Abstract

Emerging adulthood is a developmental period marked by numerous life transitions, leading emerging adults to be susceptible to distress and related psychological risks. The current study investigated the effects of socially prescribed perfectionism and parental autonomy support on psychological stress among emerging adults. We implemented a two-wave longitudinal design spanning a six-month period and latent moderation structural equations, based on data collected from 220 South Korean emerging adults (103 males, aged from 21 to 31 years). Our findings indicated that socially prescribed perfectionism predicted longitudinal increases in perceived stress, whereas parental autonomy support did not. Moderation analysis revealed that for those with high socially prescribed perfectionism, more parental autonomy support was related to greater increases in perceived stress. The results suggested that the effect of parental autonomy support may not be universally beneficial to children’s psychological distress. Rather, the effect might vary depending on cultural context and children’s individual differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Emerging adulthood is proposed as a distinct developmental period from the adolescence and young adulthood that commonly occurs between the late teens and mid-to-late 20s (see Arnett, 2004). The age period is especially important in that it sets the stage for consistent development as emerging adults start to make choices and engage in activities that have great influence on their later lives (Zarrett & Eccles, 2006). Arnett (2004) explained that emerging adulthood has five dominant features: identity exploration, instability, self-focus, feeling in-between, and possibilities.

Although its characteristics imply improvement and growth, emerging adulthood is also a challenging transition period. Unsuccessful transition during emerging adulthood is related to greater levels of stress (Barlett et al., 2020), leading emerging adults to demonstrate the highest rates of depression among all age groups (Reed-Fitzke, 2020). Indeed, transitioning through emerging adulthood can pose risks to well-being, and during the current COVID-19 pandemic, normative changes could be compounded by related stressors, including restrictions on socialization or the shrinking job market. Emerging adults likely have a more frustrating experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has affected their thrust toward independence by disrupting educational and occupational opportunities (Kujawa et al., 2020). Individuals in their early 20s have reported increased levels of perceived stress during the pandemic than before (Shanahan et al., 2020). The literature suggests that emerging adulthood can definitely elicit stress for some.

Meanwhile, Arnett (2012b, p. 240) stated that South Korea is an “intriguing and under-researched” country with respect to emerging adulthood. Challenges that South Korean emerging adults face are similar to or even harsher than those from Western countries. South Korea is one of the most highly educated countries, with 69.8% of people aged 25 to 34 years having completed higher education (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2020). Meanwhile, the youth unemployment rate is on the rise in South Korea, whereas the average unemployment rate of OECD countries decreased in the past decade (Korea Economic Research Institute, 2020). Consequently, South Korean emerging adults face greater struggles as their school-to-work transition has become more difficult and delayed.

Given that emerging adulthood is a developmental period that involves many stressors, investigation on the factors that influence emerging adults’ stress would be important. Specifically, studies on how individual differences, including personality and culture, influence stress would expand the current understanding of the psychological difficulties of emerging adults. We incorporated socially prescribed perfectionism and autonomy-supportive parenting to examine their effects on the perceived stress level among emerging adults in South Korea.

Among personality traits, socially prescribed perfectionism is a factor that can lead to stress vulnerability during emerging adulthood. Perfectionism is a multidimensional personality trait that is characterized by setting unrealistically high standards, striving for flawlessness, and evaluating the self critically (Frost et al., 1990; Slaney et al., 2001). Hewitt and Flett (1991) contended that perfectionism has both intra- and interpersonal components and introduced three dimensions of perfectionism: self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism. Self-oriented perfectionism involves setting high standards and striving for perfection for oneself while other-oriented perfectionism involves having excessively high expectations on others (Hewitt & Flett, 1991). Socially prescribed perfectionism includes people’s perception that their significant others have excessive and unrealistic standards for them, evaluate them critically, and push them to be perfect (Hewitt & Flett, 1991).

The present research focused on socially prescribed perfectionism because of the diminishing effect of striving to be perfect for others on emerging adults’ increased need for autonomy. The stress generation model of perfectionism (Hewitt & Flett, 2002) illustrates that people who set unrealistically high goals (i.e., perfectionism) are prone to encounter more stress because of the stressful circumstances created by such goal setting. They are more likely to interpret minor difficulties as major stressors and to anticipate future occasions as distressing, leading them to be susceptible to depression. Meta-analytical findings have provided supporting evidence. Smith et al. (2016) showed that socially prescribed perfectionism predicts longitudinal changes in depression. Stress has also been found to mediate this relation (Smith et al., 2020). Emerging adulthood is a self-focused time in that individuals usually have the fewest social roles and obligations to others, which gives them the autonomy to run their own lives (Arnett et al., 2014). Individuals with agency to make decisions and to define and pursue their goals independently adjust better in emerging adulthood (Lamborn & Groh, 2009). As such, emerging adults with socially prescribed perfectionism may have difficulty exercising their autonomy because they are externally motivated (e.g., Chang et al., 2016) and not familiar with making decisions and pursuing goals by themselves. Thus, life transitions during emerging adulthood, a period for gaining and exercising autonomy, can be especially troubling for young adults who have the trait of socially prescribed perfectionism.

