Abstract

Introduction

Available short-acting intrathecal anesthetic agents (chloroprocaine and prilocaine) offer an alternative to general anesthesia for short-duration surgical procedures, especially ambulatory surgeries. Factors determining the choice of anesthesia for short-duration procedures have not been previously identified.

Methods

This observational, prospective, multicenter, cohort study was conducted between July 2015 and July 2016, in 33 private or public hospitals performing ambulatory surgery. The primary objective was to determine the factors influencing the choice of anesthetic technique (spinal or general anesthesia). Secondary outcomes included efficacy of the anesthesia, time to hospital discharge, and patient satisfaction.

Results

Among 592 patients enrolled, 309 received spinal anesthesia and 283 underwent general anesthesia. In both study arms, the most frequently performed surgical procedures were orthopedic and urologic (43.3% and 30.7%, respectively); 66.1% of patients were free to choose their type of anesthesia, 21.8% chose one of the techniques because they were afraid of the other, 16.8% based their choice on the expected ease of recovery, 19.2% considered their degree of anxiety/stress, and 16.9% chose the technique on the basis of its efficacy. The median times to micturition and to unassisted ambulation were significantly shorter in the general anesthesia arm compared with the spinal anesthesia arm (225.5 [98; 560] min vs. 259.0 [109; 789] min; p = 0.0011 and 215.0 [30; 545] min vs. 240.0 [40; 1420]; p = 0.0115, respectively). The median time to hospital discharge was equivalent in both study arms. In the spinal anesthesia arm, patients who received chloroprocaine and prilocaine recovered faster than patients who received bupivacaine. The time to ambulation and the time to hospital discharge were shorter (p < 0.001). The overall success rate of spinal anesthesia was 91.6%, and no significant difference was observed between chloroprocaine, prilocaine, and bupivacaine. The patients’ global satisfaction with anesthesia and surgery was over 90% in both study arms.

Conclusions

Patient’s choice, patient fear of the alternative technique, patient stress/anxiety, the expected ease of recovery, and the efficacy of the technique were identified as the main factors influencing patient choice of short-acting local anesthesia or general anesthesia. Spinal anesthesia with short-acting local anesthetics was preferred to general anesthesia in ambulatory surgeries and was associated with a high degree of patient satisfaction.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02529501. Registered on June 23, 2015. Date of enrollment of the first participant July 21, 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Need for an alternative anesthesia technique for reducing the time of motor blockade in ambulatory surgeries. |

Factors leading to the use of general anesthesia and short-duration procedures are not defined, for physicians and patients. |

What was learned from the study? |

Patient’s choice, patient’s fear of the other technique, patient’s stress/anxiety status, the expected quality of recovery, and the efficacy of the technique were identified as main factors influencing the patient choice between short-acting local anesthetics and general anesthesia. |

Spinal anesthesia with short-acting local anesthetics has been preferred to general anesthesia in ambulatory surgeries and conveyed a high degree of patient satisfaction. |

Introduction

In 2015, ambulatory surgeries accounted for up to 70% of surgical procedures in the USA, but only 52% in France [1]. General anesthesia has been recommended to ensure a relatively rapid onset of action and to reduce procedure-related stress. But the prolongation of motor blockade may increase the length of time in hospital and some side effects may complicate patient management [2].

One of the main criteria for choosing the type of anesthesia is the ease of postoperative recovery, including control of postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, and urinary retention. These side effects may delay hospital discharge or result in unplanned readmission. Spinal anesthesia is a simple and reliable technique with a success rate of over 90% [3,4,5,6]. However, general anesthesia is commonly preferred because of its faster onset of action [2]. Spinal anesthesia is also associated with a better control of postoperative nausea and vomiting [7] and a higher possibility of early discharge [8, 9]. In orthopedic surgery, the efficacy of spinal anesthesia is comparable to general anesthesia [10] and has been shown to be associated with fewer short-term complications [11, 12].

