Abstract

Background

Environmental factors may contribute to short sleep duration and irregular bedtime in children. Neighborhood factors and children’s sleep duration and bedtime regularity remain a less investigated area. The aim of this study was to investigate the national and state-level proportions of children with short sleep duration and irregular bedtime and their neighborhood predictors.

Methods

A total of 67,598 children whose parents completed the National Survey of Children’s Health in 2019–2020 were included in the analysis. Survey-weighted Poisson regression was used to explore the neighborhood predictors of children’s short sleep duration and irregular bedtime.

Results

The prevalence of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime among children in the United States (US) was 34.6% [95% confidence interval (CI) = 33.8%–35.4%] and 16.4% (95% CI = 15.6%–17.2%) in 2019–2020, respectively. Safe neighborhoods, supportive neighborhoods, and neighborhoods with amenities were found to be protective factors against children’s short sleep duration, with risk ratios ranging between 0.92 and 0.94, P < 0.05. Neighborhoods with detracting elements were associated with an increased risk of short sleep duration [risk ratio (RR) = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.00–1.12] and irregular bedtime (RR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.03–1.28). Child race/ethnicity moderated the relationship between neighborhood with amenities and short sleep duration.

Conclusions

Insufficient sleep duration and irregular bedtime were highly prevalent among US children. A favorable neighborhood environment can decrease children’s risk of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime. Improving the neighborhood environment has implications for children’s sleep health, especially for children from minority racial/ethnic groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Poor sleep health has been increasingly recognized as an important public health issue due to its prevalence and negative consequences among both adults and children [1]. Sleep health includes various domains of sleep characteristics, including regularity, alertness, timing, efficiency, and satisfaction [2]. It is estimated that every one of four children suffers from poor sleep health, ranging from short sleep duration, frequent night waking, sleep resistance, and daytime sleepiness to more severe sleep disorders, including insomnia and sleep apnea [3]. Poor sleep health may contribute to poor physical health, poor mental health, and behavior problems in children [4]. Specifically, insufficient sleep duration is associated with increased child body mass index and obesity [5], poor executive functioning and school performance [6, 7], and increased risk for major depression [8], while regular bedtime contributes to children’s nighttime sleep consolidation and adolescents’ longer sleep duration and less daytime fatigue [9,10,11].

In recent years, various physical and social environmental factors have been recognized to impact child sleep health [12]. Socioeconomic status (SES) is one particular factor that has been increasingly studied [13]. Specifically, racial and ethnic minority children have a higher risk of insufficient sleep duration and poorer sleep quality [14]. Low SES, such as poverty, low educational attainment, poor family environment and poor neighborhood conditions, are predictive of poor sleep quality from early childhood to adolescence [15].

Among societal and environmental factors, neighborhood factors also play a role in shaping children’s sleep health [16]. A study conducted in Canada found that children with obstructive sleep apnea were more likely to reside in disadvantaged neighborhoods characterized by a higher level of poverty, higher population density, and a higher proportion of single-parent households [17]. Singh and colleagues also found that unfavorable neighborhoods (neighborhoods with safety concerns, garbage/litter in street, poor housing, or vandalism) were associated with a higher prevalence of serious sleep problems among children in the United States (US) [18]. It remains unclear whether the association between neighborhood social capital and built environments and children’s sleep health still exists in more recent years. Furthermore, neighborhood effects are beyond the concentration of poverty and consist of multiple salient dimensions of the residential setting [19]. In fact, physical and social environmental factors could influence sleep health [20]. People living in neighborhoods with lower SES may have poorer housing conditions and a greater risk of being exposed to light, noise, air pollution, etc. Thus, research on the prevalence of poor child sleep health and its wider and multi-dimensional neighborhood and societal predictors is warranted.

Previous research has found that the geographic distribution of insufficient sleep in the US adult population was uneven [21, 22]. Most variabilities in sleep duration across different neighborhoods are explained by both family-level SES and neighborhood-level SES [22]. Recently, a study found that the prevalence of short sleep duration was also uneven in the US child population during 2016–2018, with southeastern states having a higher prevalence [23]. It remains unclear whether this trend persists when several national campaigns and programs have been installed to target child sleep health [24].

