Abstract

Objective

Post-migration stress and trauma impact the way Latino/a immigrants in the USA experience everyday life. Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) reduce stress and strengthen mental health by improving the response to stressors and promoting physical and psychological well-being; however, they have not been tested extensively with Latino/a immigrants in the USA, particularly MBIs implemented online. Thus, more information is needed about the feasibility of online MBIs adapted for Latino/a immigrants.

Method

This study focuses on the feasibility of an online MBI for Latina mothers and community staff members working with them (n = 41). Qualitative (three focus groups) data were collected to assess feasibility, appropriateness, acceptability, and quantitative (questionnaires) data asking about self-reported changes on stress, mindfulness, mind–body connection, subjective well-being, and perceived physical and mental health after the program.

Results

Participants in the three groups indicated the program was appropriate, feasible, and acceptable for Latina immigrant mothers and the staff serving them. Mothers’ and Promotoras’ (community health workers) mean scores for subjective well-being and perceived physical and mental health increased significantly from baseline to post-test. No significant changes were observed in surveys completed by the staff, even though focus group participants reported meaningful improvement.

Conclusion

Overall, the feasibility study was well received and relevant for the organization and the population they serve. The study’s findings provide guidance to others who are implementing online mindfulness practices with Latina immigrants and the staff that work with them.

Preregistration

This study is not preregistered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Migration can be understood as the process of relocating to a new country or city in search of safety or better opportunities. In the USA, one in three Latinos is an immigrant (Passel & Cohn, 2008). Immigration is linked to high stressors and unique traumas that may impact the way people experience their everyday life and difficult situations (Nagy et al., 2022). A large proportion of Latinx immigrants, especially those coming from Central America, are fleeing potentially traumatic circumstances such as extreme poverty, government corruption, deprivation, inequality, and violence (Chavez et al., 2022; Kaltman et al., 2011; Peña-Sullivan, 2020).

Post-immigration stress is a robust predictor of poor mental health outcomes, psychological distress, and diminished well-being (Barton et al., 2022), and influences how people tackle daily stressors (Peña-Sullivan, 2020). Post-immigration stressors include living in dangerous neighborhoods, adverse working and living conditions, lack of employment and/or health benefits, and acculturation stress (psychological adjustment to a new culture) (Balidemaj & Small, 2019). The way an individual experiences stress can directly impact neurological and other biological processes in the body. A person with a previous history of trauma may react to low-stress situations with the same intensity as in high-stress situations (Miller et al., 2019).

Practices such as mindfulness, which fosters connection to the present moment, kindness for self and others (Kearney et al., 2021), and connection with emotions in the body (Kabat-Zinn & Hanh, 1990) can help to overcome trauma-related negative effects such as dissociation, heightened irritability, and an overactive nervous system. Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been shown to decrease stress and improve health outcomes in underrepresented populations. Research on mindfulness in Latinx populations has shown reductions in smoking (Spears et al., 2015) and depression (Lopez-Maya et al., 2019), and greater psychological well-being (Edwards et al., 2014; Roth & Robbins, 2004).

A vast body of research shows the advantages and effectiveness of using online platforms as channels for delivering mental health interventions (Andersson et al., 2019; Spijkerman et al., 2016), including lower costs and higher reach by decreasing access barriers such as lack of health insurance, childcare, or transportation. Meanwhile, barriers to the uptake of online MBIs include people’s preference for face-to-face interventions (Apolinario-Hagen et al., 2017), high attrition rates, and low adherence, especially for unguided formats (Fleming et al., 2022). While a small yet growing body of evidence shows the benefits of MBIs in Latinx populations, existing research often reflects a lack of a community participatory approach to culturally adapt MBIs (Cotter & Jones, 2020), and there is little attention paid to access and participation barriers, such as lack of interest, lack of access to care, lack of transportation, lack of childcare, and other competing family demands (Roth & Robbins, 2004).

Implementation research for evidence-based programs seeks to understand the barriers and facilitators to implement these programs in real-world settings. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) is a well-recognized framework for exploring implementation constructs such as feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness, and fidelity, which contribute to the barriers and facilitators of integrating interventions to real-life practice (Keith et al., 2017). CFIR has been previously applied in the context of telemedicine (Batsis et al., 2020; Stevenson et al., 2018) to understand barriers and facilitators to implement prevention programs with hard-to-reach and vulnerable populations.

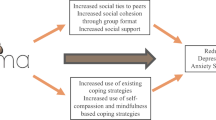

The purpose of this study was to apply CFIR to test and refine an adapted MBI for Latinas and the staff that work with them in a community setting. The study aimed to inform the future implementation and long-term success of the program through its results. The Yo Soy Paz program was an online, synchronous, 1 h–per–week group-based program delivered over 8 weeks. This study used a mixed-methods methodology to examine the acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of the program and to assess preliminary evidence of changes in levels of stress, overall physical and mental health, mindfulness, mind–body connection, and subjective well-being in mothers and staff participating in the program. We hypothesized that the program demonstrates strong appropriateness, feasibility, and acceptability and that the participants of the Yo Soy Paz program report descriptively lower stress levels and better self-rated overall physical and mental health, as well as higher mindfulness, mind–body connection, and subjective well-being levels at the end of the program compared to before participating in the program.