In addition, spinal anesthesia is considered to be less cost-effective for some procedures, such as inguinal hernia repair [13] or lumbar spine surgery [14]. There is no morbidity or mortality evidence in favor of either spinal anesthesia or general anesthesia [15].

Because of the occurrence of transient neurologic symptoms following spinal anesthesia with lidocaine, intrathecal lidocaine administration has been discontinued [16,17,18,19,20]. Low-dose bupivacaine was the standard in Europe for spinal anesthesia for short-duration procedures until 2% chloroprocaine became available in 2013, followed by 2% prilocaine in 2014. Chloroprocaine is a short-acting local anesthetic agent and has a non-inferior efficacy to low-dose spinal bupivacaine [21, 22]. A hyperbaric solution of prilocaine is associated with a shorter onset of sensory block at the T10 level, compared with standard prilocaine [5], and has been demonstrated to have a good efficacy [5, 23, 24]. These two short-acting local anesthetic agents (chloroprocaine and prilocaine) offer alternative options that may influence the choice of spinal or general anesthesia in ambulatory surgeries. The use of spinal or general anesthesia also depends on surgical procedures (anesthetist and surgeon skill), the patient’s medical status (age, comorbidities, etc.), and other related factors (anxiety, fear of not waking up) [25, 26].

The aim of this cross-sectional, observational, prospective, multicenter study conducted in France was to identify the factors determining the choice of anesthesia (spinal anesthesia or short general anesthesia) for ambulatory surgeries.

Methods

This national, observational, prospective, multicenter study was conducted between July 2015 and July 2016 in France, in both public and private hospitals providing ambulatory surgery facilities. The study was approved by the Sud-Mediterranée IV (Hôpital Saint Eloi, Montpellier, France) Ethics Committee on June 23, 2015 and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02529501). Up to 30 consecutive patients scheduled for ambulatory surgeries were included in each center. Every patient gave oral consent after receiving full oral and written information about their data collection and the use of their personal information. The patient population included adults undergoing ambulatory surgeries with either general or spinal anesthesia who were able to complete a self-administered questionnaire. Patients with contraindications to ambulatory surgery, patients who underwent emergency surgery, patients with contraindications to spinal anesthesia (due to surgical procedure site, comorbidities, or particular treatments), and patients participating or enrolled in another clinical trial 1 month preceding the study were excluded.

During pre-anesthetic consultation, a key moment for the exchange of information between the physician and the patient, physicians filled in a questionnaire to record additional clinical items including the patient’s medical status, type of surgery, type of anesthesia, criteria influencing the choice of anesthesia (surgery, anesthesia, surgeon, and other criteria identified by the physician) graded on a scale of four (deciding factor, very important, quite important, not important) and postoperative data.

General anesthesia was performed by inhalation (using a laryngeal mask or orotracheal intubation) or by intravenous administration. Hypnotic, morphinic, curare, or halogenated agents were used as anesthetics.

The local anesthetics used for spinal administration were bupivacaine 5 mg/ml, prilocaine 20 mg/ml, chloroprocaine 10 mg/ml, and ropivacaine, either in a hyperbaric or isobaric solution. Different types of needles were used for spinal anesthesia (Whitacre, sprocket, double bevel, and others) of different gage sizes (24, 25, 26, 27, and others). Some patients received sedatives, treatments for hypotension, or other drugs, as pretreatment to spinal anesthesia. Psycholeptics (benzodiazepine derivates, diphenylmethane derivates), anesthetics, and analgesics were used as sedatives. Ephedrine was administered to manage hypotension during anesthesia. Other medication administered to specific patients included medication for acid-related disorders; blood substitutes and perfusion solutions; antiarrhythmics and adrenergic agents; opioid anesthetics; anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products; and glucocorticoids, among others.

Eligibility for hospital discharge (complete regression of sensory block, spontaneous voiding, ability to walk, stable vital signs, no nausea, control of pain with oral treatment, ability to swallow liquids) was described as an average overall time for each patient. Additional data about the patient’s pain perception and satisfaction were collected using a self-administered questionnaire 7 days after surgery. Patients were asked to score the most severe pain during this period and their current pain, using a visual analog scale from 0 to 10.

