Abstract

Introduction

Exenatide once weekly (ExeOW, Bydureon®, Astra Zeneca), a drug belonging to the class of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, is the first agent approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D) that can be administered on a weekly basis.

Methods

Data concerning treatment of T2D with ExeOW are reviewed with special reference to its long-term efficacy, tolerability, and safety. Relevant literature was identified through the PubMed database from inception to January 2015.

Results

In randomized clinical trials ExeOW, as add-on to oral antidiabetics, achieved significantly improved glycemic control compared to maximum recommended doses of exenatide twice daily, sitagliptin, pioglitazone, and insulin glargine, as measured by HbA1c. In drug-naïve patients ExeOW was superior to sitagliptin and non-inferior to metformin, whereas non-inferiority to pioglitazone and liraglutide was not proven. In different trials reductions in HbA1c ranged from −1.1% to −2.0%. ExeOW therapy over 6 months was also associated with a mean weight loss of −2 to −4 kg, improved systolic blood pressure and lipid profile, and no hypoglycemia unless associated to sulfonylurea. ExeOW long-term therapy up to 3–6 years allowed persistent glycemic control (HbA1c −1.6%), sustained decreases in blood pressure (−2 mmHg), and improvements of lipid profile. ExeOW tolerability was comparable to that of the other GLP-1 receptor agonists, with better gastrointestinal tolerability when direct comparison was done (namely liraglutide and exenatide BID), but higher incidence of injection site reactions and few treatment discontinuations mainly due to gastrointestinal events.

Conclusion

ExeOW is a well-tolerated and convenient option for long-term treatment of T2D allowing significant and persistent glycemic control with moderate weight loss and low risk of hypoglycemia unless associated with sulfonylureas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a 30-amino acid peptide hormone produced by the intestinal epithelial endocrine L cells through differential processing of proglucagon. It is secreted in response to a meal and plays an important role in glycemic control by acting on multiple organs and metabolic pathways. GLP-1 is responsible for 50–70% of the total postprandial insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner [1]; its action on the pancreatic endocrine system also includes stimulation of insulin biosynthesis, reduction of glucagon secretion, modulation of insulin sensitivity of beta cells and, at least in animal models, a positive action on beta cell mass itself [2]. Once secreted, GLP-1 is degraded within minutes.

The short in vivo half-life of GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) has historically represented a significant barrier to their routine clinical use, driving the search for new agents/formulations with more potent and longer-lasting activity. ExeOW is an extended release formulation of exenatide. Exenatide twice daily (ExeBID, Byetta®, Astra Zeneca) was the first GLP-1 receptor agonist approved for management of T2D. ExeOW requires only a once-weekly injection as compared to twice-daily injections of the ExeBID formulation. We reviewed data concerning treatment of T2D with ExeOW with special reference to its long-term efficacy, tolerability, and safety.

Methods

Studies for this review were identified through PubMed database searches (titles and abstracts) from inception until January 2015; search terms included GLP-1 receptor agonist, exenatide, slow release, long acting, once week, once-weekly, QW, OW—and other terms that could have been related to individual sections of this review. Neither language restriction nor a priori specific inclusion or exclusion criteria were used to filter the literature search except for selecting human studies only. Additional references were identified manually either from references listed in the studies selected through PubMed or from abstracts presented at 2014 American Diabetes Association (ADA) and European Association of the Studies of Diabetes (EASD) conferences. All review articles were considered while for clinical trials only studies lasting more than 3 months that included ExeOW as test drug or comparator were considered. Overall 90 papers were retrieved and eight were discarded.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Indication and Use

ExeOW was initially approved in the European Union in 2011 for the treatment of T2D in combination with metformin, sulfonylurea, and thiazolidinedione when these do not provide adequate glycemic control. In the USA, ExeOW received FDA approval in 2012 for use in patients with T2D as an adjunct to diet and exercise. ExeOW is currently not approved for use in combination with basal insulin.

Formulation and Pharmacokinetics

Exenatide in its original subcutaneous formulation reaches its mean peak concentration within 2 h and has a terminal half-life of 2.4 h requiring twice-daily administration [3].

ExeOW has been developed by adopting an encapsulation technique that slows the release of exenatide, allowing a once-weekly subcutaneous administration. The product is to be reconstituted just before injection. The pharmacokinetics of ExeOW have been assessed in one single-dose and two multiple-dose studies in patients with T2D [4]. It is characterized by a multiphasic concentration–time profile due to the slow release of the drug in the bloodstream through the progressive dissolution of the polymeric matrix of the microspheres encapsulating exenatide [5]. The process occurs in three stages: initial phase, diffusion, and final erosion release [5]. Once injected, the microsphere hydrates and tends to form amalgams, initially releasing the drug molecules located on the surface or closer to the surface of the matrix. During the diffusion phase, the drug is released at a constant rate into the bloodstream, and finally during the erosion phase the matrix is completely dissolved. Consistent with this model of release, the initial time to maximum concentration after a single dose ExeOW is 2.1–5.1 h, and two subsequent phases of drug release follow several weeks later. After administration of the recommended dose of 2 mg, ExeOW minimal effective concentrations of greater than 50 pg/mL are attained in approximately 2 weeks and steady-state concentrations of approximately 300 pg/mL within 6–7 weeks [6]. After treatment discontinuation, detectable blood levels of the drug are present for approximately 10 weeks [5]. Nonclinical studies have shown that exenatide is predominantly eliminated by glomerular filtration with subsequent proteolytic degradation.

ExeOW is commercially available in two delivery forms, namely a single-dose tray (BYDUREON®) and a single-dose, single-use, prefilled, dual-chamber pen that can be twisted for reconstitution and priming (BYDUREON Pen®) and supports ease of administration by patients and caregivers. This device has been positively evaluated by untrained and trained health care practitioners and patients; clinical studies confirm that it is easy for patients to learn how to use the dual-chamber pen [7].

Antibody Formation

Similarly to ExeBID, ExeOW stimulates an immunogenic response with formation of antibodies which rarely achieve high titers, generally tend to decrease over time, and do not significantly alter drug activity or safety in most patients [4, 8, 9].