Given the importance of neighborhood factors on child sleep health and given that sleep duration and regularity are two important dimensions that are highly relevant for pediatrics and children’s optimal sleep health [11], we aim to utilize the most recent data from the 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to investigate the relationship between neighborhood factors and children’s short sleep duration and irregular bedtime.

Methods

Data sources and participants

This study used the NSCH 2019–2020 two-year combined dataset. The NSCH was a population-based nationally representative survey of parents of children aged 0–17 years in the US. It was initially conducted every four years in 2003, 2007, and 2011/12, followed by every year starting from 2016 to 2020. The main purpose of this survey was to estimate the national and state-level prevalence of a wide range of child and family health outcomes to facilitate policies and health advocacy. The current study used the most recent two-year iteration and released public use dataset: NSCH 2019–2020. The NSCH 2019 was conducted from June 2019 to January 2020, with a total of 29,433 children whose parents completed the survey. Regarding NSCH 2020, the survey was conducted between July 2020 and January 2021, with a total of 42,777 children whose parents completed the survey. The survey data were weighted by the NSCH team to reflect the demographic characteristics of non-institutional children and adolescents aged 0–17 years in each state [25]. The NSCH 2019–2020 public use data can be found at the United States Census Bureau website (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/data/datasets.html).

Participants were US households with child(ren). Potential eligible households received a mail screener invitation asking if there was any child living in the household and if the adult was familiar with the child(ren)’s condition. Parents were later invited to answer the child age-specific topical questionnaires via web or paper if they were identified as eligible for the NSCH [25]. The main topical questions include child and family demographics, physical and mental health status, access to health care, health insurance status, type, and adequacy, and family health and activities, among others.

Explanatory variables

Explanatory variables were generated using the following four neighborhood factors: safe neighborhoods, supportive neighborhoods, neighborhoods with detracting elements, and neighborhoods with amenities.

Safe neighborhoods were assessed by asking the parents one question: how much do you agree that this child is safe in your neighborhood?, with four answers: 1 = definitely agree, 2 = somewhat agree, 3 = somewhat/definitely disagree. Children whose parents answered “definitely agree” were rated as living in a safe neighborhood.

Supportive neighborhoods were assessed with one variable generated by the NSCH research team: does this child live in a supportive neighborhood? The variable was derived from parental responses to three statements: (1) people in this neighborhood help each other out; (2) we watch out for each other's children in this neighborhood; and (3) when we encounter difficulties, we know where to go for help in our community. Parents were asked whether they definitely agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or definitely disagree with each statement. Children were considered to live in supportive neighborhoods if their parents reported “definitely agree” to at least one of the items above and “somewhat agree” or “definitely agree” to the other two items. Only children whose parents submitted valid responses to all three items are included in the denominator.

Neighborhoods with detracting elements were assessed with one question: in this child’s neighborhood, how many detracting elements—litter or garbage on the street or sidewalk, poorly kept or rundown housing, or vandalism—are there?, with three answers: 0 = none, 1 = 1 detracting element, 2 = 2 detracting elements, 3 = 3 detracting elements. Children were rated as living in a neighborhood with detracting elements if their parents did not answer “none”.

Neighborhood amenities were assessed with the following question: in this child’s neighborhood, how many amenities—parks, recreation centers, sidewalks or libraries—does it contain?, with four answers: 0 = none, 1 = 1 amenity, 2 = 2 amenities, 3 = 3 amenities, 4 = all 4 amenities. Children were rated as living in a neighborhood with amenities if their parents answered any above number except for 0.