The primary objective was to determine the factors influencing the choice of the anesthetic technique.

A minimum of 277 patients in each arm was required to achieve statistical significance with a power of 95% at the following level of significance: 6% for a criterion judged as deciding and reported in 50% of patients in one of the groups and 5% for a criterion judged as deciding and reported in 25% of patients in one of the arms: 554 patients were expected. Statistical analysis was performed with version 9.1 or later of the SAS® software (SAS Institute, NC, Cary, USA). The Mann–Whitney test, Krustal–Wallis test, and Student t test were used for continuous variables. The chi-squared test was used for categorical variables. All p values were two-sided. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

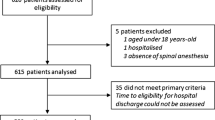

Thirty-three centers participated in the study and included a total of 594 patients (mean 18.0 ± 10.5 patients/center) between July 2015 and July 2016 (Fig. 1). There were 51.6% private centers and 45.1% public institutions, and 90% of anesthetists had more than 10 years of experience.

Among the 594 enrolled patients, 592 were included in the analysis: 309 (52.2%) received spinal anesthesia and 283 (47.8%) received general anesthesia. Both arms were comparable in terms of demographic and physical characteristics except for mean age, which was lower in the general anesthesia group compared with the spinal anesthesia group (44.0 years [range 18; 85] vs. 49.0 years [18; 93]; p = 0.0324). The study population comprised 54.4% women, median age was 47.0 years [18; 93], median weight was 72.0 kg [41; 134], and the median body mass index (BMI) was 24.8. Most patients had an ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) physical status of 1 (62.3%) (Table 1).

In both study arms, the main surgical procedures were orthopedic and urogenital (overall 43.3% and 30.7%, respectively), followed by varicose vein stripping (10.5%) and gastroenterological surgeries (7.4%). Sedative treatment, ephedrine, and other drugs were administered as premedication in 36.9%, 1.9%, and 11.3% of patients, respectively, in the spinal anesthesia arm.

Features of Spinal and General Anesthesia

A total of 36.9% of patients in the spinal anesthesia group received premedication, with benzodiazepine in 25.5% of cases. The local anesthetics used for spinal administration were prilocaine 20 mg/ml (43.8%), chloroprocaine 10 mg/ml (43.2%), and bupivacaine 5 mg/ml (12.3%) and generally in a hyperbaric solution (56.0%). The mean dose was 44.7 ± 17.4 mg (median 50.0 [7; 80]).

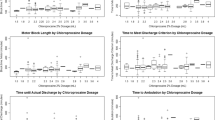

The median time between local anesthetic spinal administration and the onset of surgery was 20.0 min [4; 81]; median time to achieve complete lower limb motor block was 9.0 min [0; 32] and time to achieve T10 sensory block was 8.0 min [1; 35] (Table 2). The onset time was comparable in patients receiving chloroprocaine and prilocaine, except for the mean time to achieve a T10-level sensory block, which was significantly longer in patients who received chloroprocaine (p = 0.0097). Median times to sensory block release were 130.0 min [35; 375] for patients receiving prilocaine and 102.0 min [16; 365] for patients receiving chloroprocaine (p < 0.001). Additional analgesic treatment during the procedure was given in 26.6% cases, mostly to increase the patient’s comfort (78.0%) (Table 2). Use of general anesthesia due to failed spinal anesthesia occurred in 4.5% of patients after a median time of 31.0 min [11; 74]. Overall the success rate for spinal anesthesia was 91.6% and was comparable between the three local anesthetic agents.

General anesthesia was performed in 283 (47.8%) patients. Most patients (59.7%) received inhaled anesthesia and a laryngeal mask was used in most cases (83.2%). The median time between induction of anesthesia and the beginning of surgery was 15.0 min [1; 52] and the median delay for extubation was 60.0 min [14; 160]. Median time between anesthesia and the beginning of surgery was shorter in the general anesthesia arm compared with the spinal anesthesia arm (20.0 min [4; 81] vs. 15.0 min [1; 52]; p < 0.001) while the median duration of the procedure was comparable between the two arms (24.0 min [4; 82] vs. 25.0 min [2; 113] in the spinal and general anesthesia groups, respectively; p = 0.8053) (Table 3).

