Abstract

Background

The Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM) has provided open-access guidelines for cancer since 2014. However, no independent assessment of their quality has been conducted to date. This study aimed to critically evaluate the quality of SEOM guidelines on cancer treatment.

Methods

Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) and AGREE-REX tool was used to evaluate the qualities of the guidelines.

Results

We assessed 33 guidelines, with 84.8% rated as “high quality”. The highest median standardized scores (96.3) were observed in the domain “clarity of presentation”, whereas “applicability” was distinctively low (31.4), with only one guideline scoring above 60%. SEOM guidelines did not include the views and preferences of the target population, nor did specify updating methods.

Conclusions

Although developed with acceptable methodological rigor, SEOM guidelines could be improved in the future, particularly in terms of clinical applicability and patient perspectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Published cancer research is increasing rapidly [1], and having trustworthy health recommendations accessible is in high demand by guideline users [2]. For decision-makers, clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) have emerged to be a reference to improve the quality of care by bringing together the best available scientific evidence into specific recommendations to improve the quality of care [3]. Their development involves identifying and refining a subject area, forming a multidisciplinary panel of experts, conducting a systematic review of the evidence, formulating recommendations based on the evidence, and grading the strength of the recommendations [4]. All the process should be transparent, evidence-based, and involve stakeholder input [5].

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) [6], the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [7] and the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM) [8] guidelines are prepared and reviewed by leading experts and they provide a set of evidence-based recommendations to serve as a guide for healthcare professionals and outline appropriate methods of treatment and care. Particularly, SEOM is a national, non-profit scientific society that promotes studies, training, and research activities. SEOM wants to increase its role as a reference society, a source of opinion, and rigorous knowledge about cancer for all the agents involved, patients, and society in general [8]. The SEOM’s project to develop guidelines started in 2010 as a perceived need by the Spanish oncologists, that required clinical practice documents tailored to the peculiarities of the Spanish healthcare system. Since 2014, open-access CPGs are available to facilitate clinical practice providing an eminently practical view of the most relevant considerations concerning various cancer-related scenarios [9].

To date, no independent assessment of its quality has been made, despite reports indicating that critical reviews of guidelines worldwide show they are not sufficiently robust [10, 11]. The quality of CPGs can be assessed using various tools, such as AGREE II and AGREE-REX, which evaluate the methodological quality, rigor, and transparency of guideline development. These tools can help to identify areas for improvement in CPGs and ensure that they are evidence-based and relevant to clinical practice. In this context, this study aims to critically assess the quality of CPGs on cancer treatment published by SEOM since 2014.

Methods

Study design

This is a critical review of CPGs. We followed rigorous standards [12] and reported our results according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 checklist [13] (Supplementary file 1). Before starting the review process, we published a research protocol online in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository [14].

Eligibility criteria

We considered a definition for CPGs previously reported by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) [15]. The inclusion criteria (all criteria required) were as follows: (a) CPGs for cancer treatment; (b) supported by SEOM; (c) published in English, or Spanish; and (d) published from 2014 onwards.

Exclusion criteria (any criterion required) were: (a) CPGs on cancer prevention, screening, detection, diagnostic, mapping, staging, imaging, scanning, or follow-up without treatment recommendations; (b) CPGs not containing recommendations for specific cancer (pathology-related guidelines); or (c) unavailable papers, surveys, audits, editorials, letters to the editor, case reports or notes.

Literature search

In February 2022, we identified eligible CPGs through electronic searches on MEDLINE (via PubMed), the SEOM website, and the Clinical and Translational Oncology Journal website, an international journal where SEOM guidelines are published. The search strategy for MEDLINE is presented in Supplementary file 2.

Screening and data extraction

Two reviewers performed an independent title and abstract screening and full text afterwards. A third reviewer solved disagreements. We used Rayyan®, a free web-based software tool for conducting reviews [16]. Two reviewers extracted data independently from included guidelines, in a previously piloted form. We extracted a minimum dataset considering the general characteristics of included CPGs. Also, we extracted data for the development of a recommendation mapping. The lack of agreements was resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached. When we found more than one guideline for a specific cancer (also of different guideline versions), we decided to create a publication thread analyzing the CPGs as a whole with all its references.

