Abstract

How sex is negotiated has reached greater interest because a lack of consent is considered to be a risk factor for sexual violence. However, the mechanisms underlying sexual consent still remain unexplored. The purpose of the present study was to examine the link between rape-supportive attitudes and objectification, as experienced by women and perpetrated by men, in the context of specific domains relevant to the establishment and negotiation of sexual consent, i.e., attitudes, beliefs and behaviors. The sample comprised 1682 participants (21.5% male, 78.5% female) aged 18–66 years (M = 23.41; SD = 6.96). In women, negotiation of consent was predicted both directly and indirectly by being sexually objectified by men, rape attitudes playing a mediating role. Women who were objectified reported lower efficacy with respect to asking for consent and considered explicit establishment of consent as important. In men, only the perpetration of unwanted sexual advances predicted how they negotiate consent, in which rape attitudes played a mediating role (indicating a maladaptive pattern of negotiation). Our findings could be useful for the design and implementation of intervention programs that address both victims and perpetrators of violence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Negotiation of sexual consent has recently become a widely studied area due to the MeToo wave. Global data reveal that around 30% of women aged between 15 and 49 years have suffered physical or sexual violence at some point in their lives (WHO, 2018). According to the Macrosurvey on Violence against Women 2019 in Spain (Spanish Ministry of Equality, 2020), 13.7% (corresponding to almost 3 million women) have suffered sexual violence throughout their lives. It is worth mentioning that the person responsible for sexual violence is usually someone the survivor knows, such as a friend or current of former intimate partner, among others (CDC, 2022a). Regarding gender, sexual violence in Spanish women has been perpetrated by a man in 99.6% of cases (Spanish Ministry of Equality, 2020). Therefore, sexual violence is a type of gender-based violence, with adherence to traditional norms of gender roles being an individual risk factor and societal norms that support male superiority and sexual entitlement, societal norms that maintain women’s inferiority and sexual submissiveness, and weak laws and policies related to sexual violence and gender equity being societal factors (CDC, 2022b).

Although sexual consent has proven relevant for comprehending sexual violence, recent studies have barely paid attention to it (Beres, 2007; Muehlenhard et al., 2016). Previous studies have analysed the relationship between attitudes towards rape and sexual consent. For example, Camp et al. (2018) found that women, compared to men, take more positive attitudes towards explicit consent, and they are less likely to blame other women who, having drunk alcohol, are victims of sexual assault. In men, hypermasculine attitudes and acceptance of the rape myth have been related to unfavourable attitudes towards communication about sexual consent (Shafer et al., 2018). It should be noted that supportive attitudes towards rape are related to violent or aggressive behaviours (Moyano et al., 2017). In their study, they showed that male aggressors often endorse more attitudes towards rape than non-aggressors. Therefore, maintaining a culture that supports certain ideas associated with the perpetuation of sexual violence behaviours reduces the responsibility for seeking sexual consent (Argiero et al., 2010; Kilimnik & Humphreys, 2018).

Another salient aspect in current societies is women’s sexual objectification (Calogero, 2013; UN Women, 2019). According to Noll and Fredrickson (1998), “objectification” is defined as the belief that being a woman implies being treated as a sexual object or a body that must be evaluated or looked at. In countries where a more marked traditional gender role is maintained, there is a greater objectification and a higher risk of aggression or violence (Eaton & Matamala, 2014; Hayes et al., 2016; Klement et al., 2017). Following Sáez-Díaz (2016), as a dominant group, men could perceive sexualized women as a threat to their social status because women could increase their power by sexuality. As a consequence of this threat, hostility and male dominance could be higher (Infanger et al., 2014). Moreover, men who are more exposed to sexualized women also accept more myths about rape, and myths of sexual abuse, gender stereotypes and interpersonal violence (Sáez-Díaz, 2016). Furthermore, undesired explicit advances that are supported by sexual scripts would lead to greater invisibility and refusal of consent. So although there is evidence to indicate a relation between greater sexual objectification and a higher degree of aggression, to date there are no studies that have directly addressed the relation between sexual objectification and sexual consent. Hence, the need to analyze whether women’s objectification, including both that carried out by the man (e.g., “I have whistled at someone while I was walking down the street”) and that received by the woman (e.g., “I have been whistled at while I was walking down the street”), is related to the importance attached to requesting sexual consent for sexual relations (Hust et al., 2017).

To the best of our knowledge, no published studies have examined the association between sexual objectification and sexual consent, and little research has examined the relationship between objectification and sexually aggressive behaviors such as rape. For example, Rudman and Mescher (2012) used the Implicit Association Test to show that objectifying women by associating them with objects/tools correlated with men’s proclivity to rape. In addition, in their experimental study, Loughnan et al. (2013) showed that sexual objectification was associated with higher levels of victim blaming and lower levels of moral concern, similar to the finding of Bernard et al. (2015) that sexual objectification decreases the blame placed on rapists. A study using the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification (ISOS-P) reported that sexual objectification increased women´s fear of rape (Szymanski et al., 2021). Finally, sexual objectification predicted sexual violence, with alcohol being a mediating variable (Gervais et al., 2014b). However, no previous studies have analyzed the roles of objectification and rape-supportive attitudes in sexual consent using an integrated model.

The Current Study

Considering all of the above, the goal of the present study was to examine the link between sexual objectification, as experienced by women and perpetrated by men, and certain domains of sexual consent; it is posited that rape-supportive attitudes likely play a significant mediating role in this relationship. This study uses a multidimensional measure of sexual consent, i.e., the Sexual Consent Scale-Revised (SCS-R; Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010). This scale provides information regarding attitudes, beliefs and behaviors related to sexual consent.