Method

Participants

Study data came from 41 participants: staff (n = 18), Promotoras (immigrant mothers trained as community workers) (n = 7), and immigrant mothers (n = 16) delivering and/or receiving services from a community organization. The organization in Maryland provides school- and community-based positive youth development services with youth and their families. Parent outreach workers/case managers also assess family needs and develop action plans to connect families to needed resources.

The eligibility criteria to participate in the study were the following: (a) being 18 years of age or older, (b) fluency in Spanish, (c) receiving or delivering services at the community organization, and (d) self-identified as Latinx, if part of the Promotoras’ or mothers’ groups. Non-Latino staff members fluent in Spanish were allowed to participate because of (1) their familiarity with the people they served, (2) their close personal relationships with this population (i.e., second-generation Latinx or had Latinx family members), (3) second-hand trauma that they were exposed to in their work (Akinsulure-Smith et al., 2018), and (4) a request from the organization to address the mental health and stress reduction needs of the staff. Nearly 90% of the participating staff self-identified as Latinx, and close to 70% had immigrated to the USA and are facing similar stressors as the population they served. Participant demographics are shown in Table 1.

Procedure

The intervention components are outlined in Table 2. The original intervention was created by Jon Kabat-Zinn to train chronic pain patients in self-regulation (Kabat-Zinn, 1982). The intervention was adapted using a coordinated and systematically guided process based on the ADAPT-ITT framework (Wingood & DiClemente, 2008) (ADAPT-ITT steps can be found in Appendix A). Each weekly session included two mindfulness exercises, reflection questions, open-access videos, PowerPoint slides, and life examples.

The program and all sessions except yoga were led in Spanish by a facilitator, a Latina psychologist with over 10 years of mindfulness experience. The yoga session was taught by a Latina yoga instructor. The intervention engaged with the participants as agents of strength and resilience while respecting their own processes through certain traumatic experiences. The facilitator of the classes was aware of this approach and provided a safe environment to debrief after the exercises to discuss any triggering circumstances and allow participants to share their feelings and thoughts (Reeves, 2015). There was not a minimum of participants required for each lesson.

Survey and demographic data were collected at study entry in March 2021, and self-report attendance data were collected in May 2021 for a total of 38 respondents of the 41 participants at baseline (92.6%), and 28 respondents at post-intervention (68.2%). The study flowchart is presented in Fig. 1. Attendance was taken in every class using a short Qualtrics questionnaire at the start of each class, on which participants entered IDs they had earlier created. Since not every participant completed the questionnaires, remembered the ID they had created, or created different IDs for each of the forms they were asked to complete, participants were also asked in post-questionnaires to indicate the classes they attended. At week eight, 11 of the 15 staff (73%) participating in the intervention also completed a post-intervention questionnaire via Qualtrics to assess acceptability, feasibility, appropriateness, and inner and outer setting of the intervention.

The three MBI groups (Spanish-speaking staff, Promotoras, and mothers) were recruited through the community organization. Staff members received emails inviting them to participate in the program along with the informed consent information and the link to the baseline assessment to be completed prior to the first session. Promotoras and mothers who were part of weekly education and support groups were verbally consented by the group leaders. After providing consent, Promotoras received the link to a Qualtrics survey to be completed prior to the first session. Due to literacy barriers for those in the mothers’ group, the organization’s group leader conducted the baseline questionnaires individually via phone in Spanish.

All documents were provided in Spanish. Like the baseline questionnaires, post-intervention questionnaires were conducted online via Qualtrics survey for the staff and the Promotora groups, and over the phone for the mothers’ groups. On week eight of the program, the first author conducted focus groups in Spanish with each of the three groups of participants. Due to budgetary constraints, only the Promotoras and mothers received a $20 gift card for their participation. The three 1-hr-long focus groups (FGs) with n = 11 staff, n = 9 Promotoras, and n = 10 mothers were audio-recorded and transcribed. In the Promotora group, two of the participating members were staff who received the intervention along with the Promotoras; 73% of the participants participated in a focus group. Focus groups were conducted via Zoom in Spanish by the first author, a native speaker, using the interview guide developed by the research team. All focus groups were analyzed in their original language.

Measures

To assess implementation results, we used CFIR’s five major domains (intervention characteristics, inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals, and implementation process) and the ten relevant subcategories for this study to develop two semi-structured focus group guides for staff and Promotoras/mothers. Participants were asked about their satisfaction with the program, program benefits, interest in the content, and use of skills outside the program. Focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim to be analyzed in their original language. Additionally, we included items to capture appropriateness, acceptability, feasibility, and inner and outer setting, which are detailed in Table 3.

