Abstract

Purpose of review

Metastatic breast cancer (MBC) was traditionally viewed as homogeneously progressive and incurable among all comers, but there is new evidence that MBC harbors a range of tumor molecular/immune subtypes and degrees of aggressiveness. Thus, MBC is not rapidly fatal in all affected patients.

Recent findings

A small subset of patients will attain long-term disease control, or undetectable disease, and will enjoy a prolonged survival with little disability from their disease or treatment. Though the term is controversial, some patients with long-term non-detectable disease may effectively be considered “cured”. To best advise treatment options in these patients, it is imperative to identify patients most likely to benefit from aggressive treatment.

Summary

In this review, we delineate the clinical, pathologic, and disease characteristics associated with long-term non-progression in MBC. We include a single institution case series of long-term non-progressive MBC patients and their characteristics as an example of the frequency of this sub-population of MBC. Future prospective trials are warranted to examine the utility of clinical characteristics as predictors of long-term survival in MBC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Though there have been significant improvements in our understanding of breast cancer pathophysiology and in the development of novel therapeutics, breast cancer continues to be a leading cause of death for women. Metastatic disease accounts for over 90% of these deaths and has traditionally been thought of as incurable [1]. There is a small subset of patients who achieve long-term relapse-free survival after a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) [2, 3]. Overall, long-term non-progression accounts for up to 10% of metastatic disease in some series [4, 5]. For this report, long-term non-progression is defined as a period of at least five years for which metastatic disease remained clinically and radiographically without any growth in longest diameter of all metastatic lesions (a stricter definition than the RECIST definition of stability).

MBC has proven to be a heterogeneous collection of disease subtypes [6]. With the advent of a new era of Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 (HER2) targeted drugs as well as other novel targeted therapies, there is renewed importance in identifying those patients who are likely to benefit from aggressive treatment of their metastatic breast cancer up front. The goal of this project is to outline the clinical and biologic characteristics associated with non-progression in MBC and to consider those as predictors of outcome. These factors fall into three overarching categories: patient characteristics, pathologic characteristics, and biologic disease characteristics.

Case series on non-progression

An IRB exemption was granted (9/17/2020) to review case records of selected long-term non-progressing MBC patients at a tertiary academic hospital. MBC cases were limited to those which achieved radiographic evidence of disease disappearance or perfect stability for at least five years on a single therapy or with no systemic therapy. The clinical characteristics were tabulated. A minimum five-year follow-up was required (patients without clinical or radiographic follow-up were excluded). Records were reviewed from 2000 to present. Pathologic confirmation of metastatic breast cancer was required for inclusion (radiographic only MBC patients without biopsy confirmation were excluded). The final cohort included only some “exceptional responders” or patients who experienced complete or durable partial response more than 3 times the median response duration. Any exceptional responder who experienced disease recurrence before reaching the 5-year mark was excluded from this case series. The duration of non-progression was measured from the first scan with resolution/stability until 9/18/2020 or progression.

Given the limitations of retrospective data collection, a true incidence rate for long-term non-progression in a geographic catchment area was not feasible. Nevertheless, there were 16 patients that met the foregoing criteria for 5-year non-progression. For perspective, the institutional database identifies over 700 metastatic breast cancer patients with at least two visits to the institution over the same time period (not excluding second opinions, cases lost to follow-up, and unconfirmed diagnoses). The features of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. The median age of presentation was 46 years, with a range of 33 to 83 years old. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was low (median of 7.5). De novo MBC accounted for a quarter of the cases. HER2 positivity accounted for slightly more than half (56%) of this series; ER positivity was also noted in 56% of patients at the site of metastatic biopsy. Finally, half of the patients had oligometastatic disease (50%) which is in line with most other reports of long-term non-progression [3, 5, 7,8,9,10,11]. This patient series is slightly younger, and had slightly better Charlson Comorbidity scores than some recent case series. The impact of these observed clinical predictors as well as impacts of other predictors are reviewed below, with reference to relevant contemporary literature reports.