Outcome variables

Two variables were included as the outcome variables: short sleep duration and irregular bedtime. The first outcome variable evaluated whether or not each child had short sleep duration, which was generated based on one question answered by the parents: during the past week, how many hours of sleep did this child get during an average day count both nighttime sleep and naps for children aged 0–5 years? For children aged 6–17 years, the question was adjusted as follows: during the past week, how many hours of sleep did this child get on most weeknights? The question had seven answers: 1 = less than 6 hours, 2 = 6 hours, 3 = 7 hours, 4 = 8 hours, 5 = 9 hours, 6 = 10 hours, and 7 = 11 or more hours. Short sleep duration was defined based on child age and the appropriate sleep duration recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine [26]. Specifically, short sleep duration was defined as < 12 hours (including naps) for infants aged 4–11 months, < 11 hours (including naps) for children aged 1–2 years, < 10 hours (including naps) for children aged 3–5 years, < 9 hours for children aged 6–12 years, and < 8 hours for adolescents aged 13–17 years [25].

The second outcome variable was bedtime irregularity, which was captured by one question answered by parents: how often does this child go to bed at about the same time on weeknights?, with answers ranging from always, usually, sometimes to rarely or never. Children whose parents answered “always” or “usually” to this question were classified as having regular bedtime, while others were classified as having irregular bedtime.

Covariates

Based on previous literature, children and parental characteristics shown to be correlated with children’s sleep health, such as children’s age [27], gender [28], race/ethnicity [29], and parental SES status [30], and when these variables were collected in the NSCH, were included in the analysis. Specifically, children’s age group (0–5 years, 6–11 years, and 12–17 years), gender (male, and female), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, and other/multiracial non-Hispanic), their parents or caregivers’ highest education (less than high school, high school, some college or technical school, and college degree or higher), and household income level [< 99% federal poverty level (FPL), 100%–199% FPL, 200%–399% FPL, and ≥ 400% FPL] were included as covariates. Furthermore, survey year (2019 vs. 2020) was included as a covariate to explore whether children’s sleep duration and bedtime regularity significantly changed before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Data analysis

The national and state-level estimates of the percent of short sleep duration, percent of irregular bedtime, and other demographic characteristics were survey-weighted to make descriptive estimates that were representative of the national demographics. A survey-weighted Chi-square test was used to investigate group differences regarding demographic characteristics in children with and without short sleep duration and children with and without irregular bedtime. Less than 5% of children had missing values in the variables used in this study; thus, these children were excluded from the analysis. A total of 67,598 children aged 4 months to 17 years with complete data on neighborhood factors, covariates, and short sleep duration were included in the analysis of the relationship between neighborhood factors and children’s short sleep duration. Considering that irregular bedtime is common among infants and toddlers, we only included children older than 5 years old with complete data on neighborhood factors, covariates, and irregular bedtime (n = 48,941) to analyze the relationship between neighborhood factors and children’s irregular bedtime.

Multivariable Poisson regression was conducted to investigate the association between neighborhood factors and children’s short sleep duration and irregular bedtime. All analyses were adjusted for complex survey design. The interaction terms of each neighborhood factor and child age group, gender, and race/ethnicity were tested to explore whether these demographic factors were moderators. The Wald test was used to investigate if the interaction term was statistically significant. Only race/ethnicity was found to be a significant moderator for certain neighborhood factors and children’s short sleep duration and irregular bedtime. When a statistically significant moderation effect was detected, subgroup analysis was conducted. The statistical software R (version 4.0.2) was used for all analyses. The “survey” package [31] was used for logistic regression. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Compared to children in younger age groups, older children (aged 12–17 years) had the lowest proportion of insufficient sleep duration [32.0%, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 30.8%–33.2%] and a higher proportion of irregular bedtime (21.1%, 95% CI = 19.9%–22.3%). In general, children from non-White race/ethnic groups whose parents had lower educational attainment and with lower household income levels had higher proportions of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime. The proportion of children with irregular bedtime was significantly higher in 2020 (during the COVID-19 pandemic) than in 2019 (before the pandemic) (Table 1).