The cultural values of South Korea can add more perfectionistic pressure. Eastern societies emphasize interpersonal relationships, and people tend to define themselves in reference to their relationships (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Indeed, East Asian cultural values has been related to perfectionism (Methikalam et al., 2015). Interdependence, for example, can develop the perception that achievement and failure are not only about oneself but also about significant others, worsening the negative effect of perfectionism on depression (Yoon & Lau, 2008). Socially prescribed perfectionistic emerging adults in South Korea, where focus is given to relationships and responsibilities to significant others, are more likely to experience distress because they feel compelled to set and pursue important developmental goals that fulfill others’ unrealistically high expectations.

Although early adolescence is considered a key period for the development of perfectionism (e.g., Damian et al., 2017; Flett et al., 2002), focusing on young adults in terms of perfectionism and its consequence is also important considering the substantial differences in experiences and outcomes (Flett et al., 2014). The current study also acknowledges the importance of perfectionism in emerging adults as the trait is consolidated and manifested in the period. Rather than investigating antecedents, our study aimed to examine the moderating role (i.e., autonomy supportive parenting) that can change the effect of perfectionism on stress level of emerging adults.

Autonomy refers to a sense of initiative, volition, or willingness in one’s behavior (Ryan & Deci, 2008, 2020). Providing autonomy to emerging adults is of importance considering their developmental needs (Hayes & Turner, 2021). Although emerging adults become more independent from their families compared with their adolescence, parents continue to be a source of autonomy support. Families provide financial and emotional support, and maintaining good relationships with the family is crucial in emerging adulthood (Zarrett & Eccles, 2006). However, although autonomy-supportive parenting is generally regarded as a universally beneficial type of parenting behavior (e.g., Lan et al., 2019), the interpretation of autonomy support may vary depending on individuals’ culture and personality. For example, in Asian American families, expressions and meaning of parental autonomy support can differ in that Asian American parents’ value interdependence, relatedness, and maintaining harmony, which can be contradictory to autonomy (Benito-Gomez et al., 2020). Similarly, a study that investigated the function of autonomy in a collectivistic culture reported that independent decision making has no significant relation with subjective well-being and basic psychological need satisfaction (Chen et al., 2013). A study with Indian participants found that autonomy-supportive instructions are less effective for motivation compared with obligation-oriented instructions (Tripathi et al., 2018). Altogether, the positive aspects of autonomy defined from the Western perspective may not always be applicable to other cultures whose members value interdependence. Korean culture, which is based on collectivism, could also have a different interpretation of parental autonomy support. A study in South Korea suggested that emerging adults perceive greater filial responsibility when receiving financial support from their parents (Hwang & Kim, 2016). Lee and Solheim (2018) also pointed out that South Korean emerging adults may have difficulty gaining autonomy if they are too tied on their parents. Thus, autonomy-supportive parenting in the context of Korean culture that values familial interdependence may operate differently from that in Western culture.

Likewise, autonomy support from parents may be detrimental to South Koreans with a high level of socially prescribed perfectionism. Research has shown that the development of maladaptive perfectionism is a product of the parenting styles of inconsistent approval, strict control, and high expectation (Enns et al., 2002; Hibbard & Walton, 2014; McCraine & Bass, 1984). That is, maladaptive perfectionism develops when individuals receive parental approval only when they satisfy the high expectations of parents. The clamor for positive feedback from parents can be detrimental for their sons and daughters in that they tend to receive negative and inaccurate feedback. Given that emerging adults with socially prescribed perfectionism may be eager to receive feedback from parents, parents’ autonomy support given to them can be perceived as lacking direction and lead to confusion.

With the increased uncertainty in the global economy and amid unexpected events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, emerging adults, who are already characterized by instability and pervasive changes (Arnett, 2004, 2012a), may respond with significant distress during their transition (Germani et al., 2020). Elevated stress in emerging adults is especially problematic because this period is considered a critical point to the later development of mental illness and substance abuse (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the factors associated with emerging adults’ stress. Specifically, we predicted that socially prescribed perfectionism would predict the increase in perceived stress after six months (hypothesis 1) and that parental autonomy support would strengthen the relation between socially prescribed perfectionism and perceived stress (hypothesis 2).