Due to the lack of previous research linking the variables examined herein with specific domains of sexual consent, we formulated the following research questions:

- RQ1:

-

Is sexual objectification, as suffered by women and perpetrated by men, associated with the attitude, belief and behavior domains of sexual consent?

- RQ2:

-

Are rape-supportive attitudes associated with the attitude, belief and behavior domains of sexual consent?

- RQ3:

-

Do rape-supportive attitudes mediate the associations between objectification and the attitude, belief and behavior domains of sexual consent?

Method

Participants

This is a cross-sectional study. A non-probabilistic (convenience) sample was used, due to the facility of recruitment based on the target population and easy verification of will to participate. The eligibility criteria included: (1) older than 18 years; (2) self-identify as heterosexual; (3) have Spanish nationality. Initially, data from 1718 Spanish men and women were recruited, and those of 38 individuals were eliminated because information was missing in more than 25% of the survey. Therefore, the final sample was made up of 1680 (21.5% male, 78.5% female). They had Spanish nationality and their age range was 18–66 years old (M = 23.41; SD = 6.96). Most had a university degree (60.2%). About 58.1% were in a relationship at the time. They were all heterosexual. The mean age of their first sexual intercourse was 16.51 (SD = 2.91) and the mean number of sexual partners was 5.95 (SD = 9.79).

Instruments

A first section included items related to information about socio-demographic variables: gender (masculine, feminine, other), age, education, whether they were in a relationship and sexual orientation (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual), by using the Kinsey Scale of Sexual Orientation (Kinsey et al., 1948) that ranges from 0 (exclusively heterosexual) to 6 (exclusively homosexual), age when first sexual intercourse occurred and number of sexual partners.

Sexual Consent

For this study, we validated the SCS-R (Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010), that measures an individual's beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors with respect to how sexual consent should be and is negotiated between sexual partners. The SCS-R consists of 39 items and a Likert-type response scale with seven alternatives (1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree). The scale is composed of five dimensions related to how sexual consent should be and is negotiated between sexual partner: Factor 1: (Lack of) perceived behavioral control (i.e., how much behavioral control over sexual consent negotiations participants perceive), Factor 2: Positive attitude toward establishing consent (i.e., favorable evaluations and beliefs about establishing consent before beginning sexual activities), Factor 3: Indirect behavioral approach to consent (i.e., the use of indirect, nonverbal ways of to negotiate sexual consent), Factor 4: Sexual consent norms (i.e., beliefs about the norms that regulate sexual consent negotiations), and Factor 5: Awareness and discussion (i.e., the amount of awareness or general discussions participants have about sexual consent). This scale has been validated in heterosexual university students with adequate psychometric properties (Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010).

The translation and adaptation of the SCS-R were carried out by a group of researchers consisting of bilingual psychologists and experts in psychometrics and evaluation of sexual attitudes. The authors of the original version gave their permission for the adaptation and they participated in this process. We considered previous research to make the translation and adaptation (Elosua et al., 2014; Muñiz et al., 2013), along with the standards of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), the American Psychological Association (APA) and the National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME) (2015). The initial translation was reviewed by a bilingual expert and one of the study researchers, and then a bilingual expert did a back translation. We made changes to avoid literal translations after comparing the back translation to the original. Subsequently, we conducted a pilot study with 20 individuals with similar socio-demographic characteristics to the participants in the present research, who had to indicate whether they correctly understood each item. If they found any ambiguous term of expression, they had to indicate it and explain why. As all the items achieved an 85% agreement about their clarity, no changes were made.

We conducted a CFA with the method used ML. The goodness-of-fit indices supported a four-factor structure, in which factor 5 (Awareness of Consent) was deleted. The final Spanish version of the SCS-R comprised 26 items that accounted for 41.4% of variance. The correlations between Factor 2 with Factor 1 (r = − 0.38), with Factor 3 (r = − 0.18) and with Factor 4 (r = − 0.20) were negative, while the correlations between Factor 1 and Factor 3 (r = 0.18), Factor 3 and 4 (r = 0.43) and Factor 1 and 4 (r = 0.25) were positive. Cronbach’s alpha values were: Factor 1: (Lack of) Perceived Behavioural Control (α = 0.85); Factor 2: Positive Attitude Towards Establishing Consent (α = 0.85); Factor 3: Indirect Behavioural Approach to Consent (α = 0.66); Factor 4: Sexual Consent Norms (α = 0.70). More detailed information of the psychometric properties of the scale can be provided upon request. The final 26-item Spanish version is included in “Appendix”.

Rape Attitudes

The Spanish validated version of the Rape Supportive Attitude Scale (RSAS; Lottes, 1991) was used (Sierra et al., 2007). This scale comprises 20 items that evaluate beliefs in rape. Some statements are as follows: “Rape is the expression of an uncontrollable desire for sex”. Its response scale is a Likert-type with five alternatives (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The scale is univariate with adequate reliability and validity in the Spanish population (Sierra et al., 2007). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha value was 0.84.