Prevalence of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime

The overall national prevalence of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime among US children in 2019–2020 was 34.6% (95% CI = 33.8%–35.4%) and 16.4% (95% CI = 15.6%–17.2%), respectively. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a, southern states such as Alabama (42.2%), Arkansas (45.1%), Louisiana (47.4%), and Mississippi (47.0%) had the highest prevalence of short sleep duration, while northern states such as Minnesota (23.1%) and Maine (28.0%) had the lowest prevalence. Similarly, the prevalence of irregular bedtime was among the highest in the southern region (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Specifically, Los Angeles (22.4%) has the highest prevalence of irregular bedtime in children, followed by the District of Columbia (22.2%) and Mississippi (22.1%).

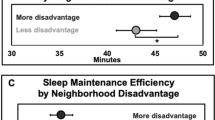

Predictors of short sleep duration

Controlling for covariates, safe neighborhood, supportive neighborhood, and neighborhood with amenities were all found to be protective factors of children’s short sleep duration, with risk ratios (RR) ranging between 0.92 and 0.94 (P < 0.05), indicating that these neighborhood factors were associated with an approximately 6%–8% lower risk of a child getting insufficient sleep duration (Table 2). A neighborhood with detracting elements was found to be associated with a 1.06-fold increase in the likelihood of having a short sleep duration (RR = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.00–1.12). The association between neighborhood amenities and short sleep duration was moderated by children’s race/ethnicity (Wald test for interaction term Chi-square = 11.23, P = 0.007), such that neighborhood amenities were associated with a decreased risk of short sleep duration for White children (RR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.80–0.93, P < 0.001) but an increased risk for Hispanic children (RR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.00–1.62, P < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Predictors of irregular bedtime

After adjusting for child‒parent dyads’ demographic covariates, living in a neighborhood with detracting elements was associated with a 1.15-fold increased risk of having irregular bedtime. Both safe neighborhoods and supportive neighborhoods were associated with a decreased risk of irregular bedtime (Table 2). Neighborhood with amenities had no statistically significant relationship with children’s irregular bedtime (RR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.81–1.08). No moderating relationship was found between parental SES factors, neighborhood factors, and school-aged children’s irregular bedtime.

Discussion

This study investigated the latest national prevalence of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime among US children, as well as their neighborhood predictors based on the NSCH 2019–2020 data. The results showed that the national prevalence of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime among US children remained generally high in 2019–2020, affecting around 34.6% of children and 16.4% of children, respectively. Favorable neighborhood environments (safe neighborhood and supportive neighborhood) were protective factors against children’s short sleep duration and irregular bedtime. Negative neighborhood factor (neighborhood with detracting elements) was associated with children’s short sleep duration and irregular bedtime.

Prevalence of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime

The national prevalence of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime in the US child population were 34.6% and 16.4% in 2019–2020, respectively, similar to the national prevalence found in previous years (34.9% for insufficient sleep in 2016–2018 [23] and 14.5% for irregular sleep in 2017–2018 [32]). Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi were among the states with the highest prevalence (> 41%) of insufficient sleep duration, similar to the pattern found in the NSCH 2016–2018 [23].

The distribution of state-level irregular bedtime prevalence was generally similar to the distribution of short sleep duration. Specifically, southern states, including Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, had the highest prevalence (> 20%) of irregular bedtime. Interestingly, states such as Alabama and Arkansas had the highest prevalence of short sleep duration yet had the lowest prevalence or irregular bedtime. The exact reason for this discrepancy between the distribution of irregular bedtime and short sleep duration within the same state is unclear, although it could be due to the subjective nature of these two outcome variables and thus may include recall bias.

Favorable neighborhoods

In the current study, safe neighborhoods were found to be a protective factor against children’s short sleep duration. This is in line with previous studies that found an association between neighborhood safety and sleep in both adults [33] and children [18]. A recent systematic review also found that parent- or caregiver-reported neighborhood unsafety was associated with adverse child sleep outcomes [34]. Beyond subjectively reported sleep measures, neighborhood safety was also associated with actigraph-assessed time in bed and sleep duration in adolescents [35]. Worries about community safety and violence may lead to psychological and physiological arousal and a stressful state and thus lead to difficulty in attaining high-quality and regular sleep [36].

