Abstract

In this study, I examine the effects of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion on the labor supply decisions of non-disabled, low-educated, childless adults ages 50-64. I employ a triple-differences (DDD) methodology, exploiting variation in individuals’ health insurance status and the expansion decisions of states. I find that with Medicaid expansion, insured workers without retirement health insurance (RHI) decreased full-time work by 7.06 percentage points relative to those with RHI and those without any employer-sponsored coverage at all. Among those no longer working full-time, 82 percent transitioned to complete retirement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that health insurance exchanges, the other signature measures in the ACA, provide premium tax credits to eligible people to help them purchase coverage through the market places. Income requirement for premium tax credits eligibility ranges from 138% to 400% of FPL in states that expanded Medicaid, while tax credit eligibility ranges from 100% to 400% of FPL in non-expansion states. The ACA’s Medicaid expansion and health insurance exchange were implemented at the same year (2014). However, isolating the effects of Medicaid expansion from health insurance exchanges is not a concern, as the marketplace program is implemented uniformly across all states.

There are studies that analyze the effects of ACA on labor force participation among the working-age population rather than focusing on the sample most likely to be observed in retirement lock, older pre-Medicare eligible individuals (ages 50-64). They find little to no effect on labor force participation and small declines in hours worked Kaestner et al (2017); Gooptu et al (2016); Moriya et al (2016); Leung and Mas (2018).

The Rand HRS file is derived from all waves of the HRS. It provides a cleaned and user-friendly version of the original data and produced by the RAND Center for the Study of Aging, with funding and support from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Social Security Administration (SSA)

Coverage in retirement derived from the variable RwHERET in the Rand HRS 1992-2016.

To assign individuals that have a missing value for the question on retiree insurance for any reason either in the treatment or control groups, I apply the following strategy: If over time individuals retire, it can be inferred whether they have RHI or not by observing whether they are covered by their or spouse’s employer plan when they retire. If individuals are retired and covered by their or spouse’s employer-sponsored health insurance, I allocate those in the control group.

Individuals who have missing years of education information are dropped.

The full-time work indicator equals 1 if the individual works full-time and 0 if she/he works part-time, is retired, partly retired, unemployed, and not in the labor force.

The results are robust to including the period after re-entry to full-time work (For details, see Appendix Table 15)

Note that the employer mandate, which requires employers with 50 or more full-time workers to provide health insurance or face penalties, was implemented under the ACA in 2015. This policy might affect the composition of working hours. For example, an employer might limit the number of hours employees can work or replace full-time workers with part-time. However, the potential changes in working hours will not threaten my identification because the employer mandate started to be effective nationwide, and the changes would cancel out between expansion and non-expansion states as long as their responses are not significantly distinct. To examine whether there is a differential response in expansion states versus non-expansion states, I compare working hours across expansion and non-expansion states before and after the employer mandate. The result shows that there is no significant difference between expansion and non-expansion states (For details, see Appendix Table 19).

Despite the fact that both Hawaii (HI) and Arizona (AZ) expanded Medicaid eligibility earlier, I did not remove them because they temporarily suspended it and then reinstated it to the level required by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2014. In the year 2000, Arizona expanded coverage for childless adults up to 100% of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL), but starting in July 2011, enrollment for adults was capped. Likewise, Hawaii covered coverage for childless adults up to 100% FPL through its QUEST Medicaid managed care waiver program, but enrollment was closed for certain groups in 2012. The results are similar if Arizona and Hawaii are excluded (For details, see Appendix Table 21).

Additionally, I remove Wisconsin from the main sample and the sample that includes both early and late expansion states, and re-estimate the equation (1). The results are qualitatively in line with the main findings (For details, see Appendix Table 20).

The results are robust when the interaction of the Treat dummy variable with the full set of age and year fixed effects are excluded from the model (For details, see Appendix Table 23)

Individuals who skipped the HRS question regarding pension plans due to not having current jobs are identified as having no pension plan. In addition, eighty-four individuals in my sample did not respond to the pension questions even though they have a current job. Those individuals are also identified as having no pension plan. Excluding them from the sample provides similar results to the main finding.

A small number cluster (generally less than 50) may result in having too small standard errors and over-rejection of the null hypothesis (Cameron and Miller (2015); Donald and Lang (2007); McCaffrey and Bell (2006)). In my case, the number of state clusters is 37, so I apply block-bootstrapped standard errors by household and state groups based on 700 replications to alleviate this concern.

The results are robust when the sample is constrained to the year from 2010 to 2016.

