Abstract

Initial detrital composition and authigenic alterations during diagenesis of three sandstone types are related to their mechanical properties. Sandstones were prepared for geotechnical standard tests [density, uniaxial compressive strength (UCS), Young’s modulus (E), strain at failure (ε)] and thin sections for petrographic analyses (point counting). UCS ranges from 3 to 62 MPa and positively correlates with density (1.75–2.35 g/cm3) and E (0.3–12.7 GPa). Optical porosity is controlling these mechanical parameters and was linked to diagenetic alterations. Diagenetic alterations affecting porosity reduction are the abundance of clay minerals, and the intensity of mechanical and chemical compaction. The latter is controlled by clay mineral coatings on contacts between detrital grains, and the occurrence of authigenic quartz and dolomite. Horizontal contact lengths of grains normalized to their respective particle diameter (effective contact ratio, ECR) and porosity are identified as a control on the mechanical properties UCS and E, reflected by the rock strength index SR. The results of this pilot study suggest that SR is able to predict UCS and E based on petrographic information obtained from the studied samples. These results enhance the understanding of the coupling between mineralogy and geomechanics and highlight the impact of diagenesis on geomechanical behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deeply buried Lower Permian Rotliegend sandstones are the most important reservoir rocks for natural gas in Central Europe (Gast et al. 2010). These reservoirs are of increasing interest for applications other than hydrocarbon extraction, such as geothermal energy exploration, gas and hydrogen storage, or CO2 sequestration (Ambrose et al. 2008; Bachu 2000; Legarth et al. 2005; Moeck et al. 2009; Regenspurg et al. 2015). The pore pressure and effective stress of these porous reservoir rocks will decrease during production in hydrocarbon or geothermal reservoirs, which may result in compaction and / or rock failure over reservoir timescales [e.g. Hettema et al. (2000); Talwani and Acree (1985); Zoback and Zinke (2002)]. Therefore, studies assessing geomechanical properties are well-established methods in reservoir studies (Ghassemi 2012; Sayers and Schutjens 2007). Reservoir sandstones also compact mechanically and chemically over geological timescales affecting petrophysical and mechanical properties (Houseknecht 1987; Lundegard 1992). Their reservoir properties change during subsidence, and their diagenesis is related to initial composition and grain coatings (Aagaard et al. 2000; Busch et al. 2020; Monsees et al. 2020), fluid type, chemistry and pressure (Bjørlykke and Høeg 1997; Gaupp et al. 1993), thermal exposure over time at depth intervals (Becker et al. 2019; Busch et al. 2018; Lander et al. 2008), and faults controlling temperature overprint by hydrothermal fluid circulation (Wüstefeld et al. 2017). It is thus of crucial importance for assessing the rock’s porosity and permeability, and its viability as a reservoir (Morad et al. 2010; Worden et al. 2018).

Empirical relations between parameters like rock strength and deformability are well established (Chang et al. 2006; Dyke and Dobereiner 1991) and have been correlated with the bulk sandstone composition (Fahy and Guccione 1979; Ulusay et al. 1994; Zorlu et al. 2008). Fahy and Guccione (1979) demonstrated the dependence of compressive rock strength on grain sizes, quartz percentage, sphericity, cements and grain contacts. Dyke and Dobereiner (1991) showed that the length of the grain contacts in relation to the total grain surface length can be used as a proxy for compressive strength in sandstones. Zorlu et al. (2008) performed multiple regression analysis on a large sandstone data set (n = 138), evaluating and quantifying the effects of quartz content, cement volumes, grain size, grain contacts and packing density on compressive strength. They concluded that packing density, grain contacts and quartz content are the most important parameters.

The objective of this study is to investigate and quantify relationships between diagenetic and geomechanical properties of porous sandstones. In this context, petrographic data is gathered from optical microscopy, point-counting, grain-coating analyses, and effective contact ratios (ECR). The petrographic data will be compared with geomechanical data, using uniaxial compression tests, delivering data on Young’s modulus (E), uniaxial compressive strength (UCS), density and strain at failure (ε). The influence of petrographic parameters and diagenesis on geotechnical parameters will be evaluated and quantified and discussed with respect to reservoir- and geological timescales.

Geological setting

The sandstones of the Cornberg quarry (CS) belong to the uppermost Rotliegend (Lower Permian) lithostratigraphic unit (Kowalczyk et al. 2012), also referred to as the Weißliegend (Paul 2012). The Cornberg Formation crops out in the Nentershäuser Basin, which is a sub basin of the Hesse Basin in central Germany (Kulick et al. 1984) (Fig. 1a). The Nentershäuser Basin has been interpreted as a pull-apart basin due to its thickness increase of Rotliegend deposits from tens to hundreds of meters over lateral distances < 10 km (Kowalczyk et al. 2012; Kulick et al. 1984). Based on meter-scale cross-bedded strata, the depositional system of the sandstones has been controversially discussed (Gast 1994; Pryor 1971; Schumacher 1985). Recent studies interpret them to be of eolian origin (Gast 1994; Kowalczyk et al. 2012). The thickness of the formation is up to 20 m (Kowalczyk et al. 2012), being conformably overlain by the Kupferschiefer claystone marking the onset of the Zechstein transgression (Kowalczyk et al. 2012), and underlain by grey, sandy conglomerates and red conglomeratic sandstones and pelites (Aehnelt and Katzung 2007). Maximum burial depth and precise inversion timing is unclear (Kowalczyk et al. 2012).

modified from Fischer et al. (2012). d Overview map of western Central Europe, showing the study areas in Germany and the UK

Schematic geological maps of the vicinity of the studied quarries. a Extent of Rotliegend deposits in the northern Hesse Basin, redrawn from Kowalczyk et al. (2012). b Present-day geology of the Vale of Eden highlighting the extent of Rotliegend deposits, redrawn from Turner et al. (1995). c Geology of the Flechtingen High, showing the location of fluvio-eolian Rotliegend marginal deposits,

Upper Rotliegend fluvio-eolian Flechtingen Sandstones (FS) are exposed in a decommissioned quarry 1 km southwest of Bebertal, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany (Fig. 1b), located on the margins of the Flechtingen High (Gaitzsch et al. 2004). Rocks of the Bebertal quarry are commonly used as analogs for the North German Rotliegend hosted reservoirs (Fischer et al. 2012; Gast et al. 2010; Schröder et al. 1995). According to the regional stratigraphic correlation conducted by Schneider and Gebhardt (1993) and field studies by Gaitzsch et al. (2004), the Rotliegend sandstones exposed near Bebertal belong to the Mirow Formation of the Havel Subgroup, resulting in a sedimentation age between 264 and 262 Ma (Menning 1995). The series has a thickness of 10–16 m (Gaitzsch et al. 2004) and is conformably underlain by conglomerates (the Oberes Konglomerat series), and unconformably overlain by dominantly fluvial sandstones (the Oberer Rundkörniger Sandstein series) (Gaitzsch et al. 2004). Flechtingen Sandstones were rapidly buried reaching a thermal maximum of 200–250 °C in early Triassic (Fischer et al. 2012), and subsequently uplifted by the inversion of the Flechtingen High initiated during the Late Aptian transgression (Otto 2003).