Scales for acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility were comprised of four items measured on a 5-point scale from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree. Acceptability was assessed with the Acceptability of Intervention Measure (AIM) scale (Weiner et al., 2017), rating the organization’s receptivity of the intervention, the participant attendance, and the comments about the intervention characteristics, such as its design and quality, complexity, and the participants’ beliefs about the intervention. Appropriateness was assessed using the Intervention Appropriateness Measure (IAM) scale (Weiner et al., 2017), rating the intervention’s fit with the organization’s vision and mission, its appropriateness to match the clients’ needs, and comments about the inner setting’s compatibility and outer setting’s clients’ needs and resources and tension for change. Feasibility was assessed with the Feasibility of Intervention Measure (FIM) scale (Weiner et al., 2017) and comments about the intervention’s characteristics regarding adaptability and cost. Inner and outer settings were measured with three items on a 5-point scale, assessing receptivity, alignment, and ability to meet client needs (1 = low to 5 = high).

Fidelity

We assessed fidelity with weekly fidelity checklists completed by the instructor and the first author who observed all of the sessions. A summative score was created for each of the lessons and then converted into a percentage. For lectures where the facilitator and the PI marked all the activities as complete, there was 100% fidelity. The first author also kept a log of barriers and facilitators for each lesson. Process implementation comments were also captured from the barriers and facilitators section of the focus groups.

Perceived Stress

We used the Short-form Perceived Scale Stress Scale (PSS), a 4-item measure of the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful (Cohen et al., 1983), with a 5-point response scale (0 = never to 5 = always). Two items were reversed coded so that a high number equates to higher levels of perceived stress. We calculated the α at pre (α = 0.793) and post (α = 0.635) which is similar to the α calculated in other studies with Spanish-speaking populations of α = 0.74 (Vallejo et al., 2018).

Perceived Overall Physical and Mental Health

We used two questions to assess this measure: How would you rate your overall physical health? How would you rate your overall mental health? The questions were asked on a Likert-type scale from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent. This measurement has been used in several studies, and its reliability is acceptable, although it has not been tested with Latino populations (Bombak, 2013).

Mind–Body Connection

The Scale of Body Connection (SBC) (Price et al., 2017) (α = 0.666 at pre-test and α = 0.807 at post-test) consisted of 20 self-report items about two distinct dimensions of the mind–body connection: body awareness (BA) and bodily dissociation (BD). Items were on a 5-point Likert-type scale measuring current experiences, ranging from 1 = never to 5 = all the time. Two questions were removed following the advice of the community partners (aware during sexual activity and separated during sexual activity).

Mindfulness-Acting with Awareness

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) (Osman et al., 2016) is a 15-item scale designed to assess the short-term or current expression of a core characteristic of mindfulness. We used a short version of the MAAS scale made up of five questions with response choices ranging from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much. We calculated the overall α at pre (α = 0.76) and post (α = 0.87). The long version of the scale has been validated in Spanish and has shown equivalent factor analysis as the English version (Johnson et al., 2013). This measure only captures the dimension of mindfulness that focuses on acting with awareness. It does not capture other important aspects of mindfulness such as observing, describing, nonreacting, and non-judging (Baer et al., 2006; Grossman, 2011).

Subjective Well-Being

The Mental Health Continuum short form (MHC-SF) had 14 items. Response options were based on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = never to 6 = every day (Keyes et al., 2008). We calculated the overall α at pre-test (α = 0.69) and post-test (α = 0.75), which were smaller than the alphas calculated by the scale creators at α = 0.91 and of the validated Spanish version of α = 0.94 (Echeverria et al., 2017).

Data Analyses

For the focus groups, the research team reviewed the transcripts for accuracy prior to analysis. Qualitative data were analyzed in Dedoose using Template Analysis (Crabtree & Miller, 1992). First, we prepared a codebook that was organized by anticipated themes using the CFIR as a framework. Second, two coders who are native Spanish speakers (JMB and JB) coded each transcript line by line, refining the codebook as needed. After the first round of coding, the codebook was refined with additional codes discussed by the two coders and transcripts were recoded with the additional codes. Finally, we compiled final themes and subthemes, and quotes were translated into English.

We ran descriptive statistics to assess the demographics of the group. A self-created ID number linked the baseline questionnaire (n = 38) to the post-intervention questionnaire (n = 28). Means were calculated for all scale items. Higher scores represent a more desired level of the attribute measured. Internal consistency reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha for all the scales at baseline and post-test. We also reviewed the data for missing values. We calculated the mean from available items if a respondent was missing one question from the scale. This was done for two participants for the Flourishing scale who were missing one item and five participants for the Mind–Body scale who were missing an item. All other data were complete. We ran one-sample t tests to assess the direction of changes in mean scores of perceived stress, flourishing, mindfulness, and mind–body connection from baseline to post-test.

Results

Out of the 28 respondents that completed the post-questionnaire, 85% (n = 24) indicated they attended five or more classes. Fifty percent (n = 16) indicated attending all seven classes. Some of the staff missed a class due to competing demands. The most inconsistent group was the mothers’ group since most of the mothers participated in the class while also taking care of other tasks such as being at work or doing house chores (e.g., babysitting, cleaning a house, picking up children). This was also noted through the participation in the virtual focus groups.

