical engagement with social norms. Group discussions promoting open dialogue between participants and facilitators provide a space to share experiences and beliefs, debate about contradictions among these, and begin to create individual and collective narratives that help them engage with and resolve dilemmas related to the course topics. The facilitators play a crucial role in ensuring the space is safe for what is sometimes very sensitive discussion, and it is clearly important for them to be adequately trained and supported if they are to be effective, a consideration noted in international guidelines for comprehensive sexuality education (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2018). This may be of relevance for programs expecting teachers to deliver a comprehensive sexuality education curriculum with a gender-transformative approach, as they should not only be comfortable with course topics but also prepared to engage participants in critical reflection processes.

Young people are likely to encounter messages and information coming from credible sources that counter the teachings of a sexuality education course, as in the case of the television show asserting that jealousy is a sign of love; a short-term intervention may not be able to counter these contradictory societal messages, but can create space for reflection and assertive communication about different—for example, religious, cultural, or scientific—understandings of love. By promoting critical reflection, comprehensive sexuality education may directly contribute to shifts in social norms. For example, facilitated group discussions questioning dominant ideas about gender equity and violence created opportunities for course participants to reconsider their beliefs, renegotiate norms within their group, and later diffuse these shifts in ideas and norms within their community—a strategy for social norms change also reported elsewhere (Cislaghi & Heise, 2018; Miller & Prentice, 2016). We would suggest that this is a way that comprehensive sexuality education supports the prevention of intimate partner violence.

We identify four key elements of the course that seem crucial to supporting violence prevention: First, encouraging participants’ reflection about romantic relationships, which helped them question whether jealousy and possessive behaviors are signs of love; second, helping them develop skills to communicate about sexuality, the characteristics of inequitable relationships, and reproductive health; third, encouraging care-seeking behavior; and fourth, addressing norms around gender and sexuality, for example demystifying and decreasing discrimination towards sexually diverse populations.

Mexfam’s comprehensive sexuality education course helped participants consider a range of narratives of how love can be expressed, for example by rethinking jealousy and possessive behaviors as unwanted practices. This reconceptualization, which was encouraged in the course, contradicts the maintream construction of jealousy and controlling behaviors as a part of romantic love in Mexico (Flecha, Puigvert, & Redondo, 2005; Ruiz, 2015; Tronco Rosas, 2012; Tronco Rosas & Ocaña López, 2012). The Violentómetro (Tronco Rosas, 2012; Tronco Rosas & Ocaña López, 2012) helped participants to identify and reflect on these and other subtle or less subtle forms of relationship violence. Building on the acceptability and usefulness of the Violentómetro, Mexfam used a similar format to showcase positive and equitable relationship behaviors that could replace unwanted or violent practices.

Developing communication skills was also important. Course activities appeared to help participants overcome their embarrassment and become more confident talking about sexual and reproductive health topics in a mixed-gender environment during the course. This also appears to have prepared them to communicate about these topics outside the course with family, peers, and partners. The group discussions during the course likely helped participants to give and seek advice about sexuality, relationships, and violence within a supportive network of peers. By sharing information learned in the course with others, participants may well have created indirect effects in their social network that we have not been able to measure. Comprehensive sexuality education programs seeking to shift gender norms could explicitly support participants to be agents of change in their communities, as in other violence prevention programs (Kyegombe et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2010; Starmann et al., 2017) and other community programming seeking to shift social norms (Cislaghi, 2018).

The course encouraged participants to seek professional advice and support regarding sexual and reproductive health and relationships, with some students approaching Mexfam for information and referrals and a smaller number reporting that they or their peers accessed health services. This suggests that the course may have helped address some of the barriers to sexual and reproductive health and partner violence services commonly encountered by young people (Mejía et al., 2010; Santhya & Jejeebhoy, 2015). This may relate to the health educators’ work emphasizing the right of young people to receive services, building trust with the students, providing frequent referral to trusted providers, and being accessible by phone, social media, and text message applications such as Whatsapp. After the course ended, some participants continued to contact the health educators through these avenues, and Mexfam sustained contact with students by providing information and services on school grounds using mobile health units during a school-wide health fair.

