Abstract

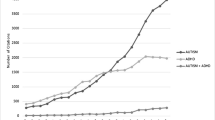

It remains unclear whether autism and Asperger’s disorder (AD) exist on a symptom continuum or are separate disorders with discrete neurobiological underpinnings. In addition to impairments in communication and social cognition, motor deficits constitute a significant clinical feature in both disorders. It has been suggested that motor deficits and in particular the integrity of cerebellar modulation of movement may differentiate these disorders. We used a simple volitional saccade task to comprehensively profile the integrity of voluntary ocular motor behaviour in individuals with high functioning autism (HFA) or AD, and included measures sensitive to cerebellar dysfunction. We tested three groups of age-matched young males with normal intelligence (full scale, verbal, and performance IQ estimates >70) aged between 11 and 19 years; nine with AD, eight with HFA, and ten normally developing males as the comparison group. Overall, the metrics and dynamics of the voluntary saccades produced in this task were preserved in the AD group. In contrast, the HFA group demonstrated relatively preserved mean measures of ocular motricity with cerebellar-like deficits demonstrated in increased variability on measures of response time, final eye position, and movement dynamics. These deficits were considered to be consistent with reduced cerebellar online adaptation of movement. The results support the notion that the integrity of cerebellar modulation of movement may be different in AD and HFA, suggesting potentially differential neurobiological substrates may underpin these complex disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fombonne E. The prevalence of autism. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:87–9.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders IV-TR. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 2000.

Teitelbaum O, Benton T, Shah PK, Prince A, Kelly JL, Teitelbaum P. Eshkol-Wachman movement notation in diagnosis: the early detection of Asperger’s syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11909–14.

Landa R, Garrett-Mayer E. Development in infants with autism spectrum disorders: a prospective study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:629–38.

Teitelbaum P, Teitelbaum O, Nye J, Fryman J, Maurer RG. Movement analysis in infancy may be useful for early diagnosis of autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13982–7.

Nayate A, Bradshaw JL, Rinehart NJ. Autism and Asperger’s disorder: are they movement disorders involving the cerebellum and/or basal ganglia? Brain Res Bull. 2005;67:327–34.

Rinehart NJ, Bellgrove MA, Tonge BJ, Brereton AV, Howells-Rankin D, Bradshaw JA. An examination of movement kinematics in young people with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder: further evidence for a motor planning deficit. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:757–67.

Rinehart NJ, Tonge BJ, Bradshaw JA, Iansek R, Enticott PG, McGinley J. Gait function in high functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder: evidence for basal-ganglia & cerebellar involvement? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15:256–64.

Rinehart NJ, Tonge BJ, Iansek R, McGinley J, Brereton AV, Enticott PG, et al. Gait function in newly diagnosed children with autism: cerebellar and basal ganglia related motor disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48:819–24.

Rosenbaum DA. Human motor control. London: Academic; 1991.

Salmond CH, de Haan M, Friston KJ, Gadian DG, Vargha-Khadem F. Invesigating individual differences in brain abnormalities in autism. Phil Trans R Soc Lond. 2003;358:405–13.

Allen G, Courchesne E. Differential effects of developmental cerebellar abnormality on cognitive and motor functions in the cerebellum: an fMRI study of autism. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:262–73.

Allen G, Muller RA, Courchesne E. Cerebellar function in autism: functional magnetic resonance image activation during a simple motor task. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:269–78.

Hallahan B, Daly EM, McAlonan G, Loth E, Toal F, O’Brien F, et al. Brain morphometry volume in autistic spectrum disorder: a magnetic resonance imaging study of adults. Psychol Med. 2009;39:337–46.

Kaufmann WE, Cooper KL, Mostofsky SH, Capone GT, Kates WR, Newschaffer CJ, et al. Specificity of cerebellar vermian abnormalities in autism: a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:463–70.

Courchesne E, Saitoh O, Yeung-Courchesne R, Press GA, Lincoln AJ, Haas RH, et al. Abnormality of cerebellar vermian lobules VI and VII in patients with infantile autism: identification of hypoplastic and hyperplastic subgroups with MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:123–30.

Bailey A, Luthert P, Dean A, Harding B, Janota I, Montgomery M, et al. A clinicopathological study of autism. Brain. 1998;121:889–905.

Fatemi SH, Halt AR, Realmuto G, Earle J, Kist DA, Thuras P, et al. Purkinje cell size is reduced in cerebellum of patients with autism. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2002;22:171–5.

Mostofsky SH, Powell SK, Simmonds DJ, Goldberg MC, Caffo B, Pekar JJ. Decreased connectivity and cerebellar activity in autism during motor task performance. Brain. 2009;132:2413–25.

McAlonan M, Daly E, Kumari V, Critchley HD, Van Amelsvoort T, Suckling J, et al. Brain anatomy and sensorimotor gating in Asperger’s syndrome. Brain. 2002;127:1594–606.