All sessions except session 2 had 100% fidelity completion. Session 2—connecting with my [migration] story, had 75% fidelity completion. In this session, participants spent most of the time answering the opening question: What was your reason for migrating? The instructor spent some time processing the stories from the participants since most had traumatic elements, such as fleeing violence, fleeing deprivation, and leaving friends and family behind, and thus there was no time for the final meditation. During this lesson, participants experienced difficult emotions that had to be addressed during the session.

In some classes, the internet dropped while an important discussion was taking place. It was useful to have two co-hosts; if one of the hosts lost internet connectivity, the participants were able to remain online while connectivity was regained. Some mothers participated while driving, running errands, taking care of children, or working. This multitasking prevented them from fully engaging with the class content and the practice exercises. Some meditations used at the end of the lessons were long and participants lost focus. The facilitator found that guided meditations under 8 min worked best for the online environment. Participants also responded better when the meditation was led by the facilitator rather than through a video. During the Connecting with Difficult Emotions lesson and meditation, mother participants shared connecting with feelings of deep sadness. Some mothers reflected on the possibility of needing additional help to cope with these emotions. One mother was connected to a psychologist after sharing her experience of not being able to enjoy everyday life and having difficulty getting out of bed. She mentioned it was the first time she had realized she had difficult emotions she had not been able to identify.

Acceptability (M = 4.70, SD = 0.45), appropriateness (M = 4.61, SD = 0.49), and feasibility (M = 4.56, SD = 0.50) rated high, and inner and outer settings rated in the mid-range (M = 3.69, SD = 0.48) (Table 3). Template analysis of qualitative focus group data resulted in three themes—acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness—and six subthemes—perceived benefits, interest in content, feasibility of continuing implementing the program, adaptations, use of skills outside the program, and fit with the organization’s demands, as described below.

Acceptability

Perceived Benefits

Nearly all participants reported that they benefited from receiving the program and that they found the content interesting, specially learning about the stress response and how to manage difficult emotions. Their comments ranged from becoming aware of the present moment, learning the benefits of slowing down to live more intentionally, and becoming aware of the benefits of mindfulness for relaxation and for taking care of their emotional health. One Promotora shared:

“That [awareness of the present moment] has gotten stuck with me every morning, I take my coffee, I don’t work, I stop doing everything and it has worked well. I enjoy my morning coffee in peace.”

Staff also found their program useful to share with other coworkers and to navigate their emotions. One staff member commented:

“We all have our own problems and if it wasn’t for this space of being able to say ‘Oh, [co-worker’s name] is also going through this. So, for us, it is a moment where we can be together and learn about methods on how to navigate our emotions.”

Interest in content. In terms of the migration story, mothers and Promotoras really enjoyed having a space to dig deeper about this important moment in their lives. One mother shared:

“Even though it is sad to remember (our migration story), everything we have been through, it is very nice to remember what we have been through, what we are currently living, and how we are moving forward in life [...] When you are about to give up, someone shows up and gives you a hand.”

Some mothers and Promotoras mentioned struggling with practicing yoga, meditation, or accepting quotes, videos, or stories that made references to other religions since they were taught in their home countries by family members or religious leaders that such practices were negative. One mother commented: “I respect other beliefs, but I only believe in one God, Jesus Christ, and that was a barrier for me, because I don’t approve of following other traditions.”

Additional feedback received from the participants has been compiled in Table 4.

Feasibility

Implementing the Program

Staff members reflected on the possibility of implementing the program, or parts of the program, with their clients. For the most part, the staff felt comfortable implementing the program in the future with proper/additional training (Table 4).

In terms of delivering the class online, the focus groups discussed advantages and disadvantages. One of the biggest disadvantages noted by the staff and commented by mothers was lack of a quiet space in which to practice the meditations and exercises. As noted by one of the group leaders, getting mothers to participate was also more difficult. To address this, a staff member recommended calling mothers by their names and rotating who gets to share in each of the sessions. Staff also shared that online delivery made it difficult to help mothers with literacy barriers for activities that required writing. Staff also reported that mothers had multiple distractions while taking the program online, and having in-person practices would help alleviate this issue. Nevertheless, mothers reported enjoying the online format since it reduced transportation time and allowed them more flexibility with their schedule, since they could watch their children and make dinner while listening to the class.

Suggested Adaptations to the Program

Staff talked about setting attention protocols in case some of the exercises or topics triggered a participant. They mentioned the possibility of including a second facilitator that could help triggered participants one on one in a breakout room. To help participants feel comfortable sharing difficult emotions, one staff member also recommended adding tools to strengthen communication and self-esteem. Finally, staff members recommended not talking about different religions to the mothers. As a solution, they proposed including quotes without the authors or including more neutral quotes and content.

While having a mindfulness program in Spanish was seen as a great advantage, one staff member recommended having culturally and linguistically appropriate meditations, since most of the meditations that were included were from people from Spain and not from people from Central or South America. Another staff member recommended adding components to the program when implementing it with youth, such as incorporating an artistic component to help youth express their feelings.

