Abstract

Purpose of Review

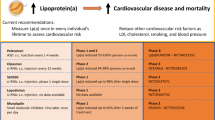

Lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) is a proinflammatory and atherogenic molecule that is emerging as an important biomarker of cardiovascular (CV) risk. It has been implicated in the pathogenesis of both atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and aortic valve stenosis. An estimated 10–30% of the global population has elevated Lp(a) levels. Screening for and treating elevated Lp(a) represents an opportunity to reduce risk for adverse CV events.

Recent Findings

Current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and National Lipid Association recommend Lp(a) testing in high-risk individuals. The European Atherosclerosis Society takes a stronger stance, recommending once in a lifetime lipoprotein(a) testing across the general population. Few recommendations currently exist regarding treatment of elevated lipoprotein(a).

Summary

Because elevated Lp(a) is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, further screening and treatment is necessary. Ongoing clinical trials with RNA based therapeutics such as antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNA show great promise for lowering Lp(a). More data is needed to demonstrate improved cardiovascular outcomes from Lp(a) reduction. Lp(a) should be incorporated into clinical practice as a useful biomarker to guide decisions about ASCVD risk and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Sticchi E, et al. Apolipoprotein(a) Kringle-IV type 2 copy number variation is associated with venous thromboembolism. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149427.

Nielsen LB. Atherogenecity of lipoprotein(a) and oxidized low density lipoprotein: insight from in vivo studies of arterial wall influx, degradation and efflux. Atherosclerosis. 1999;143:229–43.

Sotiriou SN, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic plaques recruits inflammatory cells through interaction with Mac-1 integrin. FASEB J. 2006;20:559–61.

Nordestgaard BG, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2844–53.

Anglés-Cano E. Structural basis for the pathophysiology of lipoprotein(a) in the athero-thrombotic process. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1997;30:1271–80.

Collaboration ERF, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. 2009;302:412–23.

Momiyama Y, et al. Associations between serum lipoprotein(a) levels and the severity of coronary and aortic atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2012;222:241–4.

van der Valk FM, et al. Oxidized phospholipids on lipoprotein(a) elicit arterial wall inflammation and an inflammatory monocyte response in humans. Circulation. 2016;134:611–24.

Tsimikas S, et al. Oxidized phospholipids, Lp(a) lipoprotein, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:46–57.

Bergmark C, et al. A novel function of lipoprotein [a] as a preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2230–9.

Leibundgut G, et al. Determinants of binding of oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein (a) and lipoprotein (a). J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2815–30.

Lee S, et al. Role of phospholipid oxidation products in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2012;111:778–99.

Miller YI, et al. Oxidation-specific epitopes are danger-associated molecular patterns recognized by pattern recognition receptors of innate immunity. Circ Res. 2011;108:235–48.

Leibundgut G, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S. Oxidation-specific epitopes and immunological responses: Translational biotheranostic implications for atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:168–79.

Taleb A, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S. Oxidized phospholipids on apoB-100-containing lipoproteins: a biomarker predicting cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular events. Biomark Med. 2011;5:673–94.

Tsimikas S, et al. Oxidation-specific biomarkers, prospective 15-year cardiovascular and stroke outcomes, and net reclassification of cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2218–29.

Yeang C, Wilkinson MJ, Tsimikas S. Lipoprotein(a) and oxidized phospholipids in calcific aortic valve stenosis. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2016;31:440–50.

Tsimikas S, et al. Oxidation-specific biomarkers, lipoprotein(a), and risk of fatal and nonfatal coronary events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:946–55.

Kiechl S, et al. Oxidized phospholipids, lipoprotein(a), lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 activity, and 10-year cardiovascular outcomes: prospective results from the Bruneck study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1788–95.

Kronenberg F, Utermann G. Lipoprotein(a): resurrected by genetics. J Intern Med. 2013;273:6–30.

Boerwinkle E, Menzel HJ, Kraft HG, Utermann G. Genetics of the quantitative Lp(a) lipoprotein trait III Contribution of Lp(a) glycoprotein phenotypes to normal lipid variation. Hum Genet. 1989;82:73–8.

Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301:2331–9.

Schmidt K, Noureen A, Kronenberg F, Utermann G. Structure, function, and genetics of lipoprotein (a). J Lipid Res. 2016;57:1339–59.