Characteristics of long-term non-progression

Age and performance status

In an institutional review of 168 long-term metastatic HER2 amplified breast cancer patients, Murthy et al. demonstrated that younger age at initial diagnosis was associated with significantly longer overall survival (OS) [10]. Similarly, a study by Greenberg et al. found that younger patients were significantly more likely to achieve complete response (CR) and to have longer progression free survival (PFS) [7]. Conversely, another study found that age >60 years was associated with shorter OS [12]. Our population of long-term non-progressors has a median age of breast cancer diagnosis of 46 years, much less than the median age of 62 years [13, 14].

A number of studies have shown that good performance status is associated with non-progression [4, 9, 10]. One study by Tomiak et al. found a significant association between survival and WHO performance status in both univariate and multivariate analysis [15]. In our own cohort, the median ECOG performance status was 0, further suggesting that better mobility upon diagnosis of MBC is associated with better outcomes.

Pathologic characteristics

Prior to the advent of targeted therapies, HER2 positive tumors were considered to be particularly aggressive with poor prognosis [16]. Since the advent of Trastuzumab, the first anti-HER2 drug, the median survival of HER2 positive metastatic breast cancer patients has increased over twofold [17]. While metastatic disease remains largely incurable, HER2 positive patients treated with targeted anti-HER2 therapy make up a significant portion of non-progressors [18]. This suggests that an excellent response to highly targeted therapies may play a role in long-term relapse-free survival. The Trastuzumab antibody also generates a robust immune response thus aiding in long-term responses against HER2 amplified cancer cells [19].

The rate of clinical CR is significantly higher in HER2-positive MBC patients compared to HER2 non-amplified patients, and is associated with better outcomes overall, further outlining the important role of HER2 positivity in attaining excellent treatment response [5]. Interestingly, patients who received adjuvant Trastuzumab prior to the development of metastatic disease have reduced OS compared to de novo metastatic HER2 patients who first receive Trastuzumab in the metastatic setting. Those pre-treated patients have been shown not to respond as well to re-exposure to anti-HER2 therapy [20]. Reasons for tepid responses to retreatment may involve pre-selection of a primarily resistant population, mutations in the HER2 receptor itself, down-regulation of the receptor and potential immune tolerance.

One study of a population of HER2-positive MBC patients found hormone receptor (HR) positivity to be an independent prognostic factor for longer PFS, demonstrating a 35% increase in median PFS and a higher likelihood of long-term survival (LTS) for HR-positive vs HR-negative patients. This study also noted a decreased likelihood for LTS patients to have received adjuvant Trastuzumab [20]. Interestingly, our patient population has close to equal numbers of HR+ and HR− patients.

While there is an association between long-term benefit of Trastuzumab-based therapy and HR positivity, HR sensitivity continues to have questionable predictive value in determining treatment outcomes for MBC patients [20]. Unfortunately, it is likely that such clinicopathological markers alone will not be sufficient to accurately identifying those patients who would receive marked benefit from anti-HER2 therapy, thus underscoring the importance of uncovering specific molecular markers to predict patient outcomes.

Tumor histology

Tumor histology, namely the classification of a tumor as ductal, luminal, or other, has a controversial effect on OS. Generally, in the setting of localized disease, the better prognostic histologic subtypes are thought to include tubular, mucinous, cribriform, medullary, and papillary, while the poor prognostic types include metaplastic, apocrine, micropapillary, and neuroendocrine. Even when limiting histology discussion to early stage ductal versus lobular types, the literature is rife with conflicting data on OS with some studies suggesting better survival in invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), while others indicate worse survival, and still others find the differences to be insignificant [21,22,23]. Generally, ILC is more often multicentric and bilateral compared to invasive ductal cancer (IDC) [24].