A review of clinical trials comparing ExeOW versus ExeBID showed that low titers of anti-exenatide antibodies are common with both formulations (32% ExeBID, 45% ExeOW), but without manifest effects on drug efficacy, whereas higher titers of antibodies are less common (5% ExeBID, 12% ExeOW) and may be associated with an attenuated glycemic control [10]. Anti-exenatide antibodies did not impact the safety of exenatide except for injection site reactions, which were more frequent in antibody-positive as compared to antibody-negative patients [10].

Clinical effects

Dose-finding studies [4, 6, 9] have established 2 mg per week as the optimal dose for ExeOW in T2D patients: after 15 weeks of therapy 2 mg ExeOW achieved a superior glycemic control as compared to placebo or a lower dose of 0.8 mg/week, inducing an average reduction of HbA1c levels from baseline of 1.7%, with 86% of patients attaining HbA1c levels below the therapeutic target of 7%. A drop in HBA1c [4] and also in fasting glucose levels was already attained at 3 weeks [4, 9]. In addition, while placebo and the lower ExeOW dose tested had no effect on body weight, the 2 mg per week dosage induced a significant weight reduction (−3.8 ± 1.4 kg). This dosage has been therefore further evaluated within randomized clinical trials (RCT) aimed at determining the activity and safety of ExeOW in T2D patients suboptimally controlled with other antidiabetic therapies. RCTs conducted with ExeOW are summarized in Table 1.

A cluster of studies named DURATION (Diabetes therapy Utilization: Researching changes in A1C, weight and other factors Through Intervention with exenatide ONce weekly) evaluated the efficacy and safety of ExeOW when administered in patients with T2D either as monotherapy in adjunct to diet and exercise [11] or as an add-on to oral antidiabetic agents including metformin alone [12] or in combination with sulfonylurea and/or thiazolidinedione and sodium glucose transporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2-I) dapagliflozin [8, 13,14,15,16].

Two studies compared ExeOW to ExeBID [8, 14]. Further studies evaluated ExeOW versus the oral DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin, pioglitazone [11, 12], metformin [11], basal insulin glargine (GLAR) [13], or a GLP-1 analogue for daily use, liraglutide [15]. All of these studies had HbA1c mean decrease from baseline as primary endpoint.

While in most of these studies therapy lasted for 24–30 weeks, additional important long-term efficacy and safety data can be drawn from the non-comparative extensions of the DURATION-1 trial (up to 6 years) [17] and the comparative 3-year extension of the DURATION-3 trial [18].

ExeOW has been tested in Asian populations, in which it showed efficacious glucose and weight control; safety and tolerability were consistent with observations in non-Asian patients [19]. T2DM in Asian patients is characterized by beta cell dysfunction rather than insulin resistance [20, 21].

Effects on Glycemic Control

ExeOW as Monotherapy

Only one RCT has assessed the efficacy of ExeOW when used as monotherapy (DURATION-4 [11]). This RCT was designed to prove non-inferiority in comparison with metformin, pioglitazone, and sitagliptin in T2D uncontrolled by diet and physical activity. The patients were exenatide naïve and were followed for 26 weeks. As shown in Table 1, ExeOW attained a glycemic control that was significantly superior to that achieved with the DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin and non-inferior to that achieved with metformin. In contrast with results obtained in a previous study [12] where ExeOW proved to be more effective than pioglitazone as an add-on to metformin, criteria for non-inferiority versus pioglitazone monotherapy were not met. The authors hypothesized that different baseline characteristics of the patient populations, such as the mean duration of diabetes, could have been confounding factors contributing to such a result.

ExeOW as Add-on to Other Antidiabetic Therapies

ExeOW Compared to ExeBID

Two studies compared ExeOW to ExeBID testing the single-dose tray [8, 14].

The DURATION-1 study [8] was designed to test non-inferiority of ExeOW as compared to ExeBID in patients receiving metformin, sulfonylurea, or thiazolidinedione monotherapy or in combination, based on the difference in the reduction of HbA1c (95% CI upper limit of the difference <0.4%). Treatment within the initial randomized portion of the study had a duration of 30 weeks but subsequent cohorts of patients entered long-term uncontrolled extensions of the study up to 7 years: data up to 6 years have been published to date [17].

At week 30 ExeOW attained superior glycemic control as compared to ExeBID in terms of mean HbA1C decrease (−1.9 vs −1.5%, p = 0.0023), proportion of patients attaining HbA1c <7% (77% vs 61%) or <6.5% (49% vs 25%), and mean FBG decrease (−2.3 vs −1.4 mmol/L, p < 0.0001) (Table 1). At 1-year follow-up [22], while patients initially treated with ExeOW maintained results obtained at week 30, those switched from ExeBID further improved glycemic control similarly to the group treated with ExeOW upfront (Table 1).

At 3 years, antidiabetic therapy was unchanged in 83% of patients and glycemic control was generally maintained: 55% and 33% of patients had HbA1c levels <7% or ≤6.5%, respectively [23].

The slight progressive trend upward in HbA1c and FPG levels and the reduced proportion of patients attaining HbA1c below target levels noted after the first year of ExeOW treatment [23] were probably due to the natural progression of the disease. This interpretation is corroborated by findings from another RCT (DURATION-3) in which, around week 84 of therapy, a similar rise in HbA1c levels was observed both in patients treated with ExeOW and in those receiving GLAR [24].

Recently, 6-year follow-up data have been reported from 136 patients, 53% of those who entered in the open-ended assessment period of the DURATION-1 study [17]. Prolonged treatment with ExeOW allowed a persistent and meaningful long-term glycemic control with reduction in HbA1c levels from baseline similar to that achieved at previous follow-ups (Table 1).

The superiority of ExeOW over ExeBID has been also confirmed in a twin RCT conducted in the USA in the same target population patients [14] (Table 1).

ExeOW Compared to Pioglitazone and Sitagliptin

ExeOW has been demonstrated to be more effective than pioglitazone and the oral DPP-4 sitagliptin as add-on treatment to metformin in a 26-week RCT testing the superiority of ExeOW in terms of HbA1c change from baseline [12]. ExeOW induced a significantly greater reduction in HbA1c from baseline as compared to both pioglitazone and sitagliptin. FPG mean decrease was also more pronounced with ExeOW, reaching statistical significance when compared to sitagliptin (Table 1).