Permian Penrith Sandstones (PS) crop out in the Vale of Eden half graben, Cumbria, UK (Fig. 1c), covering an area of approximately 48 × 6 km (Busch et al. 2017; Macchi 1981; Turner et al. 1995). The Appleby Group consists of the eolian Penrith Formation and basal alluvial deposits locally referred to as the Brockram facies (Macchi 1981), and is time—equivalent to the Central European Rotliegend (Jackson et al. 1997). The total thickness of the Penrith Sandstone is discussed to reach up to 1 km (Turner et al. 1995). Upper Carboniferous siliciclastic rocks in the northern Vale of Eden and Lower Carboniferous limestones in the south are unconformably overlain by the Appleby Group (Arthurton and Wadge 1981; Macchi 1981; Turner et al. 1995). The Appleby Group is conformably overlain by shales, evaporites and dolomite of the Zechstein, which are combined in the Eden Shales Formation (Arthurton and Wadge 1981). The Penrith Sandstones were buried to maximum burial depth up to 3500 m (120 °C) in the Cretaceous, and were inverted in the Late Cretaceous/Early Tertiary (Turner et al. 1995).

Materials and methods

Large rock samples were taken from quarries and drilled normal to bedding for geomechanical analyses, and parallel to bedding for petrographic analysis. A total of seven polished thin sections originating from each of the seven rock samples used to prepare the cylinders [CS (n = 2), FS (n = 2) and PS (n = 3)] were analyzed. The thin sections were impregnated with a blue-dyed epoxy resin to highlight porosity. Thin sections are prepared to a thickness of 30 µm and stained with a combined Alizarin Red S and potassium ferricyanate solution to aid the identification of carbonate minerals. Sample PS1 and PS2 originate from quarry A, while sample PS3 originates from quarry B (Fig. 1b).

Grain sizes were measured along their long axis on 100 grains with digital image analysis using ImageJ (Becker et al. 2017). Median grain sizes determined by digital image analysis have been demonstrated to reach accuracies of > 96% compared to conventional methods like sieving (Barnard et al. 2007). Sorting was determined according to Trask (1930). Point counting (300 counts) was performed on a grid adjusted to the maximum grain size with a semi-automated Pelcon Point Counter installed on a Leitz Aristomet microscope. This leads to a point-counted area of 350–500 mm2 considering step size and grain size. Point-counted optical porosity was used as a benchmark for the representative elementary area (volume) of the thin sections, compared to increasing areal dimensions covered on comparator images. Consistent porosities were obtained from comparator images of Cornberg Sandstones with an area larger 100 mm2, from Flechtingen Sandstones for an area larger than 150 mm2, and for Penrith Sandstones for an area larger than 30 mm2. The minimum point-counted area controlled by grain size and step size is larger than 300 mm2; therefore, delivering porosities in agreement with the representative elementary volume concept. The statistical error of the arithmetic mean of point-counting data was determined by dividing the standard deviation by the square root of the number of samples.

The sandstone compositions were classified after Folk (1980). The intergranular volume (IGV) was classified according to Paxton et al. (2002). The IGV is the sum of the intergranular pore space, the intergranular cement and detrital matrix. Compactional porosity loss versus cementational porosity loss and compactional indices were calculated after Lundegard (1992), and used to determine the compactional index (Lundegard 1992). The compactional index is the fractional ratio of compaction porosity loss and the sum of compaction porosity loss plus the cementation porosity loss, assuming an initial porosity of 45%. The value ranges between zero (porosity loss only by cementation) and one (porosity loss only by compaction). The percentage of clay mineral coatings on grain-to-IGV (GTI) interfaces was assessed on at least 50 grains per sample (Busch et al. 2020). Both the part of a grain’s circumference in contact with the IGV and the length of the GTI interface covered with clay minerals were manually measured using image analysis software. The grain’s aspect ratio was normalized as a percentage, and averaged over at least 50 measurements per sample. Percentages of illite coatings on grain-to-grain (GTG) detrital quartz interfaces were evaluated after Monsees et al. (2020) by microscopy-aided image analysis. GTG coatings determine the clay coat coverage on grain–grain contacts in contrast to the total length of the grain’s circumference in contact with other grains.

The effective contact length (ECL) is introduced as a new approach to quantify the length of physical quartz–quartz, quartz–feldspar and feldspar–feldspar particle contacts (grain plus syntaxial cement) orientated subparallel (max. ± 20°) to the bedding axis (Fig. 2a). Possible syntaxial cementation of grains is included in the contact length (Fig. 2a). It quantifies what otherwise is noted as point, long, convex–concave and sutured contact (Schmidt et al. 2020; Taylor 1950) but here also includes contacts of syntaxial overgrowth cements on detrital grains. The effective contact length was determined by digital image analysis with ImageJ on randomly selected grain contacts using oriented thin sections. A total of at least n = 50 grain contacts are measured per sample. Median grain size is used as a quality check for the representability of the sample’s population (Fig. 2b). The effective contact length was normalized by the grain diameter of the smaller of the two touching grains (Dg), measured by image analysis along its long axis and resulting in the effective contact ratio (ECR). An averaged diameter of both touching grains is avoided since the diameter of the smaller grain limits the effective contact length (ECL). The effective contact ratio is a grain-size independent parameter quantifying the relative contact area of strong mineral contacts in porous siliciclastic rocks. A rock strength index SR was determined by dividing the optical porosity (ϕ) with the effective contact ratio (ECR).

a Effective contact lengths were determined on physical contacts between detrital grains with and without syntaxial cements. Only contacts within ± 20° to the true horizontal were measured. Stress direction is normal to the horizontal. b Median grain size used as quality control on average effective contact length

The uniaxial compression test according to DIN18136 (2003) and Mutschler (2004) determines the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) as well as Young’s modulus (E). The cylindrical specimens are cored from rock samples normal to bedding with a diameter of 38.1–92.5 mm, the height of the specimens ranges from 68.6 to 203.6 mm. For the study, 19 cylinders were drilled out of seven rock samples: Cornberg Sandstone (n = 5), Flechtingen Sandstone (n = 2) and Penrith Sandstone (n = 12). The test results and sample dimensions are shown in Table 1.

The cylinders are loaded in axial direction at a constant deformation rate with unconstrained lateral expansion. The test speed is approx. 0.5–1% of the initial height of the specimen per minute. The test is considered to be completed when the specimen has fractured (i.e. the measured axial force does not increase any further) or the strain has reached a value of 20%. For the evaluation, the uniaxial compressive strength UCS, the associated strain during fracturing εv and the Young’s modulus E is determined from the stress–strain-diagram. Results of geotechnical tests are displayed as averages with their measured ranges.

Results

Rock composition

Detrital components

Texture

Measured grain sizes range from 0.275 to 0.488 mm (Table 3). Cornberg Sandstones show a uniform, homogenous texture with barely visible bedding (Fig. 3) and are very well sorted (Table 3). Flechtingen Sandstones show distinct bedding, as well as bedding-bound heterogeneities (Fig. 3b) and are very well sorted (Table 3). Penrith Sandstones generally are very homogenous (Fig. 3c) with very well to extremely well sorting (Table 3).

