Abstract

Objectives

Medical students display a high prevalence of psychopathological symptomatology, stress and burnout, which may continue in their time as resident and fully qualified doctors. The aim of this study is to evaluate and compare the effects of a mindfulness-based programme on these variables in an experimental group of medical students who underwent the intervention programme compared to a control group who did not.

Methods

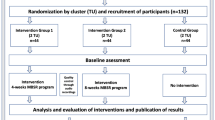

A quasi-experimental study of two independent groups (experimental and control) with two repeated measures (pre and post) was performed. Eight sessions of 2-h duration each were held over the course of 16 weeks. A total of 143 students participated in the study, 68 in the intervention group and 75 in the control group. A sociodemographic questionnaire was administered along with the Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS).

Results

Our study revealed a clear improvement compared to the control group in perceived stress and psychopathological symptomatology, in the Global Severity Index, Positive Symptom Total and the primary symptom dimensions of somatization, obsessive compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity and anxiety of the SCL-90-R. The improvement was significant at both intra- and intergroup level. No impact was found on the level of burnout.

Conclusions

The mindfulness-based programme that was used resulted in an improvement in psychopathological symptomatology and stress, with no effect observed on BO score. This study can contribute to the design of a training programme to promote effective self-care and stress management strategies for both medical students and doctors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Several studies (Dyrbye et al. 2006; Erogul et al. 2014) have shown that medical students display a high prevalence of psychopathological symptomatology (Oró et al. 2019), stress (Salamero et al. 2012; Sender Romeo and Salamero Baró 2007) and burnout, in relation to the general population of their age, a prevalence which continues throughout their training period as resident doctors and subsequently during their professional career as fully qualified doctors (Dyrbye et al. 2014; Voltmer et al. 2008).

Different factors have been described as having relevance in the high levels of psychopathological symptomatology in medical students. These include the high academic requirements for acceptance on a medical degree course, the demanding nature of the contents of the course, the strain of the exams, the pressure of time constraints and the heavy workload (Kaufman et al. 1998; Thomas et al. 2007). These high demands can imply certain types of behaviour and relationship patterns including a predisposition to inadequate social relationships, the reinforcement of patterns of self-demandingness and self-criticism and the manifestation of obsessive or other harmful behavioural patterns (Sender Romeo and Salamero Baró 2007).

In addition, medical students and health professionals in general are subjected to a particular type of stress associated with caring for others, in an overloaded and demanding system. When chronically sustained, this type of stress can give rise to what is known as burnout syndrome or occupational burnout, which is associated with healthcare professions and human service professions in general (Maslach 1982; Shapiro et al. 2005).

In medical students, various studies have found a ˃ 50% prevalence for academic burnout (Cecil et al. 2014; Ishak et al. 2013). Galán et al. (2011) reported that the prevalence of burnout increases as the studies progress, with a score at the end of the degree almost twice as high as at the mid-way point.

High levels of stress and burnout have been associated with depressive symptomatology, suicide risk, alcoholism and substance abuse (Jackson et al. 2016; Shanafelt et al. 2002), as well as with greater interpersonal conflict and diminished clinical performance (Dyrbye et al. 2005; Yuguero et al. 2017). This deterioration in mental health may be sustained in resident doctors (Shanafelt et al. 2002), maintaining an increased risk of depression and the consumption of toxic substances and a lower level of professional satisfaction (Murray et al. 2001).

Numerous programmes have been developed to improve the mental health condition of medical students, both to reduce the levels of anxiety, depression, stress (Shapiro et al. 2000; Slavin and Chibnall 2016) and suicidal ideation (Witt et al. 2019) and to improve wellbeing and medical skills (communication, empathy, compatibility) (Dyrbye et al. 2019; Scheepers et al. 2020). One of the most notable approaches involves the use of mindfulness-based programmes. Mindfulness is a practice which combines both formal and informal structured interventions centred on paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgementally. Mindfulness consists of two components: self-regulation of attention and the way in which one faces experiences. The self-regulation of attention includes a non-judgemental observation and awareness of sensations and thoughts.