Method

Participants

The data used in the current study were drawn from a longitudinal school-to-work transition study. Emerging adults in South Korea responded to an online questionnaire at an interval of six months. We recruited the participants by posting advertisements on social media communities that emerging adults widely used. The first data collection (T1) was conducted in April 2020, and the second data (T2) was collected in November 2020 during the COIVD-19 pandemic. Participants who completed the questionnaire at T1 and T2 in the transition study were included in the analysis. The number of participants at T1 was 354, and, among them, 220 participants completed the questionnaire at T2. Thus, the final sample consisted of 220 emerging adults (103 males, 46.8%) aged 21 to 31 years (M = 25.38, SD = 1.81). Among them, 116 were students (52.7%, including undergraduate and graduate students), 94 were job-seekers (42.7%), and 10 were workers (4.5%). Data were collected after receiving approval from the institutional review board of one university in South Korea. Participants received a gift card worth USD 4.50 at each time point.

Measures

Socially Prescribed Perfectionism

We adopted the brief measure of perfectionism used in Cox et al. (2002) to measure socially prescribed perfectionism. The original scale was developed by Hewitt and Flett (1991). Han (1993) translated the measure to Korean. The current study selected items used in the brief measure of perfectionism (Cox et al., 2002) from Han (1993). The participants completed five items that were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (e.g., “Although they may not say it, other people get very upset with me when I slip up”). The coefficient alpha was .85 in Cox et al. (2002) and .70 in the current study.

Parental Autonomy Support

To measure parental autonomy support, we adopted the tool used by Moon (2006) and originally developed by Hardre and Reeve (2003). The current study used only the eight items on parental autonomy support. The items were scored on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (e.g., “My parents give me chances to choose” and “My parents try to understand how I see things before they suggest to me how they would handle a particular situation”). Internal consistency was .87 in Moon (2006) and .89 in the present study.

Perceived Stress

To measure perceived stress, we used the five-item subscale on negative perception from the Korean version of the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983; Park & Seo, 2010). An example item is “How often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?” Items were rated from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very frequently). The coefficient alpha was .77 in Park and Seo (2010) and .86 at T1 and .84 at T2 in the present study.

Data Analysis

In advance to the main analysis, we prepared the descriptive statistics. Subsequently, we applied the latent moderated structural equations method to investigate interaction effects, following the steps of Maslowsky et al. (2015). First, we estimated the measurement model. Parcels were constructed for the variable consisting of more than 5 items (i.e., parental autonomy support). Parceling is a common technique in structural equation model (see Little et al., 2013), and 8 items of parental autonomy support were ranked according to their factor loading and then distributed sequentially across three parcels. Model fit was evaluated using the chi-squared test (x2), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). RMSEA and SRMR values less than .08 were taken to show a reasonable fit, and TLI and CFI values exceeding .90 were taken to reflect acceptable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Second, we estimated the structural models. In Model 1, perceived stress at T2 was predicted by socially prescribed perfectionism and parental autonomy support at T1, controlling for perceived stress at T1. In Model 2, we added the latent interaction between socially prescribed perfectionism and parental autonomy support to Model 1. We used log-likelihood ratio test to compare the fit of Models 1 and 2. Specifically, we compared the D statistic calculated by using the log-likelihood ratios of Models 1 and 2 with the χ2distribution (with df = 1). The more parsimonious Model 1 showed a significant loss in fit compared with Model 2, and we interpreted Model 2 to represent a better fit with respect to the interaction effect of socially prescribed perfectionism and autonomy-supportive parenting on perceived stress. Throughout the analyses, we implemented maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors because of the small rate of missing values in our dataset (<1%). Mplus 7.3 was used.

Results

Preliminary analyses revealed no violation of assumption for utilizing structural equation modeling for further analyses. The descriptive statistics and bivariate correlation between variables are shown in Table 1. Socially prescribed perfectionism at T1 was positively correlated with perceived stress at both T1 and T2. Parental autonomy support at T1 was negatively correlated with perceived stress at both time points as well as with socially prescribed perfectionism.

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis to establish a measurement model prior to structural model testing. In the measurement model, each indicator was constrained to load on its corresponding latent variable. In addition, this model allowed the same items measuring perceived stress at baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) to be correlated. This model provided acceptable fit statistics (χ2(124) = 214.498, p < .001, RMSEA = .058 [.044, .070], CFI = .940, TLI = .926, SRMR = .063). This model served as a baseline for further structural equation analyses.