Results of petrographic analyses. a Overview photomicrograph of Cornberg Sandstone (sample CS 1, ppl) containing quartz as the dominant detrital mineral. Authigenic TiOx occurs in open pores. b Overview photomicrograph of Flechtingen Sandstone (sample FS 2, ppl), containing K-feldspar and VRF besides quartz grains and open porosity. c Overview photomicrograph of Penrith Sandstone (sample PS 1, ppl), containing detrital quartz encompassed by pore-lining FeOx, overgrown by authigenic quartz. d Photomicrograph of CS (sample CS 2, xpl). Pore-filling illite, dolomite rhombs, pore-filling FeOx. e Photomicrograph of FS (sample FS 1, xpl). Tangential pore-lining illite grain coatings encompassing quartz grains, as well as grain-to-grain illite coatings (GTG coating). f Photomicrograph of PS (sample PS 3, xpl). Tangential pore-lining illite grain coatings, as well as pigmented FeOx rims. FeOx rims were observed to be overgrown by authigenic quartz, while continuous illite coatings were observed to inhibit quartz overgrowth. h Ternary sandstone diagram after Folk (1980), showing sandstone types for the different study areas. Cornberg Sandstones were classified as subarkoses, FS were classified as lithic arkoses to feldsphatic litharenites, and PS were categorized as sublitharenites to quartzarenites. i Porosity-loss diagram after Lundegard (1992). FS samples are mostly compaction dominated, while CS and PS plot in the slightly compaction to slightly cementation dominated area, with PS being able to retain significantly more open porosity. Por open porosity, Qtz quartz, TiOx titanium oxide, ppl plane polarized light, xpl cross-polarized light, Kfs K-feldspar, VRF volcanic rock fragment, FeOx iron oxides, cmt cement, Ill illite, pl pore-lining, pf pore-filling, dol dolomite, GTG grain-to-grain, GTI grain-to-intergranular-volume

Composition

Quartz (incl. metaquartzite, Fig. 3a–f) consistently is the most abundant detrital constituent in all studied samples (CS avg.: 64.0 ± 1.7%, FS avg.: 48.5 ± 1.1%, PS avg.: 61.9 ± 3.1%,) (Table 2). All samples contain minor amounts of feldspars (avg. PS: 3.1 ± 0.4%) and rock fragments (avg. CS: 2.8 ± 0.1%, avg. FS: 14.3 ± 3.7%), which are the second to third most abundant detrital constituents, depending on sample location (Fig. 3b; Table 2). Rock fragments in samples from FS are mainly volcanic rock fragments (VRF: 10.0 ± 3.1%, plutonic RF: 2.2 ± 0.5%, sedimentary RF: 1.0 ± 0.0%, metamorphic RF: 0.8 ± 0.1%, undifferentiated RF: 0.3 ± 0.0%). Rock fragments in PS are mainly volcanic and undifferentiated (VRF: 0.7 ± 0.1%, undifferentiated RF: 0.4 ± 0.2%, sedimentary RF: 0.4 ± 0.2%, plutonic RF: 0.1 ± 0.1%). The most common rock fragments in Cornberg Sandstones are undifferentiated rock fragments (undifferentiated RF: 1.5 ± 0.3%, sedimentary RF: 1.0 ± 0.1%, metamorphic RF: 0.3 ± 0.2%). Detrital clay mineral matrix and mica are very rare (avg. < 1.0%) throughout all studied locations (CS avg.: 0.0 ± 0.1%, FS avg.: 0.8 ± 0.3%, PS avg.: 0.3 ± 0.2%), while zircon appears only in traces (avg. < 0.3%) (Table 2). The studied rock samples show a distinct clustering in sandstone types after Folk (1980). Cornberg Sandstones are sublitharenites to quartzarenites, Flechtingen Sandstones lithic arkoses to feldspathic arkoses, while Penrith Sandstones are classified as subarkoses (Fig. 3h).

Authigenic minerals

Composition

The most abundant authigenic minerals are quartz and illite. Quartz cement ranges between 6.0 and 14.3% (CS avg.: 7.2 ± 0.7%, FS avg.: 5.7 ± 0.4%, PS avg.: 13.1 ± 0.5%) (Fig. 3c; Table 2). Pore-filling illite ranges between 0.3 and 9.0% (CS avg.: 8.8 ± 0.1%, FS avg.: 1.2 ± 0.5%, PS avg.: 0.3 ± 0.2%, Fig. 3d), while pore-lining illite ranges from 0.7 to 4.7% (CS avg.: 1.0 ± 0.2% FS avg.: 4.8 ± 0.1%, PS avg.: 2.2 ± 0.5%) (Fig. 3e, f).

Dolomite cements (avg.: 5.7 ± 1.4%) and pore-filling kaolinite (avg.: 1.3 ± 0.2%) are only present in the Cornberg Sandstones (Fig. 3d). Cornberg Sandstone samples also contain pore-filling FeOx cements (avg.: 1.7 ± 0.6%) (Fig. 3d), authigenic anatase (avg.: 1.2 ± 0.1%) (Fig. 3a), and barite in traces (avg. < 0.3%) (Table 2).

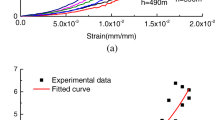

Cross-plots of geotechnical tests, with all tested parameters plotted against each other. Symbols indicate average values of tested samples; bars represent the measured range of values. Linear lines of best fit indicate correlations and the corresponding R2. The outlier sample PS3 in (a) negatively affects an otherwise good correlation. a and b indicate rows sharing the same y-axis, while 1, 2, and 3 indicate colums sharing the same x-axis. UCS Uniaxial compressive strength, E Young’s modulus, ε strain at failure

The Flechtingen Sandstone shows feldspar cements (avg.: 1.2 ± 0.1%), pore-lining FeOx (avg.: 0.8 ± 0.1%) and pore-filling FeOx (avg.: 0.7 ± 0.1%).

Authigenic minerals are less frequent in the Penrith Sandstones. They include authigenic anatase (avg.: 1.1 ± 0.2%), pore-lining FeOx (avg.: 0.8 ± 0.1%) (Fig. 3c, f), pore-filling FeOx (avg.: 0.6 ± 0.3%), and pore-filling illite (avg.: 0.3 ± 0.2%), while feldspar cements occur only in traces (avg. > 0.3%).

Grain coating phases

Grain-to-grain clay coating coverages range from 20 to 21% in Cornberg Sandstones, from 28 to 35% in Flechtingen Sandstones, and from 11 to 18% in Penrith Sandstones (Table 3). Grain-to-IGV clay coatings range from 20 to 34% in Cornberg Sandstones, from 50 to 55% in Flechtingen Sandstones, and from 15 to 22% in Penrith Sandstones (Table 3).

Optical porosity

Intergranular porosities of Cornberg Sandstone samples are on average at 2.7 ± 0.6%, with low intragranular porosities (avg.: 0.3 ± 0.2%), resulting in optical porosities of up to 3.7% (Table 3). Intergranular porosities in Flechtingen Sandstone samples are on average 4.0 ± 0.8%, while intragranular porosity contributes on average 4.0 ± 0.4% to the optical porosity, totaling at an average of 8.0%. Penrith Sandstones show intergranular porosities on average at 18.9 ± 1.5%, intragranular porosity of 1.3 ± 0.2% and total optical porosities of 20.2 ± 1.4%. Sample PS3 is an outlier compared to PS1 and PS3 showing highest measured optical porosities at 23.7%.

Compaction

The Cornberg Sandstones experienced a balanced porosity reduction between compactional and cementational porosity loss (avg. compaction index: 0.51, Fig. 3i) with IGVs ranging from 28.7 to 30.7% (avg.: 29.7%). Porosity in Flechtingen Sandstones was dominantly reduced by compaction (avg. compaction index: 0.75, Fig. 3i), leading to IGVs from 17.0 to 21.3% (avg.: 19.2%). Penrith Sandstones are slightly dominated by porosity loss by cementation (avg. compaction index: 0.43, Fig. 3i). Their IGVs are ranging from 33.3 to 40.7% (avg.: 37.0 ± 1.0%). Sample PS3 records the highest IGV at 40.7% and the lowest compactional index of 0.30 (Table 3).

Effective contact lengths and effective contact ratio

Effective contact lengths range from 0.15 to 0.22 mm for Cornberg Sandstones, from 0.15 to 0.18 mm for Flechtingen Sandstones, and from 0.13 to 0.20 mm for Penrith Sandstones (Table 3). The normalized effective contact ratio ranges from 67.2 to 67.3% for Cornberg Sandstones, from 64.7 to 68.6% for Flechtingen Sandstones, and from 56.4 to 62.2% for Penrith Sandstones (Table 3).

