Abstract

Within Isopoda (woodlice and relatives), there are lineages characterised by a parasitic lifestyle that all belong to Cymothoida and likely form a monophyletic group. Representatives of Epicaridea (ingroup of Cymothoida) are parasitic on crustaceans and usually go through three distinct larval stages. The fossil record of Epicaridea is sparse and thus little is known about the palaeoecology and the origin of the complex life cycle of modern epicarideans. We present an assemblage of over 100 epicarideans preserved in a single piece of Late Cretaceous Myanmar amber. All individuals are morphologically similar to cryptoniscium stage larvae. The cryptoniscium stage usually constitutes the third and last larval stage. In modern representatives of Epicaridea, the cryptoniscium larvae are planktic and search for suitable host animals or adult females. These fossil specimens, though similar to some extant species, differ from other fossil epicaridean larvae in many aspects. Thus, a new species (and a new genus), Cryptolacruma nidis, is erected. Several factors can favour the preservation of multiple conspecific animals in a single piece of amber. However, the enormous density of epicarideans in the herein presented amber piece can only be explained by circumstances that result in high local densities of individuals, close to the resin-producing tree.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Isopoda is a diverse group of crustaceans and its representatives today live in a wide variety of habitats (Brandt 1999; Raupach et al. 2004; Schmidt 2008; Poore and Bruce 2012). Isopoda is a group of primarily marine animals, meaning that the direct ancestor of Isopoda was very likely marine and representatives of most ingroups of Isopoda live in marine environments (Poore and Bruce 2012). However, many ingroups of Isopoda have species that live in brackish or fresh water (Brasil-Lima and De Lima Barros 1998; Wilson and Johnson 1999). The group Oniscidea forms an extreme exception to the aquatic lifestyle found in most representatives of Isopoda as oniscideans live on land and some of them even in arid areas (Schmidt 2008).

Isopoda is an ingroup of Peracarida, which is characterised by females that have a brood pouch formed by lamellae on the legs (oostegites) (Ax 2000). Most freshly hatched immatures of Isopoda resemble the adults in many aspects of their morphology and no drastic changes appear to happen during the further development (Boyko and Wolff 2014). Specialised hatchlings are present in two ingroups of Isopoda that are both characterised by a parasitic lifestyle: Gnathiidae and Epicaridea. Here, more drastic changes occur during the post-embryonic development (Boyko and Wolff 2014). Based on various criteria, representatives of these groups have true larva (discussed in Haug 2020).

Epicarideans mostly live in marine and brackish environments (Markham 1986). However, there are some reports on species living in fresh water (Chopra 1923; Shiino 1954). All epicaridean species parasitise other crustaceans (Markham 1986; but see Pascual et al. (2002) for a record on squids). Epicaridea is closely related to Cymothoidae (possibly a sister group relationship); representatives of Cymothoidae parasitise fishes (Wägele 1989; Dreyer and Wägele 2001). Other closely related groups such as Aegidae or Cymothoidae likewise have representatives parasitising fishes; therefore, it is likely that fishes are the ancestral hosts and the change to crustacean hosts evolved in the common ancestor of epicarideans (Dreyer and Wägele 2001).

The post-embryonic development in Epicaridea is characterised by distinct transformations. With only one exception (Miyashita 1940), epicarideans are released from the brood pouch as epicaridium larvae (Boyko and Wolff 2014). Epicaridium larvae are planktic and search for a small-sized intermediate crustacean host of the group Copepoda to which they attach (Boyko and Wolff 2014). Once an epicaridium larva has attached to its host, it will moult into the microniscium stage. The microniscium stage larvae stay on the small-sized host and feed on its haemolymph (Anderson 1975; Uye and Murase 1997). At some point, the larva moults into the cryptoniscium stage, leaves the host and is again planktic (Boyko and Wolff 2014).

Within Epicaridea, there are lineages with strictly protandric development as well as lineages in which the sex develops triggered by the presence or absence of conspecific parasites on the final host (Wägele 1989). Especially in lineages with strictly protandric development, the cryptoniscium stage is not distinctly differentiable on a morphological basis to later stages (males) in some ingroups of Epicaridea (Hosie 2008). Males are generally much smaller than the females (Shimomura et al. 2005). Female epicarideans often lose their bilateral symmetry, due to their position on the left or right side in the body of the host (Williams and An 2009). In some lineages, the female becomes endoparasitic; this can be accompanied by a drastic loss of sclerotisation (e.g. Shiino 1954). Reconstructions of the possible origin of this complex life cycle have been discussed in Schädel et al. (2019).

Until a few years ago, the fossil record of Epicaridea only consisted of trace fossils. Swellings of the branchial chambers of some shrimps, lobsters and crabs—caused by the presence of large female epicarideans—have been recorded, ranging from the Late Jurassic to the Pleistocene (Bell 1863; Markham 1986; Wienberg Rasmussen et al. 2008; Robins et al. 2013; Klompmaker et al. 2014, 2018; Klompmaker and Boxshall 2015; Robins and Klompmaker 2019). One record (material lost) suggests that such swellings were present even earlier in the Early Jurassic (Soergel 1913).

Recently, body fossils of Epicaridea have been reported from two amber deposits. All epicaridean amber inclusions are from cryptoniscium stage larvae or later stages retaining a cryptoniscium-like morphology. Several 20-million-year-old specimens come from Chiapas, Mexico (Early Miocene, Campo La Granja amber; Serrano-Sánchez et al. 2016), about 99-million-year-old specimens come from Vendée, France (Late Cretaceous, Vendean amber, La Garnache outcrop; Néraudeau et al. 2017; Schädel et al. 2019).

Amber has the potential to preserve very fine details of even small animals (Sidorchuk et al. 2016). Although they make only a small fraction of the overall number of inclusions, aquatic animals can get preserved in amber (e.g. Gustafson et al. 2020). There are also records for supposedly marine organisms on (Mao et al. 2018) and in amber (Girard et al. 2008; Saint Martin et al. 2015; Xing et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2019). Experiments in a modern day swamp have demonstrated that it is possible for animals that are submerged in water to get trapped in resin that is also submerged in water (Schmidt and Dilcher 2007; illustrated in Schädel et al. 2019).

Mass occurrences of individuals of the same species in a single piece of amber have been reported for several amber sites and several lineages of Euarthropoda (Arillo 2007). These lineages include web spiders (Araneae; Poinar and Poinar 1994: fig. 73; Weitschat and Wichard 1998: fig. 20h), springtails (Collembola; Robin et al. 2019), plant lice (Sternorrhyncha; Wang et al. 2014; Szwedo and Drohojowska 2016; Hakim et al. 2019), termites (Isoptera; Grimaldi 1996: 85; Wu 1997: fig. 269; Martı́nez-Delclòs et al. 2004: fig. 3D; Wichard and Weitschat 2004: 107; Arillo 2007: fig. 1D; Vršanský et al. 2019), ants (Formicidae; Grimaldi 1996: 92; Martı́nez-Delclòs et al. 2004: fig. 3C; Arillo 2007: fig. 1C), beetles (Coleoptera; Poinar 1999; Martı́nez-Delclòs et al. 2004: fig. 3E) and flies (Diptera; Brown and Pike 1990; Grimaldi 1996: 84; Ross 1998: fig. 1).

Here, we present an amber piece with more than 100 specimens with a cryptoniscium-like morphology. We describe the fossils and discuss their relationships as well as the unusually high density of inclusions in a single amber piece.

Materials and methods

The amber piece (Myanmar amber, Kachin amber, ‘Burmese’ amber) was acquired from a private collection. Further information on the provenance, including the date of the excavation and export permits are not available. The amber piece is currently part of the PED research collection (Zoomorphology working group, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany). For a discussion on the ethical aspects of the trade of amber fossils, see Haug et al. (2020). The surface of the amber piece was polished using common metal polish (POLIBOY Brandt and Walther GmbH) applied by hand using a sponge.

Microscopic images were made using a Keyence VHX-6000 digital microscope. Overview images of the entire amber piece were recorded under transmitted light combined with cross-polarised coaxial epi-illumination. Detail images of individual specimens were recorded under transmitted light combined with ring-light epi-illumination. The depth-of-field limitations were overcome by recording stacks of images and fusing these to a single sharp image. To overcome the field-of-view limitations, several adjacent image details were recorded, each with a stack, and then stitched to a large panorama image.

For the detail images, a digital method to reduce the effect of reflections was applied (implemented in the software of the microscope). Images from slightly different angles were recorded to produce stereo images. Epi-fluorescence microscopic images were recorded using a Keyence BZ-9000 digital microscope (exciting light of 545 nm wavelength, dichroitic mirror with a wave length of 565 nm, optimised for TRITC stains; Haug et al. 2011a, b; Schädel et al. 2019). The potential of this method was limited by the accessibility of the specimens in the amber piece, as the distance of the specimens to the amber surface was too large. Stacks of images with a different level of the focal plane were recorded and fused using the software CombineZP (GPL licence) (cf. C. Haug et al. 2011a, b).

GIMP (GPL license) was used to optimise image properties (histogram optimisation, brightness, colour and contrast enhancement), to remove backgrounds, to colour-code morphological structures and to create red-cyan stereo anaglyphs.

A Zeiss Xradia XCT-200 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) was used for micro-computed-tomography (µCT) of the amber piece. The Xradia XCT-200 is equipped with switchable scintillator-objective lens units. Tomographies were performed using 0.39 ×, 4 × and 10 × objectives, with the following X-ray source settings: 30 kV, 6 W, 3.5 s exposure time (0.39 × and 4 ×), and 40 kV, 8 W, 4 s exposure time (10×).