Appropriateness

Practical Application of Learned Skills

Most of the participants talked about their experience using the exercises learned in class to foster relaxation and manage difficult emotions outside of the program, especially in personal relationships or painful situations. One Promotora shared:

“When I am in a situation where a person is talking and I am uncomfortable, I try to focus on my body, and I say ‘well, this is how I am feeling’. So I start doing the exercises you taught us, I start breathing and I start doing certain things so that I can control the situation and not the other way around.”

Additional quotes can be found in Table 4.

Fit with Organization’s Mission and Vision

Staff shared how they had been using the tools that they had learned from the program to help and to better understand their clients. One staff member specifically cited mindfulness as a useful tool to help clients deal with the stress and anxiety from daily life. Since participating, staff mentioned using the activities or videos from the program with their clients.

They also commented on the usefulness of the program as a mental health promotional tool at the community and individual level. Staff members mentioned the importance of helping their clients cultivate awareness of the present moment to improve their results and participation in other programs offered by the organization.

Staff from the focus groups reported the importance of mental health promotional programs for their already vulnerable clients whose mental health needs increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They mentioned having similar initiatives such as community mental health programs to offer spaces where healing can occur due to the rising demand for these services (Table 4).

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

As shown in Table 5 of the Supplementary Materials, staff reported an increase in overall physical health, overall mental health, subjective well-being, and perceived stress, but also reported lower-body dissociation and lower-body awareness. However, none of the mean differences were statistically significant. For the mothers’ and Promotoras’ groups, participants reported significant increases in subjective well-being (t = 3.24, p = 0.006), perceived physical health (t = 3.59, p = 0.003), and perceived mental health (t = 4.18, p < 0.001). Body awareness increased and body dissociation decreased, but the change was non-significant.

Discussion

The project evaluated the acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of an adapted MBI for immigrant Latina mothers and the staff workers who work with them as well as changes in self-reported health outcomes. Overall, the study was well received and considered relevant for the organization and the population they serve. Focus group results, pre-post survey data, attendance logs, and the fidelity checklists provided insights on successes and areas for improvement.

In terms of health outcomes, we noted reduction in stress levels among the Promotoras’ and mothers’ groups. All three groups reported an improvement in their overall perceived physical and mental health and subjective well-being, though changes in these outcomes were not significant for the staff. The qualitative findings also suggested that this program was beneficial for mental, emotional, and physical health. The findings are consistent with other mindfulness-based stress reduction programs regarding participant’s improvement in mental health and ability to relax, to cope with daily stressors by living in the present moment, and to foster self-kindness. Participants from our study cited improvement in family dynamics and their ability to recognize and manage difficult emotions, similar to other programs (Castellanos et al., 2020; Cotter & Jones, 2020; Ryan et al., 2018; Tobin et al., 2021).

Participants’ accounts of acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of the program were evident for all three groups of participants. Most staff members, Promotoras, and mothers reported valuing and utilizing the skills learned throughout the program outside of the lessons’ time. Staff also reported using the exercises in their personal as well as their professional lives. Qualitatively, most participants reported benefits from participation and enjoying opportunities to learn from and share with one another. This program made them feel less alone and, in the case of the mothers and Promotoras, less guilty for experiencing certain feelings.

During the sessions, primarily the “connecting with my [migration] story,” participants shared prior traumatic events from their pre-migration and migration experiences, highlighting the need for using a trauma-informed and trauma-based approach when working with this population (Nagy et al., 2022). Even though the migration topic discussion was challenging for the staff members, the mothers and Promotoras reported the greatest benefit from this topic. We recommend moving this section to a later week of the curriculum, allowing for two sessions, or providing longer sessions and creating spaces for the mothers to process their emotions, and avoiding triggering questions such as “What were your reasons for migration?” and instead focusing on what they have learned and how they have grown since they migrated to the new country.

Trauma-informed care (TIC), which is based on the knowledge and understanding of trauma and its far-reaching implications (SAMHSA, 2014), has been broadly recognized as an effective framework for working with immigrant Latinx youth and their families (Jolie et al., 2021). In a strengths-based—rather than a deficits-based—approach, TIC can draw from personal and community strengths, to allow for growth and healing after experiencing trauma through trusting environments that actively avoid revictimization (Miller et al., 2019). It has been highlighted by a recent call to action for the mindfulness field to develop and focus on a stronger strength-based and community practice approach when developing and delivering MBIs for the Latinx population (Nagy et al., 2022).