In a pioneering trail, Shapiro et al. (1998) used the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programme of Kabat-Zinn (1994) with a sample group of medical students. Their levels of anxiety and other mood disorders were observed to decrease at the same time as their levels of empathy increased. Various initiatives were subsequently developed with mindfulness-based programmes, with improvements found principally in decreased levels of anxiety, stress and burnout and enhanced wellbeing (Rosenzweig et al. 2003; Warnecke et al. 2011). These stress-reducing and wellbeing enhancement effects have also been observed in healthcare professionals (Irving et al. 2009; Krasner et al. 2009), and the improvement appears to be sustained over time (De Vibe et al. 2018). However, some randomized studies found no improvement (Kuhlmann et al. 2016), and various recent reviews have reported contradictory results (Daya and Hearn 2018; McConville et al. 2017), with a clear improvement in stress, but a less clear improvement in burnout or other symptomatology.

Very few studies have been published on the relationship between mindfulness and improvements in psychopathological symptomatology. Jain et al. (2007) described an improvement in medical students in terms of stress level, rumination and distraction. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effects of a mindfulness-based programme on levels of psychopathological symptomatology, stress and burnout in a group of medical students when compared to a control group.

Methods

Participants

The intervention group was comprised of 68 students who were taking the elective course of psychobiology and the control group of 75 students. The control group students were taking other elective courses at the Faculty of Medicine at the same time; these courses were not related to the items assessed in the experimental group. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. Authorization of the centre was obtained and its ethical requirements complied with. All participants signed a written informed consent form.

A total of 143 students participated in the study, 68 in the experimental group and 75 in the control group. Mean age was 20.28 (SD 1.54) years old; 73.4% of participants were female. The participants were distributed between second and fifth year students, with a mean of 2.36 (SD 0.71). No significant differences were found in relation to gender, academic year or age between the control group and the experimental group. A 20.3% of the students claimed to have prior knowledge of mindfulness, meditation, yoga or similar activities, with no significant differences between experimental group and control group.

Procedure

A total of 8 sessions of 2-h duration each were held over the course of 16 weeks. A CD was also given to the participants with recorded exercises to facilitate their practice outside the workshop sessions. The sessions were led by a psychologist trained in mindfulness.

The workshop was structured following the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programme of Kabat-Zinn (Kabat-Zinn 1994, 2005) and included elements of the mindfulness-based cognitive therapy programme of Segal, Williams and Teasdale (Segal et al. 2002) and its adaptation for a non-clinical population by Williams and Penman (2013). Also included small additions of others third wave behavioural and cognitive therapies (Hayes 2004) adapted to peculiarities of medical students. The entire workshop is dotted with contributions from the fields of philosophy, psychology and neurosciences related to mindfulness. Table 1 shows the content of the workshop sessions.

Measures

Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), Spanish adaptation (Derogatis 2002): the SCL-90-R is a 90-item self-report symptom inventory developed by Leonard Derogatis to measure psychological symptoms and psychological distress. It is designed to be appropriate for use with individuals from the community, as well as individuals with either medical or psychiatric conditions. The SCL-90-R assesses psychological distress in terms of nine primary symptom dimensions and three summary scores termed global scores. The principal symptom dimensions are labelled somatization, obsessive compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and psychoticism. The global measures are referred to as the Global Severity Index (GSI), the Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI) and the Positive Symptom Total (PST). Reliability of the subscales and global scales in our study was satisfactory (Cronbach’s alpha (0.72–0.87), excluding additional items scale, composed of miscellaneous items).

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al. 1983) is used to measure the degree to which situations in life are evaluated as stressful. It assesses how unpredictable, uncontrollable and overstrained the lives of the surveyed participants are. The Spanish adaptation of González and Landero (2007) was used, with 14 items evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 to 4) to assess the level of perceived stress during the previous month. A cut-off point is established in the new scale of the test carried out in 2009 by Cohen and Janicki-Deverts (2012), taking as a reference the sample corresponding to the age of the participants in our study.

Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS) (Schaufeli et al. 2002): this is an academic burnout questionnaire adapted for students and derived from the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). It measures 3 factors: emotional exhaustion, cynicism and academic efficacy (the opposite of inefficacy which implies burnout). The academic inefficacy factor (inverse score of academic efficacy) was calculated to facilitate the reading of the results (throughout the study a lowering of the score corresponds to an improvement) and because a total score was also calculated by adding together the scores for emotional exhaustion, cynicism and academic efficacy. A total of 15 items were evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale (from 0 to 6), and in order to pay attention to the cases with a higher level of burnout, the cut-off point was the total score obtained (also with the MBI-SS) in the study by Galán et al. (2011) with medical students from the Faculty of Medicine of Seville.

Data Analyses

The descriptive statistics, level of attendance and level of practice at home were calculated. To calculate intergroup, in addition to intra-group, differences, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed in two factors: test time (pre and post) × group (experimental and control) with repeated measures in only one factor (time). An ANOVA was also performed, within the experimental group, of two factors, test time (pre and post) × level of practice at home (high-medium and low-zero) with repeated measures in only one factor (time), to observe differences as a function of practice at home in the variables in which significant changes were observed. All analyses were performed bilaterally (two-tail) and statistical significance was considered at p ˂ 0.05. The SPSS software programme was used.

Results

There were no significant differences between the experimental and control group in the pre-intervention values, except in the academic efficacy factor of the MBI-SS which was higher in the experimental group (p < 0.005). This factor was also the only one which failed Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance.

In the experimental group, mean attendance was 7.10 sessions (SD 0.88) and average number of hours in the workshop was 13.45 (SD 2.47). High level of practice at home was 4.4% (more than 3 times a week), medium was 29.4% (2–3 times a week or more), low was 48.5% (once a week or occasionally) and 17.6% did zero practice at home.

Table 2 shows the experimental group and control group pre- and post-intervention results of the Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS). As the contrast of mean analysis also found significant pre- and post-intervention differences in the control group, the ANOVA results are shown in order to only take into account the significant changes within the experimental group and with respect to the changes in the control group.

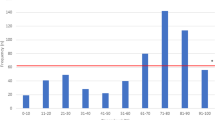

Figure 1 shows the experimental group and control group pre- and post-intervention comparison for the PSS variable, including the scale reference score. Significant differences of improvement were observed in experimental group at both intra- and intergroup level (p < 0.0001) but not the control group. The pre-intervention perceived stress level of the experimental group was higher than that of the control group, though this difference was not significant. The ANOVA showed significant differences in the time × group factor (p = 0.005).

Figure 2 shows the results of the different primary dimensions of the SCL-90-R, as well as the reference score for the general population. Significant differences, at both intra- and intergroup level, were observed in somatization, obsessive compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity and anxiety. No significant differences were found, at either intra- or intergroup level, in depression, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism or additional items.

Figure 3 shows the control group and experimental group pre- and post-intervention comparison for the SCL-90-R variable in the Global Severity Index (GSI), the Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI) and the Positive Symptom Total (PST), with test reference scores in the psychosomatic and general population. The pre-intervention GSI (generalized measure of the intensity of global psychic and psychosomatic suffering) and PST (measure of the extent and diversity of the pathology) scores are at the level of psychosomatic patients. The post-intervention t improvement in the experimental group was significant compared to the control group, and significant differences at both intra- and intergroup scale were found in the GSI and PST. No significant differences were found in the PSDI.

Comparison between the experimental group and the control group of mean pre- and post-intervention scores in the Global Severity Index (GSI), the Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI) and the Positive Symptom Total (PST) of the SCL-90-R, with test scale references in the psychosomatic and general population

Table 3 shows the results of the experimental group for the variables in which significant changes were found when the results were broken down between those with high-medium and those with low-zero level of practice at home. No significant differences were observed. The changes that took place were independent of the level of practice.