In the metastatic setting, it appears that ILC may be associated with worse prognosis than IDC, due to the propensity to spread to atypical visceral locations and to spread in occult patterns without mass formation [25, 26]. Intriguingly, circulating tumor cell counts are significantly higher in metastatic ILC [27]. This may possibly be explained by the lack of e-cadherin in those cells, and the propensity for them to infiltrate visceral membranes in a single file pattern. In the literature on long-term non-progression in breast cancer, there is no distinction identified to date between lobular and ductal cancers (p = 0.94 in the largest series), although datasets remain limited [18]. The proportion of patients achieving long-term non-progression mirrors the proportion of patients in the general population with ILC/IDC, but it is unclear if the two are related.

Tumor grade

Tumor grade is a well-established negative prognostic factor for metastatic breast cancer, owing at least in part to the propensity for grade 3 tumors to spread to visceral organs and to be associated with worse survival [28]. In a study evaluating a gene expression signature that differentiates between high- and low-grade tumors, “genetic tumor grade” was found to be a powerful independent risk factor for disease recurrence, on par with lymph node status and tumor size in several patient subgroups [29]. On the other hand, high grade tumors tend to be more susceptible to immunotherapies, owing to the propensity for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) to target tissues with high replication rates [30]. Unfortunately, in most circumstances, it appears that the heightened aggression of high grade tumors outweighs any increased benefit from ICI therapy. Specifically in the long-term no evidence of disease (NED) studies, grade was not found to predict for achievement of NED status (p = 0.987) [31].

Molecular profile

Breast cancer is molecularly driven by known and frequently recurring mutations. By profiling breast tumors, it is sometimes possible to predict response to targeted therapies [32]. It is also sometimes possible to predict exceptional responses and long-term non-progression. One of the first hints that molecular profiling could offer predictive and prognostic information to breast cancer came from the first IMPACT study of molecularly targeted novel therapies. In the trial, 1307 patients with advanced metastatic disease were profiled for targetable mutations. Half the patients were ultimately treated with molecularly matched agents and half were treated with non-matched drugs. The result was that response rates and OS were superior for the molecularly matched patients (Hazard Ratio 0.75, p < 0.001) [3]. Another piece of evidence that molecular profile might be relevant to outcome was observed in the first exceptional responders data analysis published in 2018 [2]. In that seminal report on exceptional responders, 59% had driver mutations for their cancer and 15% were breast cancer patients.

Additional support for the role of molecular profiling in exceptional responders derives from several case reports and case series. For example, there is a compelling case of a 39-year-old metastatic breast cancer patient with lung metastases (HR negative and HER2 positive) who was treated with nab-paclitaxel and Trastuzumab in 2009 [33]. This patient is an example of a patient with MBC who achieved no radiographic evidence of disease for greater than 8 years. Remarkably, there was concurrent achievement of no circulating tumor DNA as well [33]. This case is unique because the patient had p53, PIK3CA and DNMT3 mutations detectable at the time of high tumor burden disease, but once her systemic disease was successfully cytoreduced, her circulating tumor DNA assays also showed clearance of the mutations in blood samples. This case demonstrates the potential uses of circulating DNA technology to track potential residual microscopic disease in breast cancer, although it should be pointed out that as of 2020, such molecular monitoring is not yet considered standard of care.