Stacks of images (TIF format) were reconstructed based on projections using the XMReconstructor software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). Image stack properties were: (1) overview scan (0.39 ×): system based calculated pixel size = 18 µm, 1024 by 1024 px; (2) 4 × scan: system-based calculated pixel size = 3.16 µm, 1024 by 1024 px; (3) 10 × scan: system-based calculated pixel size = 1.5 µm, 1005 by 1005 px. All scans were performed using ‘Binning 2’ and subsequently reconstructed using ‘Binning 1’ (full resolution).

To exclude further enclosed particles and debris in the final volume, the specimens in the focus of the 10 × scan were roughly “segmented” using TrakEM2 (part of FIJI, GPL license; cf. Kypke and Solodovnikov 2018). Volume rendering was performed in Drishti 2.6.5 (on Linux, using WINE, GPL license; Limaye 2012). The three-dimensional of the specimens within the amber piece was visualised by placing points in Drishti.

The total number of specimens was counted by matching the light microscopic overview images from both sides of the amber piece to the µCT data. Data on the body lengths in Epicaridea was reused from Schädel et al. (2019). All plots were created using R (GPL license) and the packages readr, ggplot2 and gridExtra. The geological scale was added to the plot using the package deeptime (William Gearty, GPL license, https://github.com/willgearty/deeptime). A special colour palette (copyright Paul Tol, https://personal.sron.nl/~pault/) was used to map multiple groups in a single plot, whilst ensuring perceptibility for colour vision impaired readers.

The figure plates were arranged using Inkscape (GPL license). All figure plates were checked for the perceptibility by colour vision impaired readers using the software Color Oracle 1.3 (CC-BY license, Bernhard jenny and Nathaniel V. Kelso).

Taxonomic and systematic information for literature specimens (Supplementary data tables 1–2) was retrieved from the Word Register of Marine Species (“WoRMS”, Boyko et al. 2008 onwards). Large parts of Supplementary data tables 1–2 are reused from Schädel et al. (2019).

Institutional abbreviations. PED, research collection of the Palaeo-Evo-Devo Research Group, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany.

Results

Description of the amber piece

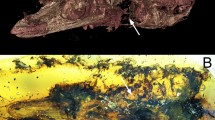

The amber piece is flat on two opposing sides and roughly oval in outline when viewed from either of the flat sides. The amber matrix contains a substantial amount of macroscopic gas-filled bubbles. The amber matrix contains few organic debris particles. Roughly, parallel to the flat sides of the amber piece is a plane within the resin that is less transparent than the surrounding resin. There are 103 small fossils of Euarthropoda (described in detail below) distributed along this plane within the amber matrix (Figs. 1b, 2f). Other organic inclusions are stellate plant trichomes and a single mite.

a, b Holotype of Cryptolacruma nidis gen. et sp. nov., PED 0226-4, µCT-reconstruction, orthographic projection. a Dorsal view. b Ventral view. c Paratype of Cryptolacruma nidis gen. et sp. nov., PED 0226-5, µCT-reconstruction, latero-ventral view, orthographic projection. d, e Holotype of Cryptolacruma nidis gen. et sp. nov., PED 0226-4, detail of the anterior body region, ventral view, light microscopic image. e With colour markings. f µCT-reconstruction of the amber piece, yellow dots depict the position of the fossil isopodans. g Paratype of Cryptolacruma nidis gen. et sp. nov., PED 0226-84, dorsal view, epifluorescence microscopic image. h Holotype of Cryptolacruma nidis gen. et sp. nov., PED 0226-4, detail of the anterior body region, ventral view, red-cyan stereo anaglyphs based on light microscopic image. ant antenna; atl antennula; fl1–5 flagellum elements 1–5 of the antenna; hs head shield; pl1–5 pleon segments 1–5; pr1–7 trunk segments 1–7; pt pleotelson; ub uropod basipod; uen uropod endopod; uex uropod exopod

Description of the specimens

General body shape strictly bilateral, body with multiple segments: presumably 1 ocular segment and 19 post-ocular segments (PO in the following). Body much longer than wide. Outline of body in dorsal view elongated tear-drop shaped, tapering towards posterior end. Dorsal surface convex. Ventral side of body concave (if appendages not considered). Overall body size (without appendages) ranging from 0.45 to 1.29 mm, with mean of 0.83 mm and standard deviation of 0.19 mm (Fig. 3a–a).

a Body lengths of cryptoniscia and paedomorphic males in Epicaridea over time, empty circles depict records for which no affinity to an ingroup of Epicaridea could be identified. b Histogram of measurements of this study (Cryptolacruma nidis gen. et sp. nov., PED 0226). c Ranked size plot, values sorted in ascending order. Simple measurements from microscopy (‘2D’) vs. measurements based on volumetric data from the µCT (‘3D’)

Body organised into functional head (ocular segment and PO 1–6, ‘cephalothorax’) and trunk (PO 7–19 and telson). Trunk divided into three functional units (tagmata): posterior part of thorax (with walking or grasping appendages, PO 7–13, ‘pereon’), anterior part of pleon (with swimming appendages, PO 14–18), and pleotelson (PO 19 and telson). Head segments form single dorsal sclerite (head shield) (Fig. 2a). Each trunk segment with individual dorsal sclerite (tergite). Tergite of trunk segment 1 similar in height and width to posterior margin of head shield (without neck) (Fig. 2a–c). Tergite of last trunk segment continuous with telson. Pleotelson pointed, half-oval shape in dorsal view, posterior margin smooth, without teeth. Striation pattern (shallow, fine-scaled grooves) at least on surface of tergites of trunk segments 3–5.

Antennula (appendage of PO 1) with proximal element large and flat (‘antennular plate’), roughly triangular in ventral view, posterior margin with 4 large teeth. Further distal elements not visible (too small for resolution of µCT with 10 × objective and not accessible by microscopy).

Antenna (appendage of PO 2) subdivided into peduncle (proximal elements) and flagellum (distal elements). 4 peduncle elements visible (likely 5 peduncle elements present, two most proximal elements likely not differentiable in µCT data). Two strong setae on ventral side of distal-most peduncle element (Fig. 2d–e, h). Flagellum much narrower than peduncle, with 5 elements.

Mouthparts not directed in anterior direction and not located between antennular plates; details of individual mouthparts (labrum, appendages of PO 3–6 and paragnaths) not visible.

Anterior trunk appendages (appendages of PO 7–13, ‘pereopods’) not visible, individual elements not discernible in µCT data, only most distal elements accessible in microscopic images. A subdivision into seven elements along the main axis (coxa, basipod, ischium, merus, carpus, propodus and dactylus) is assumed.

Coxa in trunk appendages 2–7 forming scale-like structure (‘coxal plates’) adjoining lateral sides of the tergites. Coxal plates with antero-ventral corner rounded, ventral margin straight, postero-ventral corner rounded, posterior margin straight, posterior margin without teeth, posterior margin with slight serration.

Basipod long and slender in all legs, where visible (trunk appendages 2–7). Further distal elements much shorter. Penultimate element (propodus) compressed in anterior–posterior direction, median margin straight, lateral margin convex. Propodus on trunk appendages 2 and 3 with two strong setae on median side (Fig. 2d–e, 2h). Terminal element (dactylus) much shorter and slenderer than propodus. Dactylus in trunk appendages 1 and 2 curved inwards, more straight in trunk appendages 3 and 4.

Anterior five pleopods (appendages of PO 14–18) subdivided into three elements, all elements strongly compressed in anterior–posterior direction (leaf shaped). Proximal element (basipod) broad, distinctly longer on lateral side, distal margin with distinct angle. Endopod inserting on medio-distal margin of basipod; broad, approximately 0.75 times width of basipod in proximal part; tapering towards distal margin, multiple long setae at distal margin. Exopod inserting on latero-distal margin of basipod; distinctly narrower than endopod, approximately 0.3 times width of basipod; multiple long setae at distal margin. Size of pleopods slightly decreasing from anterior to posterior.

Uropod (appendage of PO 19) subdivided into three elements. Proximal element (basipod) longer than wide, rectangular in posterior view, compressed in anterior–posterior direction (functional dorsal–ventral direction). Endopod inserting on medio-distal margin of basipod; narrow, straight, approximately half of width of basipod, approximately as long as basipod; long setae on distal margin. Exopod inserting on latero-distal margin of basipod; narrow, straight, approximately half of width of basipod, approximately as long as basipod, as long as endopod; long setae on distal margin.

Discussion

Conspecificity of the specimens

The herein presented specimens vary considerably in size (see below); however, the overall morphology is very similar throughout all specimens. We could not find any morphological differences between the specimens that cannot be explained by the size differences of the individuals or the quality of preservation. Thus, it seems likely that all specimens within this amber piece are conspecific.