Postoperative Recovery

A total of 52.1% of patients in spinal anesthesia arm received a preventive treatment for postoperative pain and 22.7% received treatment to prevent nausea and vomiting. Both arms were comparable in terms of receiving a vasoactive agent (10.4% vs. 12.5% in the spinal and general anesthesia arms, respectively). In most cases the reason for using a vasoactive agent was hypotension (81.3% and 100%, respectively) followed by bradycardia (21.9% and 8.6% for spinal and general anesthesia, respectively).

In both arms, most patients were discharged after a postoperative spontaneous micturition (83.4% for spinal anesthesia vs. 82.9% for general anesthesia). However, the median time to postoperative spontaneous micturition was shorter in patients having general anesthesia (225.5 min [98; 560] vs. 259.0 min [109; 789]; p = 0.0011). The median time to ambulation was also significantly shorter in the general anesthesia arm (215.0 min [30; 545] vs 240.0 min [40; 1420]; p = 0.0115). In the spinal anesthesia arm, patients who received chloroprocaine had a significantly shorter median time to ambulation than those who received prilocaine or bupivacaine (196.0 min [40; 1420] vs. 255.0 min [122; 789] vs. 310.0 min [82; 622]; p < 0.001) (Table 4). In terms of the first analgesic administration, this occurred earlier in the general anesthesia arm than in the spinal anesthesia arm (55.0 min [− 115; 572] vs. 123.0 min [− 98; 475]; p < 0.001) even though in both groups it was part of the hospital protocol (in 83.1% of the cases). Overall, the median time to eligibility for discharge was 291.5 min [64; 830] and time to actual discharge was 344.0 min [135; 1772]. There were no significant differences between arms (p = 0.6698 and 0.5207, respectively) (Table 3). However, in the spinal anesthesia arm, patients who received chloroprocaine and prilocaine had a significant shorter mean time to eligibility for discharge and to actual discharge than the patients who received bupivacaine (p < 0.001) (Table 4). Most patients (92.9%) received an analgesic before discharge. Unscheduled outpatient readmission related to surgery occurred in 9/309 (3.0%) patients in the spinal anesthesia arm and in 3/283 (1.1%) patients in the general anesthesia arm.

Factors Associated with Use of the Anesthetic Technique

Factors influencing the use of the anesthetic technique are listed in Table 5. Among the 592 patients, patient’s choice seemed to be the main criterion for choosing between spinal and general anesthesia (59.7% of patients receiving spinal anesthesia and 73.0% of patients undergoing general anesthesia). The second patient criterion influencing the choice of anesthetic technique appeared to be patient’s fear of the other technique in patients scheduled for general anesthesia (30.2% versus 14.0% of patients receiving spinal anesthesia). The general anesthesia arm also considered stress/anxiety status as an important factor (24.6% vs. 14.3% in the spinal anesthesia arm). Patients in the spinal anesthesia arm considered that ease of recovery/awakening was important (26.9% vs. 5.7% in the general anesthesia arm). Both arms considered the efficacy of the anesthetic technique as quite an important factor in the choice of anesthesia (spinal anesthesia 18.1%; general anesthesia 15.6%). The surgical technique seemed to be a less important factor in determining the choice of anesthesia.

Patients’ Global Satisfaction

Out of the 594 enrolled patients, 334 (56.2%) returned the questionnaire. Pain intensity graded for the most severe pain during the 7 postoperative days was 2.0 [0.0; 10.0] in the spinal anesthesia arm and 2.5 [0.0; 10.0] in the general anesthesia arm. Over 90% of the patients were globally satisfied with their anesthesia (94.4% in the general anesthesia and 99.4% in the spinal anesthesia arms) and with the surgery (97.8% in the general anesthesia and 96.7% in the spinal anesthesia arms).