Efficacy of ExeOW associated with thiazolidinedione (rosiglitazone or pioglitazone) has also been tested in a non-comparative trial primarily designed to assess ExeOW tolerability and safety in 134 subjects (44 exenatide naïve and 90 switched from ExeBID); metformin background therapy was allowed [25]. Mean decrease in ExeOW-naïve patients was −0.7%, while patients switching from ExeBID to ExeOW achieved a further improvement of −0.4%.

ExeOW Compared to Insulin

Treatment with ExeOW has been compared to GLAR in a randomized, superiority study conducted in patients with suboptimal glycemic control with oral antidiabetic drugs [13]. GLAR was titrated, starting from an initial dose of 10 IU, to achieve an FPG between 4 and 4.5 mmol/L. During the initial 26-week portion of the study, the change in HbA1c was significantly greater in patients taking ExeOW than in those treated with GLAR and, significantly, more patients treated with ExeOW achieved HbA1c targets of 7%. As expected, GLAR produced significantly greater reductions in FPG than ExeOW, while ExeOW produced significantly greater reductions in postprandial glucose excursions than GLAR (p = 0.001 after morning meals and p = 0.033 after evening meals).

Three-year follow-up data from this study [18] confirm the sustained long-term activity of ExeOW. Throughout the 3-year treatment period, mean HbA1c was lower in patients given ExeOW than in those given GLAR; at 3 years the mean decrease from baseline in HbA1c was still significantly greater in patients treated with ExeOW and more patients treated with ExeOW achieved HbA1c targets (Table 1). Monitoring of FPG confirmed lower concentrations throughout the study in patients given GLAR, with significantly greater reductions at 3 years.

Randomized data are also available showing superiority of treatment with ExeOW over DET in patients with suboptimal glycemic control with metformin with or without sulfonylurea [26] (Table 1). DET was administered once or twice daily and titrated to achieve an FPG of 5.5 mmol/L. This study used a composite primary endpoint, i.e., percentage of patients achieving a target HbA1c of ≤7.0% showing a decrease of ≥1 kg in body weight. A 6-month treatment with ExeOW resulted in a greater proportion of patients achieving the target in comparison with DET (44.1% vs. 11.04%, p < 0.0001).

Whereas treatment with long-acting basal insulin analogue acts predominantly on fasting blood glucose, GLP-1 agonists—including ExeOW—also have an important action on both fasting and postprandial blood glucose [4, 8, 9]. Vora and colleagues [27] recently analyzed results from three RCT comparing ExeOW versus GLAR (two studies) or DET (one study) in terms of effects on fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels considering different indexes of daily glycemic variability including mean amplitude of glucose excursions (MAGE), blood glucose range and variability. While confirming the superior activity of ExeOW in reducing HbA1c, this analysis indicated that ExeOW reduces blood glucose variability and postprandial glucose levels as compared to GLAR (p < 0.001) and DET (p = NS).

ExeOW Compared to Liraglutide

Non-inferiority of ExeOW as compared to the once-daily GLP-1 analogue liraglutide 1.8 mg (LIRA) was tested in a large RCT which used more stringent criteria for non-inferiority than those used in prior non-inferiority studies (upper bound of the 95% CI of the difference in change of HbA1c <0.25% as compared to 0.4% in other ExeOW non-inferiority studies) [15]. Both once-daily liraglutide and once-weekly exenatide led to improvements in glycemic control, with greater reductions noted with liraglutide. Change in HbA1c at endpoint was significantly greater in LIRA than in ExeOW groups, −1.48% vs.−1.28%, p = 0.02) with the treatment difference (0.21%, 95% CI 0.08–0.33) not meeting predefined non-inferiority criteria.

Scott and colleagues performed a network meta-analysis of 22 RCT conducted with ExeOW or liraglutide (1.2, 1.8 mg) aimed at evaluating their relative efficacy in lowering HbA1c: estimation of mean differences in HbA1c relative to placebo or each other and probability rankings identified no meaningful differences, suggesting similar glycemic control [28].

ExeOW in Combination with Dapagliflozin

GLP-1RA and SGLT2-I agents reduce hyperglycemia, weight, and improve cardiovascular risk factors by complementary mechanisms. DURATION-8 is the first phase III study of a GLP-1RA (ExeOW) and SGLT2-I (dapagliflozin, DAPA) combination in T2D patients. After 28 weeks, the change in baseline HbA1c was −2.0% (95% CI −2.1 to −1.8) in the ExeOW plus DAPA group, −1.6% (−1.8 to −1.4) in the ExeOW group, and −1.4% (−1.6 to −1.2) in the DAPA group. ExeOW plus DAPA significantly reduced HbA1c from baseline to week 28 compared with ExeOW alone (−0.4% [95% CI −0.6 to −0.1]; p = 0.004) or DAPA alone (−0.6% [−0.8 to −0.3]; p < 0.001) [16].

Non-Glycemic Effects

Effects on Body Weight

Both exenatide formulations, ExeBID and ExeOW, were demonstrated to be negative regulators of appetite and food intake, and these effects result in an appreciable body weight reduction [8, 29]. The underlying mechanism is complex and is the result of combined actions on different systems including the gastrointestinal and the central nervous systems (CNS) [30]. The gastrointestinal effects of GLP-1 and its agonists, including exenatide, are mediated by inhibition of gastrointestinal motility and secretion [31]. They are involved in the “ileal brake” mechanism causing slowdown of progression of food in the gastrointestinal tract with consequent lowering of postprandial blood glucose levels and increased sense of satiety. However, the effects on the gastrointestinal system do not appear to be the main mechanism responsible for body weight decrease during ExeOW therapy. In animal models GLP-1 receptors have been found in different regions of the brain, with high density in areas implicated in the regulation of food intake [32]. Exenatide is able to cross the blood–brain barrier when administered peripherally [33] and, therefore, can act directly on the CNS. It also exerts an indirect action by activating GLP-1 receptors expressed on vagal afferents [34].