Systematic affinity of the specimens

The specimens have an ocular segment followed by presumably 19 appendage-bearing body segments; the trunk has a distinct posterior tagma with six segments that appear specialised for swimming (or ventilation). This condition is identifiable as a derived condition of a tagmatisation of the body into a 6–8–6 pattern, i.e. three tagmata: head, thorax, and pleon (the latter with six appendage-bearing segments). This is apomorphic for the eucrustacean ingroup Eumalacostraca (Walossek 1999). The presence of uropods (specialised last trunk appendages) in the herein presented specimens is likewise apomorphic for the group Eumalacostraca (Walossek and Müller 1998). For Isopoda, there is no single, unambiguous apomorphy that is visible in the herein presented fossils; however, the combination of the following character states is indicative for Isopoda: (1) body dorsoventrally flattened; (2) anterior trunk appendages without exopods (Ax 2000; Wilson 2009). The presence of fixed, scale-like coxae (‘coxal plates’) on trunk segments 2–7 is apomorphic for Scutocoxifera, an ingroup of Isopoda (Dreyer and Wägele 2002). Within this group, the combination of the following features is characteristic for cryptoniscium stage larvae of Epicaridea: (1) body tear-drop shaped, tapering posteriorly; (2) anterior trunk appendages with large, sometimes flattened, propodi and (3) with long, spine-like, pointed dactyli; (4) distal (ancestrally movable) claws firmly conjoined with the main part of the dactylus; (5) uropod endo- and exopod rod-shaped (Wägele 1989; Serrano-Sánchez et al. 2016). The proximal element of the antennula is enlarged and with distinct teeth on the posterior margin. This feature is only known from a small number of species within Epicaridea (Schädel et al. 2019).

Exact ontogenetic stage

The morphology of the herein presented specimens is typical for cryptoniscium stage larvae of Epicaridea. This morphology can easily be differentiated from the morphology in earlier larval stages of Epicaridea. Epicaridium larvae are much less elongated, the trunk appendage 7 is absent and the pleopods are located on the lateral margins of the animal (Dale and Anderson 1982; Boyko and Wolff 2014). In microniscium stage larvae of Epicaridea, the appendages of the trunk appear less differentiated; for example, the individual elements of the antenna are not differentiable (Anderson and Dale 1981).

Especially in lineages of Epicaridea in which the representatives show a strictly protandric development, juvenile males can retain the morphology of the cryptoniscium stage (paedomorphosis; Hosie 2008). In other lineages, where the sex is determined by the presence or absence of a female on the final host, the cryptoniscium-like morphology can be lost rapidly in both sexes (Williams and An 2009). Therefore, the exact developmental stage cannot be determined for the herein presented fossils. The fossil specimens in the centre of this study are either cryptoniscium stage larvae or paedomorphic males.

Size variation

We performed two measurement series: (1) based on scaled microscopic images (‘2D’; Fig. 1); (2) based on the overview µCT data (‘3D’; Supplementary image data 1). Not all specimens were measured in both series; some were only visible in the microscopic images, others only in the µCT-based images. The distributions of size classes were similar in both series (Fig. 3b–c). The ‘3D’ measurements generally showed higher values than the ‘2D’ measurements, due to the loss of depth information in the 2D projections. The ‘2D’ measurements are still included, as the number of measured specimens is much higher in this series because many specimens had a weak x-ray contrast (see Supplementary data table 1).

The specimens in the herein presented amber piece vary in their body length. The smallest specimen measures only 0.45 mm, the largest measures 1.29 mm. This variation could indicate the presence of more than one stage within the sample. However, the frequencies of size classes (Fig. 3b–c) do not support this hypothesis, as there are also many specimens with a medium body length present. Whilst it is still possible that the fossils at hand are different instars (e.g. cryptoniscium stage larvae together with paedomorphic later stages), this is not apparent from the observed size distribution.

A large size variation within one stage has previously been reported for cryptoniscium stages. Representatives of Cryptoniscus laevis with a cryptoniscium size range from 0.8 to 2.8 mm (Schultz 1977) constitutes an even wider range than in the herein presented specimens (further ranges can be retrieved from Supplementary data table 1). A contributing factor to wide size ranges in cryptoniscium larvae and males could be the gain in body size during the microniscium stage, up to 300% gain in body length (Anderson 1975; Dale and Anderson 1982), leaving more room for size variation within one life stage than in other ingroups of Euarthropoda (cf. ‘Dyar’s law’/‘Brook’s law’; Dyar 1890; Fowler 1904).

Systematic affinity within Epicaridea

Within Epicaridea, the two groups Cryptoniscoidea (comprising Cabiropidae, Crinoniscidae, Cryptoniscidae, Cyproniscidae, Dajidae, Entophilidae and Hemioniscidae) and Bopyroidea (comprising Bopyridae, Ionidae and Entoniscidae) form a sister group relationship (Boyko et al. 2013; Boyko and Williams 2015). We were not able to determine whether the herein presented specimens belong to either of these two groups, as the characters that we observed did not provide conclusive information (see Supplementary data table 2).

It has been suggested (Boyko et al. 2013; Boyko and Williams 2015) that there is a connection between certain ingroups of Epicaridea and the number of flagellum elements of the antenna. Our literature review (Schädel et al. 2019; Supplementary data table 2) supports that in Cryptoniscoidea the number of antennal flagellum elements is 5, except for Ancyroniscus bonnieri (Holdich 1975, 4 flagellum segments). In Bopyroidea, the number of flagellum elements varies. In representatives of the Bopyroidea ingroup Bopyridae the number of flagellum elements is either 4 or 5, whereas in the supposed sister group Entoniscidae (Boyko et al. 2013) the number of flagellum elements is 3 or less. The low number of flagellum elements in Entoniscidae (Boyko et al. 2013; Boyko and Williams 2015) could be an autapomorphy of the group making an ingroup position of the here presented fossils, which have 5 antennal flagellum elements, very unlikely. Due to the variability in the number of antennal flagellum elements in the other lineages, this character is not informative for the systematic affinity of the here presented fossils.

Comparably a position within Dajidae is very unlikely, because one apomorphy of Dajidae are the specialised mouthparts in the cryptoniscium stage larvae, which form a sucking disc. Although the individual mouthparts are not differentiable in the µCT data or the microscopic images of the here reported fossils, the sucking disc in representatives of Dajidae is so conspicuous that it would be expected to be clearly visible in the microscopic images (e.g. Fig. 2d–e, h). The sucking discs in representatives of Dajidae can easily detach from the rest of the body (Taberly 1954), which, however, does not explain the absence in the here presented fossil specimens, given the high number of studied individuals. The herein presented specimens can, therefore, be interpreted as representatives of Epicaridea, that are not representatives of the ingroups Entoniscidae and Dajidae, hence ‘Epicaridea nec Entoniscidae, nec Dajidae’ (cf. Schädel et al. 2019).

Differential diagnosis

The herein presented specimens differ from the Late Cretaceous amber inclusions of Vacuotheca dupeorum Schädel, Perrichot and Haug, 2019 in having a pleotelson without teeth (with teeth in V. dupeorum). Vacuotheca dupeorum also has distinct teeth on the posterior margin of the coxal plates (Schädel et al. 2019: fig. 14), whereas the herein presented specimens have coxal plates with only slightly serrated posterior margins (Fig. 2b–e). The head shield in the herein presented specimens is flat, whereas in V. dupeorum the head shield is much higher in dorsoventral aspect (Schädel et al. 2019: figs. 5.3–5.5).

The herein presented specimens differ from the Early Miocene fossils from Campo La Granja amber (Chiapas, Mexico) in having uropod endo- and exopods that are of the same length. In the Mexican specimens, either the endopod or the exopod is distinctly longer than its corresponding other distal part of the uropod (Serrano-Sánchez et al. 2016), suggesting that they are likely representatives of at least two distinct species.

Most extant species differ in the combination of the following character states present in the herein presented fossils: (1) antenna with five flagellum elements; (2) uropod with endopod longer than exopod or equal to exopod; (3) antennula with proximal element enlarged in posterior direction (antennular plate); (4) antennular plate with distinct teeth on the posterior margin; (5) posterior margin of the pleotelson without distinct teeth.

There are three species in the literature that also have this combination of characters, but differ in some other aspects. (1) Arcturocheres gaussicola Schultz, 1980 (Cabiropidae) differs from the herein presented specimens in having an uropod exopod that is much shorter than the endopod; also, the pleotelson in A. gaussicola is triangular instead of rounded as in the herein presented specimens (Schultz 1980). (2) Dolichophryxus geminatus Schultz, 1977 (Dajidae) differs from the herein presented specimens in having a much longer antenna (extending up to the anterior end of the pleon); also, specialised mouthparts (sucking discs) as in representatives of Dajidae are not apparent in the herein presented specimens (Schultz 1977). (3) Not formally described specimens from South America (Pascual et al. 2002) differ from the herein presented specimens in having shorter teeth on the posterior margin of the antennular plate and in having a triangular, much more pointed pleotelson (Pascual et al. 2002).

Mass occurrence

In the here described amber piece, more than 100 fossil remains of epicarideans are enclosed, more than three times as many body fossils as known before. This raises the question: how can this mass occurrence be explained? It is unlikely that the embedment happened in a terrestrial environment. Transport by wind or spray can not explain the large number of specimens and the simultaneous low number of other syninclusions.

A passive embedment, e.g. by a resin drop dripping onto the fossilised individuals or overflowing them is also very unlikely. Resin overflowing dead specimens, either on land (e.g. in a dried-out pool) or under water would likely introduce a substantial amount of debris into the resin, which is not present in the here presented amber piece. This is unless there are recurrent resins flows and the specimens lie on a piece of resin. Resin dripping or rapidly flowing into a body of water can probably not cause small aquatic animals, such as cryptoniscium larvae to get in contact with the resin, as the resin would push away the water in which the specimens were located. However, submerged resin can act as an underwater trap in which aquatic arthropods can get stuck, as actuo-palaeontological experiments in a swamp have demonstrated (Schmidt and Dilcher 2007; Schädel et al. 2019: fig. 3).