Quality assessment

Three independent reviewers assessed the quality of included CPGs using the AGREE II tool [17], developed by the International Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) research team. The tool has become a widely used standard for evaluating the methodological quality and transparency of CPGs internationally [18]. The reviewers rated 23 key items across six domains: (1) scope and purpose; (2) stakeholder involvement; (3) rigor of development; (4) clarity of presentation; (5) applicability; and (6) editorial independence. Each item, including the two global rating items, was rated on a 7-point scale (1—strongly disagree to 7—strongly agree). As a complement to AGREE II, only for the guidelines scored as “high quality”, we used the instrument AGREE-REX, a new tool designed in 2019 to evaluate and optimize the clinical credibility and implementability of CPGs recommendations [19, 20]. AGREE-REX includes three key quality domains: clinical applicability (domain 1), values and preferences (domain 2), and implementability (domain 3), comprising 9 items that must be considered to ensure that guidelines recommendations are of high quality. This tool was used by the same three independent authors on a 7-point scale (1—strongly disagree to 7—strongly agree). Furthermore, the evaluator was asked about the recommendation of this guideline in the appropriate context or in the reviewers’ context. All the assessments were performed independently and blinded using an internally piloted data extraction spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel 2019.

Statistical analysis

As suggested by the AGREE II instructions, we calculated domain scores as a sum of the average scores of individual items from all evaluators’ assessments in the domains. Then, we expressed the total scores for each domain as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain. Therefore, the range of possible scores was 0–100%, representing the worst and best possible ratings for each domain, respectively. Each domain assessed with a score of ≥ 60% was considered effectively addressed. We considered CPGs as “high quality” if they scored ≥ 60% in at least three of six AGREE II domains, including domain 3. If three domains or more were assessed with a score of ≥ 60%, except domain 3, they were considered to be of “moderate quality” overall quality. Finally, CPGs scored < 60% in two or more domains and scored < 50% in domain 3 were considered “low quality”.

We performed all statistical analyses in RStudio [21], including boxplot and ggplot2 packages. Descriptive analyses were performed by estimators’ central tendency and dispersion including mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile ranges (IQR). We calculated inter-rater reliability using the average intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (two-way random mixed model), including the 95% confidence interval. ICC can be interpreted as follows, 0–0.2 (poor agreement); 0.3–0.5 (fair agreement); 0.5–0.75 (moderate agreement); 0.75–0.9 (strong agreement); and > 0.9 (almost perfect agreement).

Results

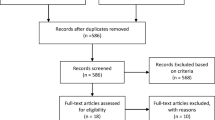

The PRISMA statement flow diagram (Fig. 1) depicts the flow of information through the different phases of our critical review. Finally, 208 relevant references remained for the full-text review, and 69 met the inclusion criteria for detailed analysis (excluded studies are presented in Supplementary file 3). After considering the subsequent updates of the same CPGs, a total of 33 CPGs were included [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

PRISMA 2020 flowchart. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the reviewed CPGs. We identified 25 cancer types. Colorectal and breast cancer were the locations with more publications. On average, SEOM published seven guidelines per year. The year that witnessed the highest production was 2015 (13 guidelines), while 2017 had the lowest production (no guidelines published). Among the identified guidelines, 28 had been published over three years ago.

Table 2 summarizes the standardized domain scores of the AGREE II and the overall quality rating of the CPGs. As per the pre-defined criteria of this study, 84.8% of CPGs (28) were considered “high quality” [23,24,25,26,27,28, 30,31,32,33, 39, 45, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66], 12.0% of CPGs (4) were assessed as “moderate quality” [22, 38, 44, 52, 67,68,69,70] and 3.0% CPGs (1) were considered as “low quality” [29]. A moderate agreement was present across all appraisers in this study (average measures ICC = 0.6; 95% CI 0.4, 0.7). Among the six domains of AGREE II in all guidelines, four median scores were rated ≥ 60 (domains 1, 3, 4, and 6). The highest median standardized scores (96.3) were observed in domain 4 (clarity of presentation), whereas domain 5 (applicability) was distinctively low (31.4), with only one of the CPGs scoring above 60%. Regarding domain 3 (rigor of development), the standardized scores ranged from 55.6 to 86.1 (median = 74.3), and 28 of the CPGs scored above 60.0%. The CPG for gastrointestinal sarcomas (GIST) [48] obtained the highest scores, fulfilling 100% of the criteria in two domains, and > 85.0% in domain 3.