In all RCTs, treatment with ExeOW consistently reduced body weight (Fig. 1), except for one small dose-finding study conducted in Japanese patients where a neutral effect on weight was observed, possibly as a result of leanness [35] of the Japanese patients enrolled in this study (30 subjects, mean BMI around 26 kg/m2).

ExeOW-induced weight loss was dose dependent [4], durable, and consistent over time [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. After 6 months of therapy, mean body weight decrease ranged from -2.0 kg [10] to −3.7 kg [8] and was significantly more marked than with pioglitazone and sitagliptin [12] while, as expected, GLAR [13, 18] induced a significant body weight increase (Table 3). After 5 and 6 years of ExeOW treatment, the reduction in body weight was 3 and 4.2 kg, respectively [17, 36] (Fig. 1).

A pooled analysis from eight studies indicates that ExeOW improves glycemic control independent of weight change but the magnitude of improvement increases with increasing weight loss [35].

Effects on Cardiovascular System

In the diabetic population, GLP-1 agonists, including exenatide, have different and peculiar effects on the cardiovascular system, including modification of cardiovascular risk factors, hemodynamic effects on cardiac function, and cardioprotective effects [37]. The effects of exenatide on the cardiovascular system were evaluated in both preclinical models and in clinical trials. A summary of available evidence is provided below.

Changes of Biochemical Indicators of Cardiovascular Risk

The effect of ExeOW on the lipid profile has been extensively studied in five RCTs and their long-term extensions, when applicable. Chiquette and colleagues found that treatment with ExeOW modifies the lipoprotein pattern, reducing apolipoprotein B and ApoB/ApoA ratio [38].

A positive effect on the lipid profile has been demonstrated with ExeOW after 6-month or 1-year treatment in two RCT versus ExeBID [8, 11, 17, 22] which had been previously demonstrated to induce a significant improvement of triglycerides, HDL-C, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels (p < 0.005 for all parameters) as compared to glimepiride in patients receiving metformin [39]. Exe-LAR induced a decrease in plasma triglycerides up to 15% at 1-year, a slight decrease in total cholesterol, and a slight increase in HDL levels [8] (Table 2). These positive effects persisted for up to 6 years [17] (Table 2). The effect of ExeOW on the lipid profile was comparable to that of LIRA in an RCT [15].

Hemodynamic Effects

A positive effect of ExeOW on systolic blood pressure (SBP) has been documented across several RCTs (Table 2): a statistically significant decrease in SBP was demonstrated as compared to sitagliptin [12], GLAR [16, 18], and DET [26]. Equivocal results were instead reported regarding diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values (Table 2), with statistically significant results reported at 3-year follow-up in a single study [18]. A meta-analysis which considered 12 RCTs conducted with GLP-1 receptor agonists reported a consistent reduction in SBP in comparison with controls [40].

A positive, although small, chronotropic effect (2–4 bpm) was observed consistently in different studies conducted with ExeOW [11, 17]. The relationship between the observed changes in blood pressure and heart rate have not yet been clarified; more data are required to draw conclusions as regards the impact of these hemodynamic effects in terms of cardiac outcomes [41].

Finally, studies to evaluate the effects of treatment with exenatide on prolongation of QTc interval have been conducted only using ExeBID: no appreciable effect has been demonstrated [42,43,44].

Cardioprotective Effects

Activation of the GLP-1 receptor exerts, at least in vitro, a protective function on cardiomyocytes by increasing glucose uptake and acting on the metabolic pathways of oxidative stress and apoptosis [45]; in addition, preclinical studies suggest that GLP-1 receptors located in the heart and vasculature may play a protective role with respect to cardiovascular disease [46, 47].

The possible use of exenatide in interventional cardiology has been investigated. In a porcine model experimental exenatide reduced ischemic injury in terms of size and deterioration of cardiac function [48]. In a clinical study involving patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction, intravenous infusion of low-dose exenatide during reperfusion and for the following 6 h induced a 30% reduction of the myocardial infarct area at 3 months in the subset of patients with shorter lag between the first medical contact and the first inserted balloon [49].

Further supporting evidence can be derived from a prospective placebo-controlled RCT assessing the safety and feasibility of high-dose exenatide in patients with a first ST elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: administration of high doses of exenatide was safe and feasible with a trend towards a smaller infarct size at 4 months as a percentage of the area at risk in patients with thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 0 or 1 flow receiving exenatide [50].

A large randomized, placebo-controlled study (EXSCEL) is currently ongoing in patients with T2D to assess the impact of ExeOW as add-on to usual care on major cardiovascular outcomes as measured by a composite endpoint of cardiovascular-related death, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or nonfatal stroke; the study will recruit 14,000 patients and relevant results are expected in 2018 [51].

Tolerability

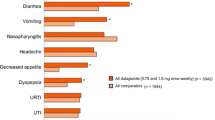

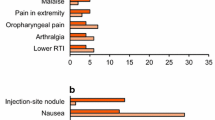

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events reported in RCTs with ExeOW are summarized in Table 4. The most frequent events associated with ExeOW therapy are gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) and injection site reactions (nodules, pruritus, erythema). These events occur more frequently in the initial phase of treatment, with incidence decreasing over time as indicated by the analysis of the proportion of patients reporting selected symptoms over time [15, 18], and further confirmed by the analysis of the annual event rates over a 6-year follow-up within the DURATION-1 study [17] (Table 5). The overall withdrawal rate in RCTs ranged from 6.3% to 25.3%, with 2.4% to 11% of patients discontinuing treatment because of an adverse event, mainly due to gastrointestinal side effects (Table 3).

Gastrointestinal side effects and withdrawals due to adverse events reported with ExeOW, though generally more frequent as compared to oral antidiabetic agents or insulin, were markedly lower than with ExeBID [52] or with LIRA (Table 4). Though reactions at the injection site were more frequent with ExeOW, pruritus and erythema decreased significantly over time; injection site nodules, infrequent during the initial phase, were not reported during long-term treatment [17] (Table 5).