Safety

Overall, 75 patients (12.9%) experienced at least one postoperative adverse event; 45/309 (14.6%) in the spinal anesthesia arm and 30/283 (10.6%) in the general anesthesia arm. The most commonly reported postoperative adverse events were pain (in 6.3%) and hypotension (in 4.7%). Pain was more frequent in the general anesthesia arm (9.2% vs. 3.6%) and hypotension was reported only in the spinal anesthesia arm. Other adverse events were bradycardia, nausea, and vomiting (in 1.4%, 1.2%, and 0.7% of patients, respectively) and had comparable incidences in both arms.

Discussion

This study shows that some criteria, including patient’s choice, anesthetic technique and surgical technique, may influence the use between spinal and general anesthesia. Indeed, those factors identified in this observational study were mainly patient’s choice, patient’s fear of the other technique, patient’s degree of anxiety/stress, ease of recovery/awakening, and efficacy of the anesthetic technique. This study thus favors the use of spinal anesthesia with short-acting local anesthetics in ambulatory surgeries rather than the use of general anesthesia, and spinal anesthesia does not result in a significant prolongation of the hospital stay.

However, time to readiness for surgery, time to first postoperative micturition, and time to unassisted ambulation were significantly delayed in the spinal anesthesia arm compared with the general anesthesia arm, although these time differences were not practically meaningful. This is at odds with previous findings [27]. These discrepancies might be explained by different durations of the surgical procedures. Moreover, patients who had general anesthesia required postoperative analgesics sooner during postoperative care. Failure to be discharged was no more frequent in the spinal anesthesia arm. Thus, spinal anesthesia with short-acting local anesthetics may have potential advantages in ambulatory surgeries, as has been previously documented in a meta-analysis [7].

The current study compared prilocaine 20 mg/ml and chloroprocaine 10 mg/ml, which were the most frequently used local anesthetic agents. Chloroprocaine was associated with a longer onset time, a shorter block duration, and a longer time to achieve a T10 level sensory block (p = 0.0097). Recovery from motor block was faster with chloroprocaine compared to prilocaine and bupivacaine (p < 0.001). Chloroprocaine thus offered the possibility of a faster time to unassisted ambulation compared with other local anesthetic agents and a faster time to hospital discharge (p < 0.001), as has been previously reported [5, 22, 28, 29]. Prilocaine use was associated with a shorter duration of the sensory block, a shorter delay to unassisted ambulation, and shorter times to eligibility for discharge and to actual discharge compared with bupivacaine, confirming previous results [23].

Prilocaine and chloroprocaine were comparable with respect to time to surgery, time to lower-limb motor block, shift to general anesthesia, and success rates.

The overall incidence of postoperative side effects was 12.9%. As has been reported previously [30, 31], the most frequently observed side effect was pain. The first analgesic administration occurred significantly earlier in patients receiving general anesthesia, confirming that immediate recovery from spinal anesthesia is generally easier [7]. The incidences of hypotension and bradycardia observed in this study as treatment-related side effects of spinal anesthesia were similar to those reported in previous studies [29]. Incidences of nausea and vomiting were comparable in both arms.

Finally, patient satisfaction was high and satisfaction scores were comparable for both anesthetic techniques.

Study Limitations

In this protocol, patients and anesthetists could select the type of anesthesia, and patients were not randomized. Anesthetists exposed all the risks linked to the anesthesia procedure to patients during pre-anesthesia consultation. The manner in which this discussion is conducted by the anesthetists may influence patients’ perception of anesthesia. Information about the manner in which the risks were discussed should be investigated to explain reasons why the patient chose either general or spinal anesthesia.

Another point which should have been further analyzed is the patient’s or their relative’s previous experience in anesthesia. This may also contribute to initiate patients’ fear about one or another anesthesia technique. These inclusion biases could introduce discrepancies in patients’ baseline.

Although premedication may have an impact on the postoperative period, this link was not exposed in this study and should be explored in further studies. Indeed, the authors recognize that the additional anesthetics administered could potentially bias results for the time to hospital discharge.