High abundances of conspecific animals in amber pieces are not uncommon (Arillo 2007). In the following, possible reasons for such assemblages are outlined (visualised in Fig. 4). To have many animals preserved in a piece of resin, the resin piece must act as a trap for a long time or many animals must come in contact with the resin within a short period of time.

Schematic depiction of factors that could have contributed to the taphonomical situation in the herein presented amber piece. Grey boxes, mechanisms that are very unlikely for representatives of Epicaridea. Yellow boxes, mechanisms that are plausible for representatives of Epicaridea. Orange boxes, mechanisms that are likely for representatives of Epicaridea and can explain a high density of individuals. Brown box, mechanism that could in principle explain a high density of Epicaridea individuals, but lacks modern analogues

Entrapment of many conspecific individuals

To have a high number of conspecific animals and a high relative abundance of a single species in the case of a long time trap, representatives of one species must get trapped more frequently than other species. Examples for such an enhanced selective risk of getting trapped are animals that naturally live close to resin, such as ambrosia beetles (Platypodinae; Martı́nez-Delclòs et al. 2004). A species can also be over-represented due to an attraction towards exposed resin. This has been shown for flying stages of insects with aquatic larvae, which are attracted to horizontally polarised light (Horváth et al. 2019). Attraction to polarised light is very unlikely for epicarideans, especially for the herein presented specimens which do not have prominent eyes.

A strong dominance of one species (or the absence of other species) in a specific habitat would promote a high relative abundance in the fossil record. Some amber deposits bear amber pieces with a high content of soil organisms, where springtails often dominate the content in the amber pieces (Robin et al. 2019). It is very unlikely that epicarideans dominate a habitat, as they are parasitic and would thus compete with very few host animals. However, preceding events (see below) could have led to this condition.

A long-term entrapment process is very unlikely for the herein presented amber piece, as all the epicarideans lie in the same plane (Fig. 2f, App. 1–2). This suggests that they probably became trapped on the surface of the resin drop and were then subsequently covered by more resin. In case of a long-term entrapment, the animals should be preserved more randomly throughout the amber piece and potentially even be separated by distinct layers. Such distinct layers of fossil organisms in amber are known from other amber sites with a high content of aquatic organisms (Serrano-Sanchez et al. 2015; Schädel et al. 2019). A stratification of amber in context with aquatic organisms could also be further explained by tidal influence, with the resin being periodically exposed to air and to water (Serrano-Sánchez et al. 2015).

Synchronised hatching or moulting as a factor for high abundance and density

A short-term entrapment with the outcome of a high (relative) abundance of a single species being preserved in the resin requires a temporary high (relative) abundance in proximity to the resin. This high (relative) abundance can either be on a very local scale or on a larger scale.

An example for a larger scale phenomenon would be the synchronised emergence of a specific life stage of this species (e.g. emergence of winged male ants in many colonies: Martı́nez-Delclòs et al. 2004). Such synchronised events could be triggered by biotic factors (e.g. pheromones, abundance of nutrients) or by abiotic factors (e.g. temperature, light, and salinity; Haug et al. 2013).

A synchronised mass moulting from the microniscium stage to the cryptoniscium stage could be triggered for example by a worsening health of an infected population of host animals or the perception of nearby final hosts. This could also explain the enormous size differences in a single life stage. If all microniscia moulted and detached from their intermediate hosts at the same time, some could have parasitised the intermediate host much longer than others. Explaining a high abundance of epicarideans requires a high abundance and density of intermediate hosts (Byron et al. 1983; Ueda et al. 1983; Ambler et al. 1991) as well as a high rate of infestation by epicaridean parasites (but see Uye and Murase 1997; Medeiros et al. 2006). Although plausible, a synchronised moulting event remains speculative, as our knowledge about the ecology of epicarideans is still very limited (Dale and Anderson 1982).

Synchronised events could potentially also play a role on a more local scale. If multiple individuals hatch or emerge at the same time close to a resin source, many of them can get trapped in the same piece of resin. A good example for such a process is a piece of Dominican amber with many small immature spiders (Poinar and Poinar 1999: fig. 73). In Epicaridea, the immatures usually hatch from the brood pouch (marsupium) of the female as epicaridium larvae, which are morphologically very distinct and different to the herein presented specimens. However, there is one species, Entoniscoides okadai Miyashita, 1940, that has been reported to hatch larvae from the brood pouch with a morphology similar to the here presented specimens (Miyashita 1940). The systematic position of this species does not indicate that this type of development is the ancestral condition for Epicaridea (Boyko et al. 2008 onwards). Still, it is not clear exactly when and how the life cycle of most modern epicarideans evolved. This way, despite most observations of the modern fauna do not favour such an explanation, it is possible that simultaneous hatching from a brood pouch may have led to the herein presented taphocoenosis. Yet, the large variation in body sizes seen in the here presented fossil specimens cannot be easily explained by this process, as one would assume that offspring from the same brood pouch should be roughly of the same size (see, e.g. Romero-Rodríguez and Román-Contreras 2008).

Factors explaining high abundance and density of conspecific individuals

There are various other factors which could also lead to a temporary and local high (relative) abundance of a species in proximity to the resin:

-

(1)

Social behaviour: indications of social behaviour can be found in fossils, examples are fossils of worker ants that have been found in Baltic and Dominican amber (Grimaldi 1996, 92; Weitschat and Wichard 1998: fig. 20h; Hörnig et al. 2016). Different types of (sub-) social behaviour have been reported from aquatic and terrestrial representatives of Isopoda (Broly et al. 2012; Salma and Thomson 2016, 2018). In land-living species, such a association could be coupled to the reduction of desiccation by aggregating behaviour (Allee 1926; Broly et al. 2014). In some species of Isopoda, extended parental care has also been reported as a cause for aggregation (Thiel 2003; Tanaka and Nishi 2008). However, social behaviour in epicarideans is rather unlikely due to their parasitic lifestyle that goes along with the competition over attachment sites and limited abundance and physiological capacity of the host animals. In addition, the planktic lifestyle of some of the larval stages (epicaridium and cryptoniscium) renders it unlikely that there is much social behaviour in Epicaridea beyond the maternal care within the brood pouch.

-

(2)

Local abundance of mates: aggregating behaviour for reproductive purposes has been recorded for various ingroups of Isopoda (Holdich 1970; Shuster and Wade 1991; Tanaka and Nishi 2008). In the case of the herein presented taphocoenosis, this could mean that there was an adult female nearby. As females within Epicaridea are immobile and attached to the final host, the search for a mate can coincide with the search for a host.

-

(3)

Local abundance of restricted resources (nutrients, water, minerals, etc.): there are some amber taphocoenoses that indicate an aggregation of beetles around food sources (Poinar 1999; Peris et al. 2020). An aggregating behaviour around food sources can also be seen in different ingroups of Isopoda. Intertidal species of the group Oniscidea have been reported to aggregate in areas with high food content in the sand (Colombini et al. 2005). Giant representatives of Isopoda (Bathynomus A. Milne-Edwards, 1879) aggregate around carcasses on the ocean bottom, on which they feed as scavengers (Lowry and Dempsey 2006). Some non-parasitic representatives of the group Cymothoida are attracted by chemicals released by injured fish on which they prey (Stepien and Brusca 1985). In the case of epicaridean larvae and paedomorphic adults, the two before-mentioned factors can co-occur because mates can be attached to the food source. Within Epicaridea, a larger crustacean (potential host) could be the centre of such an aggregation behaviour. An aggregation of barnacles (Cirripedia), which in modern environments can be parasitised by epicarideans (Nielsen and Strömberg 1973), on the roots of the resin-producing tree could be a plausible explanation why so many cryptoniscium stage individuals are trapped in the amber piece. Fossils of barnacles however, have not been reported from Burmese amber.

-

(4)

Avoidance of predation due to aggregating behaviour: aggregation behaviour is often recognised as an anti-predatory strategy, in which individuals reduce the rate of predatory attacks per individual, compared with a non-aggregation behaviour through the ‘dilution effect’ (Foster and Treherne 1981). This kind of behaviour is known from some species of Peracarida (Thiel 2003, 2011), including Isopoda, but not from epicarideans and thus unlikely to be the reason for the fossil assemblage.

-

(5)

Local shelter from stresses (predation, currents, evaporation, light, etc.): aggregations in areas where there is comparably less biotic (e.g. predation) or abiotic stress (e.g. desiccation) has been reported for different species of Isopoda (Standing and Beatty 1978; Odendaal et al. 1999). In the case presented here the epicarideans could have precautiously avoided predators such as fishes by moving into shallow water areas, where they were closer to the resin-producing trees. Whilst the overall local abundance could increase by this, very high densities are unlikely to be reached and this behaviour has not been reported for epicarideans.

-

(6)

Restriction of the habitat: the restriction of a water body can drastically increase the density of aquatic animals if they survive the chemical stress that often accompanies this process. Results of such processes can be found abundantly in the fossil record (e.g. Wings et al. 2012). Habitat restriction alone is unlikely to have caused the high density of conspecific fossils in the here studied amber piece, because other aquatic organisms would have been affected by this likewise.

A plausible scenario for the formation of the herein studied assemblage of fossil epicarideans has to explain not only a high abundance of individuals, but also a high density of individuals in closest proximity of resin. Most of the above-mentioned factors could have contributed to a high abundance of epicarideans in a habitat on a larger scale. Yet, only few factors can explain a very high density on a small scale. The aggregation due to the presence of a final host may be a plausible explanation for the high abundance of individuals in the amber piece. Yet, it is not clear whether such densities of larval epicarideans regularly occur in modern environments and observations of such in extant species would be interesting find in itself. This all the more emphasises the rarity of such a taphocoenosis preserved in fossilised tree sap. The here studied fossils could also give a hint, that there are aspects of the lifestyle in modern species of Epicaridea which would be worthwhile to investigate further.