Catani M, Jones DK, Daly E, Embiricos N, Deeley Q, Pugliese L, et al. Altered cerebellar feedback projections in Asperger syndrome. Neuroimage. 2008;41:1184–91.

McAlonan GM, Cheung C, Cheung V, Wong N, Suckling J, Chua SE. Differential effects on white-matter systems in high-functioning autism and Asperger’s syndrome. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1885–93.

McAlonan GM, Suckling J, Wong N, Cheung V, Lienenkaemper N, Cheung C, et al. Distinct patterns of grey matter abnormality in high-functioning autism and Asperger’s syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:1287–95.

Qiu A, Adler M, Crocetti D, Miller M, Mostofsky SH. Basal ganglia shapes predict social, communication, and motor dysfunctions in boys with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:539–51.

Hoshi E, Tremblay L, Feger J, Carras PL, Strick PL. The cerebellum communicates with the basal ganglia. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1491–3.

Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The neurology of eye movements. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Takarae Y, Minshew NJ, Luna B, Krisky CM, Sweeney JA. Pursuit eye movement deficits in autism. Brain. 2004;127:2584–94.

Nowinski CV, Minshew NJ, Luna B, Takarae Y, Sweeney J. Oculomotor studies of cerebellar function in autism. Psychiatry Res. 2005;137:11–9.

Goldberg MC, Landa R, Lasker A, Cooper L, Zee DS. Evidence of normal cerebellar control of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) in children with high-functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:519–24.

Luna B, Doll SK, Hegedus SJ, Minshew NJ, Sweeney JA. Maturation of executive function in Autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:474–81.

Luna B, Minshew NJ, Garver KE, Lazar NA, Thulborn KR, Eddy WF, et al. Neocortical system abnormalities in autism: an fMRI study of spatial working memory. Neurology. 2002;59:834–40.

Minshew NJ, Luna B, Sweeney JA. Oculomotor evidence for neocortical systems but not cerebellar dysfunction in autism. Neurology. 1999;52:917–22.

Takarae Y, Minshew NJ, Luna B, Sweeney JA. Oculomotor abnormalities parallel cerebellar histopathology in autism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1359–61.

Olk B, Kingstone A, Olk B, Kingstone A. Why are antisaccades slower than prosaccades? A novel finding using a new paradigm. NeuroReport. 2003;14:151–5.

Hallett PE, Adams BD. The predictability of saccadic latency in a novel voluntary oculomotor task. Vis Res. 1980;20:329–39.

Munoz DP, Everling S. Look away: the anti-saccade task and the voluntary control of eye movement. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:218–28.

Kleinhans N, Akshoomoff N, Delis DC. Executive functions in Autism and Asperger’s disorder: flexibility, fluency, and inhibition. Dev Neuropsychol. 2005;27:379–401.

Manjiviona J, Prior M. Neuropsychological profiles of children with Asperger syndrome and autism. Autism. 1999;3:327–56.

Ozonoff S, Jensen J. Specific executive function profiles in three neurodevelopmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999;29:171–7.

Rinehart NJ, Bradshaw JL, Brereton AV, Tonge BJ. A clinical and neurobehavioural review of high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36:762–70.

Verte S, Geurts HM, Roeyers H, Oosterlaan J, Sergeant JA. Executive functioning in children with autism and Tourette syndrome. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17:415–45.

Goldberg MC, Lasker AG, Zee DS, Garth E, Tien A, Landa RJ. Deficits in the initiation of eye movements in the absence of a visual target in adolescents with high functioning autism. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:2039–49.

Thakkar KN, Polli FE, Joseph RM, Tuch DS, Hadjikhani N, Barton JJ, et al. Response monitoring, repetitive behaviour and anterior cingulate abnormalities in autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Brain. 2008;131:2464–78.

Manoach D, Lindgren K, Barton J. Deficient saccadic inhibition in Asperger’s disorder and the social-emotional processing disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1719–26.

Robinson FR, Fuchs AF. The role of the cerebellum in voluntary eye movements. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:981–1004.

Takagi M, Zee DS, Tamargo RJ. Effect of dorsal cerebellar lesions on saccades and pursuit in monkeys. Society of Neuroscience Abstracts. 1996;22:1458.

Barash S, Melikyan A, Sivakov A, Zhang M, Glickstein M, Thier P. Saccadic dysmetria and adaptation after lesions of the cerebellar cortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10931–9.

Ceravolo R, Fattori B, Nuti A, Dell’Agnello G, Cei G, Casani A, et al. Contribution of cerebellum and brainstem in the control of eye movement: evidence from a functional study in a clinical model. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;105(1):32–9.

Fielding J, Corben L, Cremer P, Millist L, White O, Delatycki M. Disruption to higher order processes in Friedreich ataxia. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:235–42.