Objectification Suffered by Women

We used the victim version of the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale-Women´s version (ISOS-W). The first version of the scale was developed by Kozee et al. (2007) and it was validated in Spanish women by Lozano et al. (2015). It is a 15-item scale that assesses the degree to which the woman is “objectified” or treated as a sexual object. It has two dimensions: Body Evaluation and Unwanted Explicit Sexual Advances. For each respective dimension, women are asked to respond to the following statements: “How often have you noticed someone staring at your breasts when you are talking to them?” and “How often has someone grabbed or pinched one of your private body areas against your will?”. Its response scale is Likert-type with five alternatives (1 = never to 5 = always). Both, the original version and the version validated in Spain have adequate psychometric properties, reliability and evidence of validity. In the present study, Cronbach´s alpha value was respectively 0.92 and 0.80 for Body Evaluation and Unwanted Explicit Sexual Advances.

Objectification Perpetrated by Men

The Perpetration Version of the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale-Perpetration Version (ISOS-P) for men was developed by Kozee et al. (2007) and validated by Gervais et al. (2014a) to evaluate sexual objectification behaviours perpetrated by men. In this case, the 15 items are written in the form of “carrying out these behaviours” (e.g., “How often have you whistled at someone while walking down the street?”). For the Spanish validation that has been recently conducted (Sánchez-Fuentes et al., in press), the scores are well distributed, similar to the original version, on a three-dimensional scale: Body Gazes, Body Comments and Unwanted Explicit Sexual Advances. Therefore, men are asked to answer to some of the following items respectively to the described dimensions: “How often have you leered at someone´s body?”, “How often have you made a rude, sexual remark about someone´s body?” and “How often have you touched or fondled someone against her/his will?”. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha values were 0.70, 0.72 and 0.85, respectively for Body Gazes, Comments and Unwanted Explicit Sexual Advances.

Procedure

We disseminated the online survey via a link that was distributed on social networks and by the news service of the universities that participated in this study. When the participants clicked on the link, it allowed them access to the study information and informed consent, which contained the study purpose and its selection criteria. Then they were asked if they wished to participate. They had to indicate “yes” to go to all the questionnaires. Questionnaires had to be fulfilled once. Therefore, no code or identification system was required of the participants, which favored their anonymity. By considering their answer to the “gender” question, they were lead to a different questionnaire at the end of the survey, that is, for women the final questionnaire presented was the ISOS-W and for men, the final questionnaire presented was the ISOS-P.

In addition, questionnaires were not disseminated until the research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the three universities involved in the study; that is, the University of Jaén, Granada and Salamanca.

Data Analysis

To examine whether the variables followed normal distributions, we calculated the kurtosis and skewness of the main variables. The results showed that all main variables followed a normal distribution [i.e., skewness < 2 and kurtosis < 7.0 (Hancock et al., 2010)]. Second, we conducted a correlation analysis. Third, we tested the hypothesized model in AMOS 25.0 using Maximum Likelihood Estimation and bootstrapping with 5000 replicates. Two models were tested differentiating by gender, in which dimensions from objectification were set as predictor variables, rape attitudes as the mediator and all four domains of sexual consent as outcome variables.

To assess how well the model fit the data, we used the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA; < 0.08), p value for close fit (nonsignificant p value), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; > 0.95) (Brown, 2015).

Results

First, Pearson’s correlations were carried out between sexual consent domains, rape supportive attitudes and objectification. As shown in Table 1, the four SCS-R factors correlated statistically and significantly with supporting rape. In particular, lack of perceived behavioural control, indirect behavioural approach to consent and sexual consent norms correlated with more favourable attitudes towards rape, while the Positive attitude towards establishing consent factor was related to less favourable attitudes towards rape. An association was also found between the SCS-R factors and objectification. For women, body evaluation and unwanted explicit sexual advances were associated with positive attitudes towards establishing consent and negatively with indirect behavioural approach to consent and sexual consent norms. For men, having made comments about a woman's body was related to less favourable attitudes to explicitly establish consent, with more favourable attitudes not to explicitly establish consent, request consent through non-verbal language and with beliefs in consent being important only in casual relationships. Additionally, unwanted explicit sexual advances were associated with lack of perceived behavioural control and negatively with positive attitude towards establishing consent.

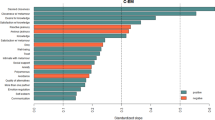

The relationship between objectification and dimensions of sexual consent was analyzed using Rape Supportive Attitudes as a mediating variable. We constructed two differentiated models: one for men that included body gazes, body comments and unwanted sexual advances as objectification dimensions, and another for women in which body evaluation and unwanted sexual advances were the objectification dimensions. Sexual consent was broken down into its four dependent variables: F1. lack of perceived behavioral control; F2. positive attitude towards establishing consent; F3. indirect behavioral approach; and F4. norms of sexual consent.

As can be seen in Fig. 1, for men, objectification was represented solely by the unwanted sexual advances dimension, which indirectly predicted sexual consent via the mediating variable of rape supportive attitudes at p < 0.001 (0.39***). Specifically, the correlation coefficients between three sexual consent factors were as follows: F1. lack of perceived behavioral control, 0.36***; F2. Positive attitude towards establishing consent, − 0.34***; and F4. Norms of sexual consent, 0.20***. The model fit indices were as follows: χ2 = 5.651; RMSEA = 0.050; PCLOSE = 0.415; and CFI = 0.987. These values indicated a good fit of the data to the model.