Hypoglycemia

Major hypoglycemia has not been observed in association with ExeOW therapy. At the recommended dosage, minor (defined as plasma glucose concentration <3 mmol/L), symptomatic hypoglycemia has been reported in 1–11% of patients (Table 4). Its frequency and severity are higher when ExeOW is associated with sulfonylurea [53].

Safety

Over the past years there have been concerns for the long-term safety of incretin-based therapies, specifically as regards their potential to promote rare events such as acute pancreatitis, to initiate histological changes suggesting chronic pancreatitis, including associated preneoplastic lesions, and in the long run even pancreatic cancer. Concerns were also raised as regards a potential increased risk of developing medullary thyroid cancer [54]. Available data from preclinical and clinical studies are conflicting and no causal relationship has been proven to date between incretin-based therapies, including ExeOW, and an increased risk for any of these pathologies.

The possible association between incretin-based therapies, including ExeOW, and an increased risk of acute pancreatitis has been suggested on the basis of a limited number of postmarketing surveillance reports, which led to limitations in their use in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Findings from animal studies have been inconsistent [55, 56]. In addition, clinical evidence is available suggesting that patients with T2D may have an increased risk of acute pancreatitis and biliary disease [57].

Meta-analyses and observational studies assessing the risk of acute pancreatitis during incretin-based therapy indicate an odds ratio (OR) ranging from 0.90 to 0.95 [58,59,60]. In a meta-analysis of 10 RCTs and three retrospective cohort studies conducted with exenatide the OR for exenatide was 0.84 (95% CI 0.58–1.22) [61]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 55 randomized and five observational studies [62] including 353,639 patients receiving incretin-based therapies indicated that the overall incidence of pancreatitis is low (0.11% in RCTs and 0.47% in cohort studies) and that these drugs do not increase the risk of pancreatitis (overall OR in randomized trials of 1.11, 95% CI 0.57–2.17 and OR in observational studies ranging from 0.9 to 1). In particular, the analyses conducted on the two cohort studies involving more than 20,000 patients receiving exenatide showed no increased risk of pancreatitis [62], the adjusted OR in two observational studies being 0.93, 95% CI 0.63–1.36 in one study [58, 59] and 0.9, 95% CI 0.6–1.5 in the other [60].

A potentially increased risk of pancreatic cancer has been also suggested in patients treated with exenatide or sitagliptin on the basis of data from the German and FDA adverse event regulatory databases [54, 63]. Data from RCTs do not indicate an increased risk for pancreatic cancer with these medicines, and this risk has not been specifically assessed in observational studies or meta-analyses, thus no firm conclusion can be drawn in this regards [64].

In the summer of 2013 The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) finalized a review of GLP-1-based diabetes therapies and concluded that available data do not support the concerns of increased risk of pancreatic adverse events with the use of this class of drugs [65]. However, concerns in this regard have not ceased and continue to fuel the international debate [54, 66, 67] and studies to further explore potential risks involving pancreas.

In the meantime it is recommended to educate patients to recognize the symptoms of pancreatitis and to stop taking the medication if these occur. If the workup confirms the diagnosis of pancreatitis, treatment with ExeOW should not be resumed.

The observation of an increased incidence of C cell thyroid carcinoma in rats treated with GLP-1 agonists, including ExeOW, has raised concerns about the possible induction of such neoplasms in humans; actually in the USA (but not in Europe) ExeOW, similarly to all the other GLP-1 agonists, is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma and in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. The human relevance of the thyroid alterations observed in rodents has been questioned as in this species these alterations may spontaneously occur and medullary carcinomas can also be induced with placebo [68]. Available clinical evidence does not allow definite conclusions in this regard to be drawn. While in RCTs there has been no signal for an excess prevalence of thyroid neoplasms with GLP-1 agonists, data from the FDA adverse event reporting system indicate an excess of reported thyroid cancers with both exenatide and liraglutide [54]. As these data cannot be considered fully reliable because of lack of control and possible increased reporting triggered by media attention, an active surveillance program for cases of medullary thyroid carcinoma has been implemented in the USA to monitor the annual number and to establish a registry for new cases occurring in patients receiving GLP-1 analogues, including ExeOW [69].

Patient Acceptance

Patient satisfaction is an important variable for the acceptance and ultimately for the efficacy of antidiabetic therapies.

In a survey aimed at assessing patients’ attitudes toward a once-weekly injectable therapy in patients with chronic illnesses, glucose-lowering medications administered on a weekly basis were viewed positively by patients with T2D, especially those already treated with injections or dissatisfied with their current treatments or outcomes [70].

Patient-related outcomes were prospectively evaluated in one open label RCT comparing ExeOW versus ExeBID [8, 71] and in one double-blind RCT comparing ExeOW versus PIO and SITA [12, 72]. Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire–status (DTSQ-s) and Impact of Weight on Quality of Life Lite (IWQOL-Lite) were assessed in both studies, over 6-month up to 1-year treatment duration. Within the DURATION-1 study patients in both groups experienced significant and clinically meaningful improvements in treatment satisfaction and QoL which further significantly improved between weeks 30 and 52 for patients switching from ExeBID to ExeOW [8]. In the DURATION-2 study, the patient-related outcome advantages of ExeOW over SITA and PIO were most notable for the measures of IWQOL-Lite while fewer differences were registered for the more generic QoL measures [12, 72].

A general willingness to continue ExeOW therapy, despite the need for injections, was reported in relation to the improved flexibility and convenience. The side effects, gastrointestinal and injection site-related, did not affect the treatment satisfaction and adherence to therapy [72].

A retrospective study using prescription claims data from US patients recently evidenced that GLP-1 receptor agonist-naïve patients were significantly more prone to adhere to a weekly based treatment with ExeOW compared to once-daily LIRA or twice-daily ExeBID [73].

Positioning of ExeOW in Management of T2D

Early intervention and a personalized stepwise approach are recommended by international guidelines to ensure success in the management of T2D [74, 75]. Changes in lifestyle and metformin are seen as first-line option; further therapy includes two or more drug combinations. In these algorithms, GLP-1 receptor agonists as monotherapy have a place when metformin is not tolerated or as add-on to metformin if a more marked effect on weight loss and/or a lower risk of hypoglycemia is desirable.