Supportive neighborhoods were also found to decrease the risk of children’s short sleep duration and irregular bedtime. Perceived supportive neighborhood may reflect that a family had more resources to look for help when needed to keep family routine and children’s regular bedtime. There are several potential reasons that living in a favorable neighborhood can protect children’s sleep health. First, a favorable neighborhood generally has higher neighborhood SES and a better surrounding environment, such as lower noise [37] and air pollution [38], which have both been identified as robust predictors for child sleep [12]. Another potential reason is that children who live in favorable neighborhoods are likely to engage in more outdoor physical activities [39] and less screen time [40]. Physical activity is associated with decreased sleep latency for school-aged children [41] and increased slow-wave sleep [42], which then can increase sleep duration.

Unfavorable neighborhoods

We found that neighborhood with detracting elements (litter or garbage on the street or sidewalk, poorly kept or rundown housing, or vandalism) was a risk factor for both short sleep duration and irregular bedtime. Previous research documented that unfavorable neighborhood factors such as neighborhood poverty were associated with worse health outcomes such as obesity [43]. Indeed, neighborhoods with unfavorable environments often have limited resources to improve their built environment, which can contribute to children’s sleep health. Specifically, detracting elements in neighborhoods are associated with less favorable social environments, such as less social cohesion and social capital and increased crime rates [43].

Race/ethnicity moderation

We found that child race/ethnicity moderated the relationship between neighborhood with amenities and short sleep duration, highlighting the importance of race/ethnicity in shaping children’s sleep health. Thus, policy makers should consider the implications of advocating a favorable neighborhood environment for minority children. A recent literature review found that compared to White non-Hispanic children, Black and other race/ethnic minority children generally went to bed later, had shorter sleep durations, and napped more often [44]. Health literacy may also contribute to this relationship. Black and other race/ethnic minority parents were less likely to be aware of the recommended child age-appropriate sleep duration and to overestimate sleep sufficiency in their children [14].

Interestingly, the moderation effect of race/ethnicity on neighborhood amenities and short sleep duration was only significant among Hispanic and White children, and neighborhood amenities acted as a risk factor for Hispanic children. A possible reason for this was that the percent of neighborhood amenity was a surrogate of other underlying neighboring disadvantage factors, such as greater population densities and higher proportions of single mothers [17].

Strengths and limitations

There were several limitations in this study. First, all variables were parent- or caregiver-reported and thus may include recall bias. Second, the cross-sectional survey cannot draw causal relationships between neighborhood factors and child sleep health. Third, home environmental factors that may influence children’s sleep health, such as parenting quality and interpersonal factors such as interparental conflicts [13], were not included in this study. Fourth, state was the only geographic variable available in the NSCH public use dataset, while more nuanced geographic variables such as census tracts were not available. Using state as the random intercept in multilevel Poisson regression, we found that state explained little variance in children’s sleep duration [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) = 0.01] and bedtime irregularity (ICC = 0.01) (Supplementary Table 1). Thus, we were not able to investigate whether the effects of neighborhood factors on children’s sleep duration and bedtime regularity vary across different geographic areas. Despite these limitations, this study provided the latest national and state-level prevalence of child sleep duration and irregular bedtime and was the first to explore the race/ethnicity moderation effect on the relationship between multiple neighborhood factors and child sleep duration and bedtime regularity. Future studies should include wider societal and geographic explanatory factors, consider incorporating both objective and subjective measures of child sleep and neighborhood effects, and employ a longitudinal design.

In conclusion, this study found that the national prevalence of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime among US children remained generally high in 2019 and 2020. A favorable neighborhood environment was associated with children’s short sleep duration and irregular bedtime. The findings suggest that both physical and social environment factors contribute to child sleep health and highlight the importance of social determinants of health. Public health initiatives should design targeted interventions to improve the community and neighborhood social and physical environment to improve child sleep health, especially for those with a higher prevalence of short sleep duration and irregular bedtime places and those at higher risk.