Figure 2 summarizes the item scores of AGREE II. SEOM´s guidelines did not include in their development the views and preferences of the target population as can be inferred from item 5 (1–2, lowest scores). Moreover, they did not clarify the updating methods either, so all obtained the worst score on the Likert scale in item 14 [45]. Also, items 18–21 regarding applicability scored in most cases lower than 4. Specifically, item 21, which refers to monitoring and audit criteria, has a median score of 1.7, being the guideline about glioblastoma the only one with a high score (6.3) in this item [45].

AGREE II item scores of included clinical practice guidelines by the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM) (n = 33). I1—The overall objective(s) of the guideline is (are) specifically described; I2—The health question(s) covered by the guideline is (are) specifi- cally described; I3—The population (patients, public, etc.) to whom the guideline is meant to apply is specifically described; I4—The guide- line development group includes individuals from all the relevant professional groups; I5—The views and preferences of the target population (patients, public, etc.) have been sought; I6—The target users of the guideline are clearly defined; I7—Systematic methods were used to search for evidence; I8—The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described; I9—The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described; I10—The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described; I11—The health benefits, side effects, and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations; I12—There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence; I13—The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication; I14—A procedure for updating the guideline is provided; I15—The recommendations are specific and unambiguous; I16—The different options for management of the condition or health issue are clearly presented; I17—Key recommendations are easily identifiable; I18—The guideline provides advice and/or tools on how the recommendations can be put into practice; I19—The guideline describes facilitators and barriers to its application; I20—The potential resource impli- cations of applying the recommendations have been considered; I21—The guideline presents monitoring and/ or auditing criteria; I22—The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline; I23—Competing interests of guideline development group members have been recorded and addressed

Table 3 summarizes the standardized domain scores of AGREE-REX. Considering only the 28 high-quality CPGs the mean overall AGREE-REX score was 48.5 (SD 11.0) with variability in performance across the individual 9 items. The overall average score of the recommendations was 4.2 out of 7 (SD 0.6). The domain 1 “clinical applicability” got the highest scores (mean 75.8, SD 14.3) and the domain 2 “values and preferences” got the lowest (mean 26.0, SD 12.2). AGREE-REX items that scored the highest were “2. Applicability to Target Users” (mean 6.2; SD 0.7), and “1. Evidence” (mean 5.8; SD 0.5), while the lowest scores were observed for the item “5. Values and Preferences of Patients/Population” (mean 1.6; SD 1.1), and item “6. Values and Preferences of Policy/Decision-Makers” (mean 1.6; SD 1.4).

Discussion

Overall, this critical review provides a thorough analysis of the quality of CPGs published by the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology on cancer treatment along the last nine years. The study also identified the characteristics of the guidelines, including the types of cancer covered and the timeline of their publication. Ultimately, 33 guidelines were included and assessed, with 28 (85.0%) of those being considered “high quality” according to pre-defined criteria; however, their applicability was found to be poor. One of the main strengths of the guidelines is the domain “clarity of presentation”, in which it achieved the highest possible scores, whereas domain “applicability” was distinctively low (31.4), with only one of the CPGs scoring above 60.0%. SEOM’s guidelines did not include in their formulation the views and preferences of the target population. Moreover, they did not specify the updating methods either.

Our results are pointing out that the SEOM is producing CPGs that meet established standards for methodological rigor. Being high scored in “clarity of presentation” is encouraging because it suggests that the SEOM is effectively communicating its recommendations to clinicians and patients. This result is particularly noteworthy given that clear and understandable guidelines are essential for their effective implementation in clinical practice, ensuring that the recommendations are specific and unambiguous, the different options for management of the condition or health issues are clearly presented, and key recommendations are easily identifiable [73].