Insulin has been considered for years the best and only option for reducing blood glucose levels when HbA1c is above 9% on oral combinations. Available data indicate that ExeOW is a valid alternative to insulinization, irrespective of HbA1c baseline levels, on the basis of a comparable clinical efficacy versus GLAR [74, 76, 77]. Combinations of insulin with incretin agents have been explored in RCTs and retrospective studies suggesting that they may offer potential practical advantages including significant A1c lowering and beneficial effects on body weight [78, 79]. Currently exenatide LAR is not indicated for use in combination with a basal insulin: an RCT is ongoing to evaluate the potential advantages of this combination [80].

Conclusion

The recent availability of new classes of medications and drug formulations represents an important improvement in the treatment of T2D. The positioning of GLP-1 receptor agonists has been recently revisited and as such they are regarded not only as appropriate add-on therapy to metformin but also as a valid alternative to basal insulin, even when HbA1c levels are elevated.

Available long-term data, the longest ever reported, clearly indicate that ExeOW treatment can result in a sustained glycemic control and durable weight loss offering long-lasting efficacy associated with modest side effects and not burdened by hypoglycemia or other major unforeseen adverse events in patients choosing to continue on therapy.

Treatment with ExeOW is associated with greater patient satisfaction and improved quality of life, potentially favoring greater patient adherence to therapy.

References

Nauck MA, Homberger E, Siegel EG, et al. Incretin effects of increasing glucose loads in man calculated from venous insulin and C-peptide responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63(2):492–8.

Wick A, Newlin K. Incretin-based therapies: therapeutic rationale and pharmacological promise for type 2 diabetes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(Suppl 1):623–30.

Nielsen LL, Young AA, Parkes DG. Pharmacology of exenatide (synthetic exendin-4): a potential therapeutic for improved glycemic control of type 2 diabetes. Regul Pept. 2004;117(2):77–88.

Kim D, MacConell L, Zhuang D, et al. Effects of once-weekly dosing of a long-acting release formulation of exenatide on glucose control and body weight in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1487–93.

DeYoung MB, MacConell L, Sarin V, Trautmann M, Herbert P. Encapsulation of exenatide in poly-(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres produced an investigational long-acting once-weekly formulation for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(11):1145–54.

Fineman M, Flanagan S, Taylor K, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of exenatide extended-release after single and multiple dosing. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50(1):65–74.

LaRue S, Malloy J. Evaluation of the dual-chamber pen design for the injection of exenatide once weekly for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;9(4):815–21.

Drucker DJ, Buse JB, Taylor K, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus twice daily for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority study. Lancet. 2008;372(9645):1240–50.

Iwamoto K, Nasu R, Yamamura A, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of exenatide once weekly in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr J. 2009;56(8):951–62.

Fineman MS, Mace KF, Diamant M, et al. Clinical relevance of anti-exenatide antibodies: safety, efficacy and cross-reactivity with long-term treatment. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(6):546–54.

Russell-Jones D, Cuddihy RM, Hanefeld M, et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus metformin, pioglitazone, and sitagliptin used as monotherapy in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-4): a 26-week double-blind study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):252–8.

Bergenstal RM, Wysham C, Macconell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus sitagliptin or pioglitazone as an adjunct to metformin for treatment of type 2 diabetes (DURATION-2): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9739):431–9.

Diamant M, Van Gaal L, Stranks S, et al. Once weekly exenatide compared with insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-3): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2234–43.

Blevins T, Pullman J, Malloy J, et al. DURATION-5: exenatide once weekly resulted in greater improvements in glycemic control compared with exenatide twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(5):1301–10.

Buse JB, Nauck M, Forst T, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-6): a randomised, open-label study. Lancet. 2013;381(9861):117–24.

Frías JP, Guja C, Hardy E, et al (2016) Exenatide once weekly plus dapagliflozin once daily versus exenatide or dapagliflozin alone in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin monotherapy (DURATION-8): a 28 week, multicentre, double-blind, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol;4(12):1004–16.

Henry RR, Klein EJ, Han J, Iqbal N. Efficacy and tolerability of exenatide once weekly over 6 years in patients with type 2 diabetes: an uncontrolled open-label extension of the DURATION-1 study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(11):677–86.

Diamant M, Van Gaal L, Guerci B, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus insulin glargine for type 2 diabetes (DURATION-3): 3-year results of an open-label randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(6):464–73.

Ji L, Onishi Y, Ahn CW, et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once-weekly vs exenatide twice-daily in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4(1):53–61.

Cho YM. Incretin physiology and pathophysiology from an Asian perspective. J Diabetes Investig. 2015;6(5):495–507.

Yabe D, Seino Y, Fukushima M, Seino S. β cell dysfunction versus insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes in East Asians. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(6):602.

Buse JB, Drucker DJ, Taylor KL, et al. DURATION-1: exenatide once weekly produces sustained glycemic control and weight loss over 52 weeks. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(6):1255–61.

Macconell L, Pencek R, Li Y, Maggs D, Porter L. Exenatide once weekly: sustained improvement in glycemic control and cardiometabolic measures through 3 years. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:31–41.

Diamant M, Van Gaal L, Stranks S, et al. Safety and efficacy of once-weekly exenatide compared with insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with type 2 diabetes over 84 weeks. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):683–9.

Norwood P, Liutkus JF, Haber H, Pintilei E, Boardman MK, Trautmann ME. Safety of exenatide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with a thiazolidinedione alone or in combination with metformin for 2 years. Clin Ther. 2012;34(10):2082–90.

Davies M, Heller S, Sreenan S, et al. Once-weekly exenatide versus once- or twice-daily insulin detemir: randomized, open-label, clinical trial of efficacy and safety in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin alone or in combination with sulfonylureas. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1368–76.

Vora JP, Malloy J, Zhou M, Hardy E, Iqbal N, Trautmann M. Daily blood glucose variability with exenatide once weekly vs. basal insulin in 3 RCTs. 74th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, 2014. Poster 997.

Scott DA, Boye KS, Timlin L, Clark JF, Best JH. A network meta-analysis to compare glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with exenatide once weekly or liraglutide once daily in comparison with insulin glargine, exenatide twice daily or placebo. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(3):213–23.

