Abstract

Introduction

Assessing the consequences of chronic spontaneous/idiopathic urticaria (CSU) requires the evaluation of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) associated with the severity of CSU signs and symptoms. It is important to understand how signs, symptoms, and HRQoL change over time in CSU. Evidence is lacking on how closely changes in signs and symptoms of CSU are related to changes in HRQoL. The objective of this study was to assess the correlation between changes in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) of signs and symptoms, dermatologic quality of life (QoL), and urticaria-specific QoL.

Methods

Latent growth models (LGMs) were applied to longitudinal data from three randomized, Phase 3 clinical trials investigating the efficacy and safety of omalizumab in CSU.

Results

A near-perfect association between changes in signs and symptoms and changes in dermatologic and urticaria-specific QoLs was identified in each clinical trial when using LGMs (correlation coefficient range 0.88–0.92).

Conclusion

Evidence showed that changes in signs and symptoms are closely related to changes in HRQoL. However, analyses were performed on clinical trial results of an extremely effective treatment; a less effective treatment with much smaller changes over time may not show such close correlations. Results suggest that any of these PROMs may be used to understand changes in CSU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) or “chronic idiopathic urticaria”, itchy hives (wheals), angioedema, or both, occur for 6 or more weeks [1]. Chronic urticaria is common [2–4], impacting patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL), their ability to perform daily tasks, and their mental health [1, 5, 6].

CSU severity is assessed by evaluating signs [hives (changing daily)] and symptoms (itch). Patients count and record these using a daily diary such as the Urticaria Activity Score (UAS). HRQoL impact is assessed using generic, dermatologic-specific, or urticaria-specific [7] patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).

To gauge CSU treatment efficacy, clinicians must assess changes in the patient’s condition. Disease-specific HRQoL measures are more sensitive than generic ones in evaluating disease impact or detecting severity change or treatment response [8] and are more informative about CSU burden and changes in burden. Each PROM type provides different disease status information; sign measures do not provide HRQoL insights. However, if different PROMs showed similar patterns over time after changes in disease, clinicians could make inferences about a patient based on one of them. It is valuable to assess the extent to which different PROMs provide similar information about changes in CSU and its effects on quality of life (QoL), giving clinicians options for understanding patient experience.

Signs and symptoms of CSU and HRQoL show moderate correlation [9]. These correlations were based on only one time point and so did not assess the strength of relationships between changes in signs and symptoms and HRQoL changes after treatment. To understand this requires comparison of changes across multiple time points, in multiple outcome measures simultaneously. Traditionally, an analyst would create difference scores of a PROM between two time points for each patient and examine the correlation between the difference scores of the two PROMs. But, data may be ignored between two distal time points, such as baseline and the end of a study, and this is a piecewise approach, looking at changes between, say, baseline and a second time point, then between second and third time points, and so on. If change in the patient’s condition is non-linear, this approach only captures a portion of this change. Such analyses may have contributed to finding only moderate correlations between signs and symptoms of CSU and HRQoL measures. This approach poorly reflects the longer term patient experience and does not provide clinicians with the most accurate understanding of the effect of treatment.

We rejected traditional comparisons of change over time for the longitudinal modeling technique of latent growth modeling (LGM). LGM calculates individual patient change trajectories across all time points simultaneously; this allows comparisons between changes in outcomes from multiple measures in a single analysis and can account for non-linear changes in the patient’s condition. This technique was used to model cancer patients with anemia [10], but has rarely been applied to clinical trial data and has not been used within dermatology.

The objective of this study was to use LGM to assess the extent to which changes in three PROM types—CSU signs and symptoms, dermatologic and urticaria-specific QoL—are related in their patterns of change. The LGM results were compared with a traditional piecewise approach.