Conclusions

Some criteria seem to influence patient and physician choice of a particular anesthesia technique in ambulatory surgery. Among the patient’s criteria, the anesthetic technique and the type of surgery may influence the choice between short-acting local anesthetics and general anesthetics. Spinal anesthesia is a valid alternative for ambulatory anesthesia, especially when using short-acting local anesthetics.

References

Lefebvre-Hoang I, Yilmaz E. Etat de lieux des pratiques de chirurgie ambulatoire en 2016. Dossiers de la DRESS. 2019;41:5–29.

Nilsson U, Jaensson M, Dahlberg K, Hugelius K. Postoperative recovery after general and regional anesthesia in patients undergoing day surgery: a mixed methods study. J Peri Anesth Nurs. 2019;34(3):517–28.

Liu SS, McDonald SB. Current issues in spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2001;94(5):888–906.

Mulroy MF. Advances in regional anesthesia for outpatients. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2002;15(6):641–5.

Camponovo C, Fanelli A, Ghisi D, Cristina D, Fanelli G. A prospective, double-blinded, randomized, clinical trial comparing the efficacy of 40 mg and 60 mg hyperbaric 2% prilocaine versus 60 mg plain 2% prilocaine for intrathecal anesthesia in ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(2):568–72.

Calderón-Ochoa F, Mesa Oliveros A, Rincón Plata G, Pinto Quiñones I. Effectiveness and safety of exclusive spinal anesthesia with bupivacaine versus femoral sciatic block during the postoperative period of patients having undergone knee arthroscopy: systematic review. Colom J Anesthesiol. 2019;47(1):57–68.

Liu SS, Strodtbeck WM, Richman JM, Wu CL. A comparison of regional versus general anesthesia for ambulatory anesthesia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(6):1634–42.

Capdevila X, Dadure C. Perioperative management for 1 day hospital admission: regional anesthesia is better than general anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2004;55(Suppl):33–6.

Pourel E, Lambert M, Mekler G, et al. Anesthésie LocoRegionale en Ambulatoire. In: Conférences d'Actualisation Elsevier Ed, 2008. pp 61–75.

Parker MJ, Handoll HH, Griffiths R. Anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:521.

Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Mendoza-Lattes S, Callaghan JJ. Differences in short-term complications between spinal and general anesthesia for primary total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2013;95(3):193–9.

Bessa SS, Katri KM, Abdel-Salam WN, El-Kayal E-SA, Tawfik TA. Spinal versus general anesthesia for day-case laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22(6):550–5.

Fernández-Ordóñez M, Tenías JM, Picazo-Yeste J. Spinal anesthesia versus general anesthesia in the surgical treatment of inguinal hernia. Cost-effectiveness analysis. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2014;61(5):254–61.

Morris MT, et al. An analysis of the cost-effectiveness of spinal versus general anesthesia for lumbar spine surgery in various hospital settings. Global Spine J. 2019;9(4):368–74.

Lennox PH, Vaghadia H, Henderson C, Martin L, Mitchell GWE. Small-dose selective spinal anesthesia for short-duration outpatient laparoscopy: recovery characteristics compared with desflurane anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 2002;94(2):346–50.

Schneider M, et al. Transient neurologic toxicity after hyperbaric subarachnoid anesthesia with 5% lidocaine. Anesth Analg. 1993;76(5):1154–7.

Tarkkila P, Huhtala J, Tuominen M. Transient radicular irritation after spinal anaesthesia with hyperbaric 5% lignocaine. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74(3):328–9.

Freedman JM, Li D-K, Drasner K, Jaskela MC, Larsen B, Wi S. Transient neurologic symptoms after spinal anesthesia: an epidemiologic study of 1863 patients. Anesthesiology. 1998;89(3):633–41.

Pollock JE, Mulroy MF, Bent E, Polissar NL. A comparison of two regional anesthetic techniques for outpatient knee arthroscopy. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(2):397–401.