However, it is concerning that guidelines scored low in “applicability” because it suggests that may not be as useful for clinicians and patients as they could be. Previous research indicates that for clinical guidelines to have an actual impact on processes and ultimately outcomes of care, they need to be not only well developed and based on scientific evidence but also disseminated and implemented in ways that ensure they are actually used by clinicians [71, 72]. Implementation science frameworks have been used to address challenges in implementing clinical practice guidelines [72]. Also, SEOM's guidelines did not include the views and preferences of the target population or specify the updating methods indicates that there is room for improvement in the guidelines development process. Incorporating patient perspectives into guidelines development can improve the relevance and applicability of guidelines to clinical practice [73]. Specifying updating methods is also important to ensure that guidelines remain up-to-date and reflect the latest evidence [5].

Our critical review used both AGREE II and AGREE-REX, tools used to evaluate practice guidelines, but with different focuses. AGREE II is designed to assess the methodological quality and transparency of practice guidelines, while AGREE-REX is designed to evaluate the clinical credibility and implementability of practice guidelines [17, 20]. AGREE-REX is a complement to AGREE II, rather than an alternative, and provides a blueprint for practice guideline development and reporting. Although scoring high in AGREE II is essential, it does not guarantee that recommendations are optimal for targeted users nor the optimal implementation of the recommendations [19]. In our review, we found that recommendations from guidelines scored as “high quality” on AGREE II, did not align with the values and preferences of their target users, whether they be patients or policy makers, according to AGREE-REX. This result has been previously reported elsewhere [20]. In this context, we consider that guidelines that are developed without considering the values and preferences may not be relevant or applicable to their needs, which can lead to poor adherence and outcomes.

Finally, there have been several critical appraisals of the quality of guidelines in cancer [20, 74,75,76], but there are no search results that indicate whether ASCO or ESMO have conducted critical appraisals of the quality of guidelines in cancer. One study used the AGREE tool to assess the quality of oncology guidelines developed in different countries [77]. Another study used the AGREE II tool to assess the methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines with physical activity recommendations for people diagnosed with cancer [76]. The results of these studies showed a heterogeneous quality of existing guidelines in cancer, indicating a need for improvement in the development and reporting of guidelines.

Strengths and limitations

Our research has multiple strengths. We implemented a thorough search strategy to locate SEOM guidelines, and utilized a standardized and globally recognized guidelines appraisal tool (AGREE II). While our study is not the first to critically appraise guidelines [11, 20], it is noteworthy that we are one of the few studies to use the AGREE-REX tool (developed in 2019) for assessing cancer guidelines. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first independent evaluations of the quality of cancer treatment guidelines from a scientific society, which adds to the significance of our findings.

Nevertheless, there are also some limitations to our study that need to be acknowledged. First, our study only assessed the methodological quality of the SEOM guidelines and did not evaluate their impact on clinical practice or patient outcomes. Second, while AGREE II and AGREE-REX are recognized appraisal tools, they do have limitations, and therefore, their application alone may not fully encompass all aspects of guidelines quality. Third, we should not be assumed that having a rigorous methodology means that all issues have been dealt with exhaustively and accurately. Some recommendations could not be sufficiently detailed to guide treatment decisions in specific situations, such as advanced cancer, end of life, elderly, and comorbidities. Fourth, we cannot assume that clinicians’ adherence to these guidelines is high, so having high-quality guidelines does not necessarily mean that clinicians are making the right decisions, as many studies previously reported [78,79,80]. Finally, due to the nature of the study design, our results are limited to the time period of guidelines publication and do not account for any subsequent updates or changes to the guidelines.

It is worth considering the potential redundancy with other cancer treatment guidelines developed by international organizations or societies. While our study focuses on the SEOM guidelines, it is important to acknowledge that other guidelines exist that may provide valuable insights and recommendations. It is worth reflecting on the extent to which these guidelines, taken individually, contribute different nuances and perspectives on cancer treatment and management. In light of this, it is worth asking whether a policy of adapting guidelines [81] might be a more efficient approach than the development of new guidelines from scratch. Such an approach could help to reconcile the differences between guidelines and promote the uptake of best practices across multiple contexts.