DeFronzo RA, Okerson T, Viswanathan P, Guan X, Holcombe JH, MacConell L. Effects of exenatide versus sitagliptin on postprandial glucose, insulin and glucagon secretion, gastric emptying, and caloric intake: a randomized, cross-over study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(10):2943–52.

van Bloemendaal L, Ten Kulve JS, la Fleur SE, Ijzerman RG, Diamant M. Effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 on appetite and body weight: focus on the CNS. J Endocrinol. 2014;221(1):T1–16.

Holst JJ. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(4):1409–39.

van Bloemendaal L, IJzerman RG, Ten Kulve JS, et al. GLP-1 receptor activation modulates appetite- and reward-related brain areas in humans. Diabetes. 2014;63(12):4186–96.

Kastin AJ, Akerstrom V. Entry of exendin-4 into brain is rapid but may be limited at high doses. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(3):313–8.

Kanoski SE, Fortin SM, Arnold M, Grill HJ, Hayes MR. Peripheral and central GLP-1 receptor populations mediate the anorectic effects of peripherally administered GLP-1 receptor agonists, liraglutide and exendin-4. Endocrinology. 2011;152(8):3103–12.

Blonde L, Pencek R, MacConell L. Association among weight change, glycemic control, and markers of cardiovascular risk with exenatide once weekly: a pooled analysis of patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14:12.

Wysham CH. In reply—long-term efficacy and safety of exenatide treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(9):1304–5.

Ussher JR, Drucker DJ. Cardiovascular biology of the incretin system. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(2):187–215.

Chiquette E, Toth PP, Ramirez G, Cobble M, Chilton R. Treatment with exenatide once weekly or twice daily for 30 weeks is associated with changes in several cardiovascular risk markers. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2012;8:621–9.

Guerci B, Schernthaner G, Gallwitz B, et al (2012) Long-term administration of exenatide and changes in body weight and markers of cardiovascular risk: a comparative study with glimepiride (Abstract 781). EASD annual meeting. (Berlin)

Vilsbøll T, Christensen M, Junker AE, Knop FK, Gluud LL. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on weight loss: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344:d7771.

Valensi P, Chiheb S, Fysekidis M. Insulin- and glucagon-like peptide-1-induced changes in heart rate and vagosympathetic activity: why they matter. Diabetologia. 2013;56(6):1196–200.

Linnebjerg H, Seger M, Kothare PA, Hunt T, Wolka AM, Mitchell MI. A thorough QT study to evaluate the effects of singledose exenatide 10 μg on cardiac repolarization in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;49(10):594–604.

Darpö B, Sager P, MacConell L, et al. Exenatide at therapeutic and supratherapeutic concentrations does not prolong the QTc interval in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(4):979–89.

Katout M, Zhu H, Rutsky J, et al. Effect of GLP-1 mimetics on blood pressure and relationship to weight loss and glycemia lowering: results of a systematic meta-analysis and meta-regression. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):130–9.

Younce CW, Niu J, Ayala J, et al. Exendin-4 improves cardiac function in mice overexpressing monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;76:172–6.

Nikolaidis LA, Elahi D, Hentosz T, et al. Recombinant glucagon-like peptide-1 increases myocardial glucose uptake and improves left ventricular performance in conscious dogs with pacing-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;110(8):955–61.

Zhao T, Parikh P, Bhashyam S, et al. Direct effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on myocardial contractility and glucose uptake in normal and postischemic isolated rat hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317(3):1106–13.

Timmers L, Henriques JP, de Kleijn DP, et al. Exenatide reduces infarct size and improves cardiac function in a porcine model of ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(6):501–10.

Lønborg J, Kelbæk H, Vejlstrup N, et al. Exenatide reduces final infarct size in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction and short-duration of ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(2):288–95.

Bernink FJ, Timmers L, Diamant M, et al. Effect of additional treatment with exenatide in patients with an acute myocardial infarction: the EXAMI study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(1):289–90.

Exenatide study of cardiovascular event lowering trial (EXSCEL): A trial to evaluate cardiovascular outcomes after treatment with exenatide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01144338. Accessed 1 Jan 2015.

Ridge T, Moretto T, MacConell L, et al. Comparison of safety and tolerability with continuous (exenatide once weekly) or intermittent (exenatide twice daily) GLP-1 receptor agonism in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(12):1097–103.

Paul SK, Maggs D, Klein K, Best JH. Dynamic risk factors associated with non-severe hypoglycemia in patients treated with insulin glargine or exenatide once weekly. J Diabetes. 2015;7(1):60–7.

Butler PC, Elashoff M, Elashoff R, Gale EA. A critical analysis of the clinical use of incretin-based therapies: are the GLP-1 therapies safe? Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):2118–25.

Nachnani JS, Bulchandani DG, Nookala A, et al. Biochemical and histological effects of exendin-4 (exenatide) on the rat pancreas. Diabetologia. 2010;53(1):153–9.

Gier B, Matveyenko AV, Kirakossian D, Dawson D, Dry SM, Butler PC. Chronic GLP-1 receptor activation by exendin-4 induces expansion of pancreatic duct glands in rats and accelerates formation of dysplastic lesions and chronic pancreatitis in the Kras(G12D) mouse model. Diabetes. 2012;61(5):1250–62.

Noel RA, Braun DK, Patterson RE, Bloomgren GL. Increased risk of acute pancreatitis and biliary disease observed in patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(5):834–8.

Wenten M, Gaebler JA, Hussein M, et al. Relative risk of acute pancreatitis in initiators of exenatide twice daily compared with other anti-diabetic medication: a follow-up study. Diabet Med. 2012;29(11):1412–8.

Garg R, Chen W, Pendergrass M. Acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes treated with exenatide or sitagliptin: a retrospective observational pharmacy claims analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2349–54.

Romley JA, Goldman DP, Solomon M, McFadden D, Peters AL. Exenatide therapy and the risk of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in a privately insured population. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(10):904–11.

Alves C, Batel-Marques F, Macedo AF. A meta-analysis of serious adverse events reported with exenatide and liraglutide: acute pancreatitis and cancer. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98(2):271–84.