Possible host animals in Myanmar amber

The proportion of individuals actually living in water is naturally very low in amber deposits; therefore, there are only few records of animals in Myanmar amber that could potentially have served as final hosts of the herein presented epicarideans. Epicarideans are known to parasitise other species of Isopoda (including other epicarideans; Nielsen and Strömberg 1965; Rybakov 1990). A potential host could thus be an aquatic representative of the group Cymothoida (Schädel et al. 2021 in press). Representatives of the epicaridean ingroup Cyproniscidae are parasitic on seed shrimps (Wägele 1989; Rybakov 1998), which are present in Myanmar amber (Xing et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2020). Modern epicarideans are also parasitic on amphipods (Sars 1899; Wägele 1989) and true crabs (Brachyura) (Torres Jordá 2003), which are also present in Myanmar amber (Zhang 2017).

Taxonomy

This published work and the nomenclatural acts it contains have been registered with Zoobank under the Life Science Identifier (LSID) urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:755965DF-B4A6-4A87-B513-1A6A26B72F5E

Isopoda Latreille, 1817

Scutocoxifera Dreyer and Wägele, 2002

Cymothoida Wägele, 1989

Epicaridea Latreille, 1825 (= Bopyridae Rafinesque, 1815 sensu Wägele 1989)

Cryptolacruma gen. nov.

Etymology. The name is derived from the cryptoniscium stage (a larval stage in Epicaridea) and from the Latin lacruma for ‘resin’ in reference to the occurrence in amber. The gender is feminine. The name also translates to ‘hidden tear’, in memory of the victims of commercial amber mining.

LSID. urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:EBE923E5-E0CB-45B3-89A7-627756EEBE88.

Remark. This genus name is merely created to be compliant with the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Since the name stands for a monotypic (uninformative) taxonomic unit, the diagnosis is the same as for the species.

Cryptolacruma nidis sp. nov.

Figures 1, 2; Supplementary image data 1, 2, 3

Holotype. PED 0226-4.

Paratypes. PED 0226-1–PED 0226-3, PED 0226-5–PED 0226-103. Ontogenetic stage of the type specimens: cryptoniscium type larvae, paedomorphic juveniles or paedomorphic males.

Etymology. The name is derived from the Latin nidus for ‘nest’ (locative case, plural) in reference to the high number of specimens in the amber piece containing the type specimens.

LSID. urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:5E0591E7-00B5-483C-AC8F-D0D195BB2BB3.

Type locality. Near Noje Bum, Hukawng Valley, Kachin State, Myanmar.

Type stratum and age. Unknown stratum, 98.8 million years, lowermost Cenomanian, lowermost Upper Cretaceous (Shi et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2019).

Differential diagnosis. Head shield flat, antennula with proximal element enlarged in posterior direction (‘antennular plate’); antennular plate with distinct teeth on posterior margin; antenna with terminal peduncle element long and slender, five flagellum elements; mouthparts not specialised as a sucking disc; uropod endopod as long as exopod; pleotelson posterior margin rounded, not pointed, without distinct teeth.

Systematic interpretation. Epicaridea nec Dajidae, nec Entoniscidae.

Conclusions

The herein presented piece of Myanmar amber contains more than 100 inclusions of cryptoniscium stage larvae or paedomorphic males of Epicaridea. This represents the oldest record of body fossils of the group Epicaridea (parasites of crustaceans); it is also one of only three body fossil occurrences of this group and increases the overall number of body fossil of this group by a factor of 4. The morphology of the specimens is comparable to that of extant species; however, the combination of character states is unique. The accumulation of this many specimens in a single piece of resin is a remarkable example for mass occurrences of conspecific organisms in amber.

Data availability

All supplementary files are available via MorphDBase.

Supplementary image data 1: µCT data of PED 0226, 0.39x objective, 30 kV, 6 W, 3.5 s exposure time. TIF format, system based calculated pixel size = 18 µm. Available from https://www.morphdbase.de/?M_Schaedel_20200612-M-31.1

Supplementary image data 2: µCT data of PED 0226, 4x objective, 30 kV, 6 W, 3.5 s exposure time. TIF format, system based calculated pixel size = 3.16 µm. Available from https://www.morphdbase.de/?M_Schaedel_20200612-M-33.1

Supplementary image data 3: µCT data of PED 0226, 10x objective, 40 kV, 8 W, 4 s exposure time. TIF format, system based calculated pixel size = 1.5 µm. Available from https://www.morphdbase.de/?M_Schaedel_20200612-M-32.1

Supplementary data table 1: Body lengths of cryptoniscium stage representatives of Epicaridea, data for Fig. 3, csv-format (comma as separator, UTF-8 character encoding) (Fraisse 1878; Bonnier 1900; Thompson 1902; Caullery 1907; Miyashita 1940; Shiino 1954; Nielsen and Strömberg 1965; Bresciani 1966; Bourdon 1967, 1972, 1976a, 1976b, 1980, 1981, 1983, 1980; Nielsen 1967; Strömberg 1971; Holdich 1975; Schultz 1977; Kensley 1979; Bourdon and Bruce 1980; Anderson and Dale 1981; Coyle and Mueller 1981; Dale and Anderson 1982; Adkison and Collard 1990; Rybakov 1990; Shields and Ward 1998; Pascual et al. 2002; Torres Jordá 2003; Shimomura et al. 2005; Hosie 2008; Romero-Rodríguez and Román-Contreras 2013; An et al. 2015; Serrano-Sánchez et al. 2016; Schädel et al. 2019). Available from https://www.morphdbase.de/?M_Schaedel_20200812-M-36.1

Supplementary data table 2: Morphological features of fossil and extant representatives of Epicaridea, csv-format (comma as separator, UTF-8 character encoding) (Fraisse 1878; Giard and Bonnier 1887; Bonnier 1900; Thompson 1902; Caullery 1907; Miyashita 1940; Shiino 1954; Nielsen and Strömberg 1965; Bresciani 1966; Bourdon 1967, 1972, 1976a, 1976b, 1980, 1981, 1980, 2015; Holdich 1975; Schultz 1977; Kensley 1979; Bourdon and Bruce 1980; Anderson and Dale 1981; Coyle and Mueller 1981; Dale and Anderson 1982; Adkison and Collard 1990; Rybakov 1990; Pascual et al. 2002; Torres Jordá 2003; Shimomura et al. 2005; Hosie 2008; Boyko 2013; Serrano-Sánchez et al. 2016; Schädel et al. 2019). Available from https://www.morphdbase.de/?M_Schaedel_20200812-M-35.1

References

Adkison, D.L., and S.B. Collard. 1990. Description of the cryptoniscium larva of Entophilus omnitectus Richardson, 1903 (Crustacea: Isopoda: Epicaridea) and records from the Gulf of Mexico. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 103(3): 649–654.

Allee, W.C. 1926. Studies in animal aggregations: causes and effects of bunching in land isopods. Journal of Experimental Zoology 45(1): 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.1400450108.

Ambler, J.W., F.D. Ferrari, and J.A. Fornshell. 1991. Population structure and swarm formation of the cyclopoid copepod Dioithona oculata near mangrove cays. Journal of Plankton Research 13(6): 1257–1272. https://doi.org/10.1093/plankt/13.6.1257.

An, J., C.B. Boyko, and X. Li. 2015. A review of bopyrids (Crustacea: Isopoda: Bopyridae) parasitic on caridean shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea) from China. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 399: 1–85. https://doi.org/10.1206/amnb-921-00-01.1.

Anderson, G. 1975. Larval metabolism of the epicaridian isopod parasite Probopyrus pandalicola and metabolic effects of P. pandalicola on its copepod intermediate host Acartia tonsa. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 50(4): 747–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/0300-9629(75)90140-1.

Anderson, G., and W. Dale. 1981. Probopyrus pandalicola (Packard) (Isopoda, Epicaridea): morphology and development of larvae in culture. Crustaceana 41(2): 143–161.

Arillo, A. 2007. Paleoethology: fossilized behaviours in amber. Geologica Acta 5(2): 159–166.

Ax, P. 2000. The phylogenetic system of the Metazoa. In Multicellular Animals, ed. S. Kinsey. Berlin: Springer.

Bell, T. 1863. A monograph of the fossil malacostracous Crustacea of Great Britain. Part II, Crustacea of the Gault and Greensand. Monographs of the Palaeontographical Society 14(63): 1–40.

Bonnier, J. 1900. Contribution à l’étude des épicarides les Bopyridae. Travaux de la Station Zoologique de Wimereux 8: 1–476.

Bourdon, R. 1967. Sur quelques nouvelles espèces de Cabiropsidae (Isopoda Epicaridea). Bulletin du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle 38(6): 846–868.

Bourdon, R. 1972. Epicarides de la Galathea expedition. Galathea Report 12: 101–112.

Bourdon, R. 1976a. Épicarides de Madagascar I. Bulletin du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (3e Série) 371(3): 353–392.

Bourdon, R. 1976b. Les Bopyres des Porcellanes. Bulletin du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (3e Série) 359(3): 353–392.

Bourdon, R. 1980. Aporobopyrus dollfusi n. sp. (Crustacea, Epicaridea, Bopyridae) parasite de Porcellanes de la mer Rouge. Bulletin du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (4e Série) 2: 237–244.