The part-time work indicator equals 1 if the individual works part-time or is partly retired and 0 if she/he works full-time, is retired, unemployed, and not in the labor force. Similarly, the any work indicator equals 1 if the individual works full-time or part-time or is partly retired and 0 if she/he is retired, unemployed,or not in the labor force. Self-employment indicators are constructed based on individuals’ self-report. The HRS survey asks respondents whether they are self-employed or work for someone else. Respondents’ possible answers are either self-employed or working for someone else. There are some cases where answers are missing because respondents refuse to answer or do not know. Therefore, the sample size is smaller when the dependent variable is self-employed.

Earnings are very right-skewed, so I top code earnings at the ninety-fifth percentile among full-time workers ($100,000). In addition, I exclude observations with over 70 usual hours of work per week due to misreporting is highly likely.

The new equation is as in following :

\(Y_{ist}= \alpha _{0} + \beta _{0} (Treat_{ist}\times Expansion_{st})+\beta _{1}Expansion_{st}+ \beta _{2}Treat_{ist}+\beta _{3} X_{ist} + \gamma _{t}\times Treat_{ist} + \alpha _{a} Treat_{ist} + \alpha _{a}+\gamma _{t} + \mu _{i} + \phi _{st}+\epsilon _{ist}\)

The Federal Poverty Level (FPL) changes with the number of individuals in the household, so does the Medicaid income eligibility threshold. I chose an annual household income of $50K as an upper bound of the annual household income level because that 138% of FPL for a household with seven people is 50,687$ for contiguous states and the District of Columbia in 2016. Note that monetary variables in the sample are inflated to 2016 prices.

References

Alemayehu B, Warner KE (2004) The lifetime distribution of health care costs. Health services research 39(3):627–642

Aslim EG (2019) The relationship between health insurance and early retirement: Evidence from the affordable care act. Eastern Economic Journal 45(1):112–140

Ayyagari P (2019) Health insurance and early retirement plans: Evidence from the affordable care act. American Journal of Health Economics 5(4):533–560

Blau DM, Gilleskie DB (2001) Retiree health insurance and the labor force behavior of older men in the 1990s. Review of Economics and Statistics 83(1):64–80

Boyle MA, Lahey JN (2010) Health insurance and the labor supply decisions of older workers: Evidence from a us department of veterans affairs expansion. Journal of public economics94(7-8):467–478

Bradley CJ, Sabik LM (2019) Medicaid expansions and labor supply among low-income childless adults: Evidence from 2000 to 2013. International Journal of Health Economics and Management 19(3):235–272

Callaway B, SantÁnna PH (2021) Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics 225(2):200–230

Cameron AC, Miller DL (2015) A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of human resources 50(2):317–372

Correia S (2015) Singletons, cluster-robust standard errors and fixed effects: A bad mix. Duke University, Technical Note

Dague L, DeLeire T, Leininger L (2017) The effect of public insurance coverage for childless adults on labor supply. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9(2):124–54

De Chaisemartin C, d’Haultfoeuille X (2020) Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. American Economic Review 110(9):2964–96

Dillender M, Heinrich CJ, Houseman S (2022) Effects of the affordable care act on part-time employment early evidence. Journal of Human Resources 57(4):1394–1423

Donald SG, Lang K (2007) Inference with difference-in-differences and other panel data. The review of Economics and Statistics 89(2):221–233

Duggan M, Goda GS, Li G (2021) The effects of the affordable care act on the near elderly: Evidence for health insurance coverage and labor market outcomes. Tax Policy and the Economy 35(1):179–223

Elsby MW, Hobijn B, Sahin A (2010) The labor market in the great recession. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research

Fitzpatrick MD (2014) Retiree health insurance for public school employees: Does it affect retirement? Journal of health economics 38:88–98

French E, Jones JB (2011) The effects of health insurance and self-insurance on retirement behavior. Econometrica 79(3):693–732

Garthwaite C, Gross T, Notowidigdo MJ (2014) Public health insurance, labor supply, and employment lock. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(2):653–696

Goodman-Bacon A (2021) Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. Journal of Econometrics 225(2):254–277

Gooptu A, Moriyas AS, Simon KI, Sommers BD (2016) Medicaid expansion did not result in significant employment changes or job reductions in 2014. Health affairs 35(1):111–118

Gruber J (1994) The incidence of mandated maternity benefits. The American economic review pages 622–641

Gruber J, Madrian BC (1994) Health insurance and job mobility: The effects of public policy on job-lock. ILR Review 48(1):86–102

Gruber J, Madrian BC (1995) Health-insurance availability and the retirement decision. The American Economic Review 85(4):938–948

Gustman AL, Steinmeier TL (1994) Employer-provided health insurance and retirement behavior. ILR Review 48(1):124–140

Gustman AL, Steinmeier TL, Tabatabai N (2019) The Affordable Care Act as retiree health insurance: Implications for retirement and social security claiming. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 18(3):415–449