Rock mechanics

Results of geotechnical tests are displayed as averages with their measured ranges (Fig. 4). The unconfined compressive strength (UCS) ranges from 3.2 to 61.7 MPa (Table 1). Cornberg Sandstones show highest average strength (UCS 57.6 MPa), Flechtingen Sandstones shows comparable strength (avg. UCS 53.9 MPa) and Penrith Sandstones show the lowest average compressive strength (avg. UCS 16.4 MPa) (Table 1, Fig. 4). Rock failure was observed at fracture angles between 65 and 85°. Strain at failure ε ranges from 0.46 to 1.05% (Table 1), with strain at failure averages of 0.58% (CS), 0.70% (FS) and 0.64% (PS) for the respective sample locations. Young’s modulus ranges from 0.324 to 12.679 GPa. Cornberg Sandstones show highest Young’s moduli (avg.: 11.597 GPa, range: 9.921–12.679 GPa), followed by Flechtingen Sandstones (avg.: 9.988 GPa, range: 8.997–10.979 GPa), while Penrith Sandstones are lowest (avg.: 4.865 GPa, range: 0.319–7.422 GPa). Bulk densities range from 1.71 to 2.35 g/cm3, with Flechtingen Sandstones showing the highest densities (avg.: 2.31 g/cm3, range: 2.27–2.35 g/cm3), closely followed by Cornberg Sandstones with very similar densities (avg.: 2.28 g/cm3, range: 2.25–2.30 g/cm3). The densities in Penrith Sandstones samples are lower (avg.: 1.99 g/cm3, range: 1.71–2.11 g/cm3) (Table 1).

Correlations of petrographic and mechanical properties

Petrographic correlations

Optical porosity shows a negative correlation with the effective contact ratio (ECR, R2 = 0.91) (Fig. 5f1). The intergranular volume shows a positive correlation with quartz cements (R2 = 0.73) (Fig. 5a2) and a positive correlation with the compactional index (R2 = 0.92) (Fig. 5c2). It seems to be negatively correlated with ECR (R2 = 0.61) (Fig. 5f2), but does not clearly correlate with the median grain size (R2 = 0.47) (Fig. 5d2). Grain-to-grain and grain-to-IGV clay coatings show a negative correlation with quartz cements (R2 = 0.69, R2 = 0.66) (Fig. 5a3, a4) and a negative correlation with the intergranular volume (R2 = 0.97) (Fig. 5b3, b4). It also positively correlates with the compactional index (R2 = 0.90, R2 = 0.84) (Fig. 5c3, c4), while a correlation with optical porosity and ECR remain indistinct (Fig. 5d3, d4).

Cross-plots of petrographic parameters, with selected parameters plotted against optical porosity, IGV, grain-to-grain coatings and grain-to-IGV coatings. Linear lines of best fit indicate correlations and the corresponding R2. Correlations on porosity, quartz cement and ECR would improve if the Cornberg Sandstones preserving early carbonate cements would not be considered. ECR Effective contact ratio, IGV intergranular volume, GTG grain-to-grain, GTI grain-to-IGV

Samples with higher porosities show higher quantities of quartz cements (Fig. 5a1). Samples from northern England (PS) show the highest amount of quartz cements while simultaneously having the lowest grain-to-IGV coatings (Fig. 5a4). Sandstones from the Flechtingen High (FS) show the smallest amounts of quartz cements while having the highest grain-to-IGV coating coverage in this data set. Outlying Cornberg Sandstones (CS) samples show dolomite cementation (Fig. 3d). Optical porosity and grain-to-IGV coatings show no clear correlation (Fig. 5d4) due to the increased abundance of pore-filling dolomite and illite in Cornberg Sandstone samples (Table 2). Penrith Sandstone samples show highest porosities (Table 3), lowest grain-to-IGV coating coverage (Table 3) and highest amount of quartz cements (Table 2).

Density shows a negative correlation with optical porosity (R2 = 0.80, Fig. 6b2) and with IGV (R2 = 0.71, Fig. 6a2). It has a positive correlation with the compactional index (R2 = 0.62, Fig. 6c2), the total clay fraction (R2 = 0.71, Fig. 6d2) grain-to-grain coatings (R2 = 0.69, Fig. 6 e2), and with grain-to-IGV coatings (R2 = 0.54, Fig. 6f2), and the ECR (R2 = 0.89, Fig. 6g2). Amounts of total clays in both Flechtingen and Cornberg Sandstones are similar (Tables 2, 3), while IGV is ~ 50% larger for Cornberg samples (Table 3). This results in a correlation coefficient below 0.5 between IGV and total clay (Fig. 5b2).

Cross-plots of all geotechnical parameters on the x-axis compared to selected petrographic parameters on the y-axis. Linear lines of best fit indicate correlations with R2 > 0.7 and the corresponding R2. Correlations on IGV and coatings with mechanical parameters would improve if the diagenetic difference of preserved early carbonate cements of Cornberg samples would be considered as outliers. UCS Uniaxial compressive strength, E Young’s modulus, ε strain at failure

Mechanical correlations

Young’s modulus correlates well with UCS (R2 = 0.92, Fig. 4b1) and density (R2 = 0.92, Fig. 4b2). Similarly, rock density correlates with compressive strength (R2 = 0.89, Fig. 4b3). Strain does not correlate with compressive strength (Fig. 4a1), E (Fig. 3a2) or bulk density (Fig. 4a3).

Correlations between petrographic and mechanical parameters

The rock strength shows a negative correlation with the intergranular volume (R2 = 0.66, Fig. 6a1) and a negative correlation with optical porosity (R2 = 0.96, Fig. 6b1). The rock strength relates positively to the total clay fraction (R2 = 0.90, Fig. 6d1) and the distribution of authigenic clay coats on detrital quartz grains. The amount of illite coats along the grain-to-grain contacts show a reasonable correlation (R2 = 0.61, Fig. 6e1), while the illite coats along the grain-to-IGV do not correlate (R2 = 0.44, Fig. 6f1). The effective contact ratio shows a positive correlation with rock strength (R2 = 0.94, Fig. 6g1).

The Young’s modulus shows a positive correlation with the total clay fraction (R2 = 0.76, Fig. 6d3) and a negative correlation with the IGV (R2 = 0.53, Fig. 6a3). It correlates negatively with optical porosity (R2 = 0.90, Fig. 6b3). A correlation with the compactional index (R2 = 0.42, Fig. 6c3) and grain-to-grain coatings is indistinct (R2 = 0.47, Fig. 6e3). The effective contact ratio shows a positive correlation with Young’s modulus (R2 = 0.88, Fig. 6g3). Strain shows no correlation with any of shown petrographic parameters (Fig. 6a4–g4), which is further explored in the discussion.

The rock strength index ranges from 0.035 to 0.420 (Table 3), and shows positive correlations with the uniaxial compressive strength (R2 = 0.97), Young’s modulus (R2 = 0.94) and density (R2 = 0.85) (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Petrology and diagenesis

The assessment of detrital and authigenic phases, as well as mechanical and chemical compaction and their documented impact on the modification of the pore space, over geologic time scales, is the basis for the evaluation of the mechanical properties relevant at reservoir timescales. Here, the variations and implications of different rock types, as a function of different provenances, cementation and compaction, as a function of different burial histories are discussed for the presented samples.

Impact of petrology

A positive correlation exists between the IGV and porosity (Fig. 5d2), if Cornberg samples are not considered (R2 = 0.97). Similarly, the compactional index based on Lundegard (1992) correlates well with the optical porosity (R2 = 0.91) when Cornberg Sandstones are excluded (Fig. 5c1). The preservation of early carbonate cementation limited to Cornberg Sandstones, preventing mechanical compaction, (Fig. 3) is interpreted to be responsible for these outliers.