Tumor microenvironment and immune biomarkers

There are wide differences in the immune regulation and genomic, proteomic and metabolomic signatures of the varying microenvironments where MBC cells find conditions favorable for growth. Even within the same organ type (i.e. bone) and within the same human, there may be variations in the pH, blood supply, macrophage, NK cell, T cell and cytokine milieu of differing metastatic deposits. Likewise, there are stark differences across different organs and across different breast cancer subtypes [6]. The immune biomarkers most predictive of excellent response to immunotherapy were recently reviewed and 9 were selected to be most predictive of long-term response. The presence or absence of such biomarkers suggests that some breast tumors are immunologically transparent while others may be recognized, but tolerized, while still others are recognized and ultimately immunologically attacked [33]. Currently the best evidence suggests that subsets of triple negative breast cancer may be the most amenable to immunotherapies, but this is a rapidly evolving field and subsets of ER+ and HER2 amplified disease are also potentially amenable to combinatorial therapy, including immunotherapy. Indeed, several trials combining ICI with HER2 targeted therapies, CDK4/6 inhibitors, or other targeted agents are ongoing. It is expected that some exceptional responders will emerge out of some of those studies, in part due to enhanced immunogenicity from combining immunotherapy with proven effective antineoplastic treatments.

Disease characteristics

A number of studies have shown that low systemic tumor load and a long disease-free interval before recurrence are associated with non-progression [4, 9, 10]. Other studies examining survival outcomes of breast cancer patients with metastases to the lung and liver found that long disease-free interval prior to pulmonary or hepatic metastasis was predictive of better outcomes [34,35,36]. Our patients also have a long median time to metastasis of 35 months, further suggesting that long disease-free intervals are associated with OS.

In a prospective cohort study of 3369 breast cancer patients without metastases receiving adjuvant treatment, it was found that patients with micrometastatic disease to the axillary lymph nodes had similar survival outcomes to those with macrometastatic disease to the nodes [37]. This might seem to suggest a limited role for tumor burden in predicting treatment outcomes, though this appears to only apply to pre-metastatic cancer. In a study of metastatic breast cancer patients by Kenneth et. al, there was a significant negative association between tumor burden and chemotherapy response rate, with an even more marked effect in the case of complete remissions. In this study, 38% of patients with low tumor burden (<5 metastatic lesions) achieved CR, compared to only 7% of those with high tumor burden (>20 metastatic lesions) [38]. Additionally, another study found that patients with low tumor burden and good performance status are more likely to achieve complete remission [7].

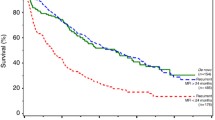

Achieving no evidence of disease (NED) status

NED status was a significant predictor of treatment outcomes in several reports. In one study of patients with MBC, 3- and 5-year OS rates were 44 and 24%, respectively, for the general patient population, compared to 96 and 78% for those attaining NED status. The study also showed a longer median survival for those with NED (112 vs 24 months for no NED). Moreover, there was a higher rate of NED status at 5 years in this modern series compared to prior investigations, possibly suggesting that newer agents played a part in enhancing treatment response [18]. Interestingly, hormone receptor positivity, de novo MBC, and oligometastasis were also associated with achieving NED status, further supporting its prognostic significance. In our population of non-progressors, 10 of the 16 patients achieved true NED status, while the rest achieved long-term stable sclerotic bone lesions.

Oligometastatic disease

While there is not yet an agreed-upon definition of oligometastasis in the literature, this term tends to denote metastasis to no more than 2 organs with no more than 5 metastatic lesions [39]. In one study of MBC patients, those with only one organ involved showed significantly higher CR/NED rates compared to those with 2 involved organs. 60.5% of those patients achieved CR with systemic therapy and 79.5% with multidisciplinary therapy [40]. Similarly, 43.8% of our long-term non-progressors have only 1 site of metastasis, much higher than the estimated 20% rate of oligometastasis among all MBC patients [41]. This further underscores the importance of oligometastasis as an independent prognostic factor for non-progression in MBC patients.

Metastasis to soft tissue and bone

It is well established in the literature that bone-confined MBC has a more indolent course and is associated with longer OS as compared to visceral disease [9, 39, 42]. Additionally, there are studies showing that patients with soft tissue metastases have better survival outcomes compared to those with other organ involvement [3, 9]. One study by Greenberg et al. found that achieving CR was more common with soft tissue metastases than it was for osseous metastases, though this may be confounded in part by the lack of tumor quantification when making site classifications [7]. Additionally, the sclerosis of bone that commonly occurs with osseous metastasis makes it difficult to determine when the cancer has fully regressed, further complicating outcome comparisons. Regardless, both osseous metastases and soft tissue metastases are associated with more favorable outcomes and have been linked to long-term survival in patients with HER2-positive MBC [3, 38].