Implications for practice and research

Overall, this review emphasizes the importance of producing high-quality and applicable CPGs in oncology to guide clinical practice and improve patient outcomes. The findings provide insights into the strengths and limitations of SEOM's guidelines and highlight areas where improvement can be made to enhance their relevance and usefulness.

Conclusions

SEOM guidelines on cancer treatment have been developed with acceptable methodological rigor although they have some drawbacks that could be improved in the future, such as clinical applicability and items regarding patient views and preferences as well as unmeeting policies.

Data availability statement

The data used in this study is available upon request. Interested researchers can contact the corresponding author for access to the data.

References

Qadir XV, Clyne M, Lam TK, Khoury MJ, Schully SD. Trends in published meta-analyses in cancer research, 2008–2013. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28:5–12.

Elwyn G, Quinlan C, Mulley A, Agoritsas T, Vandvik PO, Guyatt G. Trustworthy guidelines—excellent; customized care tools—even better. BMC Med. 2015;13:199.

Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Westert GP. Effects of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on quality of care: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:385–92.

Woolf S, Schünemann HJ, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Shekelle P. Developing clinical practice guidelines: types of evidence and outcomes; values and economics, synthesis, grading, and presentation and deriving recommendations. Implement Sci. 2012;7:1–12.

Institute of Medicine, Board on Health Care Services, Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. National Academies Press; 2011.

Pentheroudakis G, Curigliano G, Zielinski C. ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines: adapting and adopting new approaches for development, implementation and audit. ESMO Open. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100344.

Shah MA, Oliver TK, Peterson DE, Einhaus K, Schneider BJ, Denduluri N, et al. ASCO clinical practice guideline endorsements and adaptations. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:834–40.

González-del-Alba A, Rodríguez-Lescure Á. 2019 SEOM guidelines (the end of a decade). Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22:169–70.

Rodriguez CA, Martín M. SEOM guidelines 2015: a new era in the collaboration with the Spanish Cancer Research Cooperative Groups. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:937–8.

Barry HC, Cosgrove L, Slawson DC. Where clinical practice guidelines go wrong. Am Fam Phys. 2022;105:350–2.

Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Sola I, Gich I, Delgado-Noguera M, Rigau D, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. BMJ Qual Saf. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2010.042077.

Johnston A, Kelly SE, Hsieh S-C, Skidmore B, Wells GA. Systematic reviews of clinical practice guidelines: a methodological guide. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;108:64–76.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18: e1003583.

Santero M, de Mas J, Rexach I, Marín IC, Rifa B, Bonfill X, et al. Quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines from the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM). 2022. Open Sci Framework. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/6BZFN.

Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E. Committee on standards for developing trustworthy clinical practice guidelines; institute of medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. 2011.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Can Med Assoc J. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090449.

Makarski J, Brouwers MC. The AGREE Enterprise: a decade of advancing clinical practice guidelines. Implement Sci. 2014;9:103.

Brouwers MC, Spithoff K, Kerkvliet K, Alonso-Coello P, Burgers J, Cluzeau F, et al. Development and validation of a tool to assess the quality of clinical practice guideline recommendations. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3: e205535.

Florez ID, Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, Alonso-Coello P, Burgers J, et al. Assessment of the quality of recommendations from 161 clinical practice guidelines using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation-Recommendations Excellence (AGREE-REX) instrument shows there is room for improvement. Implement Sci. 2020;15:1–8.

RStudio Team (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA. http://www.rstudio.com/. Accessed 31 May 2023

Aparicio J, Terrasa J, Durán I, Germà-Lluch JR, Gironés R, González-Billalabeitia E, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the management of germ cell testicular cancer (2016). Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18(12):1187–96.

Ayala de la Peña F, Andrés R, Garcia-Sáenz JA, Manso L, Margelí M, Dalmau E, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines in early stage breast cancer (2018). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(1):18–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-018-1973-6. Epub 2018 Nov 15. PMID: 30443868; PMCID: PMC6339657.

Balañá C, Alonso M, Hernandez A, Perez-Segura P, Pineda E, Ramos A, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for anaplastic gliomas (2017). Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:16–21.