All groups seemed to benefit from learning about the impact of chronic stress and trauma and the tools to counteract it. Some participants reported the surfacing of difficult emotions connected to previous life events after practicing mindfulness, which is suggestive of being fully engaged in the practice. It is a common result from practicing mindfulness that unidentified emotions may surface, and with the appropriate guidance, mindfulness can increase acceptance of emotions and contribute to improved self-awareness and growth (van der Kolk, 1994). Nevertheless, to increase the appropriateness of MBIs with Latinx, experts have noted the importance of doing no harm through these interventions since some practices can be triggering and resurface past trauma (Baer et al., 2019; Van Dam et al., 2018). Additionally, previous research has found that the most successful MBIs are led by experienced facilitators with a mindfulness practice of their own (Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Kabat-Zinn & Hanh, 1990; McKeering & Hwang, 2019; Palacios et al., 2022) and where participants feel they are being supported by the instructor (Apolinario-Hagen et al., 2017). Therefore, it is recommended that the curriculum is delivered by someone with an extensive background and experience on mindfulness and/or psychology, and who understands the culture and background of the population that is being served.

This intervention was delivered online during the period of COVID-19 restrictions. Factors that helped this program achieve success online were (1) the strong, pre-existing relationship with the community organization including the staff, Promotoras, and mothers which fostered trust and open communication; (2) the cultural adaptation of the program through a community-based participatory research approach; and (3) the inclusion of a knowledgeable Latina psychologist/mindfulness instructor who was able to deliver the classes in Spanish. The facilitator reinforced this trusting environment by answering questions as needed, providing guidance if staff members were dealing with a particular situation with a client, and helping participants process difficult situations and emotions. The information was culturally sensitive, and it was adapted to avoid re-traumatization and to recognize the effects of trauma in the body (Miller et al., 2019). While there is a growing interest in mind–body health, critical research featuring minorities’ perspectives and experiences is rare. Incorporating topics such as cultural humility while developing and implementing MBIs with Latinx immigrant populations is imperative for future research (Fleming et al., 2018, 2022; Nagy et al., 2022).

Moreover, acknowledging and addressing the needs of the focus population within the different levels of the socio-ecological model are also important when implementing these types of programs. In other words, MBIs should be complementary to other programs and not the sole focus. Staff members did highlight an increasing tension for change to offer more promotional mental health programs, for youth and their families to help clients cope with strong emotions and stress and deal with the shortage of therapists that the organization is currently facing. Though recruiting the organization’s staff as participants was not an original objective of the program, it became clear that MBIs could be useful for both staff and clients. This is an innovative approach since MBIs focusing on Latinx immigrant populations seldom include the staff that works with them.

Limitations and Future Research

The study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic while restrictions for in-person gatherings were in place and unique stressors were present. The implementation of the study could vary in a context where people are more free to meet in-person. The response rate at post-intervention (61.4%) was not as high as expected. The positive results of the intervention could have been overrepresented as we only capture the responses of people who participated actively in the program.

Finally, following a request from the community organization to avoid over-burdening participants with questions, the scales that were used for the most part were the shorter versions of the original scales. We did not include other similar scales to conduct further psychometric analysis to test for reliability and validity of the scales with this population. It is also important to mention that there are serious concerns about the ability of the MAAS instrument to measure all the dimensions of mindfulness (Grossman, 2011; Van Dam et al., 2011). Future research should aim to measure mindfulness as a multi-dimensional construct made up by different facets: observing, describing, acting with awareness, nonreacting, and non-judging (Baer et al., 2006), rather than a unidimensional construct, as it is measured by MAAS. We tried to address this limitation by including both qualitative and quantitative data collection and by providing a trusting environment for participants to share their feelings. Future questionnaires could also include trauma, depression, minority stress, and PTSD measures to fully understand program effects. Future programs could benefit from adding a follow-up assessment and including physiological stress markers in addition to self-reported data.

This study contributes to the understanding of implementing MBIs with immigrant Latinx populations and the staff that works with them. A community-based approach was imperative for the success of the program as well as incorporating TIC through the community organization that was hosting the program. Given that some participants reported the surfacing of difficult emotions or connecting difficult emotions with a previous event in their life as a result of practicing a mindfulness exercise, it is important that future studies address adverse effects of MBIs in vulnerable populations and provide guidelines on how to best protect participants during these practices (Baer et al., 2019; Van Dam et al., 2018).

Rarely do studies of MBIs with Latinx populations have incorporated the topic of trauma (Cotter & Jones, 2020). More studies are needed to understand the impact of MBIs with immigrant populations that have been exposed to trauma and second-hand trauma and who currently face immigration stressors. While there is a growing interest in mind–body health, critical research featuring minorities’ perspectives and experiences is rare (Fleming et al., 2022). Future studies should aim to include a participatory approach that includes the experiences and perspectives of the focus population.

Data Availability

All data are available at the Open Science Framework, https://rb.gy/vd5k8r.