Impact of chemical compaction

Higher coverages of illitic grain-to-grain coatings at quartz–quartz interfaces are a major control of chemical compaction due to electrochemical potential differences on quartz–illite/muscovite–quartz interfaces (Greene et al. 2009; Kristiansen et al. 2011; Monsees et al. 2020). This is supported by the negative correlation between the compactional index and IGV (Fig. 5c2). The negative correlation between grain-to-grain coatings and quartz cement (Fig. 5c3) is interpreted as side-effect of the reduction of the IGV by compaction (Fig. 5c2), leading to less potential cement volume, which is also supported by the positive correlation between IGV and quartz cements (Fig. 5d2).

Impact of cementation

Smaller grain-to-IGV coating coverages are interpreted to control the IGV (Fig. 5b4) by enhancing syntaxial quartz cementation [e.g. Busch et al. 2017]. This results in a stabilization of the grain fabric and subsequently less mechanical compaction. The link between mechanical compaction and the reduction of pore-filling cementation is also demonstrated by the correlation between the compactional index after Lundegard (1992) and grain-to-IGV coatings (Fig. 5c4).

The unique diagenetic feature of Cornberg Sandstone compared to the other samples of this study is the abundant preservation of early carbonate cements, which are still present in subsurface equivalents of Flechtingen Sandstone (Mumm and Wolfgramm 2002) and Penrith Sandstone (Turner et al. 1995). Minor amounts of mouldic pores in authigenic quartz cement (Fig. 3c) were attributed to dolomite cement dissolution and occasionally occur in Penrith Sandstone (Busch et al. 2017), however they were not encountered during point-counting. Similarly, authigenic calcite in Flechtingen Sandstone samples as reported by Fischer et al. (2012) were not encountered during point-counting in the studied samples.

Impact on porosity

The apparent contradiction between highest amounts of quartz cements and highest porosities highlights its dependence of the IGV on several parameters. Therefore, the degree of compaction represented by compactional indices ranging from 0.2 to 0.8 and IGVs ranging from 17.0 to 40.7% are identified as one of the main controls on the porosity evolution. Porosity is generally reduced with reducing IGV (Paxton et al. 2002). IGVs in quartz sandstones are exponentially reduced during burial up to 26% by mechanical loading due to ideal packing of spherical grains, assuming well sorting and no major detrital clay (< 5%) as boundary conditions (Paxton et al. 2002). The sandstone composition in this study matches these criteria (Tables 2, 3). IGVs as low as 17% indicate that chemical compaction on long grain contacts took place, which is reflected by the increase in ECR for samples with lowest IGV (Fig. 5f2) and highest grain-to-grain illite coatings (Fig. 5f3) (Monsees et al. 2020).

Studies from natural sandstones show an influence of median grain size on porosity ranging from very significant to completely insignificant (Baud et al. 2014; Bell 1978; David et al. 1998; Fahy and Guccione 1979; Taylor et al. 2010). This has been explained by the influence of porosity, detrital and authigenic components and various amounts of compaction (McKinley et al. 2011; Morad et al. 2010). The control on optical porosity in this study is the sum of detrital and authigenic clay based on linear regression analysis (Fig. 5b1), showing the expected negative correlation with optical porosity due to the ductile properties of clay. Median grain size is not a controlling factor on porosity in this study (Fig. 5d1). Detrital composition also does not have a clear impact on the porosity evolution in this data set, because Cornberg and Penrith Sandstones with very similar detrital composition (Fig. 3h) show large porosity differences (Fig. 5a–f1).

Diagenesis and geomechanical rock properties

Since diagenesis, as a function of provenance, mechanical and geochemical alteration modifies the pore structure and particle contacts over geological timescales, the diagenetic contribution to present day measured geomechanical properties, relevant for production timescales, should be derivable. Positive correlations between UCS, Young’s modulus and rock density (Fig. 3) are well established elsewhere (Dobereiner 1986; Shakoor and Bonelli 1991). UCS, Young’s modulus and bulk density consistently show similar trends when plotted against the petrographic proxies IGV, optical porosity, compactional index, clay content, GTG and GTI coatings, and effective contact ratio (Fig. 6), however correlation coefficients vary.

Impact of chemical compaction

Grain size in artificial pure sandstones (quartz arenite) without chemical compaction correlates well with UCS (Atapour and Mortazavi 2018). Chemical compaction is driven by (i) the amount of overburden, temperature, and fluid pressure i.e. the effective stress and the amount and size of quartz grains, and is reflected by the type of quartz grain contacts (Bjørlykke and Høeg 1997; Renard et al. 1997), and (ii) the extent of clay coating on rigid quartz along quartz–quartz contacts driving pressure solution (Greene et al. 2009; Kristiansen et al. 2011; Monsees et al. 2020).

Impact of porosity

Optical porosity seems to control UCS (Fig. 6b1) and density (Fig. 6b2) due to lower strength and densities (Atapour and Mortazavi 2018; Baud et al. 2014; Hsieh et al. 2008; Weng et al. 2005). Thus, the reduction of porosity and the increase of the effective contact ratio (ECR) during diagenesis need to be constrained to assess rock strength in context of diagenetic alterations.

Impact of cementation

Cross-plots between geotechnical parameters and individual authigenic minerals such as quartz cements yielded no conclusive results. However, using the intergranular volume as the sum of intergranular porosity and cements, samples with less IGV, thus more heavily compacted, show higher UCS (Fig. 6a1), Young’s modulus (Fig. 6a2) and densities (Fig. 6a2). This is interpreted to be due to the fraction of intergranular porosity, which leads to lower rock strength and density, and due to authigenic minerals, also contributing to the IGV. The observed negative correlation between UCS and clay content (Fig. 6d1) seems counter-intuitive, implying a higher clay content in sandstones would result in higher strength. Similar negative correlations have been reported in weak sandstones with UCS < 20 MPa (Chen and Hu 2003); however, they were limited to the same rock type. The negative correlation in this study is due to CS and FS samples being either significantly more cemented (CS) with higher clay contents, or more compacted and cemented (FS), while PS samples show higher IGVs, higher optical porosities, and lower UCS (Fig. 6a1, b1, e1).

Impact of clay coatings

Clay coatings seem to exhibit a small to intermediate control on geomechanical properties. Illitic grain coatings can inhibit syntaxial quartz cementation but may drive chemical compaction (Busch et al. 2020; Monsees et al. 2020). Consequently, the absence of illitic grain coatings favors early syntaxial cementation, thus reducing the effect of mechanical compaction. These processes are reflected by the GTG and GTI coating analyses (Monsees et al 2020) and the compactional index (Lundegard 1992), respectively.

Grain-to-grain coating clay increases the density (Fig. 6e2) due to their inferred control on chemical compaction (Fig. 5c3) (Monsees et al. 2020), subsequently also enhancing the UCS (Fig. 6e1) and E (Fig. 6e3). The correlation of grain-to-IGV coatings with density is barely meaningful (Fig. 6f2) and implies that more quartz cementation results in lower density, as GTI coatings were observed to exhibit a control on quartz cementation (Fig. a4). The IGVs are higher in the sample group with the highest amounts of quartz cements (PS, see Fig. 5d2), as a result the counter-intuitive positive correlation between GTI coatings and density is due to less compaction, and thus less reduction of potential porosity [e.g. Paxton et al. (2002)]. Correlations of GTI coatings with UCS (Fig. 6f1) and E (Fig. 6f3) show the same positive trend due to the good correlation between UCS, E and density (Fig. 3b1–3); however, their correlation coefficients consistently are around or below R2 = 0.5.