The course addressed social norms related to gender and sexuality, for example by demystifying sexual diversity and tackling homophobic discrimination. It may be that participants who are grappling with their own sexuality or gender identity were particularly motivated to engage with the course, but in any case, the positive impact reported by gay, lesbian, bisexual, and questioning participants in the course highlights the importance of avoiding heteronormativity and addressing sexual diversity in sexuality education programs. Engaging families and teachers, which was not done as part of the evaluated intervention, might improve parent-child communication and avenues for support within the school context, which could have particular benefits for those young people who find it challenging to communicate about their sexuality, are at risk of discrimination related to their sexual orientation or gender identity, or are particularly vulnerable to intimate partner violence.

One of this study’s strengths is the close collaboration between the research and programmatic teams throughout the research process, which helped ensure that study findings would be programmatically relevant and put into practice. The study also had limitations. Intervention participants interacted repeatedly with the research team and provided generally positive feedback about the Mexfam’s course. It is possible that negative feedback was not given out of politeness or for some other reason. Also, study participants were volunteers and so may have been more inclined to talk about relationships, violence, and sexuality than their non-volunteer peers. Interviews were supplemented with frequent observations of the classrooms and the course, which helped us put the interviews in context in the analysis.

Direct measurement of partner violence would be useful to assess the effects of the program in the medium term, but this brings major conceptual and methodological challenges, which is why for this study we examined the process of violence prevention rather than attempting to measure it directly. As such, this study cannot quantify the effectiveness of the intervention, but rather provides an in-depth exploration of the program’s influence on the factors hypothesized in the theory of change to contribute to the process of violence prevention. This study followed participants for up to three months after the end of the intervention. Longer-term follow-up research could assess whether the shifts in beliefs and behaviors experienced by course participants are sustained over the medium- to long-term, and to what extent the course may contribute to shifting norms not only among course participants, but also within their families and communities. The current findings reflect a comprehensive sexuality education program that intervened only at the individual level rather than at wider social or cultural levels (Marston & King, 2006). It would be useful to assess whether similar interventions that systematically work not only with students, but also with teachers and families, result in intensified program effects.

In conclusion, this paper highlights some mechanisms through which comprehensive sexuality education programming with a gender-transformative approach appears to have supported prevention of and response to intimate partner violence among young people in Mexico City within programmatic timeframes. The findings, which have implications for educational policy, reinforce the importance of schools both as settings for violence and for its prevention. In Mexico, where educational institutions may resist incorporating comprehensive sexuality education, these findings help demonstrate the importance of systematically implementing this type of intervention. The results suggest that this promising and relatively short-term comprehensive sexuality education program has potential for scalability within Mexico’s educational curricula as a strategy to prevent and respond to partner violence and potentially reduce homophobic discrimination or other forms of interpersonal violence common in school settings. We identified programmatic elements that appear most likely to trigger change among participants in Mexico City, which should be tested elsewhere to examine whether or not they can have an impact on beliefs and practices related to intimate partner violence in other settings.

References

Abramsky, T., Watts, C. H., Garcia-Moreno, C., Devries, K., Kiss, L., Ellsberg, M., et al. (2011). What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health, 11(109), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-109.

Arango, D. J., Morton, M., Gennari, F., Kiplesund, S., & Ellsberg, M. (2014). Interventions to prevent and reduce violence against women and girls: A systematic review of reviews (Vol. 10). Washington D.C. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2014/01/20426963/interventions-prevent-or-reduce-violence-against-women-girls-systematic-review-reviews. Accessed 5 Oct 2015.

Barker, G., Aguayo, F., & Correa, P. (2013). Understanding men’s violence against women: Findings from the IMAGES survey in Brazil, Chile and Mexico. Rio de Janeiro. Retrieved from www.promundo.org.br/en. Accessed 16 Jan 2016.

Blanc, A. K., Melnikas, A., Chau, M., & Stoner, M. (2013). A review of the evidence on multi-sectoral interventions to reduce violence against adolescent girls. Retrieved from http://www.girleffect.org/media?id=3013. Accessed 5 Oct 2015.

Blum, R. W., Mmari, K., & Moreau, C. (2017). It begins at 10: How gender expectations shape early adolescence around the world. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4), S3–S4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.07.009.

Breuer, E., Lee, L., De Silva, M., & Lund, C. (2016). Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0422-6.