Reliability of the scales was satisfactory: the SCL-90-R subscales and global scales Cronbach’s alpha were 0.72–0.87, and the PSS Cronbach’s alpha value for our sample was 0.82. The Cronbach’s alpha for the MBI-SS subscales was 0.77–0.81.

Discussion

All participants (except 3) attended a minimum of 6 sessions. It can therefore be affirmed that the workshop sessions, which were adapted to the characteristics of the participants, were successful in this respect. The high rate of participation (95.5%) is in line with that reported by Phang et al. (2015) in their study.

The level of practice at home is low; it may be related to the fact that, although in these workshop sessions the convenience of practicing the exercise at home was indicated and materials and guidelines for doing so were provided, no personal feedbacks were given on the actual practice carried out by each particular participant. Practicing at home was a recommendation not an obligation and it was felt that the students would appreciate the lack of pressure to practice at home, and consideration was also given to the fact that the motivations of the participants were different to those of an actual group of patients with a specific symptomatology. The results of our research suggest that benefits can be obtained, at least in the short term, with less demands on daily practice time and shorter sessions. Continued practice beyond the normal 8 weeks of the programme may be necessary to consolidate the improvements that were observed, in line with the arguments put forward by Soler et al. (2014).

In our study, a clear improvement in the experimental group was observed with respect to its baseline measure compared with the control group, in the PSS and in psychopathological symptomatology; in both the GSI and PST of the SCL-90-R; and in the primary symptom dimensions of somatization, obsessive compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity and anxiety. No evidence was found of a clear improvement in burnout level.

The pre-intervention scores are high but similar to those in the studies of Erogul et al. (2014), Cohen et al. (1983) and Reed et al. (2011), undertaken with medical students and improve in both the male and female participants in the experimental group (Daya and Hearn 2018).

With respect to the psychopathological symptomatology, the high pre-intervention scores compared to the general population should be noted. The scores are similar to those of the psychosomatic population and only below those of a psychiatric population (Derogatis 2002). These results concur with studies which have detected a risk of psychopathological problems and psychological distress in medical students (Dyrbye et al. 2006; Salamero et al. 2012).

The pre-intervention PSDI (measure which relates the global suffering or ‘distress’ with the number of symptoms and is an indicator of mean symptomatic intensity) is at the level of the general population, making statistically significant changes difficult to obtain. This was indeed the case as, despite the greater improvement seen in the experimental group, significant changes with respect to the control group were not observed.

With respect to the SCL-90-R, the experimental group shows a significant improvement, with the post-intervention scores approaching the mean of the general population. The pre-intervention scores were closer to the reference scores of the psychosomatic population than the general population, in concurrence with studies which have detected a risk of psychopathological problems and psychological distress in medical students (1–6). The pre-intervention obsessive compulsive scores were at the level of the psychiatric population but fell below post-intervention. This is in line with results of Jain et al. (2007), who observed a reduction in rumination. The changes were significant in four of the nine dimensions (somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity and anxiety) and non-significant in the remaining dimensions.

In order to acquire a perspective with a sample similar to that of our study, the pre- and post-intervention experimental group data were compared with those of the study by Hassed et al. (2009), who used 148 first-year medical students at Monash University (Australia). It was only possible to compare the depression, anxiety and hostility dimensions and the GSI, as these were the only SCL-90-R scores recorded in that study. According to the authors of that study, those three dimensions and the GSI scale were chosen after consultation of the literature on psychological health in medical students and the psychological effects of mindfulness-based interventions. Our pre-intervention experimental group scores were higher (Hassed already considered their scores to be higher than the reference score), underlining the argument that our experimental group displayed considerable symptomatology. The post-intervention scores were better in the study by Hassed but, when taking as the starting point our pre-intervention scores, the effects of the intervention in our study were higher in these comparable variables.