After establishing the measurement model, we estimated and tested two structural models (without and with the latent interaction term between socially prescribed perfectionism and parental autonomy support), applying the latent moderated structural equations with a log-likelihood ratio test (see Maslowsky et al., 2015). Model 1, with perceived stress at T2 predicted by socially prescribed perfectionism and parental autonomy support at T1, and controlling for baseline perceived stress at T1, provided a fit identical to the baseline measurement model with a log-likelihood of −4630.33. In this model, socially prescribed perfectionism at T1 significantly predicted perceived stress at T2 after accounting for baseline stress level (β = .214, p < .05). Meanwhile, the path from parental autonomy support at T1 to perceived stress at T2 was nonsignificant (β = .083, p = .213). Model 2 which included the latent interaction term revealed a significant interaction effect (β = .154, p < .05) and a log-likelihood of −4627.91, while main effects of socially prescribed perfectionism (β = .175, p = .077) and parental autonomy support at T1 were nonsignificant (β = .077, p = .247). A test statistic for a log-likelihood ratio test is calculated as follows:

D = −2[(log-likelihood for Model 1) - (log-likelihood for Model 2)].

This value is known to have an approximate χ2 distribution and may be used for a difference test between the models. The value for our analyses was 4.84 and could be compared to χ2 distribution using df = 1. Thus, Model 1 represented a significant loss in fit relative to the more complex Model 2 (χ2(1) = 4.84, p < .05). Therefore, Model 2 was retained as the best fitting model that reflected the possible interaction effect between socially prescribed perfectionism and parental autonomy support.

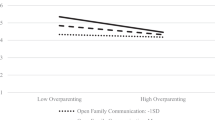

We conducted a simple slope analysis to visualize the interaction (Fig. 1). The results indicated that when emerging adults received an average level of parental autonomy support, their perceived stress level increased after a six-month period as a function of socially prescribed perfectionism. This detrimental effect of socially prescribed perfectionism became weaker, if not nonsignificant, when combined with a low level of parental autonomy support. In contrast, the effect of socially prescribed perfectionism on perceived stress became much stronger when accompanied by a high level of parental autonomy support. Alternatively, these results could be interpreted in terms of the level of socially prescribed perfectionism. On the one hand, for emerging adults with low socially prescribed perfectionism, parental autonomy support predicted the decreased level of perceived stress. For those with high socially prescribed perfectionism, on the other hand, parental autonomy support predicted the increased the level of perceived stress.

Discussion

Given the myriad stressors encountered by emerging adults, such as academic, social, and career-related difficulties (Zahniser & Conley, 2018), we aimed to elucidate what would exacerbate or mitigate their level of stress. Therefore, our study examined the effect of socially prescribed perfectionism and autonomy-supportive parenting on perceived stress among South Korean emerging adults. Our results showed the elevated risk for psychological distress during emerging adulthood, and that socially prescribed perfectionism contributed to the increased perception of stress. In addition, the effect of autonomy-supportive parenting, which is presumed to be beneficial to emerging adults’ adaptive functioning and well-being, might depend on individual differences, such as culture and personality.

Our first hypothesis was that socially prescribed perfectionism, as a personality trait, would exacerbate emerging adults’ perceived stress. When different sources of stressors accumulate, the magnitude of perceived stress often escalates. However, individual differences may play a role when interpreting and experiencing stressors. As hypothesized, socially prescribed perfectionism predicted increases in perceived stress in a six-month period, after accounting for baseline perceived stress. That is, the perception that others demand perfection and that being perfect is a way of being worthy of love and respect would operate as an inherent vulnerability, as well as adds to the situational stressors encountered by emerging adults. During emerging adulthood, individuals are expected to achieve various developmental goals, such as college entrance and graduation, landing the first potentially long-term job, finding a life partner, starting a new family, and so on. In pursuing these goals, socially prescribed perfectionists would be overly burdened as they believe that they would not be loved or respected by others if they fail to be perfect. Based on this belief, they would think and behave in ways that generate stress (Hewitt & Flett, 2002). For instance, while others may consider their failure of job applications as inevitable consequences of a pandemic-related recession, socially prescribed perfectionists may deem those failures as a result of their own imperfection and experience reduced self-worth (Hill et al., 2011), which could lead to excessive rumination and self-criticism and, in turn, increased stress perception (Randles et al., 2010).