Methods

Data

Data were collected from three phase 3 trials of omalizumab in refractory CSU: ASTERIA I (40 weeks [11]), ASTERIA II (28 weeks [12]) and GLACIAL (40 weeks [13]) (Fig. 1). The patients in all trials were aged 12–75 years, with CSU refractory to H1 antihistamines (ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II) and refractory to H1 and H2 antihistamines with or without leukotriene receptor antagonists (GLACIAL). Treatment was administered four-weekly from baseline until 24 weeks in the 40-week trials (ASTERIA I, GLACIAL) and until 12 weeks in the 28-week trial (ASTERIA II). The studies conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki [14]; all were ethically approved and all patients gave informed consent.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Measures

Urticaria Activity Score (UAS) [15–17]

The UAS is a self-completed daily diary measuring CSU signs (hives) and symptoms (pruritus). Patients record twice-daily number of hives using a 0–3 range (0 = no hives; 3 = 12 or more hives in 12 h). Patients also record twice-daily pruritus severity, using a 0–3 range (0 = none; 3 = severe). The average daily score for the combined hives and pruritus scores is summed across 7 days to create a weekly score (UAS7) ranging from 0 to 42; higher scores indicate greater severity. Each trial required a UAS7 score of at least 16 for inclusion.

The UAS7 was calculated weekly during the trials. For ASTERIA I and GLACIAL, scores were reported at baseline; at weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 during treatment; and at weeks 24, 28, 32, 36, and 40 after treatment stopped. For ASTERIA II, the UAS7 was reported at baseline, at weeks 4, 8, and 12 during treatment and at weeks 16, 20, 24, and 28 after treatment stopped.

Dermatology Life Quality Index [18–20]

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is a 10-item self-reported questionnaire with a 1-week recall designed to assess QoL in skin diseases. It is validated in CSU [19, 20]. Each item has four response categories, ranging from “not at all” (score = 0) to “very much” (score = 3). Individual item scores are summed to a total score (range 0–30); higher scores indicate worse QoL.

For ASTERIA I and GLACIAL, the DLQI was administered at baseline, at weeks 4 and 12 during treatment and at weeks 24 and 40 after treatment stopped. For ASTERIA II, the DLQI was administered at baseline, at weeks 4 and 12 during treatment, and at week 28 after treatment stopped. The DLQI has been validated for individuals aged 16 years and older: the analysis used data from this age range.

Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life (QoL) Questionnaire [21]

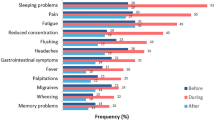

The Chronic Urticaria QoL Questionnaire (CU-Q2oL) is a 23-item, self-reported, urticaria-specific measure evaluating physical, psychosocial, and practical aspects of QoL. It has a 2-week recall period and six-dimensions: pruritus, swelling, impact on life activities, sleep problems, limits, and looks. Each item has five response categories ranging from “never” to “very much”. The total score ranges from 0 to 100; higher scores indicate worse QoL.

The CU-Q2oL was administered at the same times as the DLQI in all trials. As the instrument was developed within populations aged 18 years and older, the analysis used data from this age range.

Statistical Analyses

Latent growth models (LGM) were applied to data from the three trials using information from every available time point. LGM is a growth curve analysis based on structural equation modeling; it models individual trajectories of change, allowing correlation of patterns of changes between multiple outcome measures across multiple time points simultaneously [22]. Unlike analyses that compare mean changes among groups of patients, e.g., analyses of variance, LGMs examine how the change in one variable across all time points for a given patient matches the change in another variable for that patient. Analyses of mean change are limited to change between two time points and cannot correlate changes involving multiple variables. However, LGMs calculate a slope of change and its corresponding intercept for every patient for each variable and correlate those intercepts and slopes of change. The intercept is the value of the growth curve (slope of change) at the first assessment point, similar to the value of the initial observation for a patient.

LGMs can be conducted using “full information maximum likelihood”, a method for handling missing data [23]. An adjustment of the overall variance–covariance matrix (using maximum likelihood estimation) is based on the data from complete cases. LGMs automatically make use of information on all study participants, assuming data are missing at random. In contrast, traditional mean difference score analysis uses data only from patients with data at both time points, resulting in loss of information and precision, with potential bias.