Data availability

The National Survey of Children’s Health 2019–2020 public use data can be found at the United States Census Bureau website: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/data/datasets.html.

References

Hale L, Troxel W, Buysse DJ. Sleep health: an opportunity for public health to address health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:81–99.

Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 2014;37:9–17.

Owens JA. Behavioral sleep problems in children. UpToDate. 2020. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/behavioral-sleep-problems-in-children. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

Liu J, Ji X, Pitt S, Wang G, Rovit E, Lipman T, et al. Childhood sleep: physical, cognitive, and behavioral consequences and implications. World J Pediatr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00647-w.

Matricciani L, Bin YS, Lallukka T, Kronholm E, Dumuid D, Paquet C, et al. Past, present, and future: trends in sleep duration and implications for public health. Sleep Health. 2017;3:317–23.

Chaput JP, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, Carson V, Gruber R, Olds T, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:S266–82.

Prichard JR. Sleep predicts collegiate academic performance: implications for equity in student retention and success. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15:59–69.

Roberts RE, Duong HT. The prospective association between sleep deprivation and depression among adolescents. Sleep. 2014;37:239–44.

Short MA, Gradisar M, Wright H, Lack LC, Dohnt H, Carskadon MA. Time for bed: parent-set bedtimes associated with improved sleep and daytime functioning in adolescents. Sleep. 2011;34:797–800.

Peltz JS, Rogge RD, Connolly H. Parents still matter: the influence of parental enforcement of bedtime on adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Sleep. 2020;43:zsz287.

Meltzer LJ, Williamson AA, Mindell JA. Pediatric sleep health: it matters, and so does how we define it. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;57:101425.

Liu J, Ghastine L, Um P, Rovit E, Wu T. Environmental exposures and sleep outcomes: a review of evidence, potential mechanisms, and implications. Environ Res. 2021;196:110406.

Doane LD, Breitenstein RS, Beekman C, Clifford S, Smith TJ, Lemery-Chalfant K. Early life socioeconomic disparities in children’s sleep: the mediating role of the current home environment. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48:56–70.

Guglielmo D, Gazmararian JA, Chung J, Rogers AE, Hale L. Racial/ethnic sleep disparities in US school-aged children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Sleep Health. 2018;4:68–80.

Counts CJ, Grubin FC, John-Henderson NA. Childhood socioeconomic status and risk in early family environments: predictors of global sleep quality in college students. Sleep Health. 2018;4:301–6.

Grandner MA, Fernandez FX. The translational neuroscience of sleep: a contextual framework. Science. 2021;374:568–73.

Brouillette RT, Horwood L, Constantin E, Brown K, Ross NA. Childhood sleep apnea and neighborhood disadvantage. J Pediatr. 2011;158:789–95.e1.

Singh GK, Kenney MK. Rising prevalence and neighborhood, social, and behavioral determinants of sleep problems in US children and adolescents, 2003–2012. Sleep Disord. 2013;2013:394320.

Faber JW, Sharkey P. Neighborhood effects. In: Wright JD, editor. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 2nd edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. p. 443-449.

Billings ME, Hale L, Johnson DA. Physical and social environment relationship with sleep health and disorders. Chest. 2020;157:1304–12.

Grandner MA, Smith TE, Jackson N, Jackson T, Burgard S, Branas C. Geographic distribution of insufficient sleep across the United States: a county-level hotspot analysis. Sleep Health. 2015;1:158–65.

Fang SC, Subramanian SV, Piccolo R, Yang M, Yaggi HK, Bliwise DL, et al. Geographic variations in sleep duration: a multilevel analysis from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:63–9.

Wheaton AG, Claussen AH. Short sleep duration among infants, children, and adolescents aged 4 months-17 years—United States, 2016–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1315–21.