References

Akinsulure-Smith, A. M., Espinosa, A., Chu, T., & Hallock, R. (2018). Secondary traumatic stress and burnout among refugee resettlement workers: The role of coping and emotional intelligence. Journal of Trauma and Stress, 31(2), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22279

Andersson, G., Titov, N., Dear, B. F., Rozental, A., & Carlbring, P. (2019). Internet-delivered psychological treatments: From innovation to implementation. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20610

Apolinario-Hagen, J., Kemper, J., & Sturmer, C. (2017). Public acceptability of e-mental health treatment services for psychological problems: A scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 4(2), e10. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.6186

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

Baer, R. A., Crane, C., Miller, E., & Kuyken, W. (2019). Doing no harm in mindfulness-based programs: Conceptual issues and empirical findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 71, 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.01.001

Balidemaj, A., & Small, M. (2019). The effects of ethnic identity and acculturation in mental health of immigrants: A literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 65(7–8), 643–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019867994

Barton, A., Novoa, O., Sanchez, M., Romano, E., & Cano, M. (2022). Impact of pre-migration assets and pre-migration trauma on acculturative stress among recent Latinx immigrant young adults. Ethnicity & Health, 27(6), 1410–1427. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2021.1881766

Batsis, J. A., McClure, A. C., Weintraub, A. B., Sette, D., Rotenberg, S., Stevens, C. J., Gilbert-Diamond, D., Kotz, D. F., Bartels, S. J., Cook, S. B., & Rothstein, R. I. (2020). Barriers and facilitators in implementing a pilot, pragmatic, telemedicine-delivered healthy lifestyle program for obesity management in a rural, academic obesity clinic. Implementation Science Communication, 1, 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-020-00075-9

Bombak, A. E. (2013). Self-rated health and public health: A critical perspective. Frontiers in Public Health, 1, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2013.00015

Castellanos, R., Spinel, M. Y., Phan, V., Orengo-Aguayo, R., Humphreys, K. L., & Flory, K. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis of cultural adaptations of mindfulness-based interventions for Hispanic populations. Mindfulness, 11(2), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01210-x

Chavez, F. L., Gonzales-Backen, M. A., & Perez Rueda, A. M. (2022). International migration, work, and cultural values: A mixed-method exploration among Latino adolescents in US agriculture. Family Relations, 71(1), 325–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12603

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Cotter, E. W., & Jones, N. (2020). A review of Latino/Latinx participants in mindfulness-based intervention research. Mindfulness, 11(3), 529–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01266-9

Crabtree, B. F., & Miller, W. F. (1992). A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In B. F. Crabtree & W. L. Miller (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (pp. 93–109). Sage.

Echeverria, G., Torres, M., Pedrals, N., Padilla, O., Rigotti, A., & Bitran, M. (2017). Validation of a Spanish version of the mental health continuum-short form questionnaire. Psicothema, 29(1), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.3

Edwards, M., Adams, E. M., Waldo, M., Hadfield, O. D., & Biegel, G. M. (2014). Effects of a mindfulness group on Latino adolescent students: Examining levels of perceived stress, mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological symptoms. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 39, 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2014.891683

Fleming, T., Bavin, L., Lucassen, M., Stasiak, K., Hopkins, S., & Merry, S. (2018). Beyond the trial: Systematic review of real-world uptake and engagement with digital self-help interventions for depression, low mood, or anxiety. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(6), e199. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9275

Fleming, C. M., Womack, V. Y., & Proulx, J. (2022). Beyond white mindfulness: Critical perspectives on racism, well-being and liberation. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003090922

Grossman P. (2011). Defining mindfulness by how poorly I think I pay attention during everyday awareness and other intractable problems for psychology's (re)invention of mindfulness: comment on Brown et al. (2011). Psychological Assessment, 23(4), 1034–1046.https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022713

Johnson, C. J., Wiebe, J. S., & Morera, O. F. (2013). The Spanish version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS): Measurement invariance and psychometric properties. Mindfulness, 5, 552–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0210-1

Jolie, S. A., Onyeka, O. C., Torres, S., DiClemente, C., Richards, M., & Santiago, C. D. (2021). Violence, place, and strengthened space: A review of immigration stress, violence exposure, and intervention for immigrant Latinx youth and families. Annual Reviews in Clinical Psychology, 17, 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-100217

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Kabat-Zinn, J., & Hanh, T. N. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte.

Kaltman, S., Hurtado de Mendoza, A., Gonzales, F. A., Serrano, A., & Guarnaccia, P. J. (2011). Contextualizing the trauma experience of women immigrants from Central America, South America, and Mexico. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(6), 635–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20698

Kearney, D. J., Malte, C. A., Storms, M., & Simpson, T. L. (2021). Loving-kindness meditation vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 4(4), e216604. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6604

Keith, R. E., Crosson, J. C., O’Malley, A. S., Cromp, D., & Taylor, E. F. (2017). Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: A rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implementation Science, 12(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0550-7

Keyes, C. L., Wissing, M., Potgieter, J. P., Temane, M., Kruger, A., & van Rooy, S. (2008). Evaluation of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF) in setswana-speaking South Africans. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 15(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.572

Lopez-Maya, E., Olmstead, R., & Irwin, M. R. (2019). Mindfulness meditation and improvement in depressive symptoms among Spanish- and English speaking adults: A randomized, controlled, comparative efficacy trial. PLoS ONE, 14(7), e0219425. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219425

McKeering, P., & Hwang, Y.-S. (2019). A systematic review of mindfulness-based school interventions with early adolescents. Mindfulness, 10, 593–610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0998-9