It is difficult to find studies of a similar nature to ours which have used the SCL-90-R, with most of them using the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), which is a shortened version of the SCL-90-R.

In contrast, no clear changes in the burnout scores were observed in our study, as is the case with previous studies (Daya and Hearn 2018). There are contradictory reports in the literature about the effectiveness of mindfulness training on burnout. Some studies made with doctors and healthcare professionals have reported a positive effect (Fortney et al. 2013; Martín et al. 2013), whereas another study with medical and psychology students reported no effect on burnout (De Vibe et al. 2018). It may be the case that a study undertaken with medical professionals is not comparable with the use of medical students in our study, or other factors may have been at play.

Our study showed significant reductions in stress and psychopathological symptomatology, and following the transactional stress model of Lazarus and Folkman (1984), mindfulness intervention acts in such a way that the students are better able to modulate the influence of stress and their response to it, increasing acceptance of it and the appropriate ways of dealing with it (Kabat-Zinn 2005). These effects are not only important in terms of mental health improvement but also in terms of clinical performance.

In view of the health problem that was detected and the results obtained, this study can contribute to the design of a training programme for medical students to promote self-care and stress management strategies, which can be effective both while studying medicine and subsequently in their professional careers.

As stressed by Dobkin and Hutchinson (2013), this type of intervention can be offered as a complementary or extracurricular activity, as an elective course or even as a part of the main training curriculum. Given the low impact on improvement in burnout, future interventions are recommendable in combination with other strategies to ensure its prevention or its management.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present study has several limitations worthy of consideration. First, it should be noted that the study was carried out in a specific faculty of medicine, the groups were not randomized and there has been no subsequent follow-up. Another study limitation was that we did not measure the impact of a possible contamination between the groups. As this was conducted at one medical school, the control group maybe have practiced mindfulness, influenced by the intervention group. Likewise, as a limitation in the interpretation of the results, it must be taken into account that the comparison of scores was made with the general standards of each test by age, but no specific time and population standards were available.

Future research should explore barriers to mindfulness use and ways to promote a more equally distributed use of mindfulness-based practices and programs. In addition, the concept of burnout could be examined further. Future research should evaluate the effects that appeared in the control group, controlling possible contamination, as well as whether the effects are reproducible in a greater number of medical schools. Furthermore, the concept of burnout should be examined further, in relation to the factors that may contribute to its appearance.

References

Cecil, J., McHale, C., Hart, J., & Laidlaw, A. (2014). Behaviour and burnout in medical students. Medical Education Online, 19(1), 25209.

Cohen, S., & Janicki-Deverts, D. E. N. I. S. E. (2012). Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(6), 1320–1334.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

Daya, Z., & Hearn, J. H. (2018). Mindfulness interventions in medical education: A systematic review of their impact on medical student stress, depression, fatigue and burnout. Medical Teacher, 40(2), 146–153.

de Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Rosenvinge, J. H., Tyssen, R., Hanley, A., & Garland, E. (2018). Six-year positive effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on mindfulness, coping and well-being in medical and psychology students; results from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One, 13(4), e0196053.

Derogatis, L. R. (2002). SCL-90-R. Cuestionario de 90 síntomas. Manual. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

Dobkin, P. L., & Hutchinson, T. A. (2013). Teaching mindfulness in medical school: Where are we now and where are we going? Medical Education, 47(8), 768–779.

Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2005). Medical student distress: Causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 80(12), 1613–1622.

Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2006). Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among US and Canadian medical students. Academic Medicine, 81(4), 354–373.

Dyrbye, L. N., West, C. P., Satele, D., Boone, S., Tan, L., Sloan, J., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2014). Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Academic Medicine, 89(3), 443–451.

Dyrbye, L. N., Sciolla, A. F., Dekhtyar, M., Rajasekaran, S., Allgood, J. A., Rea, M., et al. (2019). Medical school strategies to address student well-being: A national survey. Academic Medicine, 94(6), 861–868.