A second mediational analysis was carried out for a model based on women. As can be seen in Fig. 2, objectification of women predicted sexual consent; the correlation coefficients for the four dimensions of sexual consent were as follows: F1. Lack of perceived behavioral control (r = 0.19***); F2. Positive attitude towards establishing consent (r = 0.30***); F3. Indirect behavioral approach (r = − 0.24***); and F4. Norms of sexual consent, (r = − 0.28***). The inverse relationships for F3 and F4 are notable. In addition to the direct relationship, rape supportive attitudes also played a mediating role, and increased the coefficients for F1. Lack of perceived behavioral control (r = 0.38***) and F2. Positive attitude towards establishing consent (r = − 0.34***). On the other hand, objectification, as denoted by Body Evaluation, in women predicted sexual consent only indirectly through rape supportive attitudes. The fit indices indicated robustness of the model, where [χ2 = 6.482; RMSEA = 0.022; PCCLOSE = 0.944; CFI = 0.998]. These values demonstrate the theoretical and practical validity of the model for characterizing the relationships of interest.

Discussion

The present study examined the relationship between sexual objectification and specific domains of sexual consent, and the mediating role of rape-supportive attitudes. Our findings indicate that, in women, all four domains of sexual consent, that is, (Lack of) Perceived Behavioural Control, Positive Attitude towards Establishing Consent, Indirect Behavioral Approach and Norms of Sexual Consent, were predicted by both forms of objectification, while for Unwanted Sexual Advances and Body Evaluation rape attitudes played a mediating role. In men, only perpetration of Unwanted Sexual Advances predicted three domains of consent, i.e., (Lack of) Perceived Behavioural Control, Positive Attitude towards Establishing Consent, and Norms of Sexual Consent, with a mediating role being played by rape attitudes. Our findings are consistent with previous studies in which the perception of sexual assaults being justifiable increases as exposure to female objectification leads to men dehumanizing women (Awasthi, 2017). In addition, a positive attitude towards rape is associated with the perception that establishing sexual consent is less important (Warren et al., 2015). More specifically, acceptance of myths about rape has been reported as a predictor of reduced adherence to sexual consent, i.e., less behavioral intention to obtain it (Fritz-Williams, 2022).

In comparison to previous research, our findings go a step further by analyzing several domains of sexual consent, namely attitudes, beliefs and specific behaviors. When examining the associations between objectification and attitudes towards rape with sexual consent, we found that women who had experienced more objectification (Body evaluation and Unwanted explicit sexual advances) adopted more positive attitudes towards explicitly establishing sexual consent, but did not agree that sexual consent should be requested through body language (Indirect behavioural approach). Women who indicated that they had been objectified through Body Evaluation also indicated that consent was important in any context or situation (Norms of sexual consent), while women who indicated that they had suffered from unwanted sexual contacts felt less able to establish sexual consent (Lack of behavioral control). On the other hand, for men, the results of our correlation analysis indicated that those who had commented on a woman's body (Body evaluation) considered that verbally requesting sexual consent could reduce the likelihood of having sex (Lack of Perceived Behavioural Control). They had less positive attitudes towards explicitly requesting consent (Positive Attitude Towards Establishing Consent), believed that sexual consent could be obtained through non-verbal behaviors (Indirect Behavioural Approach) and viewed consent as important only in certain sexual contexts (Norms of Sexual Consent). In addition, men who had touched women without their consent also considered that explicitly requesting sexual consent could reduce the likelihood of having sex (Lack of Perceived Behavioural Control), and had more negative attitudes towards requesting consent (Positive Attitude Towards Establishing Consent). This is in line with previous studies indicating that objectification is a risk factor for sexual assault, especially in countries in which traditional gender roles remain (Eaton & Matamala, 2014; Hayes et al., 2016; Klement et al., 2017); this is the case in Spain, especially among men (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2019; Moyano & Granados, 2020).

Second, in this study, attitudes more supportive of rape are associated with lower ability to ask for consent, less positive attitudes towards requesting consent, the use of more indirect strategies for obtaining consent, and certain beliefs about whether consent should be requested in certain contexts. Therefore, when attitudes, beliefs and behaviors related to consent acquisition are maladaptive, rape may be more strongly endorsed. Such beliefs lead to greater acceptance and justification of violence, where willingness to have sex is interpreted incorrectly; this contributes to a culture in which victims are blamed (Suarez & Gadalla, 2010). As concluded previously, acceptance of rape myths is associated with destructive intentions relating to consent and less ability to correctly interpret complex consent scenarios (Shafer et al., 2018), and a lack of perceived behavioral control and less positive attitudes toward establishing consent (Kilimnik & Humphreys, 2018; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., in press). Analysis of rape myths is important considering that they could be a precursor for the perpetration of violence (Adams-Curtis & Forbes, 2004; Moyano et al., 2017; Nunes et al., 2013).

The findings of our novel mediational model emphasize that women who have been objectified exhibit increased awareness of their vulnerability, which leads them to eschew attitudes that would place them at risk of further violence. In particular, women who had experienced more objectification (Body Evaluation and Unwanted Explicit Sexual Advances) perceived themselves as less capable of asking for consent. However, they have acquired more adaptive forms of managing consent; their attitudes towards establishing consent are more positive, and they consider that consent should not be signaled indirectly or through body language (Indirect Behavioural Approach). They also considered the establishment of consent to be important in all contexts and situations (Norms of Sexual Consent). This is consistent with previous studies in which sexual victims, in comparison to non-sexual victims, considered the establishment of consent important, although their ability (self-efficacy) to do so was diminished (Edison et al., 2022; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., in press). This is probably because women who have suffered sexual violence show less sexual assertiveness (Bhochhibhoya et al., 2021; Kelley et al., 2016) and are therefore less willing to ask for consent (Darden et al., 2019; Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010). Furthermore, victims indicated that they would not readily assume that consent had been granted without direct verbal communication to that effect; consent should be obtained explicitly to reduce ambiguity (Humphreys & Brousseau, 2010). Our findings also confirm previous studies in which suffering objectification increased women’s fear of rape (Szymanski et al., 2021). Experiences of sexual objectification frequently carry an implicit threat of sexual violence and undermine women’s sense of safety (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Watson et al., 2015). Therefore, such women are likely to show increased awareness of situations in which rape could take place and therefore adopt attitudes that reduce their vulnerability.