Miller, K. K., Brown, C. R., Shramko, M., & Svetaz, M. V. (2019). Applying trauma-informed practices to the care of refugee and immigrant youth: 10 clinical pearls. Children (Basel), 6(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/children6080094

Nagy, G. A., Cuervo, C., Ramos Rodriguez, E. Y., Plumb Vilardaga, J., Zerubavel, N., West, J. L., Falick, M. C., & Parra, D. C. (2022). Building a more diverse and inclusive science: Mindfulness-based approaches for Latinx individuals. Mindfulness, 13(4), 942–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01846-2

Osman, A., Lamis, D. A., Bagge, C. L., Freedenthal, S., & Barnes, S. M. (2016). The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale: Further examination of dimensionality, reliability, and concurrent validity estimates. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(2), 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1095761

Palacios, A. M., Bender, S. L., & Berry, D. J. (2022). Characteristics of mindfulness-based interventions in schools: A systematic review in school psychology journals. Contemporary School Psychology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-022-00432-6

Passel, J. S., & & Cohn, D. (2008). US population projections: 2005–2050. Accessed February 02, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050/

Peña-Sullivan, L. (2020). The “wrong kind” of immigrants: Pre-migration trauma and acculturative stress among the undocumented Latinx community. Clinical Social Work Journal, 48, 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-019-00741-z

Price, C. J., Thompson, E. A., & Cheng, S. C. (2017). Scale of body connection: A multi-sample construct validation study. PLoS ONE, 12(10), e0184757. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184757

Reeves, E. (2015). A synthesis of the literature on trauma-informed care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(9), 698–709. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1025319

Roth, B., & Robbins, D. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health-related quality of life: Findings from a bilingual inner-city patient population. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(1), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000097337.00754.09

Ryan, D., Maurer, S., Lengua, L., Duran, B., & Ornelas, I. J. (2018). Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma (ALMA): An evaluation of a mindfulness intervention to promote mental health among Latina immigrant mothers. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research, 45(2), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-017-9582-7

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD.

Spears, C. A., Houchins, S. C., Stewart, D. W., Chen, M., Correa-Fernandez, V., Cano, M. A., Heppner, W. L., Vidrine, J. I., & Wetter, D. W. (2015). Nonjudging facet of mindfulness predicts enhanced smoking cessation in Hispanics. Psychology of Addictive Behavior, 29(4), 918–923. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000087

Spijkerman, M. P., Pots, W. T., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: A review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.009

Stevenson, L., Ball, S., Haverhals, L. M., Aron, D. C., & Lowery, J. (2018). Evaluation of a national telemedicine initiative in the Veterans Health Administration: Factors associated with successful implementation. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 24(3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16677676

Tobin, J., Hardy, J., Calanche, M. L., Gonzalez, K. D., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., Contreras, R., & Bluthenthal, R. N. (2021). A community-based mindfulness intervention among Latino adolescents and their parents: A qualitative feasibility and acceptability study. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23(2), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-00985-9

Vallejo, M. A., Vallejo-Slocker, L., Fernandez-Abascal, E. G., & Mananes, G. (2018). Determining factors for stress perception assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) in Spanish and other European samples. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 37. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00037

Van Dam, N. T., Sheppard, S. C., Forsyth, J. P., & Earleywine, M. (2011). Self-compassion is a better predictor than mindfulness of symptom severity and quality of life in mixed anxiety and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(1), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.011

Van Dam, N. T., van Vugt, M. K., Vago, D. R., Schmalzl, L., Saron, C. D., Olendzki, A., Meissner, T., Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Gorchov, J., Fox, K. C. R., Field, B. A., Britton, W. B., Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A., & Meyer, D. E. (2018). Mind the hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspectives of Psychological Sciences, 13(1), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617709589

van der Kolk, B. A. (1994). The body keeps the score: memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 1(5), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229409017088

Weiner, B. J., Lewis, C. C., Stanick, C., Powell, B. J., Dorsey, C. N., Clary, A. S., Boynton, M. H., & Halko, H. (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implemention Science, 12(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3

Wingood, G. M., & DiClemente, R. J. (2008). The ADAPT-ITT model: A novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV Interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 47(Suppl 1), S40–S46. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Identity INC. for their collaboration and support throughout the program and data collection. We are grateful to Manuela Muñoz for facilitating the program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Juliana Muñoz B: conceptualization, methodology, curriculum development, data analysis, writing—original draft preparation; Diana Parra: conceptualization, curriculum development, writing—second draft preparation and editing; Sandra Saperstein: writing—reviewing and editing; Elizabeth M. Aparicio: methodology; Amy Lewin: methodology and writing—reviewing; Kerry M. Green: methodology, writing—reviewing and editing. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Maryland. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Muñoz Bohorquez, J., Parra, D.C., Saperstein, S.L. et al. Feasibility of Implementing a Mindfulness-Based Online Program for Latina Immigrants and the Staff that Work with Them. Mindfulness 14, 1148–1161 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02123-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02123-6