The stress generation process of socially prescribed perfectionists might be intensified in some collectivistic cultures. Although the parent–child relationship is a major source of development of perfectionism (Damian et al., 2013), parents are not the only source of perfectionistic pressure. Perfectionistic individuals may perceive various others as imposing perfectionistic standards toward them. Given that interdependence serves as a cultural norm in collectivistic societies, such as South Korea (Yoon & Lau, 2008), the sources of perfectionistic pressure may be more divergent in interdependent cultures than in independent ones. A study showed that friends, peers, and partners, apart from parents and teachers, were significant sources of perfectionistic pressure among Asian American university students, whereas only parents and teachers were significant sources for European American counterparts (Perera & Chang, 2015). The greater number of sources of perfectionistic pressure suggests a higher likelihood for Asian socially prescribed perfectionists’ self-worth to be threatened. Moreover, the social perfectionistic demands perceived by socially prescribed perfectionists may not be imagined or falsely perceived but, to a small extent, legitimately stem from other-oriented perfectionists in their social network (Smith et al., 2017). Therefore, when applying interventions targeting the socio-cognitive aspect of socially prescribed perfectionism to perfectionists from collectivistic cultures, a more sophisticated approach should be adopted that considers divergent sources of perfectionistic pressure in one’s social network, (e.g., Egan et al., 2016).

Although emerging adulthood is a period of seeking individuation from parents, parents still exert a huge influence on their emerging adults’ adjustment and functioning (Shulman et al., 2015), especially for socially prescribed perfectionists (Perera & Chang, 2015). Therefore, we also predicted that autonomy-supportive parenting behavior, a form of social support during emerging adults’ identity exploration and pursuit of subjectivity, would moderate the effect of socially prescribed perfectionism on changes in distress level. Specifically, although autonomy support is generally perceived as a positive predictor of adjustment and well-being, we predicted that autonomy supportive parenting would not be as beneficial in East Asian cultures as it is considered in Western cultures, and may even be harmful when combined with emerging adults’ perfectionistic trait.

Our results indicated that autonomy-supportive parenting was not a meaningful predictor of perceived stress after accounting for the effect of socially prescribed perfectionism. A similar nonsignificant relation between parental autonomy support and university students’ stress perception was also found (Simon, 2021). According to self-determination theory and relevant Western literature, autonomy-supportive parenting is beneficial because it satisfies children’s basic psychological needs and sense of volition (e.g., Joussemet et al., 2008). However, the effects of parenting, or children’s appraisal of parenting, may depend on many moderating variables, such as culture and personality, thereby raising doubts on the claims about the universally adaptive role of parental autonomy support (Soenens et al., 2015). Because parents’ actual behaviors affect emerging adults’ (mal)adaptive reactions through emerging adults’ appraisal of those behaviors, parental involvement in decision making that may be considered “too much” by some emerging adults could be interpreted as an important source of social support for others (Wolf et al., 2009). Similarly, while the so-called helicopter parenting, characterized by over-involvement, overprotectiveness, and over-control (Segrin et al., 2012), is found to be detrimental to Western emerging adults’ psychological adjustment and well-being (LeMoyne & Buchanan, 2011; Schiffrin et al., 2014), it is not related to decreased psychological well-being in South Korean counterparts (Kwon et al., 2016). In this vein, South Korean emerging adults may appraise parental behaviors, which are theoretically labeled as autonomy supportive, as not beneficial, compared with their Western counterparts.

Our analysis further revealed that parental autonomy support moderated the effect of socially prescribed perfectionism on perceived stress. For South Korean emerging adults who perceived a low level of parental autonomy support, the detrimental effect of socially prescribed perfectionism on perceived stress became nonsignificant. In contrast, for those who perceived a high level of autonomy support, the effect of socially prescribed perfectionism became strengthened. The results supported the position that emphasizes contextual and individual differences in investigating the effects of parental behavior (Patall et al., 2008; Soenens et al., 2015). Socially prescribed perfectionists do not strive to meet their personal perfectionistic standards; they endeavor to attain the perfectionistic standards that they believe others impose on them. Socially prescribed perfectionists may be socialized to expect low choice decisiveness and to follow socially imposed goals, leading them to constantly fear making mistakes and being rejected by others. If one expects high parental involvement via projection of parents’ standards and conditional regard, then a higher level of autonomy support received from parents might be confusing and generate more stress. This scenario might be especially true when one is in emerging adulthood, during which one should confront an increasing number of choices. For example, when emerging adults perceive parents’ perspective taking, a typical form of autonomy granting behavior, as being vague or inconsistent expectations, then they may perceive their parents as having confused values or lacking in confidence (Assor, 2011). This phenomenon might exacerbate the socially prescribed perfectionist’s intolerance toward ambiguity (Yiend et al., 2011).

In addition, autonomy-supportive parenting behaviors, even when not expressed in forceful ways, might put additive social pressure on perfectionistic emerging adults. For instance, when encouraged by parents to make career-related choices and decisions that reflect their true values and interests, socially prescribed perfectionistic individuals could be compelled by their dysfunctional beliefs (e.g., “my parents are expecting me to be perfect”) to think that they should make a perfect choice, leading them to become more distressed and indecisive (Kang et al., 2020).