De novo MBC

De novo MBC is estimated to occur in 18.2% of MBC patients [11]. Patients with de novo MBC also make up a significant proportion of non-progressors, with one study having as many as 32% of its long-term survivors present with de novo MBC [3]. Other studies have also found higher incidences of de novo MBC among their excellent responders [12]. In our patient cohort, 25% presented with de novo MBC. In one retrospective study of two institutions, 13% of patients with de novo HER2+ MBC achieved NED status with Trastuzumab-based therapy and those patients had very high PFS (100% at 5 and 10 years) and OS (98% at 5 and 10 years) [31].

Of note, a recent study of 16,187 patients by Plichta et al. advises the formal stratification of de novo stage IV breast cancer into 3 distinct prognostic groups based on the number of anatomic sites, receptor status, tumor “T stage” and tumor histologic grade. Based on their simple recursive partitioning analysis, there is a significant difference in the 3-year OS among the groups [43]. The “A” group of good prognostic features has a median OS of 46.5 months while the “C” group with poorer prognostic features (mostly ER- and 2 or more sites) demonstrates a 13.1 month median OS (p < 0.001).

Future directions

Several trials (Table 2) are ongoing to further examine the molecular, immunologic, and clinical characteristics which are associated with long-term non-progression in breast cancer (and other tumor types). It is expected that in the future, larger and prospectively designed clinical trials will include provisions for long-term follow-up of unusual responders along with in-depth analysis of the rising numbers of long-term responders in breast cancer.

Conclusion

Much is still unknown about why certain patients are likely to benefit exceptionally from standard breast cancer treatment. For example, some patients who experience a recurrence after tumor resection can still achieve long-term survival with multi-disciplinary treatment, even in the presence of extensive metastases in multiple organs [44]. Despite the persisting uncertainties, there are several characteristics associated with long-term disease-free survival that can aid in identifying MBC patients who could be treated with curative intent. Our single institution retrospective case series supports existing conclusions about clinical and pathologic characteristics favoring exceptional response. This series suggests that young age, low Charlson comorbidity scores, oligometastatic recurrence and long interval between primary and metastatic recurrence may be associated with long-term non-progression. Not surprisingly, HER2 amplified patients are disproportionately highly represented in the long-term non-progressor group. Weaknesses of this single institutional study include the small sample size, the lack of prospective design and the lack of formal biomarker studies. Future investigations into precise molecular and immunologic markers for exceptional response and perhaps national databases for long-term non-progresssion would be warranted.

Data availability

De-identified primary data stored at UVA data repository and available upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable

References

Spano D, Heck C, De Antonellis P, Christofori G, Zollo M. Molecular networks that regulate cancer metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22(3):234–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.03.006.

Nishikawa G, Luo J, Prasad V. A comprehensive review of exceptional responders to anticancer drugs in the biomedical literature. Eur J Cancer. 2018;101:143–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.06.010.

Harano K, Lei X, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Clinicopathological and surgical factors associated with long-term survival in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159(2):367–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3933-6.

Pagani O, Senkus E, Wood W, et al. International guidelines for management of metastatic breast cancer: can metastatic breast cancer be cured? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(7):456–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq029.

Hattori M, Iwata H. Advances in treatment and care in metastatic breast cancer (MBC): are there MBC patients who are curable? Chin Clin Oncol. 2018;7(3):2. https://doi.org/10.21037/cco.v0i0.19633.

Kalinowski L, Saunus JM, McCart Reed AE, Lakhani SR. Breast Cancer Heterogeneity in Primary and Metastatic Disease. In: Ahmad A, editor. Breast Cancer Metastasis and Drug Resistance: Challenges and Progress. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology: Springer International Publishing; 2019;1152:75–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20301-6_6.