Marcovina SM, Albers JJ. Lipoprotein (a) measurements for clinical application. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:526–37.

Cegla J, et al. HEART UK consensus statement on Lipoprotein(a): a call to action. Atherosclerosis. 2019;291:62–70.

Yeang C, et al. Effect of pelacarsen on lipoprotein(a) cholesterol and corrected low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1035–1046. Yeang et al. assessed the effect of Pelacarsen on directly measured Lp(a) and LDL-C as a therapeutic option for elevated Lp(a) levels. The study demonstrated that Pelacarsen led to dose-dependent reduction in Lp(a) levels and mild reductions in LDL-c for patients with elevated Lp(a). The highest dose caused a 67% decrease in Lp(a) levels with the effect lasting for months, and the drug was overall well tolerated by study participants.

Enas EA, Varkey B, Dharmarajan TS, Pare G, Bahl VK. Lipoprotein(a): An independent, genetic, and causal factor for cardiovascular disease and acute myocardial infarction. Indian Heart J. 2019;71:99–112.

Anand SS, et al. Elevated lipoprotein(a) levels in South Asians in North America. Metabolism. 1998;47:182–4.

Tavridou A, Unwin N, Bhopal R, Laker MF. Predictors of lipoprotein(a) levels in a European and South Asian population in the Newcastle Heart Project. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:686–92.

Tsimikas S, et al. NHLBI Working Group recommendations to reduce lipoprotein(a)-mediated risk of cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:177–92.

Murphy SA, et al. Reduction in total cardiovascular events with ezetimibe/simvastatin post-acute coronary syndrome: the IMPROVE-IT Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:353–61.

Thanassoulis G. Lipoprotein (a) in calcific aortic valve disease: from genomics to novel drug target for aortic stenosis. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:917–24.

Clarke R, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518–28.

Kamstrup PR, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of myocardial infarction in the general population: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:176–84.

Maranhão RC, Carvalho PO, Strunz CC, Pileggi F. Lipoprotein (a): structure, pathophysiology and clinical implications. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2014;103:76–84.

Wu HD, et al. High lipoprotein(a) levels and small apolipoprotein(a) sizes are associated with endothelial dysfunction in a multiethnic cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1828–33.

Dweck MR, Boon NA, Newby DE. Calcific aortic stenosis: a disease of the valve and the myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1854–63.

Olsson M, Thyberg J, Nilsson J. Presence of oxidized low density lipoprotein in nonrheumatic stenotic aortic valves. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1218–22.

O’Brien KD, et al. Apolipoproteins B, (a), and E accumulate in the morphologically early lesion of ‘degenerative’ valvular aortic stenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:523–32.

Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk The Task Force for the management of …. Eur Heart J. 2020.

Grundy SM, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082–143.

Wilson PWF, et al. Lipid measurements in the management of cardiovascular diseases: Practical recommendations a scientific statement from the national lipid association writing group. J Clin Lipidol. 2021;15:629–48.

Wilson DP, et al. Use of Lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice: A biomarker whose time has come. A scientific statement from the National Lipid Association. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13:374–92.

Mach F, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:111–88.

Boffa MB, Koschinsky ML. Lipoprotein (a): truly a direct prothrombotic factor in cardiovascular disease? J Lipid Res. 2016;57:745–57.

Borén J, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: pathophysiological, genetic, and therapeutic insights: a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2313–30.

Khera AV, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations, rosuvastatin therapy, and residual vascular risk: an analysis from the JUPITER Trial (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin). Circulation. 2014;129:635–42.

Langsted A, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. High lipoprotein(a) and high risk of mortality. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2760–70.

Chennamsetty I, et al. Nicotinic acid inhibits hepatic APOA gene expression: studies in humans and in transgenic mice. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2405–12.

Carlson LA, Hamsten A, Asplund A. Pronounced lowering of serum levels of lipoprotein Lp(a) in hyperlipidaemic subjects treated with nicotinic acid. J Intern Med. 1989;226:271–6.

Sahebkar A, Reiner Ž, Simental-Mendía LE, Ferretti G, Cicero AFG. Effect of extended-release niacin on plasma lipoprotein(a) levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Metabolism. 2016;65:1664–78.

Parish S, et al. Impact of apolipoprotein(a) isoform size on lipoprotein(a) lowering in the HPS2-THRIVE study. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e001696.