Our findings for men suggest that those who have touched women without their consent (Unwanted sexual advances) are more likely to endorse rape, and therefore to indirectly consider themselves less able to request sexual consent verbally (Lack of Perceived Behavioural Control). They hold more negative attitudes towards explicitly requesting consent (Positive Attitude Towards Establishing Consent) and tend to believe that consent should only be sought in certain situations. Therefore, objectification, and especially the performance of specific behaviors associated with unwanted contact towards women, are linked to more positive attitudes towards rape, which is a risk factor for engaging in sexual violence (via its indirect effect on sexual consent), as also shown previously (Moyano et al., 2017; Nunes et al., 2013).

Some differences were apparent in the explanatory models of consent for men and women. In men, rape attitudes clearly mediated the objectification of women and negotiation of sexual consent; in contrast, women’s experience of objectification was directly and indirectly related to sexual consent. Therefore, for women, being the target of sexual advances was both directly and indirectly (via rape attitudes) related to sexual consent, while being sexually objectified though body evaluations only exerted an effect through the mediating role of rape attitudes. This may be because, in patriarchal cultures, evaluation of women’s bodies through comments or gazes is common. Therefore, women may be used to this form of objectification such that it does not have a direct effect on how sex is negotiated, instead affecting their attitudes toward specific forms of violence. On the other hand, objectification through unwanted sexual contact is more similar to specific behaviors and acts of violence such as being grabbed, touched, fondled or sexually harassed. Interestingly, this finding supports the notion that each dimension of objectification should be considered individually, as they play roles in different stages along the continuum of sexual violence perpetration. Further research should aim to validate this view.

The present research had some limitations. First, we employed non-probabilistic sampling, so our findings cannot be generalized to the entire Spanish population. This is a common disadvantage of this recruitment method as the external validity will be limited (Andrade, 2021). Second, most of the participants were heterosexual women with a high level of education. Thus, future studies should recruit more men, sexual minorities, and a heterogeneous sample in terms of education level to allow examination of whether the relative importance of different dimensions of sexual consent varies according to socio-demographic variables (e.g., in accordance with sexual orientation and educational level). Likewise, future research should aim to verify whether the Spanish version of the SCS-R is invariant based on sex; cross-cultural studies are necessary because cross-cultural differences have been found in the SDS, for example (Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2020). In addition, validation of the scale in other countries could stimulate intercultural research and address the cultural bias present in this research field.

Our study has novel aspects; in contrast to previous studies, it analyzed several domains of sexual consent, i.e., attitudes, beliefs and specific behaviors. Our findings could inform educational practice as it relates to the culture of sexual consent. Future studies could explore whether individuals are more likely to request consent based on specific variables, and its utility as a predictor of different forms of sexual assault. Identifying risk factors for the perpetuation of sexual assaults (e.g. not explicitly requesting sexual consent) is essential for the implementation of prevention programs targeting both potential victims and perpetrators.

Data Availability

Data transparency: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Code Availability

Software application or custom code: Not applicable.

References

Adams-Curtis, L. E., & Forbes, G. B. (2004). College women’s experiences of sexual coercion: A review of cultural, perpetrator, victim, and situational variables. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 5(2), 91–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838003262331

AERA, APA, NCME. (2015). Standards for educational and psychological tests. American Educational Research Association.

Álvarez-Muelas, A., Gómez Berrocal, C., Vallejo-Medina, P., & Sierra, J. C. (2019). Invariance of Spanish version of sexual double standard scale across sex, age, and education level. Psicothema, 31, 465–474. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2019.102

Andrade, C. (2021). The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 43(1), 86–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620977000

Argiero, S. J., Dyrdahl, J. L., Fernandez, S. S., Whitney, L. E., & Woodring, R. J. (2010). A cultural perspective for understanding how campus environments perpetuate rape-supportive culture. Journal of the Student Personnel Association at Indiana University, 43, 26–40.

Awasthi, B. (2017). From attire to assault: Clothing, objectification, and de-humanization—A possible prelude to sexual violence? Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 338. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00338

Beres, M. A. (2007). ‘Spontaneous’ sexual consent: An analysis of sexual consent literature. Feminism and Psychology, 17(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353507072914

Bernard, P., Loughnan, S., Marchal, C., Godart, A., & Klein, O. (2015). The exonerating effect of sexual objectification: Sexual objectification decreases rapist blame in a stranger rape context. Sex Roles, 72(11), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0482-0

Bhochhibhoya, S., Maness, S. B., Cheney, M., & Larson, D. (2021). Risk factors for sexual violence among college students in dating relationships: An ecological approach. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15–16), 7722–7746. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519835875

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Calogero, R. M. (2013). Objects don’t object: Evidence that self-objectification disrupts women’s social activism. Psychological Science, 24, 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612452574