Greenberg PA, Hortobagyi GN, Smith TL, Ziegler LD, Frye DK, Buzdar AU. Long-term follow-up of patients with complete remission following combination chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. Published online September 21, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1996.14.8.2197.

Sledge GW. Curing Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(1):6–10. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2015.008953.

Cheng YC, Ueno NT. Improvement of survival and prospect of cure in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2012;19(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-011-0276-3.

Murthy P, Kidwell KM, Schott AF, et al. Clinical predictors of long-term survival in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;155(3):589–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3705-3.

Dawood S, Broglio K, Ensor J, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Survival differences among women with de novo stage IV and relapsed breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(11):2169–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq220.

Tsimberidou A-M, Hong DS, Wheler JJ, et al. Long-term overall survival and prognostic score predicting survival: the IMPACT study in precision medicine. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-019-0835-1.

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review. Published online 2017. 1975. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/. Accessed 15 March 2021.

Chen M-T, Sun H-F, Zhao Y, et al. Comparison of patterns and prognosis among distant metastatic breast cancer patients by age groups: a SEER population-based analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10166-8.

Tomiak E, Piccart M, Mignolet F, et al. Characterisation of complete responders to combination chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer: a retrospective EORTC breast group study. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32(11):1876–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-8049(96)00189-X.

Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235(4785):177–82. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3798106.

Larionov AA. Current Therapies for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2018;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00089.

Bishop AJ, Ensor J, Moulder SL, et al. Prognosis for patients with metastatic breast cancer who achieve ‘no-evidence-of-disease’ status after systemic or local therapy. Cancer. 2015;121(24):4324–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29681.

Norton N, Fox N, McCarl C-A, et al. Generation of HER2-specific antibody immunity during trastuzumab adjuvant therapy associates with reduced relapse in resected HER2 breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-018-0989-8.

Vaz-Luis I, Seah D, Olson EM, et al. Clinicopathological features among patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor–2-positive breast cancer with prolonged clinical benefit to first-line trastuzumab-based therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2013;13(4):254–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2013.02.010.

Korhonen T, Kuukasjärvi T, Huhtala H, et al. The impact of lobular and ductal breast cancer histology on the metastatic behavior and long term survival of breast cancer patients. Breast. 2013;22(6):1119–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2013.06.001.

Fortunato L, Mascaro A, Poccia I, et al. Lobular breast cancer: same survival and local control compared with ductal cancer, but should both be treated the same way? Analysis of an institutional database over a 10-year period. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(4):1107–14. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-1907-9.

Dian D, Herold H, Mylonas I, et al. Survival analysis between patients with invasive ductal and invasive lobular breast cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(1):23–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-008-0662-z.

Winn JS, Baker MG, Fanous IS, Slack-Davis JK, Atkins KA, Dillon PM. Lobular Breast cancer and abdominal metastases: a retrospective review and impact on survival. Oncology. 2016;91(3):135–42. https://doi.org/10.1159/000447264.

Harris M, Howell A, Chrissohou M, Swindell RI, Hudson M, Sellwood RA. A comparison of the metastatic pattern of infiltrating lobular carcinoma and infiltrating duct carcinoma of the breast. Br J Cancer. 1984;50(1):23–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1984.135.

Chen Z, Yang J, Li S, et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: a special histological type compared with invasive ductal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2017;12(9). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182397.

Narbe U, Bendahl P-O, Aaltonen K, et al. The Distribution of circulating tumor cells is different in metastatic lobular compared to ductal carcinoma of the breast—long-term prognostic significance. Cells. 2020;9(7):1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9071718.

Porter GJR, Evans AJ, Pinder SE, et al. Patterns of metastatic breast carcinoma: influence of tumour histological grade. Clin Radiol. 2004;59(12):1094–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2004.05.001.