Kaestner R, Garrett B, Chen J, Gangopadhyaya A, Fleming C (2017) Effects of aca medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and labor supply. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 36(3):608–642

Kapur K, Rogowski J (2011) How does health insurance affect the retirement behavior of women? INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization. Provision, and Financing 48(1):51–67

Leiserson GQ (2013) Essays on the economics of public sector retirement programs. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Leung P, Mas A (2018) Employment effects of the affordable care act medicaid expansions. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 57(2):206–234

Levy H, Buchmueller TC, Nikpay S (2018) Health reform and retirement. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 73(4):713–722

Lumsdaine RL, Stock JH, Wise DA (1994) Pension plan provisions and retirement: men and women, medicare, and models. In:Studies in the Economics of Aging, pages 183–222. University of Chicago Press

Madrian BC (1994) Employment-based health insurance and job mobility: Is there evidence of job-lock? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 109(1):27–54

Marton J, Woodbury SA (2013) Retiree health benefits as deferred compensation: evidence from the health and retirement study. Public Finance Review 41(1):64–91

McCaffrey DF, Bell RM (2006) Improved hypothesis testing for coefficients in generalized estimating equations with small samples of clusters. Statistics in Medicine 25(23):4081–4098

Moriya AS, Selden TM, Simon KI (2016) Little change seen in part-time employment as a result of the affordable care act. Health Affairs 35(1):119–123

Mulligan CB (2020) The employer penalty, voluntary compliance, and the size distribution of firms: Evidence from a survey of small businesses. Tax Policy and the Economy 34(1):139–171

Nyce S, Schieber SJ, Shoven JB, Slavov SN, Wise DA (2013) Does retiree health insurance encourage early retirement? Journal of Public Economics 104:40–51

Robinson C, Clark R (2010) Retiree health insurance and disengagement from a career job. Journal of Labor Research 31(3):247–262

Shoven JB, Slavov SN (2014) The role of retiree health insurance in the early retirement of public sector employees. Journal of health economics 38:99–108

Strumpf E (2010) Employer-sponsored health insurance for early retirees: impacts on retirement, health, and health care. International journal of health care finance and economics 10(2):105–147

Sun L, Abraham S (2021) Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Econometrics 225(2):175–199

Wettstein G (2020) Retirement lock and prescription drug insurance: Evidence from medicare part d. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12(1):389–417

Wood K (2019) Health insurance reform and retirement: Evidence from the affordable care act. Health economics 28(12):1462–1475

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Confict of Interest

The Author declares that there is no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I thank Scott Adams, Scott Drewianka, John S. Heywood, UWM Micro Workshop participants, and two anonymous referees for their insight and suggestions.

Appendix A: Data Appendix

Appendix A: Data Appendix

The Rand HRS data from 2010-2016 includes 42,052 individuals and 168,208 person-year observations. Restricting the sample to non-disabled, low-educated, childless adults ages 50-64 yields a final sample of 4,682 individuals, 3,984 households, and 8,269 person-year observations. Table 14 illustrates information on sample loss due to each restriction.

Appendix B: Including the Period After Re-Entry to Full-time Work

In the main analysis, I exclude periods after re-entry to full time work because the triple-difference technique utilized in my empirical model is designed to reflect movement in one direction-departing from full-time work. However, this might lead selection bias if the ACA’s Medicaid expansion influence post-retirement labor supply decision. I re-estimate the equation (1) by including all observations in the analysis to test the robustness of results.

Table 15 presents triple-difference estimates that include all observations. Table 15 confirms that the results hold when using all observations in the analysis.

Appendix C: The Impact of the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion on Total Household Out-of-Pocket Medical Spending

To analyze the effects of Medicaid expansion on the household out-of-pocket medical spending of low-educated, childless individuals without any ESHI, I utilize a log-linear model and quantile estimation. Table 16 shows the effects of Medicaid expansion on the log of total household out-of-pocket medical spending. Similarly, Table 17 illustrates the change in expenditure at every fifth quantile of the distribution of total household out-of-pocket medical spending associated with Medicaid expansion.

The HRS data provide information regarding individuals’ and their spouses’ total out-of-pocket medical spending. Total household out-of-pocket total medical spending is constructed by summing individuals’ and their spouses’ total out-of-pocket medical spending.

Tables 16 and 17 illustrate that Medicaid expansion did not affect household out-of-pocket medical spending of low-educated, childless individuals who do not have health insurance from their employer or their spouse.

Appendix D: The Impact of the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion on ESHI and RHI

Table 18 illustrates the effects of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion on employer-sponsored health insurance (Column 1) and retiree coverage (Column 2).