Implications for deformation

No linear correlation of strain at failure (ε) with any of the petrographic proxies could be established (Fig. 6). However, there seems to be a logarithmic relationship between ε and the ratio of IGV/compactional index (Fig. 6a4, c4) if the outlier in the upper right (sample PS3 from quarry B, see chapter 3) would be removed. Similar observations were made for the plots comparing ε and grain-to-grain coatings (Fig. 6e4, f4), if sample PS3 would be excluded. The resulting correlation coefficients would be around R2 = 0.7 for Fig. 6a4, c4, f4 and around R2 = 0.85 for Fig. 6e4. This would result in inelastic deformation represented by ε being controlled by grain-to-grain coatings (Fig. 6f4), which would be in agreement with recent research on inelastic deformation of reservoir sandstones (Pijnenburg et al. 2019b), resulting in implications for induced seismicity (Pijnenburg et al. 2019a).

The higher porosity and resulting lower rock strength of sample PS3 due to being less compacted result in stronger displacement, explaining the higher ε compared to the possible strain-petrography relationship discussed here. Consequently, this would infer that this proposed relationship between strain at failure (ε) and the ratio of IGV/compaction index is only valid for sandstones that have undergone a certain amount of compaction and porosity reduction. UCS and E were determined in the same experiment as ε and showed consistent results.

Implications for the rock strength index

The rock strength in sandstones increases with the amount of porosity reduction (Fig. 6b1) and increases with higher effective contact ratios between grains and cements (Fig. 6g1). Both mechanical and chemical compactions reduce porosity and increase rock strength (Bjørlykke and Høeg 1997). As both porosity (Fig. 6b1) and effective contact ratios between particles (Fig. 6g1) were shown to correlate with mechanical properties, we propose to calculate a rock strength index SR for the samples in this study (Fig. 7). The rock strength index shows a linear relationship for the tested UCS range from 3 to 60 MPa in the presented data set (Fig. 7), and enables a first-order UCS, density and Young’s modulus estimation based on petrographic data.

Implications for reservoir timescale

All interactions between parameters described so far can be categorized on the geologic and the reservoir timescale. The geologic timescale features processes of porosity reduction and compaction increasing rock strength, reflected by the effective contact ratio of grain contacts (Fig. 6g1), and decrease in porosity (Fig. 6b1).

On the reservoir timescale, the mechanical rock properties are related to cementation and chemical compaction, which are reflected by the effective contact ratio and rock strength index SR (Fig. 8). Larger cement volumes and enhanced chemical compaction both increase the effective contact ratio, thus reflecting the impact of diagenesis. The importance of clay mineral coatings in sandstones on reservoir timescales has been well established from geomechanical experiments (Pijnenburg et al. 2019b), while the quantification of this effect in heterogeneous sandstones may not universally applicable as presented in this study.

Schematic overview of the effect of diagenetic alterations on optical porosity and geomechanical properties. The geologic setting controls the initial parameters such as composition and depositional environment, as well as boundary conditions like temperature, pressure, ion availability etc. Each correlation line symbolizes a positive correlation e.g. if the uniaxial strength is high, Young’s modulus is also high. Each anti-correlation line symbolizes a negative correlation, eg. if optical porosity is high, then uniaxial compressive strength is low. Effective contact lengths (Fig. 2) are increased by all compaction and cementation processes. GTI Grain-to-IGV, GTG grain-to-grain, pf pore-filling

Conclusions

The studied Rotliegend sandstones represent fluvio-eolian depositional environments mostly comprised of detrital quartz with close to no detrital clay component. Due to different diagenetic histories, their corresponding diagenetic alterations and porosity is different. Authigenic quartz is the major diagenetic phase in all samples. Cornberg Sandstones show intermediate compaction and high cementation, Flechtingen Sandstones experienced a high amount of compaction and intermediate cementation, while Penrith Sandstones show low compaction and intermediate cementation.

Mechanical compaction was observed to be dependent on the abundance of pore-filling rigid authigenic minerals like carbonates and quartz stabilizing the grain-framework. Chemical compaction was assessed based on the illite coverages on grain-to-grain interfaces. Generally, higher compaction induced a porosity reduction depending on the different sample groups and diagenetic pathways. The presence of preserved early carbonate cementation in Cornberg samples was identified as a reason for outliers when assessing the petrographic properties in comparison to mechanical properties. Such different diagenetic evolution of similar sandstones might explain generally well working correlations in artificial (pure) sandstones compared to contradicting studies featuring natural, heterogeneous specimens.

Optical porosity was identified as the main control on UCS, Young’s modulus and density with a pronounced negative correlation (R2 > 0.80). Optical porosity is controlled by diagenetic alterations in this study, namely authigenic quartz, dolomite and clay minerals together with mechanical and chemical compaction. Chemical compaction is dependent on the spatial relationships and abundance of grain-coating clay minerals and detrital and authigenic quartz.

The length of horizontal grain contacts normalized to the individual grain size relates grain fabric to mechanical properties. Effective contact ratios show positive correlations with UCS (R2 = 0.97), Young’s modulus (R2 = 0.94) and density (R2 = 0.85). Such petrography-based rock strength index including porosity and effective contact ratio may be tested for other study areas.

The results of this study help to understand and quantify the relation between diagenetic parameters and geomechanical properties utilizing the rock strength index representing the sum of diagenetic influence on porosity reduction and grain connectivity orientated to the stress conditions. Consequently, they may be applied as first-order estimate of mechanical properties for sandstones with similar boundary conditions, if sufficiently large specimen for geotechnical standard tests are not obtainable.

References

Aagaard P, Jahren JS, Harstad AO, Nilsen O (2000) Formation of grain-coating chlorite in sandstones. Laboratory synthesized vs. natural occurrences. Clay Min 35:261–269

Aehnelt M, Katzung G (2007) Das Rotliegende im Richelsdorfer Gebirge-Stratigraphie, Lithologie und Paläogeographie. Geol Jb Hessen 134:5–36

Ambrose WA, Lakshminarasimhan S, Holtz MH, Núñez-López V, Hovorka SD, Duncan I (2008) Geologic factors controlling CO2 storage capacity and permanence: case studies based on experience with heterogeneity in oil and gas reservoirs applied to CO2 storage. Environ Geol 54:1619–1633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-007-0940-2

Arthurton RS, Wadge AJ (1981) Geology of the country around Penrith, vol 24. Institute of Geological Sciences, Natural Environment Research Council, Swindon

Atapour H, Mortazavi A (2018) The influence of mean grain size on unconfined compressive strength of weakly consolidated reservoir sandstones. J Petrol Sci Eng 171:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2018.07.029

Bachu S (2000) Sequestration of CO2 in geological media: Criteria and approach for site selection in response to climate change. Energy Convers Manage 41:953–970. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-8904(99)00149-1

Barnard PL, Rubin DM, Harney J, Mustain N (2007) Field test comparison of an autocorrelation technique for determining grain size using a digital ‘beachball’ camera versus traditional methods. Sed Geol 201:180–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2007.05.016

Baud P, Wong TE, Zhu W (2014) Effects of porosity and crack density on the compressive strength of rocks. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 67:202–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2013.08.031

Becker I, Wüstefeld P, Koehrer B, Felder M, Hilgers C (2017) Porosity and permeability variations in a tight gas sandstone reservoir analogue, Westphalian D, Lower Saxony Basin, NW Germany: influence of depositional setting and diagenesis. J Pet Geol 40:363–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpg.12685

Becker I, Busch B, Koehrer B, Adelmann D, Hilgers C (2019) Reservoir quality evolution of Upper Carboniferous (Westphalian) tight gas sandstones, Lower Saxony Basin, NW Germany. J Pet Geol 42:371–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpg.12742