Erogul, M., Singer, G., McIntyre, T., & Stefanov, D. G. (2014). Abridged mindfulness intervention to support wellness in first-year medical students. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 26(4), 350–356.

Fortney, L., Luchterhand, C., Zakletskaia, L., Zgierska, A., & Rakel, D. (2013). Abbreviated mindfulness intervention for job satisfaction, quality of life, and compassion in primary care clinicians: A pilot study. The Annals of Family Medicine, 11(5), 412–420.

Galán, F., Sanmartín, A., Polo, J., & Giner, L. (2011). Burnout risk in medical students in Spain using the Maslach burnout inventory-student survey. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 84(4), 453–459.

González, M. T., & Landero, R. (2007) Factor structure of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) in a sample from Mexico. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10(1), 199–206.

Hassed, C., De Lisle, S., Sullivan, G., & Pier, C. (2009). Enhancing the health of medical students: Outcomes of an integrated mindfulness and lifestyle program. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(3), 387–398.

Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 639–665.

Irving, J. A., Dobkin, P. L., & Park, J. (2009). Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: A review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 15(2), 61–66.

IsHak, W., Nikravesh, R., Lederer, S., Perry, R., Ogunyemi, D., & Bernstein, C. (2013). Burnout in medical students: A systematic review. The Clinical Teacher, 10(4), 242–245.

Jackson, E. R., Shanafelt, T. D., Hasan, O., Satele, D. V., & Dyrbye, L. N. (2016). Burnout and alcohol abuse/dependence among US medical students. Academic Medicine, 91(9), 1251–1256.

Jain, S., Shapiro, S. L., Swanick, S., Roesch, S. C., Mills, P. J., Bell, I., & Schwartz, G. E. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(1), 11–21.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. New York: Hyperion.

Kaufman, D. M., Mensink, D., & Day, V. (1998). Stressors in medical school: Relation to curriculum format and year of study. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 10(3), 138–144.

Krasner, M. S., Epstein, R. M., Beckman, H., Suchman, A. L., Chapman, B., Mooney, C. J., & Quill, T. E. (2009). Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. Jama, 302(12), 1284–1293.

Kuhlmann, S. M., Huss, M., Bürger, A., & Hammerle, F. (2016). Coping with stress in medical students: Results of a randomized controlled trial using a mindfulness-based stress prevention training (MediMind) in Germany. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 1–11.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Martín, A., Rodríguez, T., Pujol-Ribera, E., Berenguera, A., & Moix, J. (2013). Evaluación de la efectividad de un programa de mindfulness en profesionales de atención primaria. Gaceta Sanitaria, 27(6), 521–528.

Maslach, C. (1982). Burnout: The cost of caring. Nueva York: Prentice-Hall.

McConville, J., McAleer, R., & Hahne, A. (2017). Mindfulness training for health profession students—The effect of mindfulness training on psychological well-being, learning and clinical performance of health professional students: A systematic review of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. Explore, 13(1), 26–45.

Murray, A., Montgomery, J. E., Chang, H., Rogers, W. H., Inui, T., & Safran, D. G. (2001). Doctor discontent: A comparison of physician satisfaction in different delivery system settings, 1986 and 1997. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(7), 452–459.

Oró, P., Esquerda, M., Viñas, J., Yuguero, O., & Pifarré, J. (2019). Síntomas psicopatológicos, estrés y burnout en estudiantes de medicina. Educacion Medica, 20(1), 42–48.

Phang, C. K., Mukhtar, F., Ibrahim, N., Keng, S. L., & Sidik, S. M. (2015). Effects of a brief mindfulness-based intervention program for stress management among medical students: The mindful-gym randomized controlled study. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 20(5), 1115–1134.