Overall, the current results suggested that autonomy-supportive parenting would have different effects based on emerging adults’ contextual and individual differences. These differences might affect emerging adults’ interpretation of parental behavior. Therefore, for optimal communication with emerging adults, parents should carefully consider their sons and daughters’ personality when identifying important cultural and familial values and actual needs. Some studies have reported the effect of psychoeducational and group-based interventions in changing parenting behaviors (e.g., Jordans et al., 2013; Pedersen et al., 2019). However, interventions that focus on enhancing parents’ understanding of their emerging adults by including not only parents but also emerging adults would be much more effective, given that parenting behaviors are interpreted through emerging adults’ individual variability.

The current study was not without limitations. First, we relied on self-rating instruments to measure the study variables. Although self-reports provide valuable information and emerging adults’ perceptions may be more “real” than reality itself, other sources of information, such as parental ratings on their parenting behaviors or physiological data related to stress responses, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relations studied here. Second, although we assumed that our samples predominantly embraced collectivistic cultural values, the drastic socioeconomic transformation and societal modernization in South Korea might yield individual variations in cultural self-construal (e.g., Cheng et al., 2011). Moreover, research suggests that the millennial generation is more individualistic than other generations (Greenfield, 2013). Hence, future research would profit from directly measuring individual self-construal or conducting a cross-cultural comparison to reveal the role of culture more thoroughly. Third, the current findings may be limited to the specific time span under study (six months). Future researchers may investigate whether our findings are replicated with shorter or longer time spans.

Despite these limitations, our findings expand the current understanding of emerging adults’ stress responses in relation to their own personality trait (i.e., socially prescribed perfectionism) and parents’ behaviors (i.e., autonomy support) within the context of South Korean culture. Although the literature largely underscores the importance of parenting in emerging adults’ psychological adjustment and well-being, most of the research has focused on parenting in childhood and adolescence. The discussion on the transition of children to adulthood is rather marginalized (Gower & Dowling, 2008). However, the parent–child relationship remains an integral part of adult children’s psychological adjustment and psychosocial functioning (Shulman et al., 2015). Therefore, researchers in diverse cultural contexts should carefully consider the possible cultural bias of age-bound developmental theory (Hendry & Kloep, 2007) and put effort toward further elucidating emerging adults’ individual differences and parent–child relationships.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2012a). Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A cultural approach (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Arnett, J. J. (2012b). New horizons in research on emerging and young adulthood. In A. Booth, S. L. Brown, N. S. Landale, W. D. Manning, & S. M. McHale (Eds.), Early adulthood in a family context (pp. 231–244). Springer.

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7

Assor, A. (2011). Autonomous moral motivation: Consequences, socializing antecedents, and the unique role of integrated moral principles. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), The social psychology of morality: Exploring the causes of good and evil (pp. 239–255). American Psychological Association.

Barlett, C. P., Barlett, N. D., & Chalk, H. M. (2020). Transitioning through emerging adulthood and physical health implications. Emerging Adulthood, 8(4), 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818814642

Benito-Gomez, M., Williams, K. N., McCurdy, A., & Fletcher, A. C. (2020). Autonomy-supportive parenting in adolescence: Cultural variability in the contemporary United States. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 12(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12362

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage.

Chang, E., Lee, A., Byeon, E., Seong, H., & Lee, S. M. (2016). The mediating effect of motivational types in the relationship between perfectionism and academic burnout. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.010

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Soenens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2013). Autonomy in family decision making for Chinese adolescents: Disentangling the dual meaning of autonomy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(7), 1184–1209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113480038

Cheng, C., Jose, P. E., Sheldon, K. M., Singelis, T. M., Cheung, M. W., Tiliouine, H., ... & Sims, C. (2011). Sociocultural differences in self-construal and subjective well-being: A test of four cultural models. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(5), 832–855. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110381117

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Clara, I. P. (2002). The multidimensional structure of perfectionism in clinically distressed and college student samples. Psychological Assessment, 14(3), 365–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.14.3.365

Damian, L. E., Stoeber, J., Negru, O., & Băban, A. (2013). On the development of perfectionism in adolescence: Perceived parental expectations predict longitudinalincreases in socially prescribed perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(6), 688–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.021.

Damian, L. E., Stoeber, J., Negru-Subtirica, O., & Băban, A. (2017). On the development of perfectionism: The longitudinal role of academic achievement and academic efficacy. Journal of Personality, 85(4), 565–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12261

Egan, S. J., Wade, T. D., Shafran, R., & Antony, M. M. (2016). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of perfectionism. Guilford.