Camp, S. J., Sherlock-Smith, A. C., & Davies, E. L. (2018). Awareness and support: Students’ views about the prevention of sexual assault on UK campuses. Health Education, 118, 431–446. https://doi.org/10.1108/HE-02-2018-0007

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2022a). Fast facts: Preventing sexual violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/fastfact.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2022b). Risk and protective factors. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html

Darden, M. C., Ehman, A. C., Lair, E. C., & Gross, A. M. (2019). Sexual compliance: Examining the relationships among sexual want, sexual consent, and sexual assertiveness. Sexuality and Culture, 23(1), 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9551-1

Eaton, A. A., & Matamala, A. (2014). The relationship between heteronormative beliefs and verbal sexual coercion in college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1443–1457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0284-4

Edison, B., Coulter, R. W., Miller, E., Stokes, L. R., & Hill, A. V. (2022). Sexual communication and sexual consent self-efficacy among college students: Implications for sexually transmitted infection prevention. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(2), 282–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.08.012

Elosua, P., Mujika, J., Almeida, L. S., & Hermosilla, D. (2014). Procedimientos analítico-racionales en la adaptación de tests. Adaptación al español de la batería de pruebas de razonamiento [Judgmental-analytical procedures for adapting tests: Adaptation to Spanish of the Reasoning Tests Battery]. Revista Latinoamericana De Psicología, 46, 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0120-0534(14)70015-9

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Fritz-Williams, N. (2022). Yes, no, and maybe: The creation of a multidimensional scale to measure sexual consent behavioral intentions and the exploration of the role of campus sexual health messages. Doctoral thesis. Indiana University.

Gervais, S., Davidson, M., Styck, K., Canivez, G., & David, D. (2014a). Interpersonal sexual objectification scale—Perpetration version. PsycTESTS dataset.

Gervais, S. J., DiLillo, D., & McChargue, D. (2014b). Understanding the link between men’s alcohol use and sexual violence perpetration: The mediating role of sexual objectification. Psychology of Violence, 4(2), 156–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033840

Hancock, G. R., Mueller, R. O., & Stapleton, L. M. (2010). The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences. Routledge.

Hayes, R. M., Abbott, R. L., & Cook, S. (2016). It’s her fault: Student acceptance of rape myths on two college campuses. Violence against Women, 22, 1540–1555. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801216630147

Humphreys, T. P., & Brousseau, M. M. (2010). The sexual consent scale–revised: Development, reliability, and preliminary validity. Journal of Sex Research, 47, 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903151358

Hust, S. J., Rodgers, K. B., & Bayly, B. (2017). Scripting sexual consent: Internalized traditional sexual scripts and sexual consent expectancies among college students. Family Relations, 66, 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12230

Infanger, M., Rudman, L. A., & Sczesny, S. (2014). Sex as a source of power? Backlash against self-sexualizing women. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 19(1), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430214558312

Kelley, E. L., Orchowski, L. M., & Gidycz, C. A. (2016). Sexual victimization among college women: Role of sexual assertiveness and resistance variables. Psychology of Violence, 6(2), 243. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039407

Kilimnik, C. D., & Humphreys, T. P. (2018). Understanding sexual consent and nonconsensual sexual experiences in undergraduate women: The role of identification and rape myth acceptance. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 27, 195–206. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2017-0028

Kinsey, A. C., Pomery, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Kinsey scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/t17515-000

Klement, K. R., Sagarin, B. J., & Lee, E. M. (2017). Participating in a culture of consent may be associated with lower rape-supportive beliefs. The Journal of Sex Research, 54, 130–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1168353

Kozee, H. B., Tylka, T. L., Augustus-Horvath, C. L., & Denchik, A. (2007). Development and psychometric evaluation of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00351.x

Lottes, I. L. (1991). Beliefs systems: Sexuality and rape. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 4, 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v04n01_05

Loughnan, S., Pina, A., Vasquez, E. A., & Puvia, E. (2013). Sexual objectification increases rape victim blame and decreases perceived suffering. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(4), 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313485718

Lozano, L. M., Valor-Segura, I., Sáez, G., & Expósito, F. (2015). The Spanish adaptation of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale (ISOS). Psicothema, 27, 134–140. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.124

Moyano, N., & Granados, R. (2020). Consentimiento sexual, concepto y evaluación: Marco introductorio [Sexual consent, concept and assessment: An introductory framework]. In J. C. Suárez-Villegas, N. Martínez-Pérez, & P. Panarese (Eds.), Cartografía de los micromachismos: Dinámicas y violencia simbólica (pp. 423–433). Dykinson.

Moyano, N., Monge, F. S., & Sierra, J. C. (2017). Predictors of sexual aggression in adolescents: Gender dominance vs. rape supportive attitudes. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 9, 25–31.

Muehlenhard, C. L., Humphreys, T. P., Jozkowski, K. N., & Peterson, Z. D. (2016). The complexities of sexual consent among college students: A conceptual and empirical review. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 457–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1146651

Muñiz, J., Elosua, P., & Hambleton, R. (2013). Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los tests: Segunda edición [Guidelines for the translation and adaptation of tests: Second edition]. Psicothema, 25, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.24

Noll, S. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 623–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00181.x

Nunes, K. L., Hermann, C. A., & Ratcliffe, K. (2013). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward rape are associated with sexual aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(13), 2657–2675. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513487995

Rudman, L. A., & Mescher, K. (2012). Of animals and objects: Men’s implicit dehumanization of women and likelihood of sexual aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(6), 734–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212436401

Sáez-Díaz, G. (2016). Cosificación sexual: Nuevas formas de violencia contra la mujer [Sexual objectification: New forms of violence against women]. Doctoral thesis. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10481/44017

Sánchez-Fuentes, M. M., Granados, R., Parra-Barrera, S. M., & Moyano, N. (in press). The Spanish validation of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale-perpetration version (ISOS-P). Manuscript submitted for publication.