Fahey MC, Cremer PD, Aw ST, Millist L, Todd MJ, White OB, et al. Vestibular, saccadic and fixation abnormalities in genetically confirmed Friedreich ataxia. Brain. 2008;131:1035–45.

Reuter B, Jager M, Bottlender R, Kathmann N. Impaired action control in schizophrenia: the role of volitional saccade initiation. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:1840–8.

Honda H. Idiosyncratic left-right asymmetries of saccadic latencies: examination in a gap paradigm. Vision Res. 2002;42:1437–45.

Enticott PG, Bradshaw JL, Iansek R, Tonge BJ, Rinehart NJ, Enticott PG, et al. Electrophysiological signs of supplementary-motor-area deficits in high-functioning autism but not Asperger syndrome: an examination of internally cued movement-related potentials. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:787–91.

Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659–85.

Tonge BJ, Brereton AV, Gray KM, Einfeld SL. Behavioural and emotional disturbance in high-functioning autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism. 1999;3:117–30.

Lebedev S, Van Gelder P, Tsui W. Square-root relations between main saccadic parameters. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2750–8.

Bahill AT, Clark MR, Stark L. The main sequence, a tool for studying human eye movements. Mathematics Biosciences. 1975;24:191–204.

Hutton SB. Cognitive control of saccadic eye movements. Brain Cogn. 2008;68:327–40.

Takagi M, Zee DS, Tamargo RJ. Effects of lesions of the oculomotor vermis on eye movements in primate: saccades. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1911–31.

Robinson FR. Role of the cerebellum in movement control and adaptation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:755–62.

Ohki M, Kitazawa H, Hiramatsu T, Kaga K, Kitamura T, Yamada J, et al. Role of primate cerebellar hemisphere in voluntary eye movement control revealed by lesion effects. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:934–47.

Robinson FR, Straube A, Fuchs AF. Role of the caudal fastigial nucleus in saccade generation. II. Effects of muscimol inactivation. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1741–58.

Bastian AJ. Learning to predict the future: the cerebellum adapts feedforward movement control. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:645–9.

Fabbri-Destro M, Cattaneo L, Boria S, Rizzolatti G. Planning actions in autism. Exp Brain Res. 2009;192:521–5.

Takarae Y, Minshew NJ, Luna B, Sweeney JA. Atypical involvement of frontostriatal systems during sensorimotor control in autism. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2007;156:117–27.

Allen G, Müller R-A, Courchesne E. Cerebellar function in autism: functional magnetic resonance image activation during a simple motor task. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:269–78.

Belmonte MK, Allen G, Beckel-Mitchener A, Boulanger LM, Carper RA, Webb SJ. Autism and abnormal development of brain connectivity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9228–31.

Pierce K, Courchesne E. Evidence for a cerebellar role in reduced exploration and stereotyped behavior in autism.[see comment]. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:655–64.

Schmahmann JD. Disorders of the cerebellum: ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16:367–78.

Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC. Cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1997;41:433–40.

Middleton FA, Strick PL. Anatomical evidence for cerebellar and basal ganglia involvement in higher cognitive function. Science. 1994;266:458–61.

Daum I, Snitz BE, Ackermann H. Neuropsychological deficits in cerebellar syndromes. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2001;13:268–75.

Gordon N. The cerebellum and cognition. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11:232–4.

Van Mier HI, Petersen SE. Role of the cerebellum in motor cognition. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;978:334–53.

Rapoport M, van Reekum R, Mayberg H. The role of the cerebellum in cognition and behavior: a selective review.[see comment]. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:193–8.

Happe F, Frith U. The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:5–25.

Minshew NJ, Sweeney J, Luna B. Autism as a selective disorder of complex information processing and underdevelopment of neocortical systems. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:S14–5.

Szatmari P. The classification of autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder. Can Rev Psychiatry. 2000;45:731–8.

Swedo S, Cook Jr E, Happe F, Harris J, Kaufmann W, King B, et al. American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Development. 299.80 Asperger’s Disorder. Available at: http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=97. Accessed 7 August 2010

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the time and effort of all the participants and their families involved in this study. We thank Lynette Millist for technical support. This research was supported by Monash University, an Autism Speaks Award (#CF06-0154) awarded to Dr Joanne Fielding, and two grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council Australia: Fellowship grant (#454811) awarded to Dr Joanne Fielding and Project Grant (#585801) awarded to Dr Joanne Fielding, Dr Nicole Rinehart, Prof B.Tonge and A/Prof O. White.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stanley-Cary, C., Rinehart, N., Tonge, B. et al. Greater Disruption to Control of Voluntary Saccades in Autistic Disorder than Asperger’s Disorder: Evidence for Greater Cerebellar Involvement in Autism?. Cerebellum 10, 70–80 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-010-0229-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-010-0229-y