Enns, M. W., Cox, B. J., & Clara, I. (2002). Adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism: Developmental origins and association with depression proneness. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(6), 921–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00202-1

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Oliver, J. M., & Macdonald, S. (2002). Perfectionism in children and their parents: A developmental analysis. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 89–132). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-004

Flett, G. L., Besser, A., & Hewitt, P. L. (2014). Perfectionism and interpersonal orientations in depression: An analysis of validation seeking and rejection sensitivity in a community sample of young adults. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 77(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2014.77.1.67

Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172967

Germani, A., Buratta, L., Delvecchio, E., & Mazzeschi, C. (2020). Emerging adults and COVID-19: The role of individualism-collectivism on perceived risks and psychological maladjustment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103497

Gower, M., & Dowling, E. (2008). Parenting adult children–invisible ties that bind? Journal of Family Therapy, 30(4), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2008.00438.x

Greenfield, P. M. (2013). The changing psychology of culture from 1800 through 2000. Psychological Science, 24(9), 1722–1731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613479387

Han, K. Y. (1993). Multidimensional perfectionism: Concept, measurement and relevance to maladjustment (unpublished doctoral dissertation). Korea University, Seoul.

Hardre, P. L., & Reeve, J. (2003). A motivational model of rural students’ intentions to persist in, versus drop out of, high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.347

Hayes, K. N., & Turner, L. A. (2021). The relation of helicopter parenting to maladaptive perfectionism in emerging adults. Journal of Family Issues. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X21993194.

Hendry, L. B., & Kloep, M. (2007). Conceptualizing emerging adulthood: Inspecting the emperor’s new clothes? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00017.x

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–470. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2002). Perfectionism and stress processes in psychopathology. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 255–284). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-011

Hibbard, D. R., & Walton, G. E. (2014). Exploring the development of perfectionism: The influence of parenting style and gender. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(2), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.2.269

Hill, A. P., Hall, H. K., & Appleton, P. R. (2011). The relationship between multidimensional perfectionism and contingencies of self-worth. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(2), 238–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.036

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hwang, W., & Kim, I. (2016). Parental financial support and filial responsibility in emerging adulthood: A comparative study between the United States and South Korea. Journal of Youth Studies, 19(10), 1401–1418. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1171833

Jordans, M. J., Toi, W. A., Ndayisaba, A., & Komproe, I. H. (2013). A controlled evaluation of a brief parenting psychoeducation intervention in Burundi. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(11), 1851–1859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0630-6

Joussemet, M., Landry, R., & Koestner, R. (2008). A self-determination theory perspective on parenting. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012754

Kang, M., Lee, J., & Lee, A. (2020). The effects of college students’ perfectionism on career stress and indecision: Self-esteem and coping styles as moderating variables. Asia Pacific Education Review, 21(2), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-019-09609-w

Korea Economic Research Institute. (2020). Youth unemployment rate, OECD 4.4%p decrease, Korea 0.9%p increase for 10 years [hwp file]. Retrieved July 20, 2021 from http://www.keri.org/web/www/news_02?p_p_id=EXT_BBS&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&_EXT_BBS_struts_action=%2Fext%2Fbbs%2Fview_message&_EXT_BBS_messageId=356040

Kujawa, A., Green, H., Compas, B. E., Dickey, L., & Pegg, S. (2020). Exposure to COVID-19 pandemic stress: Associations with depression and anxiety in emerging adults in the United States. Depression and Anxiety, 37(12), 1280–1288. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23109

Kwon, K. A., Yoo, G., & Bingham, G. E. (2016). Helicopter parenting in emerging adulthood: Support or barrier for Korean college students’ psychological adjustment? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(1), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0195-6

Lamborn, S. D., & Groh, K. (2009). A four-part model of autonomy during emerging adulthood: Associations with adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(5), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025409338440

Lan, X., Ma, C., & Radin, R. (2019). Parental autonomy support and psychological well-being in Tibetan and Han emerging adults: A serial multiple mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 621. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00621

Lee, J., & Solheim, C. A. (2018). Associations between familism and psychological adjustment among Korean emerging adults: Underlying processes. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 49(4), 409–435. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.49.4.409

LeMoyne, T., & Buchanan, T. (2011). Does “hovering” matter? Helicopter parenting and its effect on well-being. Sociological Spectrum, 31(4), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2011.574038

Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., & Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods, 18(3), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033266

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Maslowsky, J., Jager, J., & Hemken, D. (2015). Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414552301

McCraine, E. W., & Bass, J. D. (1984). Childhood family antecedents of dependency and self-criticism: Implications for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.93.1.3

Methikalam, B., Wang, K. T., Slaney, R. B., & Yeung, J. G. (2015). Asian values, personal and family perfectionism, and mental health among Asian Indians in the United States. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6(3), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000023

Moon, E. (2006). A structural analysis of the social-motivational variables influencing adolescents’ school dropout behavior. The Research of Educational Psychology, 20(2), 405–423.