Barretina-Ginesta MP, Quindós M, Alarcón JD, Esteban C, Gaba L, Gómez C, et al. SEOM-GEICO clinical guidelines on endometrial cancer (2021). Clin Transl Oncol. 2022;24:625–34.

Capdevila J, Gómez MA, Guillot M, Páez D, Pericay C, Safont MJ, et al. SEOM-GEMCAD-TTD clinical guidelines for localized rectal cancer (2021). Clin Transl Oncol. 2022;1–12.

Chacón López-Muñiz JI, de la Cruz Merino L, Gavilá Gregori J, Martínez Dueñas E, Oliveira M, Seguí Palmer MA, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines in advanced and recurrent breast cancer (2018). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21:31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-018-02010-w. Epub 2019 Jan 8. PMID: 30617924; PMCID: PMC6339670.

de Juan FA, Álvarez Álvarez R, Casado Herráez A, Cruz Jurado J, Estival González A, Martín-Broto J, et al. SEOM clinical guideline of management of soft-tissue sarcoma (2020). Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(5):922–30.

de Juan A, Redondo A, Rubio MJ, García Y, Cueva J, Gaba L, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for cervical cancer (2019). Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(2):270–8.

Dómine M, Moran T, Isla D, Martí JL, Sullivan I, Provencio M, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) (2019). Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(2):245–55.

Reig M, Forner A, Ávila MA, Ayuso C, Mínguez B, Varela M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Update of the consensus document of the AEEH, AEC, SEOM, SERAM, SERVEI, and SETH. Med Clín (English Edition). 2021;156(9):463-e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcle.2020.09.004.

Gallardo E, Medina J, Sánchez JC, Viúdez A, Grande E, Porras I, et al. SEOM clinical guideline thyroid cancer (2019). Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(2):223–35.

Gómez-España MA, Gallego J, González-Flores E, Maurel J, Páez D, Sastre J, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (2018). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(1):46–54.

Gómez-España MA, Montes AF, Garcia-Carbonero R, Mercadé TM, Maurel J, Martín AM, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for pancreatic and biliary tract cancer (2020). Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(5):988–1000.

González Del Alba A, De Velasco G, Lainez N, Maroto P, Morales-Barrera R, Muñoz-Langa J, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic urothelial bladder cancer (2018). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(1):64–74.

González Del Alba A, Méndez-Vidal MJ, Vazquez S, Castro E, Climent MA, Gallardo E, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer (2020). Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(5):969–79.

González-Flores E, Serrano R, Sevilla I, Viúdez A, Barriuso J, Benavent M, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroenteropancreatic and bronchial neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) (2018). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(1):55–63.

González-Santiago S, Ramón Y, Cajal T, Aguirre E, Alés-Martínez JE, Andrés R, Balmaña J, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (2019). Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22:193–200.

Guillén-Ponce C, Lastra E, Lorenzo-Lorenzo I, Martín Gómez T, Morales Chamorro R, Sánchez-Heras AB, et al. SEOM clinical guideline on hereditary colorectal cancer (2019). Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(2):201–12.

Lázaro M, Valderrama BP, Suárez C, de Velasco G, Beato C, Chirivella I, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for treatment of kidney cancer (2019). Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22:256–69.

Luque R, Benavides M, Del Barco S, Egaña L, García-Gómez J, Martínez-García M, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for management of adult medulloblastoma (2020). Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(5):940–7.

Majem M, Juan O, Insa A, Reguart N, Trigo JM, Carcereny E, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (2018). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(1):3–17.

Majem M, Manzano JL, Marquez-Rodas I, Mujika K, Muñoz-Couselo E, Pérez-Ruiz E, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for the management of cutaneous melanoma (2020). Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(5):948–960.

Martín-Richard M, Carmona-Bayonas A, Custodio AB, Gallego J, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Reina JJ, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer (GC) and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (GEJA) (2019). Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(2):236–44.

Martínez-Garcia M, Álvarez-Linera J, Carrato C, Ley L, Luque R, Maldonado X, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of glioblastoma (2017). Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(1):22–8.

Mesia R, Iglesias L, Lambea J, Martínez-Trufero J, Soria A, Taberna M, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of head and neck cancer (2020). Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(5):913–21.