Chandra-Mouli, V., Gómez Garbero, L., Plesons, M., Lang, I., & Corona Vargas, E. (2018). Evolution and resistance to sexuality education in Mexico. Global Health: Science and Practice, 6(1), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00284.

Chandra-Mouli, V., Plesons, M., Adebayo, E., Amin, A., Avni, M., Kraft, J. M., Lane, C., Brundage, C. L., Kreinin, T., Bosworth, E., Garcia-Moreno, C., & Malarcher, S. (2017). Implications of the global early adolescent study’s formative research findings for action and for research. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4), S5–S9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.07.012.

Cislaghi, B. (2018). The story of the “now-women”: Changing gender norms in rural West Africa. Development in Practice, 28(2), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1420139.

Cislaghi, B., & Heise, L. (2018). Theory and practice of social norms interventions: Eight common pitfalls. Globalization and Health, 14(83), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0398-x.

Dworkin, S. L., Fleming, P. J., & Colvin, C. J. (2015). The promises and limitations of gender-transformative health programming with men: Critical reflections from the field. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 17 Suppl 2(sup2), S128–S143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2015.1035751.

Ellsberg, M., Arango, D. J., Morton, M., Gennari, F., Kiplesund, S., Contreras, M., & Watts, C. (2015). Prevention of violence against women and girls: What does the evidence say? The Lancet, 385(9977), 1555–1566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7.

Farrall, S. (1996). What is qualitative longitudinal research? (Qualitative Series No. 11). Papers in Social Research Methods. London. Retrieved from http://www.lse.ac.uk/methodology/pdf/QualPapers/Stephen-Farrall-Qual Longitudinal Res.pdf. Accessed 1 March 2016.

Flecha, A., Puigvert, L., & Redondo, G. (2005). Socialización preventiva de la violencia de género. Feminismo/S, 6, 107–120.

Fonner, V. A., Armstrong, K. S., Kennedy, C. E., O’Reilly, K. R., & Sweat, M. D. (2014). School based sex education and HIV prevention in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 9(3), e89692. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089692.

Fulu, E., & Kerr-Wilson, A. (2015). What works to prevent violence against women and girls? Evidence review of interventions to prevent violence against women and girls. Retrieved from http://www.whatworks.co.za/resources/all-resources/publications/item/70-global-evidence-reviews-paper-2-interventions-to-prevent-violence-against-women-and-girls. Accessed 6 March 2016.

Gläser, J., & Laudel, G. (2013). Qualitative social life with and without coding: Two methods for early stage data analysis in qualitative research aiming at causal explanations. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.03.006.

Gómez Espinoza, L. M. (2006). El desplazamiento de prácticas impresas y la apropiación de prácticas digitales: Un estudio con alumnos del bachillerato tecnológico aprendiendo a usar la computadora en la escuela. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 11(31), 58–79. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782006000100006.

Grossoehme, D., & Lipstein, E. (2016). Analyzing longitudinal qualitative data: The application of trajectory and recurrent cross-sectional approaches. BMC Research Notes, 9(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-1954-1.

Haberland, N. (2015). The case for addressing gender and power in sexuality and HIV education: A comprehensive review of evaluation studies. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1363/4103115.

Haberland, N., & Rogow, D. (2015). Sexuality education: Emerging trends in evidence and practice. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(1), S15–S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.013.

Heise, L. (2011). What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview. London: STRIVE Research Consortium, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. 978 0 902657 85 2.

Holden, J., Bell, E., & Schauerhammer, V. (2015). We want to learn about good love: Findings from a qualitative study assessing the links between comprehensive sexuality education and violence against women and girls. London. Retrieved from http://www.awid.org/publications/study-we-want-learn-about-good-love. Accessed 19 Feb 2016.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. (2018a). Anuario estadístico y geográfico de los Estadus Unidos Mexicanos 2018. Aguascalientes, Mexico. Retrieved from http://internet.contenidos.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/Productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/nueva_estruc/AEGEUM_2018/702825107000.pdf. Accessed 24 Feb 2019.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. (2018b). Mujeres y Hombres en México 2018. Aguascalientes, Mexico. Retrieved from http://cedoc.inmujeres.gob.mx/documentos_download/MHM_2018.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2019.

Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. (2015). Estudio sobre la Prevención del Embarazo en Adolescentes desde las Masculinidades: Informe final. Cuernavaca. Retrieved from https://backend.aprende.sep.gob.mx/media/uploads/proedit/resources/estudio_sobre_la_pre_9f57284c.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2018.

Jewkes, R., Flood, M., & Lang, J. (2015). From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: A conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1580–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61683-4.

Jewkes, R., Nduna, M., Levin, J., Jama, N., Dunkle, K., Puren, A., & Duvvury, N. (2008). Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 337, a506. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a506.

Kirby, D., Laris, B, & Rolleri, L. (2006). Sex and HIV education programs for youth: Their impact and important characteristics. Retrieved from http://hivhealthclearinghouse.unesco.org/sites/default/files/resources/bie_sex_hiv-education_programs_youth_impact_characteristics_en.pdf.

Kirby, D. B. (2008). The impact of abstinence and comprehensive sex and STD/HIV education programs on adolescent sexual behavior. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 5(3), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2008.5.3.18.

Krug, E. G., Mercy, J. A., Dahlberg, L. L., & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0.

Kyegombe, N., Starmann, E., Devries, K. M., Michau, L., Nakuti, J., Musuya, T., Watts, C., & Heise, L. (2014). “SASA! is the medicine that treats violence”. Qualitative findings on how a community mobilisation intervention to prevent violence against women created change in Kampala, Uganda. Global Health Action, 7, 25082. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.25082.

Marston, C. (2004). Gendered communication among young people in Mexico: Implications for sexual health interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 59(3), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.007.

Marston, C. (2005). What is heterosexual coercion? Interpreting narratives from young people in Mexico City. Sociology of Health & Illness, 27(1), 68–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00432.x.

Marston, C., & King, E. (2006). Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: A systematic review. Lancet, 368, 1581–1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69662-1.

Mejía, M. L., Montoya, P., Blanco, A. J., Mesa, M. L., Moreno, D., & Pacheco, C. I. (2010). Barreras para el acceso de adolescentes y jóvenes a servicios de salud. Retrieved from https://colombia.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/BarrerasJovenesWeb(1).pdf. Accessed 9 April 2018.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Beverly Hills: SAGE Publications.

Miller, D. T., & Prentice, D. (2016). Changing norms to change behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 339–361. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015013.

Montgomery, P., & Knerr, W. (2018). Review of the evidence on sexuality education: Report to inform the update of the UNESCO international technical guidance on sexuality education review of the evidence on sexuality education. Paris. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002646/264649e.pdf. Accessed 13 Nov 2018.

Morrison, A., Ellsberg, M., & Bott, S. (2007). Addressing gender-based violence: A critical review of interventions. The World Bank Research Observer, 22(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkm003.

Nelson, A., Lewy, R., Ricardo, F., Dovydaitis, T., Hunter, A., Mitchell, A., Loe, C., & Kugel, C. (2010). Eliciting behavior change in a US sexual violence and intimate partner violence prevention program through utilization of Freire and discussion facilitation. Health Promotion International, 25(3), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daq024.

Pulerwitz, J., & Barker, G. (2008). Measuring attitudes toward gender norms among young men in Brazil: Development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM scale. Men and Masculinities, 10(3), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X06298778.

Pulerwitz, J., Martin, S., Mehta, M., Castillo, T., Kidanu, A., Verani, F., & Tewolde, S. (2010). Promoting gender equity for HIV and violence prevention: Results from the PEPFAR male norms initiative evaluation in Ethiopia. Washington D.C.: PATH. Retrieved from http://www.hiwot.org.et/Resource/HiwotEthiopiaMNIPoster.pdf. Accessed 6 March 2016.

Report of the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 5–13 September 1994. (1995). Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/docid/4a54bc080.html. Accessed 14 Sep 2018.

Ricardo, C., Eads, M., & Barker, G. (2011). Engaging boys and young men in the prevention of sexual violence. Pretoria, South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.svri.org/menandboys.pdf. Accessed 19 Feb 2016.

Rottach, E., Schuler, S. R., & Hardee, K. (2009). Gender perspectives improve reproductive health outcomes: New evidence. In Population Reference Bureau (Vol. 18, pp. 633–634). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.197906331.

Ruiz, M. Á. B. (2015). Implicaciones del Uso de las Redes Sociales en el Aumento de la Violencia de Género en Adolescentes. Comunicación y Medios, 30, 124–141. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-1529.2014.32375.

Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Santhya, K. G., & Jejeebhoy, S. J. (2015). Sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent girls: Evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Global Public Health, 10(2), 189–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.986169.

Schutt, R. K., & Chambliss, D. F. (2013). Qualitative data analysis. In Making sense of the social world: Methods of investigation (5th ed., pp. 320–357). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs.2011.100352.

Silva, D., De Silva, M. J., Breuer, E., Lee, L., Asher, L., Chowdhary, N., et al. (2014). Theory of change: A theory-driven approach to enhance the Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions. Trials, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-267.

Sinkovics, R. R., & Alfoldi, E. a. (2012). Progressive focusing and trustworthiness in qualitative research: The enabling role of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS). Management International Review, 52(6), 817–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-012-0140-5.

Stake, R. E. (1981). The art of progressive focusing. In Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Los Angeles. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED204358. Accessed 20 Dec 2015.

Starmann, E., Collumbien, M., Kyegombe, N., Devries, K., Michau, L., Musuya, T., Watts, C., & Heise, L. (2017). Exploring couples’ processes of change in the context of SASA!, a violence against women and HIV prevention intervention in Uganda. Prevention Science, 18(2), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0716-6.

Toomey, R. B., McGuire, J. K., & Russell, S. T. (2012). Heteronormativity, school climates, and perceived safety for gender nonconforming peers. Journal of Adolescence, 35(1), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.001.

Tronco Rosas, M. A. (2012). No sólo ciencia y tecnología... Ahora, el IPN a la vanguardia en perspectiva de género. Mexico City. Retrieved from http://www.genero.ipn.mx/Conocenos/Documents/MemoriaPIGPG.pdf. Accessed 13 June 2018.

Tronco Rosas, M. A., & Ocaña López, S. (2012). Género y Amor: Principales aliados de la violencia en las relaciones de pareja que establecen estudiantes del IPN. Mexico City. Retrieved from http://www.genero.ipn.mx/Materiales_Didacticos/Documents/ARTICULO3BCD.pdf. Accessed 5 Sep 2018.

UNFPA. (2015). The evaluation of comprehensive sexuality education programmes: A focus on gender and empowerment outcomes. New York. Retrieved from https://www.unfpa.org/publications/evaluation-comprehensive-sexuality-education-programmes. Accessed 26 July 2015.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2015). UNICEF data: Monitoring the situation and of children and women. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/mexico_statistics.html. Accessed 26 Aug 2018.

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach. Paris. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002607/260770e.pdf. Accessed 7 April 2018.

Verma, R. K., Pulerwitz, J., Mahendra, V. S., Khandekar, S., Singh, A. K., Das, S. S., … Barker, G. (2008). Promoting gender equity as a strategy to reduce HIV risk and gender-based violence among young men in India. Horizons Final Report. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://menengage.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Promoting-Gender-Equity-as-a-Strategy.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2015.

World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/. Accessed 29 July 2015.

Youdell, D. (2005). Sex-gender-sexuality: How sex, gender and sexuality constellations are constituted in secondary schools. Gender and Education, 17(3), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250500145148.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Mexfam Gente Joven health educators for their willingness to participate in the study: Ana Karen Alameda Esquivel, Benjamín Israel Bellazetín Ruíz, Diana Yaret Gutiérrez Cruz, Karla Alejandra Medina Alcántara, Sandra Hernández Ramos, and Viridiana Martínez Valencia. We also thank the School team for allowing us to conduct this research, Mckinley Bleskachek for helping with data collection, and of course, the students and teachers who agreed to spend their time talking to us.

Funding

This study was funded by Mr. Stanley Eisenberg—we thank him for his generosity. We also thank the Advancing Learning and Innovation on Gender Norms (ALIGN) project for their financial support for Shelly Makleff to write this manuscript and for their team’s feedback on prior drafts. The funder did not have any influence on study design, data collection, analysis, or write up.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

SM is a PhD candidate at LSHTM and former staff member and consultant at IPPF/WHR.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Makleff, S., Garduño, J., Zavala, R.I. et al. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Among Young People—a Qualitative Study Examining the Role of Comprehensive Sexuality Education. Sex Res Soc Policy 17, 314–325 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00389-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00389-x