Sánchez-Fuentes, M. M., Moyano, N., Gómez-Berrocal, C., & Sierra, J. C. (2020). Invariance of the sexual double standard scale: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051569

Shafer, A., Ortiz, R. R., Thompson, B., & Huemmer, J. (2018). The role of hypermasculinity, token resistance, rape myth, and assertive sexual consent communication among college men. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62, S44–S50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.015

Sierra, J. C., Rojas, A., Ortega, V., & Ortiz, J. D. (2007). Evaluación de actitudes sexuales machistas en universitarios: Primeros datos psicométricos de las versiones españolas de la Double Standard Scale (DSS) y de la Rape Supportive Attitude Scale (RSAS) [Evaluating sexist attitudes with university students: First psychometric data of Spanish versions of the Double Standard Scale (DSS) and the Rape Supportive Attitude Scale (RSAS)]. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 7, 41–60.

Spanish Ministry of Equality. (2020). Macroencuesta de la violencia contra la mujer 2019 [Macrosurvey of violence against women 2019]. Retrieved from https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/macroencuesta2015/Macroencuesta2019/home.htm

Suarez, E., & Gadalla, T. M. (2010). Stop blaming the victim: A meta-analysis on rape myths. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(11), 2010–2035. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509354503

Szymanski, D. M., Strauss Swanson, C., & Carretta, R. F. (2021). Interpersonal sexual objectification, fear of rape, and US college women’s depression. Sex Roles, 84(11), 720–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01194-2

United Nations for Women [UN Women]. (2019). International day for the elimination of violence against women. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/es/news/stories/2019/11/press-release-international-day-for-the-elimination-of-violence-against-women

Warren, P., Swan, S., & Allen, C. T. (2015). Comprehension of sexual consent as a key factor in the perpetration of sexual aggression among college men. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 24, 897–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2015.1070232

Watson, L. B., Marszalek, J. M., Dispenza, F., & Davids, C. M. (2015). Understanding the relationships among White and African American women’s sexual objectification experiences, physical safety anxiety, and psychological distress. Sex Roles, 72(3), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0444-y

World Health Organization. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women#:~:text=Worldwide%2C%20almost%20one%20third%20(27,violence%20by%20their%20intimate%20part

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Granada/CBUA. This work was supported by the Plan Propio de Investigación y Transferencia of the University of Granada [Research and Transfer Plan of the University of Granada]; funding was provided to the fourth author in 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest is reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Spanish Version of the Sexual Consent Scale-Revised (SCS-R)

Appendix: Spanish Version of the Sexual Consent Scale-Revised (SCS-R)

Item | Item |

|---|---|

(1) I would have difficulty asking for consent because it would spoil the mood | Tendría dificultad en pedir consentimiento sexual porque eso “cortaría el rollo”* |

(2) I am worried that my partner might think I’m weird or strange if I asked for sexual consent before starting any sexual activity | Me preocupa que mi pareja pueda pensar que soy raro/a si pido consentimiento sexual antes de comenzar cualquier actividad sexual* |

(3) I would have difficulty asking for consent because it doesn’t really fit with how I like to engage in sexual activity | Sería difícil para mí pedir consentimiento sexual porque eso no se ajusta a cómo me gusta participar en la actividad sexual* |

(4) I would worry that if other people knew I asked for sexual consent before starting sexual activity, that they would think I was weird or strange | Me preocuparía que, si otras personas supieran que pido consentimiento sexual antes de iniciar la actividad sexual, pensaran que soy raro/a* |

(5) I think that verbally asking for sexual consent is awkward | Pienso que pedir consentimiento sexual de forma verbal es incómodo* |

(6) I have not asked for sexual consent (or given my consent) at times because I felt that it might backfire and I wouldn’t end up having sex | No he pedido consentimiento sexual (ni he dado mi consentimiento) porque pensé que entonces no tendría relaciones sexuales* |

(7) I believe that verbally asking for sexual consent reduces the pleasure of the encounter | Creo que pedir consentimiento sexual de forma verbal reduce el placer del encuentro* |

(8) I would have a hard time verbalizing my consent in a sexual encounter because I am too shy | Sería difícil para mí verbalizar el consentimiento en un encuentro sexual porque soy demasiado tímido/a |

(9) I feel confident that I could ask for consent from a new sexual partner [R] | No tendría inconveniente en pedirle consentimiento a una nueva pareja sexual* |

(10) I would not want to ask a partner for consent because it would remind me that I’m sexually active | No me gustaría pedirle consentimiento a una pareja porque me recordaría que soy sexualmente activo/a |

(11) I feel confident that I could ask for consent from my current partner [R] | No tendría inconveniente en pedirle consentimiento a mi pareja actual |

(12) I feel that sexual consent should always be obtained before the start of any sexual activity | Opino que el consentimiento sexual debería obtenerse siempre antes de comenzar cualquier actividad sexual* |

(13) I believe that asking for sexual consent is in my best interest because it reduces any misinterpretations that might arise | Creo que pedir consentimiento sexual es lo mejor porque reduce cualquier interpretación errónea que pueda surgir* |