Bourdon, R. 1981. Trois nouveaux Cryptoniscina antarctiques abyssaux (Isopoda, Epicaridea). Bulletin du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle 3: 603–613.

Bourdon, R., and N.L. Bruce. 1980. Ancyroniscus orientalis sp. nov. (Isopoda: Epicaridea), nouveau cabiropside parasite de la great barrier reef. Bulletin de l'Academie et de la Societe Lorraines des Sciences 19(1): 21–26.

Boyko, C.B. 2013. Toward a monophyletic Cabiropidae: a review of parasitic isopods with female Cabirops-type morphology (Isopoda: Cryptoniscoidea). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 126: 103–119. https://doi.org/10.2988/0006-324X-126.2.103.

Boyko, C.B. 2015. A revision of Danalia Giard, 1887, Faba Nierstrasz & Brender à Brandis, 1930 and Zeuxokoma Grygier, 1993 (Crustacea: Isopoda: Epicaridea: Cryptoniscoidea: Cryptoniscidae) with description of a new genus and four new species. Bishop Museum Bulletin in Zoology 9: 65–92.

Boyko, C.B., and J.D. Williams. 2015. A new genus for Entophilus mirabiledictu Markham & Dworschak, 2005 (Crustacea: Isopoda: Cryptoniscoidea: Entophilidae) with remarks on morphological support for epicaridean superfamilies based on larval characters. Systematic Parasitology 92(1): 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11230-015-9578-8.

Boyko, C.B., and C. Wolff. 2014. Isopoda and Tanaidacea. In Atlas of crustacean Larvae, eds. J.W. Martin, J. Olesen, and J.T. Hoeg, 210–212. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Boyko, C.B., N.L. Bruce, K.A. Hadfield, K.L. Merrin, Y. Ota, G.C.B. Poore, S. Taiti, M. Schotte, and G.D.F. Wilson 2008 onwards. World Marine, Freshwater and Terrestrial Isopod Crustaceans database. Epicaridea. http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=13795 on 2018–08–07. Accessed 3 October 2020.

Boyko, C.B., J. Moss, J.D. Williams, and J.D. Shields. 2013. A molecular phylogeny of Bopyroidea and Cryptoniscoidea (Crustacea: Isopoda). Systematics and Biodiversity 11(4): 495–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2013.865679.

Brandt, A. 1999. On the origin and evolution of Antarctic Peracarida (Crustacea, Malacostraca). Scientia Marina 63: 261–274. https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.1999.63s1261.

Brasil-Lima, I.M., and C.M. De Lima Barros. 1998. Malacostraca - Peracarida Freshwater Isopoda Flabellifera and Asellota. In Catalogue of Crustacea of Brazil, ed. P.S. Young, 645–651. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional.

Bresciani, J. 1966. Aegophila socialis gen. et. sp. nov., an epicaridean parasitic on the isopod Aega ventrosa Sars. Ophelia 3(1): 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00785326.1966.10409636.

Broly, P., R. Mullier, J. Deneubourg, and C. Devigne. 2012. Aggregation in woodlice: social interaction and density effects. ZooKeys 176: 133–144. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.176.2258.

Broly, P., L. Devigne, J. Deneubourg, and C. Devigne. 2014. Effects of group size on aggregation against desiccation in woodlice (Isopoda: Oniscidea). Physiological Entomology 39(2): 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/phen.12060.

Brown, B.V., and E.M. Pike. 1990. Three new fossil phorid flies (Diptera: Phoridae) from Canadian Late Cretaceous amber. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 27(6): 845–848. https://doi.org/10.1139/e90-087.

Byron, E.R., P.T. Whitman, and C.R. Goldman. 1983. Observations of copepod swarms in Lake Tahoe1. Limnology and Oceanography 28(2): 378–382. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1983.28.2.0378.

Caullery, M. 1907. Recherches sur les Liriopsidae, Épicarides cryptonisciens parasites des Rhizocéphales. Mittheilungen aus der Zoologischen Station zu Neapel 18: 583–643.

Chopra, B. 1923. Bopyrid isopods parasitic on Indian Decapoda Macrura. Records of the Indian Museum 25(2): 411–550.

Colombini, I., M. Fallaci, and L. Chelazzi. 2005. Micro-scale distribution of some arthropods inhabiting a Mediterranean sandy beach in relation to environmental parameters. Acta Oecologica 28(3): 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2005.05.006.

Coyle, K.O., and G.J. Mueller. 1981. Larval and juvenile stages of the isopod Holophryxus alaskensis (Epicarida, Dajidae) parasitic on decapods. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 38(11): 1438–1443. https://doi.org/10.1139/f81-190.

Dale, W.E., and G. Anderson. 1982. Comparison of morphologies of Probopyrus bithynis, P. floridensis, and P. pandalicola larvae reared in culture (Isopoda, Epicaridea). Journal of Crustacean Biology 2(3): 392–409.

Dreyer, H., and J.W. Wägele. 2001. Parasites of crustaceans (Isopoda: Bopyridae) evolved from fish parasites: molecular and morphological evidence. Zoology 103(3/4): 157–178.

Dreyer, H., and J.W. Wägele. 2002. The Scutocoxifera tax. Nov. and the information content of nuclear ssu rDNA sequences for reconstruction of isopod phylogeny (Peracarida: Isopoda). Journal of Crustacean Biology 22(2): 217–234.

Dyar, H.G. 1890. The number of molts of lepidopterous larvae. Psyche A Journal of Entomology 5: 420–422. https://doi.org/10.1155/1890/23871.

Foster, W.A., and J.E. Treherne. 1981. Evidence for the dilution effect in the selfish herd from fish predation on a marine insect. Nature 293: 466–467. https://doi.org/10.1038/293466a0.

Fowler, G.H. 1904. Biscayan plankton collected during a cruise of H.M.S. “Research” 1900. Part xii. The Ostracoda. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 2(10): 219–336.

Fraisse, P. 1878. Die Gattung Cryptoniscus Fr. Müller. Arbeiten aus dem Zoologisch-Zootomischen Institut in Würzburg 4: 239–296.

Giard, A., and J.J. Bonnier. 1887. Contributions à l’étude des Bopyriens. Travaux de la Station Zoologique de Wimereux 5: 1–252.

Girard, V., A.R. Schmidt, S. Saint Martin, S. Struwe, V. Perrichot, J.P. Saint Martin, D. Grosheny, G. Breton, and D. Néraudeau. 2008. Evidence for marine microfossils from amber. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105(45): 17426–17429. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0804980105.

Grimaldi, D.A. 1996. Amber, window to the past. New York: American Museum of Natural History, published by Harry N. Abrams Inc.

Gustafson, G.T., M.C. Michat, and M. Balke. 2020. Burmese amber reveals a new stem lineage of whirligig beetle (Coleoptera: Gyrinidae) based on the larval stage. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 189(4): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz161.

Hakim, M., D. Azar, and D. Huang. 2019. Protopsyllidioids, and their behaviour “frozen” in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. Palaeoentomology 2(3): 271–278. https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.2.3.12.

Haug, J.T. 2020. Why the term “larva” is ambiguous, or what makes a larva? Acta Zoologica 101(2): 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/azo.12283.

Haug, C., G. Mayer, V. Kutschera, D. Waloszek, A. Maas, and J.T. Haug. 2011a. Imaging and documenting gammarideans. International Journal of Zoology 2011: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/380829.

Haug, J.T., C. Haug, V. Kutschera, G. Mayer, A. Maas, S. Liebau, C. Castellani, U. Wolfram, E.N.K. Clarkson, and D. Waloszek. 2011b. Autofluorescence imaging, an excellent tool for comparative morphology. Journal of Microscopy 244(3): 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2818.2011.03534.x.

Haug, J.T., J.B. Caron, and C. Haug. 2013. Demecology in the Cambrian: synchronized molting in arthropods from the Burgess Shale. BMC Biology 11(1): 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-11-64.

Haug, C., J.W.F. Reumer, J.T. Haug, A. Arillo, D. Audo, D. Azar, V. Baranov, R. Beutel, S. Charbonnier, R. Feldmann, C. Foth, R.H.B. Fraaije, P. Frenzel, R. Gašparič, D.E. Greenwalt, D. Harms, M. Hyžný, J.W.M. Jagt, E.A. Jagt-Yazykova, E. Jarzembowski, H. Kerp, A.G. Kirejtshuk, C. Klug, D.S. Kopylov, U. Kotthoff, J. Kriwet, L. Kunzmann, R.C. McKellar, A. Nel, C. Neumann, A. Nützel, V. Perrichot, A. Pint, O. Rauhut, J.W. Schneider, F.R. Schram, G. Schweigert, P. Selden, J. Szwedo, B.W.M. van Bakel, T. van Eldijk, F.J. Vega, B. Wang, Y. Wang, L. Xing, and M. Reich. 2020. Comment on the letter of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) dated April 21, 2020 regarding “Fossils from conflict zones and reproducibility of fossil-based scientific data”: the importance of private collections. PalZ. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 94: 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12542-020-00522-x.

Holdich, D.M. 1970. The distribution and habitat preferences of the Afro-European species of Dynamene (Crustacea: Isopoda). Journal of Natural History 4(3): 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222937000770401.

Holdich, D.M. 1975. Ancyroniscus bonnieri (Isopoda, Epicaridea) infecting British populations of Dynamene bidentata (Isopoda, Sphaeromatidae). Crustaceana 28(2): 145–151.