Hampl KF, Schneider MC, Pargger H, Gut J, Drewe J, Drasner K. A similar incidence of transient neurologic symptoms after spinal anesthesia with 2% and 5% lidocaine. Anesth Analg. 1996;83(5):1051–4.

Camponovo C, et al. Intrathecal 1% 2-chloroprocaine vs. 0.5% bupivacaine in ambulatory surgery: a prospective, observer-blinded, randomised, controlled trial: Spinal chloroprocaine vs. bupivacaine. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(5):560–6.

Lacasse M-A, et al. Comparison of bupivacaine and 2-chloroprocaine for spinal anesthesia for outpatient surgery: a double-blind randomized trial. Can J Anesth. 2011;58(4):384–91.

Black AS, Newcombe GN, Plummer JL, McLeod DH, Martin DK. Spinal anaesthesia for ambulatory arthroscopic surgery of the knee: a comparison of low-dose prilocaine and fentanyl with bupivacaine and fentanyl. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(2):183–8.

Guntz E, Latrech B, Tsiberidis C, Gouwy J, Kapessidou Y. ED50 and ED90 of intrathecal hyperbaric 2% prilocaine in ambulatory knee arthroscopy. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61(9):801–7.

Matthey PW, Finegan BA, Finucane BT. The public’s fears about and perceptions of regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(2):96–101.

Oldman M, et al. A survey of orthopedic surgeons’ attitudes and knowledge regarding regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(5):1486–90.

Park YB, Chae WS, Park SH, Yu JS, Lee SG, Yim SJ. Comparison of short-term complications of general and spinal anesthesia for primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2017;29(2):96–103.

Boublik J, Gupta R, Bhar S, Atchabahian A. Prilocaine spinal anesthesia for ambulatory surgery: a review of the available studies. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2016;35(6):417–21.

Teunkens A, Vermeulen K, Van Gerven E, Fieuws S, Van de Velde M, Rex S. Comparison of 2-chloroprocaine, bupivacaine, and lidocaine for spinal anesthesia in patients undergoing knee arthroscopy in an outpatient setting: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41(5):576–83.

Ghosh S, Sallam S. Patient satisfaction and postoperative demands on hospital and community services after day surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81(11):1635–8.

Chung F, Un V, Su J. Postoperative symptoms 24 h after ambulatory anaesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 1996;43(11):1121–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eric Leutenegger (Gecem, Montrouge, France) for the operational coordination of the study and all the study investigators.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee and Open Access fees were funded by Nordic Pharma.

Medical Writing Assistance

Nathalie Lee of KPL provided medical writing assistance. This assistance was funded by Nordic Pharma.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

XC and FB wrote this manuscript, which was closely reviewed by PZ and LD. LD, XC, FB, HB, CA, PZ, LJ, OC and HH-D designed the study, performed the investigation, and analyzed the data.

Disclosures

Francis Bonnet is consultant for Nordic Pharma, Grünenthal, The Medicines Company and Ambu. Xavier Capdevila is consultant for Nordic Pharma and Grünenthal. Christophe Aveline is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Laurent Delaunay is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Hervé Bouaziz is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Paul Zetlaoui is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Olivier Choquet is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Laurent Jouffroy is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. At the time of the study Laurent Jouffroy was an employee of Clinique des Diaconesses, Strasbourg, France and is now employee of Clinique Rhéna, Strasbourg, France. Hélène Herman-Demars is an employee of Nordic Pharma.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was approved by the Sud-mediterranée IV (Hôpital Saint Eloi, Montpellier, France) Ethics Committee on June 23, 2015 and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02529501). Every patient gave oral consent after receiving full oral and written information about their data collection and the use of their personal information.

Data Availability

The data are available on request from GECEM, Montrouge, France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11210276.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Capdevila, X., Aveline, C., Delaunay, L. et al. Factors Determining the Choice of Spinal Versus General Anesthesia in Patients Undergoing Ambulatory Surgery: Results of a Multicenter Observational Study. Adv Ther 37, 527–540 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01171-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01171-6