The analyses were conducted in Mplus (version 7.11; Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, California, USA) separately for each trial, irrespective of treatment arm: patients’ responses on each PROM were pooled to create one analytic population per trial. The LGMs were conducted so that UAS7 scores were modeled across all time points simultaneously with DLQI and CU-Q2oL scores, allowing the intercepts and slopes of change to be correlated between the PROMs [22]. This allowed a direct comparison of change in one PROM with change in another. The correlations indicated how closely changes in the CSU signs and symptoms measure are reflected in changes in the QoL measures. The greater the correlation between the slopes of change in a pair of PROMs, the greater the similarity in what these two measures assessed in terms of change.

For illustration, a traditional piecewise analytic approach was conducted using UAS7 and DLQI scores from ASTERIA I. Difference scores, reflecting changes in UAS7 and DLQI scores, were calculated between pairs of time points for each PROM. Pearson’s correlations between each pair of difference scores were examined. These analyses used Stata (version 13.0; StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Patients’ characteristics at baseline were similar across each trial (Table 1), except more patients had baseline angioedema in GLACIAL versus ASTERIA II. Figure 2a–c show slopes of change in UAS7 and DLQI scores for ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II, and GLACIAL. The mean growth curves for each trial show a decrease in UAS7 and DLQI scores (CSU improvement) during the treatment period, through week 24 for ASTERIA I and GLACIAL, and through week 12 for ASTERIA II, but there was an increase in scores (CSU worsening) after treatment discontinuation in all three trials. This pattern of change was similar for the UAS7 and the DLQI, with strong correlations: ASTERIA I (0.91), ASTERIA II (0.88), and GLACIAL (0.92). For each standardized unit change in UAS7, the DLQI score changes by nearly the same standardized amount.

Table 2 shows the mean difference scores in ASTERIA I for selected pairs of time points for UAS7 and DLQI, and the correlations between each pair of difference scores. Unlike the strong correlation found using LGM (Fig. 2a), correlations based on piecewise mean difference scores were moderate (range 0.48–0.72). To understand the relationship between changes in UAS7 and DLQI in this approach requires examining multiple correlations between pairs of time points, making it more difficult to understand how changes in signs and symptoms of CSU are related to changes in dermatologic QoL. Such changes depend on the time frame: comparing segments within the same overall time period may yield different insights. For example, from baseline to week 12, the correlation is 0.57 between change in UAS7 and change in DLQI. However, the correlation is 0.64 between baseline and week 4 and 0.48 between week 4 and week 12.

Figure 3a–c show the slopes of change in UAS7 and the CU-Q2oL scores for ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II, and GLACIAL. As with UAS7 and DLQI, the growth curves reflect the mean changes in UAS7 and CU-Q2oL for each trial and show a decrease in UAS7 and CU-Q2oL scores (CSU improvement) during treatment. There was an increase in scores (CSU worsening) after treatment was discontinued. This pattern was similar for both the UAS7 and the CU-Q2oL. The strong correlations for ASTERIA I (0.90), ASTERIA II (0.89), and for GLACIAL (0.92) demonstrate that for each standardized unit change in UAS7, a patient’s score on the CU-Q2oL would change by nearly the same standardized amount.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria latent growth curve trajectories: correlations between slopes of change in the UAS7 and the CU-Q2OL for ASTERIA I (a), ASTERIA II (b), and GLACIAL (c). CU-Q 2 OL Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire, PRO patient-reported outcome, UAS7 Urticaria Activity Score over 7 days

Discussion

The LGM results showed a near-perfect association between changes in signs and symptoms and dermatologic QoL and changes in urticaria-specific QoL. These results, across three trials, provided validation of the findings, confidence in the results and evidence that in CSU changes in symptom severity are closely linked to changes in HRQoL. If improvement over time is found using the UAS7, it is highly likely that DLQI and CU-Q2oL scores will also improve, and vice versa. Consequently clinicians may choose to administer any of these PROMs and make inferences about changes over time in the others. However, these PROMs do not measure the same concepts; if clinicians wish to know something specific about HRQoL versus signs and symptoms, then the appropriate PROM should be used.