OECD. (2020). Education at a glance 2020: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en

Park, J. O., & Seo, Y. S. (2010). Validation of the perceived stress scale (PSS) on samples of Korean university students. The Korean Journal of Psychology: General, 29(3), 611–629.

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). The effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes: A meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 270–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.270

Pedersen, G. A., Smallegange, E., Coetzee, A., Hartog, K., Turner, J., Jordans, M. J., & Brown, F. L. (2019). A systematic review of the evidence for family and parenting interventions in low-and middle-income countries: Child and youth mental health outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(8), 2036–2055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01399-4

Perera, M. J., & Chang, E. C. (2015). Ethnic variations between Asian and European Americans in interpersonal sources of socially prescribed perfectionism: It’s not just about parents! Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036175

Randles, D., Flett, G. L., Nash, K. A., McGregor, I. D., & Hewitt, P. L. (2010). Dimensions of perfectionism, behavioral inhibition, and rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(2), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.002

Reed-Fitzke, K. (2020). The role of self-concepts in emerging adult depression: A systematic research synthesis. Journal of Adult Development, 27(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-018-09324-7

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). A self-determination theory approach to psychotherapy: The motivational basis for effective change. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012753

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Schiffrin, H. H., Liss, M., Miles-McLean, H., Geary, K. A., Erchull, M. J., & Tashner, T. (2014). Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(3), 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9716-3

Segrin, C., Woszidlo, A., Givertz, M., Bauer, A., & Taylor Murphy, M. (2012). The association between overparenting, parent-child communication, and entitlement and adaptive traits in adult children. Family Relations, 61(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00689.x

Shanahan, L., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Murray, A. L., Nivette, A., Hepp, U., Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. (2020). Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000241X

Shulman, S., Barr, T., Livneh, Y., Nurmi, J. E., Vasalampi, K., & Pratt, M. (2015). Career pursuit pathways among emerging adult men and women: Psychosocial correlates and precursors. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414533222

Simon, P. D. (2021). Parent autonomy support as moderator: Testing the expanded perfectionism social disconnection model. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110401

Slaney, R. B., Rice, K. G., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., & Ashby, J. S. (2001). The revised almost perfect scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34(3), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2002.12069030

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Rnic, K., Saklofske, D. H., Enns, M., & Gralnick, T. (2016). Are perfectionism dimensions vulnerability factors for depressive symptoms after controlling for neuroticism? A meta-analysis of 10 longitudinal studies. European Journal of Personality, 30(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2053

Smith, M. M., Speth, T. A., Sherry, S. B., Saklofske, D. H., Stewart, S. H., & Glowacka, M. (2017). Is socially prescribed perfectionism veridical? A new take on the stressfulness of perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 110, 115–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.031

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Vidovic, V., Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2020). Why does perfectionism confer risk for depressive symptoms? A meta-analytic test of the mediating role of stress and social disconnection. Journal of Research in Personality, 86, 103954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103954

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Van Petegem, S. (2015). Let us not throw out the baby with the bathwater: Applying the principle of universalism without uniformity to autonomy-supportive and controlling parenting. Child Development Perspectives, 9(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12103

Tripathi, R., Cervone, D., & Savani, K. (2018). Are the motivational effects of autonomy-supportive conditions universal? Contrasting results among Indians and Americans. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(9), 1287–1301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218764663

Wolf, D. S. S., Sax, L., & Harper, C. E. (2009). Parental engagement and contact in the academic lives of college students. NASPA Journal, 46(2), 325–358. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.6044

Yiend, J., Savulich, G., Coughtrey, A., & Shafran, R. (2011). Biased interpretation in perfectionism and its modification. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(12), 892–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.10.004

Yoon, J., & Lau, A. S. (2008). Maladaptive perfectionism and depressive symptoms among Asian American college students: Contributions of interdependence and parental relations. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14(2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.92

Zahniser, E., & Conley, C. S. (2018). Interactions of emotion regulation and perceived stress in predicting emerging adults’ subsequent internalizing symptoms. Motivation and Emotion, 42(5), 763–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9696-0

Zarrett, N., & Eccles, J. (2006). The passage to adulthood: Challenges of late adolescence. New Directions for Youth Development, 111, 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.179

Availability of Data

The dataset analyzed for the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A2A01043871).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict no interest that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Korea University Institutional Review Board (KUIRB-2020-0315-01).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seong, H., Lee, S. & Lee, S.M. Is autonomy-supportive parenting universally beneficial? Combined effect of socially prescribed perfectionism and parental autonomy support on stress in emerging adults in South Korea. Curr Psychol 42, 13182–13191 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02520-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02520-x