Hörnig, M.K., A. Sombke, C. Haug, S. Harzsch, and J.T. Haug. 2016. What nymphal morphology can tell us about parental investment: a group of cockroach hatchlings in Baltic Amber documented by a multi-method approach. Palaeontologia Electronica 19.1.6A: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.26879/571.

Horváth, G., A. Egri, V.B. Meyer-Rochow, and G. Kriska. 2019. How did amber get its aquatic insects? Water-seeking polarotactic insects trapped by tree resin. Historical Biology 33: 846–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2019.1663843.

Hosie, A.M. 2008. Four new species and a new record of Cryptoniscoidea (Crustacea: Isopoda: Hemioniscidae and Crinoniscidae) parasitising stalked barnacles from New Zealand. Zootaxa 1795: 1–28.

Kensley, B. 1979. Redescription of Zonophryxus trilobus Richardson, with notes on the male and developmental stages (Crustacea: Isopoda: Dajidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 92(3): 665–670.

Klompmaker, A.A., and G.A. Boxshall. 2015. Fossil crustaceans as parasites and hosts. Advances in Parasitology 90: 233–289.

Klompmaker, A.A., P. Artal, B.W.M. van Bakel, R.H.B. Fraaije, and J.W.M. Jagt. 2014. Parasites in the fossil record: a Cretaceous fauna with isopod-infested decapod crustaceans, infestation patterns through time, and a new ichnotaxon. PLoS ONE 9(3): 1–17.

Klompmaker, A.A., C.M. Robins, R.W. Portell, and A. De Angeli. 2018. Crustaceans as hosts of parasites throughout the Phanerozoic. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/505495.

Kypke, J.L., and A. Solodovnikov. 2018. Every cloud has a silver lining: X-ray micro-CT reveals Orsunius rove beetle in Rovno amber from a specimen inaccessible to light microscopy. Historical Biology 32: 940–950. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2018.1558222.

Limaye, A. 2012. Drishti: a volume exploration and presentation tool. Proceedings of SPIE the International Society for Optical Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.935640.

Lowry, J., and K. Dempsey. 2006. The giant deep-sea scavenger genus Bathynomus (Crustacea, Isopoda, Cirolanidae) in the Indo-West Pacific. In Tropical deep-sea benthos, vol. 24, eds. B. Richer de Forges and J.L. Justine. Memoires du Museum national d’Histoire naturelle 193: 163–192.

Mao, Y., K. Liang, Y. Su, J. Li, X. Rao, H. Zhang, F. Xia, Y. Fu, C. Cai, and D. Huang. 2018. Various amberground marine animals on Burmese amber with discussions on its age. Palaeoentomology 1(1): 91–103. https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.1.1.11.

Markham, J.C. 1986. Evolution and zoogeography of the Isopoda Bopyridae, parasites of Crustacea Decapoda. In Crustacean Issues 4. Crustacean Biogeography, eds. H.G. Robert and L.H. Kenneth, 143–164. Rotterdam: A.A Balkema.

Martı́nez-Delclòs, X., X. Briggs, and X. Peñalver. 2004. Taphonomy of insects in carbonates and amber. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 203: 19–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(03)00643-6.

Medeiros, G.F., L.S. Medeiros, D.M.F. Henriques, M.T. Lima e Carlos, G.V.F. Benigna de Souza, and R.M. Lopes. 2006. Current distribution of the exotic copepod Pseudodiaptomus trihamatus Wright, 1937 along the northeastern coast of Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Oceanography 54(4): 241–245. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-87592006000300008.

Miyashita, Y. 1940. On an entoniscid with abbreviated development, Entoniscoides okadai, n. g., n. sp. Annotationes Zoologicae Japonenses 19(2): 149–157.

Néraudeau, D., V. Perrichot, D.J. Batten, A. Boura, V. Girard, L. Jeanneau, Y.A. Nohra, F. Polette, S. Saint Martin, and J.P. Saint Martin. 2017. Upper Cretaceous amber from Vendée, north-western France: age dating and geological, chemical, and palaeontological characteristics. Cretaceous Research 70: 77–95.

Nielsen, S.O. 1967. Cironiscus dahli gen. et sp. nov. (Crustacea, Epicaridea) with notes on host-parasite relations and distribution. Sarsia 29(1): 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/00364827.1967.10411096.

Nielsen, S.O., and J.O. Strömberg. 1965. A new parasite of Cirolana borealis Lilljeborg belonging to the Cryptoniscinae (Crustacea Epicaridea). Sarsia 18(1): 37–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00364827.1965.10409547.

Nielsen, S., and J. Strömberg. 1973. Morphological characters of taxonomical importance in Cryptoniscina (Isopoda Epicaridea) A scanning electron microscopic study of Cryptoniscus Larvae. Sarsia 52(1): 75–96.

Odendaal, F.J., S. Eekhout, A.C. Brown, and G.M. Branch. 1999. Aggregations of the sandy-beach isopod, Tylos granulatus: adaptation or incidental-effect? African Zoology 34(4): 180–189.

Pascual, S., M.A. Vega, F.J. Rocha, and A. Guerra. 2002. First report of an endoparasitic epicaridean isopod infecting cephalopods. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 38: 473–477. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-38.2.473.

Peris, D., C.C. Labandeira, E. Barrón, X. Delclòs, J. Rust, and B. Wang. 2020. Generalist pollen-feeding beetles during the mid-Cretaceous. iScience. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.100913.

Poinar, G.O. 1999. Chrysomelids in fossilized resin: behavioural inferences. In Advances in chrysomelidae biology 1, ed. M.L. Cox, 1–16. Leiden: Backhuys Publishers.

Poinar, G.O., and R. Poinar. 1994. The quest for life in amber. Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Poinar, G.O., and R. Poinar. 1999. The amber forest. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Poore, G.C.B., and N.L. Bruce. 2012. Global diversity of marine isopods (except Asellota and crustacean symbionts). PLoS ONE 7(8): e43529. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043529.

Raupach, M.J., C. Held, and J.W. Wägele. 2004. Multiple colonization of the deep sea by the Asellota (Crustacea: Peracarida: Isopoda). Deep Sea Research Part II 51(14–16): 1787–1795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2004.06.035.

Robin, N., C. D’Haese, and P. Barden. 2019. Fossil amber reveals springtails’ longstanding dispersal by social insects. BMC Evolutionary Biology 19: 213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-019-1529-6.

Robins, C.M., and A.A. Klompmaker. 2019. Extreme diversity and parasitism of Late Jurassic squat lobsters (Decapoda: Galatheoidea) and the oldest records of porcellanids and galatheids. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 187(4): 1131–1154. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz067.

Robins, C.M., R.M. Feldmann, and C.E. Schweitzer. 2013. Nine new genera and 24 new species of the Munidopsidae (Decapoda: Anomura: Galatheoidea) from the Jurassic Ernstbrunn Limestone of Austria, and notes on fossil munidopsid classification. Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien (A: Mineralogie und Petrographie, Geologie und Paläontologie, Anthropologie und Prähistorie) 115: 167–251.

Romero-Rodríguez, J., and R. Román-Contreras. 2008. Aspects of the reproduction of Bopyrinella thorii (Richardson, 1904) (Isopoda, Bopyridae), a branchial parasite of Thor floridanus Kingsley, 1878 (Decapoda, Hippolytidae) in Bahía de la Ascensión, Mexican Caribbean. Crustaceana 81(10): 1201–1210. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854008X374522.

Romero-Rodríguez, J., and R. Román-Contreras. 2013. Prevalence and reproduction of Bopyrina abbreviata (Isopoda, Bopyridae) in Laguna de Términos, SW Gulf of Mexico. Journal of Crustacean Biology 33(5): 641–650. https://doi.org/10.1163/1937240X-00002182.

Ross, A. 1998. Amber. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rybakov, A.V. 1990. Bourdonia tridentata gen n., sp. n. (Isopoda: Cabiropsidae) a hyperparasite of Bopyroides hippolytes Kroyer [sic] from the shrimp Pandalus borealis. Parazitologiia 24(5): 408–416.

Rybakov, A.V. 1998. Onisocryptus kurilensis sp. n. (Crustacea, Isopoda, Cyproniscidae), a parasite of the ostracod Vargula norvegica orientalis. Russian Journal of Marine Biology 24(5): 337–339 (in Russian).

Saint Martin, S., J.P. Saint Martin, A.R. Schmidt, V. Girard, D. Néraudeau, and V. Perrichot. 2015. The intriguing marine diatom genus Corethron in Late Cretaceous amber from Vendée (France). Cretaceous Research 52: 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2014.07.006.

Salma, U., and M. Thomson. 2016. Gregarious aggregative behavior in the marine isopod Cirolana harfordi. Invertebrate Biology 135(3): 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/ivb.12134.

Salma, U., and M. Thomson. 2018. Social aggregation of the marine isopod Cirolana harfordi does not rely on the availability of light-reducing shelters. Physiological Entomology 43(1): 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/phen.12229.

Sars, G.O. 1899. An account of the Crustacea of Norway, with short descriptions and figures of all the species. Volume II. Isopoda. Bergen: Bergen Museum.

Schädel, M., V. Perrichot, and J.T. Haug. 2019. Exceptionally preserved cryptoniscium larvae: morphological details of rare isopod crustaceans from French Cretaceous Vendean amber. Palaeontologia Electronica 22.3.71: 1–46. https://doi.org/10.26879/977.