Albers JJ, et al. Relationship of apolipoproteins A-1 and B, and lipoprotein(a) to cardiovascular outcomes: the AIM-HIGH trial (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglyceride and Impact on Global Health Outcomes). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1575–9.

Investigators TA-H & The AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255–2267.

Cao Y-X, Liu H-H, Li S, Li J-J. A Meta-analysis of the effect of PCSK9-monoclonal antibodies on circulating lipoprotein (a) levels. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2019;19:87–97.

Gaudet D, et al. Effect of alirocumab, a monoclonal proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 antibody, on lipoprotein(a) concentrations (a pooled analysis of 150 mg every two weeks dosing from phase 2 trials). Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:711–715. Gaudet et al. analyzed data from the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial with regards to Lp(a) levels. For patients with hypercholesterolemia, treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor reduced Lp(a) levels by 30% compared to placebo. Reduction in Lp(a) was only weakly correlated with magnitude of reduction in LDL-C.

Raal FJ, et al. Reduction in lipoprotein(a) with PCSK9 monoclonal antibody evolocumab (AMG 145): a pooled analysis of more than 1,300 patients in 4 phase II trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1278–88.

Sabatine MS, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713–22.

O’Donoghue ML, et al. Lipoprotein(a), PCSK9 inhibition, and cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2019;139:1483–92.

Bergmark BA, et al. An exploratory analysis of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibition and aortic stenosis in the FOURIER Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:709–13.

Bittner VA, et al. Effect of alirocumab on lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular risk after acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:133–44.

Takagi H, Umemoto T. Atorvastatin decreases lipoprotein(a): a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int J Cardiol. 2012;154:183–6.

Van Wissen S, et al. Long term statin treatment reduces lipoprotein (a) concentrations in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Heart. 2003;89:893–6.

Tsimikas S, Gordts PLSM, Nora C, Yeang C, Witztum JL. Statin therapy increases lipoprotein(a) levels. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2275–84.

Awad K, et al. Effect of ezetimibe monotherapy on plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drugs. 2018;78:453–62.

Schettler VJJ, et al. The German Lipoprotein Apheresis Registry (GLAR) - almost 5 years on. Clin Res Cardiol Suppl. 2017;12:44–9.

Roeseler E, et al. Lipoprotein apheresis for lipoprotein(a)-associated cardiovascular disease: prospective 5 years of follow-up and apolipoprotein(a) characterization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:2019–27.

Khan TZ, et al. Apheresis as novel treatment for refractory angina with raised lipoprotein(a): a randomized controlled cross-over trial. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1561–9.

Moriarty PM, Hemphill L. Lipoprotein apheresis. Cardiol Clin. 2015;33:197–208.

Suk Danik J, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Lipoprotein(a), hormone replacement therapy, and risk of future cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:124–31.

Kim CJ, Jang HC, Cho DH, Min YK. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on lipoprotein(a) and lipids in postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:275–81.

Shlipak MG, et al. Estrogen and progestin, lipoprotein(a), and the risk of recurrent coronary heart disease events after menopause. JAMA. 2000;283:1845–52.

Wu JH, Lee IN. Studies of apolipoprotein (a) promoter from subjects with different plasma lipoprotein (a) concentrations. Clin Biochem. 2003;36:241–6.

Ferretti G, et al. Raloxifene lowers plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31:197–208.

Kaplan SA, Lin J, Johnson-Levonas AO, Shah AK, Meehan AG. Increased occurrence of marked elevations of lipoprotein(a) in ageing, hypercholesterolaemic men with low testosterone. Aging Male. 2010;13:40–3.

O’Halloran DJ, Wieringa G, Tsatsoulis A, Shalet SM. Increased serum lipoprotein(a) concentrations after growth hormone (GH) treatment in patients with isolated GH deficiency. Ann Clin Biochem. 1996;33:330–4.

Olivecrona H, et al. Hormonal regulation of serum lipoprotein(a) levels. Contrasting effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:847–9.

Kaliaperumal R, William E, Selvam T, Krishnan SM. Relationship between lipoprotein(a) and thyroid hormones in hypothyroid patients. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:37–9.