Reed, D. A., Shanafelt, T. D., Satele, D. W., Power, D. V., Eacker, A., Harper, W., et al. (2011). Relationship of pass/fail grading and curriculum structure with well-being among preclinical medical students: A multi-institutional study. Academic Medicine, 86(11), 1367–1373.

Rosenzweig, S., Reibel, D. K., Greeson, J. M., Brainard, G. C., & Hojat, M. (2003). Mindfulness-based stress reduction lowers psychological distress in medical students. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 15(2), 88–92.

Salamero, M., Baranda, L., Mitjans, A., Baillés, E., Càmara, M., Parramon, G., & Padrós, J. (2012). Estudi sobre la salut, estils de vida i condicionants acadèmics dels estudiants de medicina de Catalunya. Barcelona: Fundació Galatea.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92.

Scheepers, R. A., Emke, H., Epstein, R. M., & Lombarts, K. M. (2020). The impact of mindfulness-based interventions on doctors’ well-being and performance: A systematic review. Medical Education, 54(2), 138–149.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford Press.

Sender Romeo, R., & Salamero Baró, M. (2007). Programa de atención psicológica para los alumnos de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Barcelona. Educación Médica, 10(4), 58–63.

Shanafelt, T. D., Bradley, K. A., Wipf, J. E., & Back, A. L. (2002). Do medical residents experience burnout? Annals of Internal Medicine, 136(5), 29.

Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G. E., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(6), 581–599.

Shapiro, S. L., Shapiro, D. E., & Schwartz, G. E. (2000). Stress Management in Medical Education:A review of the literature. Academic Medicine, 75(7), 748–759.

Shapiro, S. L., Astin, J. A., Bishop, S. R., & Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management, 12(2), 164.

Slavin, S. J., & Chibnall, J. T. (2016). Finding the why, changing the how: Improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Academic Medicine, 91(9), 1194–1196.

Soler, J., Cebolla, A., Feliu-Soler, A., Demarzo, M. M., Pascual, J. C., Baños, R., & García-Campayo, J. (2014). Relationship between meditative practice and self-reported mindfulness: The MINDSENS composite index. PLoS One, 9(1), e86622.

Thomas, M. R., Dyrbye, L. N., Huntington, J. L., Lawson, K. L., Novotny, P. J., Sloan, J. A., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2007). How do distress and well-being relate to medical student empathy? A multicenter study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(2), 177–183.

Voltmer, E., Kieschke, U., Schwappach, D. L., Wirsching, M., & Spahn, C. (2008). Psychosocial health risk factors and resources of medical students and physicians: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 8(1), 46.

Warnecke, E., Quinn, S., Ogden, K., Towle, N., & Nelson, M. R. (2011). A randomised controlled trial of the effects of mindfulness practice on medical student stress levels. Medical Education, 45(4), 381–388.

Williams, J. M. G., & Penman, D. (2013). Mindfulness: guía práctica: para encontrar la paz en un mundo frenético. Barcelona: Paidós.

Witt, K., Boland, A., Lamblin, M., McGorry, P. D., Veness, B., Cipriani, A., et al. (2019). Effectiveness of universal programmes for the prevention of suicidal ideation, behaviour and mental ill health in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 22(2), 84–90.

Yuguero, O., Marsal, J. R., Buti, M., Esquerda, M., & Soler-González, J. (2017). Descriptive study of association between quality of care and empathy and burnout in primary care. BMC Medical Ethics, 18(1), 54.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PO designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses and wrote the paper. ME collaborated with the design and writing of the study, BM analysed the data and collaborated in the editing of the final manuscript, JV collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript, OY analysed the data and wrote part of the results, and JP analysed the data and collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of APA and the institutional and national research committee, as well as following the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, its later amendments and comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was provided by the University of Lleida.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oró, P., Esquerda, M., Mas, B. et al. Effectiveness of a Mindfulness-Based Programme on Perceived Stress, Psychopathological Symptomatology and Burnout in Medical Students. Mindfulness 12, 1138–1147 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01582-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01582-5