Schädel, M., M. Hyžný, and J.T. Haug. 2021. Ontogenetic development captured in amber: the first record of aquatic representatives of Isopoda in Cretaceous amber from Myanmar. Nauplius 29: e2021003, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1590/2358-2936e2021003.

Schmidt, C. 2008. Phylogeny of the terrestrial Isopoda (Oniscidea): a review. Arthropod Systematics and Phylogeny 66(2): 191–226.

Schmidt, A.R., and D.L. Dilcher. 2007. Aquatic organisms as amber inclusions and examples from a modern swamp forest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(42): 16581–16585. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707949104.

Schultz, G.A. 1977. Bathypelagic isopod Crustacea from the Antarctic and Southern Seas. In Biology of the Antarctic Seas, ed. G.A. Schultz, 69–128. Washington: American Geophysical Union.

Schultz, G.A. 1980. Arcturocheres gaussicola n. sp. (Cabiropsidae) parasite on Antarcturus gaussianus Vanhöffen (Arcturidae) from Antarctica (Isopoda). Crustaceana 39(2): 153–156. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854080X00058.

Serrano-Sánchez, M.L., T.A. Hegna, P. Schaaf, L. Pérez, E. Centeno-García, and F.J. Vega. 2015. The aquatic and semiaquatic biota in Miocene amber from the Campo La Granja mine (Chiapas, Mexico): paleoenvironmental implications. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 62: 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2015.06.007.

Serrano-Sánchez, M.L., C. Nagler, C. Haug, J.T. Haug, E. Centeno-García, and F.J. Vega. 2016. The first fossil record of larval stages of parasitic isopods: cryptoniscus larvae preserved in Miocene amber. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 279(1): 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1127/njgpa/2016/0543.

Shi, G., D.A. Grimaldi, G.E. Harlow, J. Wang, J. Wang, M. Yang, W. Lei, Q. Li, and X. Li. 2012. Age constraint on Burmese amber based on U-Pb dating of zircons. Cretaceous Research 37: 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2012.03.014.

Shields, J.D., and L.A. Ward. 1998. Tiarinion texopallium, new species, an entoniscid isopod infesting majid crabs (Tiarinia spp.) from the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Journal of Crustacean Biology 18(3): 590–596.

Shiino, S.M. 1954. A new fresh-water entoniscid isopod, Entionella okayamaensis n. sp. Report of the Faculty of Fisheries, Prefectural University of Mie 1(3): 239–246.

Shimomura, M., S. Ohtsuka, and K. Naito. 2005. Prodajus curviabdominalis n. sp. (Isopoda: Epicaridea: Dajidae), an ectoparasite of mysids, with notes on morphological changes, behaviour and life-cycle. Systematic Parasitology 60(1): 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11230-004-1375-8.

Shuster, S.M., and M.J. Wade. 1991. Female copying and sexual selection in a marine isopod crustacean Paracerceis sculpta. Animal Behaviour 41(6): 1071–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80645-1.

Sidorchuk, E.A., V. Perrichot, and E.E. Lindquist. 2016. A new fossil mite from French Cretaceous amber (Acari: Heterostigmata: Nasutiacaroidea superfam. nov.), testing evolutionary concepts within the Eleutherengona (Acariformes). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 14(4): 297–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2015.1046512.

Soergel, W. von. 1913. Lias und Dogger von Jefbei und Fialpopo (Misólarchipel). In Geologische Mitteilungen aus dem Indo-Australischen Archipel, ed. G. Boehm. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie etc. 36: 586–650.

Standing, J.D., and D.D. Beatty. 1978. Humidity behaviour and reception in the sphaeromatid isopod Gnorimosphaeroma oregonensis (Dana). Canadian Journal of Zoology 56(9): 2004–2014. https://doi.org/10.1139/z78-270.

Stepien, C.A., and R.C. Brusca. 1985. Nocturnal attacks on nearshore fishes in southern California by crustacean zooplankton. Marine Ecology Progress Series 25(1): 91–105.

Strömberg, J.O. 1971. Contribution to the embryology of bopyrid isopods with special reference to Bopyroides, Hemiarthrus, and Peseudione [sic] (Isopoda, Epicaridea). Sarsia 47(1): 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00364827.1971.10411191.

Strömberg, J.O. 1983. A redescription of Onisocryptus sagittus Schultz 1977 (Epicaridea, Cryptoniscina) with notes on hosts, distribution and family relationships. Polar Biology 2(2): 87–94.

Szwedo, J., and J. Drohojowska. 2016. A swarm of whiteflies—the first record of gregarious behavior from Eocene Baltic amber. The Science of Nature 103(35): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-016-1359-y.

Taberly, G. 1954. Etude morphologique d’un Dajidae peu connu: Prodajus lobiancoi Bonnier (Crust. Isop. Epicaridae) II. —Le cryptoniscium de P. lobiancoi et sa mue formes connues de cryptoniscium de Dajidae. Bulletin d’Institut Océanographique 1049: 1–15.

Tanaka, K., and E. Nishi. 2008. Habitat use by the gnathiid isopod Elaphognathia discolor living in terebellid polychaete tubes. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 88(1): 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315408000039.

Thiel, M. 2003. Reproductive biology of Limnoria chilensis: another boring peracarid species with extended parental care. Journal of Natural History 37(14): 1713–1726. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222930210125416.

Thiel, M. 2011. The evolution of sociality: peracarid crustaceans as model organisms. New Frontiers in Crustacean Biology. Proceedings of the TCS Summer Meeting, Tokyo, 20-24 September 2009. Crustaceana Monographs 15: 285–297.

Thompson, M.T. 1902. A new isopod parasitic on the hermit crab. Bulletin of the U.S Fisheries Commission 21: 53–56.

Torres Jordá, M. 2003. Estudio de la relación entre el parásito Leidya distorta (Isopoda: Bopyridae) y su hospedador Uca uruguayensis (Brachyura: Ocypodidae), y descripción de los estadíos larvales de L. distorta. Unpublished PhD thesis. Buenos Aires: Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Ueda, H., A. Kuwahara, N. Tanaka, and M. Azeta. 1983. Underwater observations on copepod swarms in temperate and subtropical waters. Marine Ecology Progress Series 11: 165–171. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps011165.

Uye, S., and A. Murase. 1997. Infertility of the planktonic copepod Calanus sinicus caused by parasitism by a larval epicaridian isopod. Plankton Biology and Ecology 44(1/2): 97–99.

Vršanský, P., I. Koubová, L. Vršanská, J. Hinkelman, M. Kúdela, T. Kúdelová, J.H. Liang, F. Xia, X. Lei, X. Ren, Ľ Vidlička, T. Bao, S. Ellenberger, L. Šmídová, and M. Barclay. 2019. Early wood-boring ‘mole roach’ reveals eusociality “missing ring.” AMBA Projekty 9(1): 1–28.

Wägele, J.W. 1989. Evolution und phylogenetisches System der Isopoda: Stand der Forschung und neue Erkenntnisse. Zoologica. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart.

Walossek, D. 1999. On the Cambrian Diversity of Crustacea. In Crustaceans and the Biodiversity Crisis, eds. F.R. Schram, and J.C. von Vaupel Klein, 3–27. Proceedings of the Fourth International Crustacean Congress. Leiden: Brill.

Walossek, D., and K.J. Müller. 1998. Cambrian ‘Orsten’-type arthropods and the phylogeny of Crustacea. In Arthropod relationships, eds. R.A. Fortey and R.H. Thomas, 139–153. Dordrecht: Springer.

Wang, B., J. Rust, M.S. Engel, J. Szwedo, S. Dutta, A. Nel, Y. Fan, F. Meng, G. Shi, E.A. Jarzembowski, T. Wappler, F. Stebner, Y. Fang, L. Mao, D. Zheng, and H. Zhang. 2014. A diverse paleobiota in early Eocene fushun amber from China. Current Biology 24(14): 1606–1610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.048.

Wang, H., M. Schädel, B. Sames, and D.J. Horne. 2020. New record of podocopid ostracods from Cretaceous amber. PeerJ e10134: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10134.

Weitschat, W., and W. Wichard. 1998. Atlas der Pflanzen und Tiere im Baltischen Bernstein. München: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil.

Wichard, W., and W. Weitschat. 2004. Im Bernsteinwald. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg.

Wienberg Rasmussen, H., S.L. Jakobsen, and J.S.H. Collins. 2008. Raninidae infested by parasitic Isopoda (Epicaridea). Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum 34: 31–49.

Williams, J.D., and J. An. 2009. The cryptogenic parasitic isopod Orthione griffenis Markham, 2004 from the eastern and western Pacific. Integrative and Comparative Biology 49(2): 114–126.

Wilson, G.D.F. 2009. The phylogenetic position of the Isopoda in the Peracarida (Crustacea: Malacostraca). Arthropod Systematics and Phylogeny 67(2): 159–198.

Wilson, G.D.F., and R.T. Johnson. 1999. Ancient endemism among freshwater isopods (Crustacea, Phreatoicidea). In The other 99%: the conservation and biodiversity of invertebrates, ed. W. Ponder, 264–268. New South Wales: Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales. https://doi.org/10.7882/0958608512.

Wings, O., M. Rabi, J.W. Schneider, L. Schwermann, G. Sun, C.F. Zhou, and W.G. Joyce. 2012. An enormous Jurassic turtle bone bed from the Turpan Basin of Xinjiang, China. Naturwissenschaften 99(11): 925–935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-012-0974-5.

Wu, R.J.C. 1997. Secrets of a lost world. Dominican amber and its inclusions. Santo Domingo