Small-to-moderate relationships between the UAS7 and the DLQI [24] and between the UAS7 and the CU-Q2oL [25] were reported using simple correlation analyses, also seen in Table 2. This piecewise approach based correlations on a single time point or comparing changes between two time points. The LGM results go beyond this using individual patient-level information across all time points simultaneously. Previous studies had restricted inferences due to the aggregate focus of the analyses. The present study uses an individual patient-level focus: the intercepts and slopes of change for every patient across all time points are used for correlations, providing more accurate, comprehensive understanding of changes.

The assessment period for the UAS7 (daily but summed to 1 week) and the recall period for the CU-Q2oL (2 weeks) are different, yet the correlations between them were as large as those between the UAS7 and the DLQI (both 1 week). This suggests patients’ HRQoL experiences of CSU are consistent and that different recall periods do not attenuate relationships among the PROMs.

Physicians have a choice of PROMs to assess the severity impact of CSU and treatment response. Clinicians can feel confident in using whichever measure is available and with whichever they are more familiar. If an improvement (or worsening) in signs and symptoms is found, it is highly likely that an improvement (or worsening) HRQoL is also experienced, and vice versa.

These results highlight the level of specificity and potential temporal ordering of HRQoL measures in CSU. Patient-reported symptoms are considered most “proximal” to treatment effects and the patient’s experience, while HRQoL is more “distal” to symptoms and treatment effects [26]. A disease-specific PROM is likely to be more proximal to symptoms and treatment effects than a more general HRQoL PROM [26]. However, in this study changes in CSU signs and symptoms (that treatment directly affects) are highly correlated with changes in the generic or CSU specific QoL measures; knowing one of these dimensions yields a very good understanding of the other two-dimensions of the patients’ experience of change.

One potential concern relates to the utilization of the DLQI and the CU-Q2oL. Some aspects of the psychometric properties of the DLQI have been criticized [27]; however, the DLQI has been validated for use in CSU [19, 28, 29] and the minimally important difference determined [20]. The CU-Q2oL is a relatively recent addition to the study of HRQoL in CSU and is recommended for assessment of HRQoL by international guidelines [1]. Validation of any measure is a multi-facetted process and this analysis provides evidence of these measures meeting another aspect of validation—that they change together very closely.

A second concern is that the analyses were of trial results of an extremely effective treatment. The analyses pooled all treatment arms, including placebo. The treatment is so effective that even when treatment and placebo patients were pooled, the treatment effect more than compensates for the lesser response of those on placebo. A less effective treatment that resulted in smaller changes might not show such close correlations.

Conclusion

This analysis of CSU PROMs provides support for clinicians that the results obtained from one of the PROMs about a change in a patient’s condition are highly likely to be indicative of similar changes in the PROM not administered. Thus, when using just one of the PROMs, inferences can be made about change in disease activity, response to treatment, and changes in HRQoL.

References

Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014;69(7):868–87.

Töndury B, Muehleisen B, Ballmer-Weber BK, et al. The Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure (PRISM) instrument reveals a high burden of suffering in patients with chronic urticaria. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21(2):93–100.

Maurer M, Magerl M, Metz M, et al. Revisions to the international guidelines on the diagnosis and therapy of chronic urticaria. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11(10):971–8.

Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66(3):317–30.

O’Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, et al. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136(2):197–201.

Staubach P, Eckhardt-Henn A, Dechene M, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic urticaria is differentially impaired and determined by psychiatric comorbidity. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(2):294–8.

Baiardini I, Braido F, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Recommendations for assessing patient-reported outcomes and health-related quality of life in patients with urticaria: a GA(2)LEN taskforce position paper. Allergy. 2011;66(7):840–4.

Wiebe S, Guyatt G, Weaver B, et al. Comparative responsiveness of generic and specific quality-of-life instruments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(1):52–60.

Koti I, Weller K, Makris M, et al. Disease activity only moderately correlates with quality of life impairment in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Dermatology. 2013;226(4):371–9.