Start School Time Later. Position statements and resolutions on sleep and school start times. 2021. https://www.startschoollater.net/position-statements.html. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. NSCH Codebooks. 2018–2019 National Survey of Children’s Health (2 years combined data set): STATA codebook. Version 1.0. Child and family health measures, national performance and outcome measures, and subgroups. https://www.childhealthdata.org/learn-about-the-nsch/nsch-codebooks. Accessed 13 Dec 2021.

Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, Hall WA, Kotagal S, Lloyd RM, et al. Consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine on the recommended amount of sleep for healthy children: methodology and discussion. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:1549–61.

Carter KA, Hathaway NE, Lettieri CF. Common sleep disorders in children. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:368–77.

Uebergang LK, Arnup SJ, Hiscock H, Care E, Quach J. Sleep problems in the first year of elementary school: the role of sleep hygiene, gender and socioeconomic status. Sleep Health. 2017;3:142–7.

Becker SP, Sidol CA, Van Dyk TR, Epstein JN, Beebe DW. Intraindividual variability of sleep/wake patterns in relation to child and adolescent functioning: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:94–121.

Musić Milanović S, Buoncristiano M, Križan H, Rathmes G, Williams J, Hyska J, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep patterns among 6- to 9-year-old children from 24 countries in the WHO European region. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 6):e13209.

Lumley T. Package "survey": analysis of complex survey samples. Vienna: R Core Team; 2020.

Ji X, Covington LB, Patterson F, Ji M, Brownlow JA. Associations between sleep and overweight/obesity in adolescents vary by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. J Adv Nurs. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15513.

Johnson DA, Simonelli G, Moore K, Billings M, Mujahid MS, Rueschman M, et al. The neighborhood social environment and objective measures of sleep in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2017;40:zsw016.

Mayne SL, Mitchell JA, Virudachalam S, Fiks AG, Williamson AA. Neighborhood environments and sleep among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;57:101465.

Fuller-Rowell TE, Nichols OI, Robinson AT, Boylan JM, Chae DH, El-Sheikh M. Racial disparities in sleep health between Black and White young adults: the role of neighborhood safety in childhood. Sleep Med. 2021;81:341–9.

Bagley EJ, Tu KM, Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M. Community violence concerns and adolescent sleep. Sleep Health. 2016;2:57–62.

Basner M, McGuire S. WHO environmental noise guidelines for the European region: a systematic review on environmental noise and effects on sleep. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:519.

Bose S, Ross KR, Rosa MJ, Chiu YM, Just A, Kloog I, et al. Prenatal particulate air pollution exposure and sleep disruption in preschoolers: windows of susceptibility. Environ Int. 2019;124:329–35.

Gillis BT, Shimizu M, Philbrook LE, El-Sheikh M. Racial disparities in adolescent sleep duration: physical activity as a protective factor. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2021;27:118–22.

Hale L, Guan S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;21:50–8.

Nixon GM, Thompson JM, Han DY, Becroft DM, Clark PM, Robinson E, et al. Falling asleep: the determinants of sleep latency. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:686–9.

Kalak N, Gerber M, Kirov R, Mikoteit T, Yordanova J, Pühse U, et al. Daily morning running for 3 weeks improved sleep and psychological functioning in healthy adolescents compared with controls. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:615–22.

Suglia SF, Shelton RC, Hsiao A, Wang YC, Rundle A, Link BG. Why the neighborhood social environment is critical in obesity prevention. J Urban Health. 2016;93:206–12.

Smith JP, Hardy ST, Hale LE, Gazmararian JA. Racial disparities and sleep among preschool aged children: a systematic review. Sleep Health. 2019;5:49–57.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DY contributed to research design, statistical analysis, and original draft writing. LJ contributed to conceptualization, research design, writing, review, and editing. Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This analysis of an anonymous public data set was determined exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania. The National Survey of Children’s Health data collection was approved by the US National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board and the Associates Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of interest

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, Y., Liu, J. Neighborhood predictors of short sleep duration and bedtime irregularity among children in the United States: results from the 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health. World J Pediatr 20, 73–81 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-023-00694-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-023-00694-x