Panel A of Table 18, illustrates the results for the full sample; panel B for those who are low-educated, childless ages 50-64.

Appendix E: The impact of Employer Mandate on Working Hours

Table 19 illustrates data on working hours by expansion, non-expansion states, and time periods. Working hour counts the number of hours per week a person works at her/his main and second job. The years 2010,2012, and 2014 are defined as the periods before the employer mandate, while the year 2016 counts as the period after the employer mandate. Panel A of Table 19 illustrates the results for the full sample; panel B for those who are low-educated, childless ages 50-64.

The difference-in-differences estimates in the third row of panel A and B indicates that there is no significant difference in the response of expansion and non-expansion states regarding workings hours to the employer mandate.

Appendix F: Excluding Wisconsin from the Sample

Prior to 2014, the Medicaid program in Wisconsin was limited to children, pregnant women, and parents with dependent children. Wisconsin did not expand Medicaid under the ACA; however, in 2014, it extended its Medicaid program to all individuals with income up to 100% FPL. As a result, Wisconsin is the only non-expansion state without a coverage gap.Footnote 23 Therefore, I treat Wisconsin as an experimental state so far.

To test the robustness of my findings, I remove Wisconsin from the sample and re-estimate the equation (1). Since a large number of childless adults, approximately 99,000, became newly eligible for Wisconsin Medicaid with its recent expansion, defining Wisconsin as a non-expansion state might be misleading; therefore, for robustness check, I exclude Wisconsin instead of defining it as a non-expansion state.

Table 20 presents triple-differences estimates that exclude Wisconsin. Columns 1-3 of Table 20 present the result for the sample excluding early and late expansion states, while columns 3-5 display the result for the sample, including early and late expansion states. Table 20 confirms that the qualitative results hold using the sample excluding Wisconsin. These findings indicate -5.55 percentage points decline in full-time work for the sample excluding early and late expansion states, and -5.36 percentage points decline in full-time work for the sample, including early and late expansion states.

Appendix G: Excluding Arizona and Hawaii from the Sample

In the main analysis, I exclude early and late expansion states for the purpose of clear analysis. However, I did not drop Hawaii and Arizona as early expansion states because they closed their enrollment and were reinstated at the ACA level in 2014. Though Hawaii is quite small, Arizona’s eligibility changes might confound the results given its size and large retirement communities.

To test the robustness of my findings, I remove Arizona and Hawaii from the sample and re-estimate equation (1). Table 21 presents triple-differences estimate that exclude Arizona and Hawaii. The results are similar to the main finding.

Appendix H: The Main Result with Coefficient Estimates of Individual Controls

Table 22 display the triple-differences estimates of the effects of the ACA Medicaid expansion on full-time work. Individual controls include an indicator for being married, divorced, or widowed; indicator for being enrolled in a pension plan from the current job; and total wealth.

Appendix I: Alternative Identification

In the main model, I include a full set of age and year fixed effects along with their interaction with the Treat dummy variable. The reason for adding interaction terms in the model is to capture the heterogeneity of being in the treatment group over time and across age groups, which allows me to account for the non-linear and time-varying nature of being in the treatment group. However, given the relatively small sample size, including a full set of age, year fixed effect, and their interaction with the Treat dummy variable plus individual fixed effect and state-specific time trends might result in a saturated model. To alleviate this concern, I re-estimate equation (1) without

interaction of the Treat dummy variable with age and year fixed effects. Table 23 illustrates that the results are consistent with the main findings when the interaction terms are not excluded from the model.

Appendix J: Difference-in-Differences Estimates the Impact of the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion on Full-time Work

Table 24 shows the effects of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion on full-time work. I restrict the sample to low-educated, childless individuals ages 50-64. Note that the expansion and non-expansion states I used in this analysis are the same as the ones I used in the main analysis (See Table 3).

Appendix K: Figures

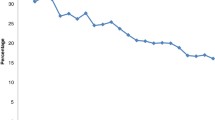

Figure 1 above represents the share of low-educated and low-income individuals aged 50-64 in the years 2010-2016 in each insurance category displayed in a legend. Low education is defined as having a high school degree or less, and low income is defined as having an annual household income equal to or less than $50K.

RHI represents individuals who have retiree coverage. No ESHI consists of those who do not have any employer-sponsored health insurance at all. Medicaid comprises individuals who have Medicaid coverage before the expansion. Finally, ESHI without RHI includes individuals with employer-sponsored health insurance but no retiree coverage. Note that observations with missing data regarding retiree health coverage are dropped.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Onal, S.O. Does the ACA Medicaid Expansion Encourage Labor Market Exits of Older Workers?. J Labor Res 44, 56–93 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-023-09342-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-023-09342-9