Stull DE, Vernon MK, Legg JC, et al. Use of latent growth curve models for assessing the effects of darbepoetin alfa on hemoglobin and fatigue. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31:172–9.

Saini SS, Bindslev-Jensen C, Maurer M, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria who remain symptomatic on H1 antihistamines: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(1):67–75.

Maurer M, Rosén K, Hsieh HJ, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):924–35.

Kaplan A, Ledford D, Ashby M, et al. Omalizumab in patients with symptomatic chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria despite standard combination therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(1):101–9.

World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Seoul, South Korea: World Medical Association, October 2008.

Mathias SD, Dreskin SC, Kaplan A, et al. Development of a daily diary for patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(2):142–8.

Mathias SD, Crosby RD, Rosen K, et al. Estimating the minimal important difference (MID) of the measures in the Urticaria Patient Daily Diary (UPDD): updated findings using data from the Asteria I, Asteria II, and Glacial studies of omalizumab in chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(suppl 2):AB118.

Zazzali JL, Mathias SD, Flood EM, et al. Development and validation of the Urticaria Patient Daily Diary (UPDD). In: Presented at the 4th International Consensus Meeting on Urticaria; Berlin, Germany. 28–29 November 2012.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–6.

Lennox RD, Leahy MJ. Validation of the Dermatology Life Quality Index as an outcome measure for urticaria-related quality of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93(2):142–6.

Shikiar R, Harding G, Leahy M, et al. Minimal important difference (MID) of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): results from patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:36.

Baiardini I, Pasquali M, Braido F, et al. A new tool to evaluate the impact of chronic urticaria on quality of life: Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-QoL). Allergy. 2005;60(8):1073–8.

Stull DE. Analyzing growth and change: latent variable growth curve modelling with an application to clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(1):47–59.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010.

Młynek A, Zalewska-Janowska A, Martus P, et al. How to assess disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria? Allergy. 2008;63(6):777–80.

Ye YM, Park JW, Kim SH, et al. Clinical evaluation of the computerized chronic urticaria-specific quality of life questionnaire in Korean patients with chronic urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(7):722–8.

Cleeland CS. Quality of life assessment in symptom management trials: symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient-reported outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007;37:16–21.

Nijsten T. Dermatology Life Quality Index: time to move forward. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:11–3.

Basra MKA, Fenech R, Gatt RM, et al. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994–2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:997–1035.

Finlay AY, Basra MKA, Piguet V, Salek S. DLQI: a paradigm shift to patient-centred outcomes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2464–5.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. All authors had access to all relevant aggregated study data required to understand and report research findings. Donald E. Stull and Katherine Houghton take joint responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. However, results were shared with co-authors at each step, and their input was sought regarding discussion and implications of the results. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published prior to submission. Editorial assistance for this study was provided by Gail Zona of RTI Solutions, Manchester, UK, and funded by Novartis.

Disclosures

Donald E. Stull, Doreen McBride and Katherine Houghton are employees of RTI Health Solutions, which provides consulting and other research services to pharmaceutical, device, government, and nongovernment organizations. In their salaried positions, they work with a variety of companies and organizations. They receive no payment or honoraria directly from these organizations for services rendered. Andrew Y. Finlay has received consultancy fees by Novartis Pharma AG for his involvement in the current study, and is also joint copyright owner of the Dermatology Life Quality Index; Cardiff University gains some income from its use. Ari Gnanasakthy is currently an employee of RTI Health Solutions, but was an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation at the time this research was conducted. Maria-Magdalena Balp is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Stull, D.E., McBride, D., Houghton, K. et al. Assessing Changes in Chronic Spontaneous/Idiopathic Urticaria: Comparisons of Patient-Reported Outcomes Using Latent Growth Modeling. Adv Ther 33, 214–224 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0282-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0282-0

Keywords

Profiles

- Katherine Houghton View author profile

- Ari Gnanasakthy View author profile