(14) I think it is equally important to obtain sexual consent in all relationships regardless of whether or not they have had sex before | Pienso que es importante obtener el consentimiento sexual en todas las relaciones sexuales, indistintamente de si se han tenido o no relaciones sexuales con esa persona* |

(15) I feel that verbally asking for sexual consent should occur before proceeding with any sexual activity | Opino que pedir consentimiento sexual debería ocurrir antes de llevar a cabo cualquier actividad sexual* |

(16) When initiating sexual activity, I believe that one should always assume they do not have sexual consent | Al iniciar la actividad sexual, siempre se debería suponer que no se tiene consentimiento sexual* |

(17) I believe that it is just as necessary to obtain consent for genital fondling as it is for sexual intercourse | Creo que es tan necesario obtener consentimiento para caricias genitales como para las relaciones sexuales coitales* |

(18) Most people that I care about feel that asking for sexual consent is something I should do | La mayoría de las personas de mi círculo cercano piensan que se debe pedir el consentimiento sexual* |

(19) I think that consent should be asked before any kind of sexual behaviour, including kissing or petting | Pienso que se debe pedir consentimiento antes de cualquier tipo de comportamiento sexual, incluidos los besos o caricias* |

(20) I feel it is the responsibility of both partners to make sure sexual consent is established before sexual activity begins | Opino que es responsabilidad de ambos miembros de la pareja asegurarse de que se establezca el consentimiento sexual antes de que comience la actividad sexual* |

(21) Before making sexual advances, I think that one should assume ‘‘no’’ until there is clear indication to proceed | Antes de un acercamiento sexual, pienso que uno debería asumir "no" hasta que haya una clara indicación para proceder |

(22) Not asking for sexual consent some of the time is okay [R] | En ocasiones no pedir consentimiento sexual está bien |

(23) Typically I communicate sexual consent to my partner using nonverbal signals and body language | Por lo general, comunico el consentimiento sexual a mi pareja utilizando señales no verbales y lenguaje corporal* |

(24) Typically I communicate sexual consent to my partner using nonverbal signals and body language | Es fácil leer con precisión las señales no verbales de mi pareja actual (o la más reciente) que indican consentimiento o no consentimiento de la actividad sexual* |

(25) Typically I ask for consent by making a sexual advance and waiting for a reaction, so I know whether or not to continue | Por lo general, pido consentimiento haciendo un acercamiento sexual y esperando una reacción, para saber si continuar o no* |

(26) I don’t have to ask or give my partner sexual consent because my partner knows me well enough | No tengo que pedir ni dar mi consentimiento sexual a mi pareja porque mi pareja me conoce suficientemente bien* |

(27) I don’t have to ask or give my partner sexual consent because I have a lot of trust in my partner to ‘‘do the right thing’’ | No tengo que pedir ni dar mi consentimiento sexual a mi pareja porque tengo mucha confianza en que él/ella “hará lo correcto |

(28) I always verbally ask for consent before I initiate a sexual encounter [R] | Siempre solicito consentimiento de forma verbal antes de iniciar un encuentro sexual |

(29) I think that obtaining sexual consent is more necessary in a new relationship than in a committed relationship | Pienso que obtener consentimiento sexual es más necesario en una nueva relación que en una relación en la que exista compromiso* |

(30) I think that obtaining sexual consent is more necessary in a casual sexual encounter than in a committed relationship | Pienso que obtener consentimiento sexual es más necesario en un encuentro sexual casual que en una relación en la que exista compromiso* |

(31) I believe that the need for asking for sexual consent decreases as the length of an intimate relationship increases | Creo que la necesidad de pedir consentimiento sexual disminuye a medida que aumenta la duración de una relación de pareja* |

(32) I believe it is enough to ask for consent at the beginning of a sexual encounter | Creo que es suficiente pedir el consentimiento al comienzo de un encuentro sexual |

(33) I believe that sexual intercourse is the only sexual activity that requires explicit verbal consent | Creo que las relaciones sexuales coitales son la única actividad sexual que requiere el consentimiento verbal explícito* |

(34) I believe that partners are less likely to ask for sexual consent the longer they are in a relationship | Creo que las parejas tienen menos probabilidades de pedir consentimiento sexual cuanto más tiempo formen parte de una relación* |

(35) If consent for sexual intercourse is established, petting and fondling can be assumed | Si existe consentimiento sexual para relaciones sexuales coitales, se asume que también existe para otras actividades (caricias y tocamientos) |

(36) I have discussed sexual consent issues with a friend | He debatido sobre cuestiones relacionadas con el consentimiento sexual con un amigo/a |

(37) I have heard sexual consent issues being discussed by other students on campus | He escuchado a otras personas debatiendo sobre este tema |

(38) I have discussed sexual consent issues with my current (or most recent) partner at times other than during sexual encounters | He debatido sobre cuestiones de consentimiento sexual con mi pareja actual (o la más reciente) en momentos distintos a los encuentros sexuales |

(39) I have not given much thought to the topic of sexual consent [R] | No he pensado mucho en el tema del consentimiento sexual |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moyano, N., Sánchez-Fuentes, M.d., Parra, S.M. et al. Shall We Establish Sexual Consent or Would You Feel Weird? Sexual Objectification and Rape-Supportive Attitudes as Predictors of How Sex is Negotiated in Men and Women. Sexuality & Culture 27, 1679–1696 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10084-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10084-0