Li L, Shen J, Bala MM, et al. Incretin treatment and risk of pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2366.

Spranger J, Gundert-Remy U, Stammschulte T. GLP-1-based therapies: the dilemma of uncertainty. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(1):20–3.

Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs–FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):794–7.

Investigation into GLP-1 based diabetes therapies concluded. European Medicines Agency. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2013/07/news_detail_001856.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1. Accessed 12 January 2015.

Gale EA. Response to comment on: Butler et al. A critical analysis of the clinical use of incretin-based therapies: are the GLP-1 therapies safe? Diabetes Care 2013;36:2118-2125. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(12):e214.

Knudsen LB, Nyborg NC, Svendsen CB, Vrang N, Moses AC. Comment on: Butler et al. A critical analysis of the clinical use of incretin-based therapies: are the GLP-1 therapies safe? Diabetes Care 2013;36:2118-2125. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(12):e213.

Bjerre Knudsen L, Madsen LW, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists activate rodent thyroid C-cells causing calcitonin release and C-cell proliferation. Endocrinology. 2010;151(4):1473–86.

An active surveillance program for cases of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC). ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01511393. Accessed 28 Dec 2014.

Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Hessler D, Bruhn D, Best JH. Patient perspectives on once-weekly medications for diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(2):144–9.

Best JH, Boye KS, Rubin RR, Cao D, Kim TH, Peyrot M. Improved treatment satisfaction and weight-related quality of life with exenatide once weekly or twice daily. Diabet Med. 2009;26(7):722–8.

Best JH, Rubin RR, Peyrot M, et al. Weight-related quality of life, health utility, psychological well-being, and satisfaction with exenatide once weekly compared with sitagliptin or pioglitazone after 26 weeks of treatment. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):314–9.

Saunders W, Nguyen H, Kalsekar I. Real-world comparative effectiveness of exenatide once weekly and liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. 74th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association. 2014. Poster 1192.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364–79.

Handelsman Y, Mechanick JI, Blonde L, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(Suppl 2):1–53.

Buse JB, Peters A, Russell-Jones D, et al (2015) Is insulin the most effective injectable antihyperglycaemic therapy? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(2):145–51.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):140–9.

Goldenberg R. Insulin plus incretin agent combination therapy in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(3):431–45.

Eng C, Kramer CK, Zinman B, Retnakaran R. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014;384(9961):2228–34.

Phase III study to evaluate safety and efficacy of added exenatide versus placebo to titrated basalinsulin glargine in inadequately controlled patients with type II diabetes mellitus clinicaltrials.gov. 2015. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02229383.

Inagaki N, Atsumi Y, Oura T, Saito H, Imaoka T. Efficacy and safety profile of exenatide once weekly compared with insulin once daily in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes treated with oral antidiabetes drug(s): results from a 26-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, multicenter, noninferiority study. Clin Ther. 2012;34(9):1892–1908e1.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Augusto Lovagnini Scher, MD, of ASST Nord Milan, Italy, who provided medical writing support (funded by AstraZeneca) and Elise Hardy, MD and Mary Beth DeYoung, PhD, Astra Zeneca UK who provided helpful review of the manuscript.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Disclosures

Stefano Genovese declares that he has participated in clinical research, scientific advisory boards, served as a consultant or received honoraria for Abbott Diabetes Care, Roma, Italy; AstraZeneca, Basiglio (MI), Italy; Boehringer Ingelheim, Milano, Italy; Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roma, Italy; Eli Lilly, Sesto Fiorentino (FI), Janssen, Cologno Monzese (MI), Italy; Lifescan, Milano, Italy; Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roma, Italy; Novartis, Origgio (MI), Italy; Novo Nordisk, Roma, Italy; Takeda, Roma, Italy.

Edoardo Mannucci declares having received consultancy fees, speaking honoraria, and/or research grants from AstraZeneca (Basiglio, Italy), BMS (Rome, Italy), Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, USA, and Sesto Fiorentino, Italy), Jannsen (Amsterdam, the Netherlards, and/or Milan, Italy), Merck (Rome, Italy), Novartis (Origgio, Italy), Novo Nordisk (Rome, Italy), Sanofi (Milan, Italy), and Takeda (Rome, Italy).

Antonio Ceriello declares advisory board membership at Bayer Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland and/or Milan, Italy), Bristol Myers Squibb (Rome, Italy), Danone (Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, USA, and/or Madrid, Spain and/or Sesto Fiorentino, Italy), Janssen (Amsterdam, the Netherlards, and/or Milan, Italy), Medtronic (Milan, Italy), Merck Sharp & Dome (Rome, Italy), Novartis (Origgio, Italy), Novo Nordisk (Copenaghen, Denmark), OM Pharma (Basel, Switzerland), Roche Diagnostics (Milan, Italy), Sanofi (Milan, Italy), Takeda (London, UK), and Unilever (Amsterdam, the Netherlands); consultancy for Bayer Pharma (Milan, Italy), Lifescan (Milan, Italy), Novartis (Origgio, Italy), and Roche Diagnostics (Milan, Italy); lectures for Astra Zeneca (Milan, Italy), Bayer Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland and/or Milan, Italy), Bayer Pharma (Milan, Italy), Boehringer Ingelheim (Milan, Italy), Bristol Myers Squibb (Rome, Italy), Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, USA, and/or Madrid, Spain and/or Sesto Fiorentino, Italy), Merck Sharp & Dome (Rome, Italy), Mitsubishi (Tokyo, Japan), Novartis (Origgio, Italy), Novo Nordisk (Copenaghen, Denmark), Nutricia (Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Sanofi (Paris, France and/or Barcelona, Spain and/or Milan, Italy), Servier (Paris, France), and Takeda (Rome, Italy); and research grants from Mitsubishi (Tokyo, Japan), Novartis (Origgio, Italy), and Novo Nordisk (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/C097F0602D7307D7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Genovese, S., Mannucci, E. & Ceriello, A. A Review of the Long-Term Efficacy, Tolerability, and Safety of Exenatide Once Weekly for Type 2 Diabetes. Adv Ther 34, 1791–1814 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0499-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0499-6