Bell FG (1978) The physical and mechanical properties of the Fell Sandstones, Northumberland, England. Eng Geol 12:1–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-7952(78)90002-9

Bjørlykke K, Høeg K (1997) Effects of burial diagenesis on stresses, compaction and fluid flow in sedimentary basins. Mar Pet Geol 14:267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8172(96)00051-7

Busch B, Hilgers C, Gronen L, Adelmann D (2017) Cementation and structural diagenesis of fluvio-aeolian Rotliegend sandstones, northern England. J Geol Soc 174:855–868. https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2016-122

Busch B, Hilgers C, Lander RH, Bonnell LM, Adelmann D (2018) Reservoir quality and burial model evaluation by kinetic quartz and illite cementation modeling: case study of Rotliegendes, north Germany. AAPG Bull 102:293–307. https://doi.org/10.1306/0503171605217075

Busch B, Hilgers C, Adelmann D (2020) Reservoir quality controls on Rotliegend fluvio-aeolian wells in Germany and the Netherlands, Southern Permian Basin—impact of grain coatings and cements. Mar Pet Geol 112:104075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.104075

Chang C, Zoback MD, Khaskar A (2006) Empirical relations between rock strength and physical properties in sedimentary rocks. J Petrol Sci Eng 51:223–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2006.01.003

Chen H, Hu Z-Y (2003) Some factors affecting the uniaxial strength of weak sandstones. Bull Eng Geol Env 62:323–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-003-0207-4

David C, Menéndez B, Bernabé Y (1998) The mechanical behaviour of synthetic sandstone with varying brittle cement content. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 35:759–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-9062(98)00003-5

DIN18136 (2003) Investigation and testing—Unconfined compression test. DIN German Institute for Standardization, Germany

Dobereiner L (1986) Geotechnical properties of weak sandstones. Géotechnique 36:79–94. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1986.36.1.79

Dyke CG, Dobereiner L (1991) Evaluating the strength and deformability of sandstones. Q J Eng Geol Hydrogeol 24:123–134. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.QJEG.1991.024.01.13

Fahy MP, Guccione MJ (1979) Estimating strength of sandstone using petrographic thin-section data. Environ Eng Geosci 16:467–485. https://doi.org/10.2113/gseegeosci.xvi.4.467

Fischer C, Dunkl I, von Eynatten H, Wijbrans JR, Gaupp R (2012) Products and timing of diagenetic processes in Upper Rotliegend sandstones from Bebertal (North German Basin, Parchim Formation, Flechtingen High, Germany). Geol Mag 149:827–840. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756811001087

Folk RL (1980) Petrology of the sedimentary rocks. Hemphill Publishing Company, Austin. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-555X(91)90027-8

Gaitzsch B, Geißler M, Göthel M, Kopp J, Legler B (2004) Karbon und Rotliegend der Flechtingen-Roßlau-Scholle. In: Friedel C-H, Röhling H-G (eds) GeoLeipzig 2004 - Geowissenschaften sichern Zukunft, vol 35. Deutsche Geologische Gesellschaft, Hannover, pp 150–164

Gast RE (1994) Cornberg outcrops revisited (Hessen, Germany): the depositional environment of its saurian tracks and Weissliegend Sandstones. Meyniana 46:59–75

Gast RE et al (2010) Rotliegend. In: Doornenbaal H, Stevenson A (eds) Petroleum geological atlas of the southern permian Basin area. EAGE, Houten, pp 101–121

Gaupp R, Matter A, Platt J, Ramseyer K, Walzebuck J (1993) Diagenesis and fluid evolution of deeply buried Permian (Rotliegende) gas reservoirs, northwest Germany. AAPG Bull. https://doi.org/10.1306/BDFF8E0C-1718-11D7-8645000102C1865D

Ghassemi A (2012) A Review of some rock mechanics issues in geothermal reservoir development. Geotech Geol Eng 30:647–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-012-9508-3

Greene GW, Kristiansen K, Meyer EE, Boles JR, Israelachvili JN (2009) Role of electrochemical reactions in pressure solution. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 73:2862–2874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2009.02.012

Hettema MHH, Schutjens PMTM, Verboom BJM, Gussionklo HJ (2000) Production-induced compaction of a sandstone reservoir: the strong influence of stress path. SPE Reserv Eval Eng 3:342–347. https://doi.org/10.2118/65410-PA

Houseknecht DW (1987) Assessing the relative importance of compaction processes and cementation to reduction of porosity in sandstones. AAPG Bull 71:633–642. https://doi.org/10.1306/9488787F-1704-11D7-8645000102C1865D

Hsieh Y-M, Li H-H, Huang T-H, Jeng F-S (2008) Interpretations on how the macroscopic mechanical behavior of sandstone affected by microscopic properties—revealed by bonded-particle model. Eng Geol 99:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2008.01.017

Jackson DI, Johnson H, Smith NJP (1997) Stratigraphical relationships and a revised lithostratigraphical nomenclature for the Carboniferous, Permian and Triassic rocks of the offshore East Irish Sea Basin. Geol Soc Lond Spec Pub 124:11–32. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1997.124.01.02

Kowalczyk G, Herbst A, Heggemann H (2012) Rotliegend in den Hessischen Becken. In: Lützner H, Kowalczyk G (eds.). Stratigraphie von Deutschland X. Rotliegend. Teil I: Innervariscische Becken. vol 61. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften, Hannover, pp 378–417. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1127/sdgg/61/2012/378

Kristiansen K, Valtiner M, Greene GW, Boles JR, Israelachvili JN (2011) Pressure solution—the importance of the electrochemical surface potentials. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 75:6882–6892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.09.019

Kulick J, Leifeld D, Meisl S (1984) Petrofazielle und chemische Erkundung des Kupferschiefers-der Hessischen Senke und des Harz-Westrandes. vol 68. Geologisches Jahrbuch Reihe D. Schweizerbart, Hannover

Lander RH, Larese RE, Bonnell LM (2008) Toward more accurate quartz cement models: the importance of euhedral versus noneuhedral growth rates. AAPG Bull 92:1537–1563. https://doi.org/10.1306/07160808037

Legarth B, Huenges E, Zimmermann G (2005) Hydraulic fracturing in a sedimentary geothermal reservoir: results and implications. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 42:1028–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2005.05.014

Lundegard PD (1992) Sandstone porosity loss; a “big picture” view of the importance of compaction. J Sediment Petrol 62:250–260. https://doi.org/10.1306/D42678D4-2B26-11D7-8648000102C1865D

Macchi LC (1981) Sedimentology of the Penrith sandstone and Brockrams (Permo-Triassic) of Cumbria, north-west England. University of Hull, England

McKinley JM, Atkinson PM, Lloyd CD, Ruffell AH, Worden RH (2011) How porosity and permeability vary spatially with grain size, sorting, cement volume, and mineral dissolution in fluvial Triassic sandstones: the value of geostatistics and local regression. J Sediment Res 81:844–858. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2011.71

Menning M (1995) A numerical time scale for the Permian and Triassic periods: an integrated time analysis. In: Scholle PA, Peryt TM, Ulmer-Scholle DS (eds) The Permian of northern pangea vol paleogeography paleoclimates stratigraphy, vol 1. Springer, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-78593-1_6

Moeck I, Schandelmeier H, Holl HG (2009) The stress regime in a Rotliegend reservoir of the Northeast German Basin. Int J Earth Sci 98:1643–1654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-008-0316-1

Monsees AC, Busch B, Schöner N, Hilgers C (2020) Rock typing of diagenetically induced heterogeneities—a case study from a deeply-buried clastic Rotliegend reservoir of the Northern German Basin. Mar Petrol Geol 113:104163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.104163