Sokolov EI, Metel’skaia VA, Perova NV, Shchukina GN. [Hormonal regulation of lipoprotein metabolism: the role in pathogenesis of coronary heart disease]. Kardiologiia 2006;46:4–9.

Serban M-C, et al. Impact of L-carnitine on plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–11.

Chasman DI, et al. Polymorphism in the apolipoprotein(a) gene, plasma lipoprotein(a), cardiovascular disease, and low-dose aspirin therapy. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:371–6.

Shiffman D, et al. Coronary heart disease risk, aspirin use, and apolipoprotein(a) 4399Met allele in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:179–80.

McNeil JJ, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1519–28.

ASCEND Study Collaborative Group et al. effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1529–1539.

Crooke ST, Witztum JL, Bennett CF, Baker BF. RNA-targeted therapeutics. Cell Metab. 2018;27:714–39.

Merki E, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide directed to human apolipoprotein B-100 reduces lipoprotein(a) levels and oxidized phospholipids on human apolipoprotein B-100 particles in lipoprotein(a) transgenic mice. Circulation. 2008;118:743–53.

Santos RD, et al. Mipomersen, an antisense oligonucleotide to apolipoprotein B-100, reduces lipoprotein(a) in various populations with hypercholesterolemia: results of 4 phase III trials. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:689–99.

Merki E, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide lowers plasma levels of apolipoprotein (a) and lipoprotein (a) in transgenic mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1611–21.

Nandakumar R, et al. Effects of mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B100 antisense, on lipoprotein (a) metabolism in healthy subjects. J Lipid Res. 2018;59:2397–402.

Viney NJ, et al. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting apolipoprotein(a) in people with raised lipoprotein(a): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trials. Lancet. 2016;388:2239–53.

Tsimikas S, et al. Antisense therapy targeting apolipoprotein(a): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 study. Lancet. 2015;386:1472–83.

Akcea Therapeutics, Inc. AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx advances as leading pharmaceutical company exercises option to license. Akcea Therapeutics, Inc. 2019. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2019/02/25/1741203/0/en/AKCEA-APO-a-LRx-Advances-as-Leading-Pharmaceutical-Company-Exercises-Option-to-License.html. Accessed 4/12/2022.

HORIZON- A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial assessing the impact of lipoprotein (a) lowering with pelacarsen (TQJ230) on major cardiovascular events in patients with established cardiovascular disease (CVD). healthcare.utah.edu. https://healthcare.utah.edu/clinicaltrials/trial.php?id=FP00023345. Accessed 4/12/2022.

Tsimikas S, et al. Lipoprotein(a) reduction in persons with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:244–55.

Lim GB. Novel siRNA reduces plasma lipoprotein(a) levels. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19:147.

Korneva VA, Kuznetsova TY, Julius U. Modern approaches to lower lipoprotein(a) concentrations and consequences for cardiovascular diseases. Biomedicines. 2021;9.

Koren MJ, et al. Abstract 13951: Safety, tolerability and efficacy of single-dose Amg 890, a novel Sirna targeting Lp(a), in healthy subjects and subjects with elevated Lp(a). Circulation. 2020;142:A13951–A13951.

Kunzmann K. What’s next for lipoprotein(a) lowering agent SLN360. HCPLive https://www.hcplive.com/view/next-for-lipoprotein-a-lowering-agent-sln360. 2022.

APOLLO: Short interfering RNA shows promise for reducing lipoprotein(a). American College of Cardiology https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2022/04/02/13/22/Sun-8am-APOLLO-acc-2022. Accessed 4/12/2022. The ongoing phase 1 clinical trial APOLLO is examining the effect of another siRNA, SLN360 on lowering Lp(a) levels. A single dose (300 or 600 mg) of SLN360 has been shown to produce a maximum of 96 and 98% dose reduction respectively in Lp(a) levels. The drug produces a lasting reduction of 71–81% at five months after the treatment compared to baseline Lp(a) values.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Neeja Patel, Nikita Mittal, and Parnia Abolhassan Choubdar, MD declare they have no conflict of interest. Pam R Taub, MD is a consultant for Novartis and Amgen outside the submitted work.

Human and Animal Rights Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Lipid

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, N., Mittal, N., Choubdar, P.A. et al. Lipoprotein(a)—When to Screen and How to Treat. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 16, 111–120 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-022-00698-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-022-00698-8