Ivshina AV, George J, Senko O, et al. Genetic reclassification of histologic grade delineates new clinical subtypes of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(21):10292–301. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4414.

Li YD, Veliceasa D, Lamano JB, et al. Systemic and local immunosuppression in patients with High-grade meningiomas. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68(6):999–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-019-02342-8.

Wong Y, Raghavendra AS, Hatzis C, et al. Long-term survival of de novo stage IV Human Epidermal Growth Receptor 2 (HER2) Positive breast cancers treated with HER2-targeted therapy. Oncologist. 2019;24(3):313–8. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0213.

Nicolini A, Ferrari P, Duffy MJ. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in breast cancer: Past, present and future. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;52:56–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.08.010.

Hunter N, Croessmann S, Cravero K, Shinn D, Hurley PJ, Park BH. Undetectable tumor cell-free DNA in a patient with metastatic breast cancer with complete response and long-term remission. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2020;18(4):375–9. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2019.7381.

Selzner M, Morse MA, Vredenburgh JJ, Meyers WC, Clavien P-A. Liver metastases from breast cancer: long-term survival after curative resection. Surgery. 2000;127(4):383–9. https://doi.org/10.1067/msy.2000.103883.

Pocard M, Pouillart P, Asselain B, Salmon R-J. Hepatic resection in metastatic breast cancer: results and prognostic factors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26(2):155–9. https://doi.org/10.1053/ejso.1999.0761.

Friedel G, Pastorino U, Ginsberg RJ, et al. Results of lung metastasectomy from breast cancer: prognostic criteria on the basis of 467 cases of the international registry of lung metastases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22(3):335–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1010-7940(02)00331-7.

Andersson Y, Frisell J, Sylvan M, de Boniface J, Bergkvist L. Breast cancer survival in relation to the metastatic tumor burden in axillary lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(17):2868–73. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.24.5001.

Swenerton KD, Legha SS, Smith T, et al. Prognostic factors in metastatic breast cancer treated with combination chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1979;39(5):1552–62.

Kwapisz D. Oligometastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2019;26(2):138–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-018-0921-1.

Kobayashi T, Ichiba T, Sakuyama T, et al. Possible clinical cure of metastatic breast cancer: lessons from our 30-year experience with oligometastatic breast cancer patients and literature review. Breast Cancer. 2012;19(3):218–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-012-0347-0.

Rastogi S, Gulia S, Bajpai J, Ghosh J, Gupta S. Oligometastatic breast cancer: a mini review. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2014;35(3):203–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-5851.142035.

Briasoulis E, Karavasilis V, Kostadima L, Ignatiadis M, Fountzilas G, Pavlidis N. Metastatic breast carcinoma confined to bone. Cancer. 2004;101(7):1524–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20545.

Plichta JKM, Thomas SMM, Sergesketter AR, et al. A novel staging system for de novo metastatic breast cancer refines prognostic estimates. Ann Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004231.

Uramoto H, Hanagiri T. Two cases with a long-term survival following multidisciplinary treatment for recurrent breast cancer after surgery. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(1):277–9.

Funding

University of Virginia Cancer Center Support Grant: 2P30CA044579-26

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Alexander Sytov and Patrick Dillon. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Alexander Sytov and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The retrospective case series was submitted to the University of Virginia Institutional review board on 9/5/2020 and granted exemption status on 9/17/2020. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Waiver provided by the UVA IRB on 9/17/2020

Consent to participate

Waiver for non-identified data use attained from UVA IRB 9/17/2020

Consent for publication

No identifying information/images are contained in this report. No patient identifiers. Consent is waived.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sytov, A., Brenin, C., Millard, T. et al. Long-Term Non-progression in Metastatic Breast Cancer Beyond 5 Years: Case Series and Review. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 13, 208–215 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-021-00410-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-021-00410-6