Morad S, Al-Ramadan K, Ketzer JM, De Ros LF (2010) The impact of diagenesis on the heterogeneity of sandstone reservoirs: a review of the role of depositional facies and sequence stratigraphy. AAPG Bull 94:1267–1309. https://doi.org/10.1306/04211009178

Mumm AS, Wolfgramm M (2002) Diagenesis and fluid mobilisation during the evolution of the North German Basin—evidence from fluid inclusion and sulphur isotope analysis. Mar Pet Geol 19:229–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8172(02)00015-6

Mutschler T (2004) Neufassung der Empfehlung Nr. 1 des Arbeitskreises “Versuchstechnik Fels” der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geotechnik e. V.: Einaxiale Druckversuche an zylindrischen Gesteinsprüfkörpern. Bautechnik 81:825–834. https://doi.org/10.1002/bate.200490194

Otto V (2003) Inversion-related features along the southeastern margin of the North German Basin (Elbe Fault System). Tectonophysics 373:107–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-1951(03)00287-7

Paul J (2012) Weißliegend, Grauliegend und das Zechstein-Konglomerat: die Rotliegend/Zechstein-Grenze. In: Lützner H, Kowalczyk G (Eds.). Stratigraphie von Deutschland X. Rotliegend. Teil I: Innervariscische Becken. vol 61. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften, Hannover, pp 707–714. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1127/sdgg/61/2012/707

Paxton ST, Szabo JO, Ajdukiewicz JM, Klimentidis RE (2002) Construction of an intergranular volume compaction curve for evaluating and predicting compaction and porosity loss in rigid-grain sandstone reservoirs. AAPG Bull 86:2047–2067. https://doi.org/10.1306/61EEDDFA-173E-11D7-8645000102C1865D

Pijnenburg RPJ, Verberne BA, Hangx SJT, Spiers CJ (2019a) Inelastic deformation of the Slochteren sandstone: stress-strain relations and implications. JGR Solid Earth 124:5254–5282. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JB017366

Pijnenburg RPJ, Verberne BA, Hangx SJT, Spiers CJ (2019b) Intergranular clay films control inelastic deformation in the Groningen gas reservoir: evidence from split-cylinder deformation tests. JGR Solid Earth 124:12679–12702. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JB018702

Pryor AW (1971) Petrology of the Weißliegendes sandstones in the Harz and Werra-Fulda area. Geol Rundsch 80:524–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02000468

Regenspurg S, Feldbusch E, Byrne J, Deon F, Driba DL, Henninges J, Kappler A, Naumann R, Reinsch T, Schubert C (2015) Mineral precipitation during production of geothermal fluid from a Permian Rotliegend reservoir. Geothermics 54:122–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geothermics.2015.01.003

Renard F, Ortoleva P, Gratier JP (1997) Pressure solution in sandstones: influence of clays and dependence on temperature and stress. Tectonophysics 280:257–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-1951(97)00039-5

Sayers CM, Schutjens PMTM (2007) An introduction to reservoir geomechanics. Lead Edge. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.2737100

Schmidt C, Busch B, Hilgers C (2020) Compaction and cementation control on bleaching in Triassic fluvial red beds. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften, S-Germany. https://doi.org/10.1127/zdgg/2020/0233

Schneider J, Gebhardt U (1993) Litho- und Biofaziesmuster in intra- und extramontanen Senken des Rotliegend (Perm, Nord- und Ostdeutschland). Geologisches Jahrbuch A 131:57–98

Schröder L, Plein E, Bachmann G-H, Gast RE, Gebhardt U, Graf R, Helmuth H-J, Pasternak M, Porth H, Süssmuth S (1995) Stratigraphische Neugliederung des Rotliegend im Norddeutschen Becken. Geol Jahrb 148:3–21

Schumacher C (1985) Die Kupfervererzungen des basalen Zechsteins im Rahmen der sedimentären Entwicklung des Werra-Fulda-Beckens. FU Berlin

Shakoor A, Bonelli RE (1991) Relationship between petrographic characteristics, engineering index properties, and mechanical properties of selected sandstones. Environ Eng Geosci 28:55–71. https://doi.org/10.2113/gseegeosci.xxviii.1.55

Talwani P, Acree S (1985) Pore pressure diffusion and the mechanism of reservoir-induced seismicity. In: Shimazaki K, Stuart W (Eds.). Earthquake Prediction. Pure and applied geophysics. Birkhäuser Basel, Switzerland. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-0348-6245-5_14

Taylor JM (1950) Pore-space reduction in sandstones. AAPG Bull 34:701–716. https://doi.org/10.1306/3D933F47-16B1-11D7-8645000102C1865D

Taylor TR, Giles MR, Hathon LA, Diggs TN, Braunsdorf NR, Birbiglia GV, Kittridge MG, MacAulay CI, Espejo IS (2010) Sandstone diagenesis and reservoir quality prediction: models, myths, and reality. AAPG Bull 94:1093–1132. https://doi.org/10.1306/04211009123

Trask PD (1930) Mechanical analyses of sediments by centrifuge. Econ Geol 25:581–599. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.25.6.581

Turner P, Burley SD, Rey D, Prosser J (1995) Burial history of the Penrith Sandstone (Lower Permian) deduced from the combined study of fluid inclusion and palaeomagnetic data. In: Turner P, Turner A (Eds.). Palaeomagnetic Applications in Hydrocarbon Exploration and Production, vol 98. Geol. Soc. Spec. Pub., pp 43–78. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1995.098.01.04

Ulusay R, Türeli K, Ider MH (1994) Prediction of engineering properties of a selected litharenite sandstone from its petrographic characteristics using correlation and multivariate statistical techniques. Eng Geol 38:135–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-7952(94)90029-9

Weng MC, Jeng FS, Huang TH, Lin ML (2005) Characterizing the deformation behavior of Tertiary sandstones. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 42:388–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2004.12.004

Worden RH, Armitage PJ, Butcher A, Churchill J, Csoma A, Hollis C, Lander R, Omma J (2018) Petroleum reservoir quality prediction : overview and contrasting approaches from sandstone and carbonate communities. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 435:1–31. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP435.21

Wüstefeld P, Hilse U, Lüders V, Wemmer K, Koehrer B, Hilgers C (2017) Kilometer-scale fault-related thermal anomalies in tight gas sandstones. Mar Pet Geol 86:288–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2017.05.015

Zoback MD, Zinke JC (2002) Production-induced normal faulting in the Valhall and Ekofisk oil fields. In: Trifu CI (ed) The mechanism of induced seismicity. Pageoph Topical Volumes, Birkhäuser, Basel, pp 403–420

Zorlu K, Gokceoglu C, Ocakoglu F, Nefeslioglu HA, Acikalin S (2008) Prediction of uniaxial compressive strength of sandstones using petrography-based models. Eng Geol 96:141–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2007.10.009

Acknowledgements

Editor-in-Chief Olaf Kolditz and two anonymous reviewers are thanked for their constructive comments, which greatly improved the manuscript. The municipality of Cornberg is thanked for access to the quarry and logistical assistance. Cumbria Quarry Services Ltd. is thanked for access and logistical support. Access to the decommissioned quarry on private property is thankfully acknowledged. D. Soyk and S. Kuchling (DGMK) are thanked for project coordination.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge research funding by the BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research, research grant: FKZ 03G0868A). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is a part of the Topical Collection in Environmental Earth Sciences on “Sustainable Utilization of Geosystems” guest edited by Ulf Hünken, Peter Dietrich and Olaf Kolditz.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Monsees, A.C., Biebricher, S.F., Busch, B. et al. Coupling of diagenetic alterations and mechanical properties of Lower Permian siliciclastic sandstones: a pilot study. Environ Earth Sci 80, 141 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-021-09376-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-021-09376-1