Nadal E, Bosch-Barrera J, Cedrés S, Coves J, García-Campelo R, Guirado M, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma (2020). Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(5):980–7.

Poveda A, Martinez V, Serrano C, Sevilla I, Lecumberri MJ, de Beveridge RD, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for gastrointestinal sarcomas (GIST) (2016). Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18(12):1221–8.

Provencio Pulla M, Alfaro Lizaso J, de la Cruz Merino L, Gumá I, Padró J, Quero Blanco C, Gómez Codina J, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(12):1014–9.

Redondo A, Guerra E, Manso L, Martin-Lorente C, Martinez-Garcia J, Perez-Fidalgo JA, et al. SEOM clinical guideline in ovarian cancer (2020). Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(5):961–8.

Remon J, Bernabé R, Diz P, Felip E, González-Larriba JL, Lázaro M, et al. SEOM-GECP-GETTHI clinical guidelines for the treatment of patients with thymic epithelial tumours (2021). Clin Transl Oncol. 2022;1–11.

Rueda Domínguez A, Alfaro Lizaso J, de la Cruz Merino L, Gumá I, Padró J, Quero Blanco C, Gómez Codina J, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(12):1005–13.

Rueda Domínguez A, Cirauqui B, García Castaño A, Alvarez Cabellos R, Carral Maseda A, Castelo Fernández B, et al. SEOM-TTCC clinical guideline in nasopharynx cancer (2021). Clin Transl Oncol. 2022;1–11.

Sepúlveda-Sánchez JM, Muñoz Langa J, Arráez MÁ, Fuster J, Hernández Laín A, Reynés G, et al. SEOM clinical guideline of diagnosis and management of low-grade glioma (2017). Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(1):3–15.

Garcia-Saenz JA, Bermejo B, Estevez LG, Palomo AG, Gonzalez-Farre X, Margeli M, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines in early-stage breast cancer 2015. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(12):939–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-015-1427-3. Epub 2015 Oct 26. PMID: 26497356; PMCID: PMC4689767.

Balañá C, Alonso M, Hernandez-Lain A, Perez-Segura P, Pineda E, Ramos A, et al. Correction to: SEOM clinical guidelines for anaplastic gliomas (2017). Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:937.

Santaballa A, Matías-Guiu X, Redondo A, Carballo N, Gil M, Gómez C, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for endometrial cancer (2017). Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(1):29–37.

Santaballa A, Matías-Guiu X, Redondo A, Carballo N, Gil M, Gómez C, et al. Correction to: SEOM clinical guidelines for endometrial cancer (2017). Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:559–60.

González-Flores E, Losa F, Pericay C, Polo E, Roselló S, Safont MJ, et al. SEOM clinical guideline of localized rectal cancer (2016). Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18(12):1163–71.

Gavilá J, Lopez-Tarruella S, Saura C, Muñoz M, Oliveira M, la Cruz-Merino M, Martin, M. SEOM clinical guidelines in metastatic breast cancer 2015. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(12):946–55.

López-Pousa A, Martin Broto J, Martinez Trufero J, Sevilla I, Valverde C, Alvarez R, et al. SEOM clinical guideline of management of soft-tissue sarcoma (2016). Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18(12):1213–20.

Forner A, Reig M, Varela M, Burrel M, Feliu J, Briceño J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Update consensus document from the AEEH, SEOM, SERAM, SERVEI and SETH. Medicina. 2016;146(11):5111–51122.

Sastre J, Díaz-Beveridge R, García-Foncillas J, Guardeño R, López C, Pazo R, et al. Clinical guideline SEOM: hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(12):988–95.

Trigo JM, Capdevila J, Grande E, Grau J, Lianes P. Thyroid cancer: SEOM clinical guidelines. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16(12):1035–42.

Guillén-Ponce C, Serrano R, Sánchez-Heras AB, Teulé A, Chirivella I, Martín T, et al. Clinical guideline seom: hereditary colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(12):962–71.

Aranda E, Aparicio J, Alonso V, Garcia-Albeniz X, Garcia-Alfonso P, Salazar R, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer 2015. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(12):972–81.

Martin-Richard M, Díaz Beveridge R, Arrazubi V, Alsina M, Galan Guzmán M, Custodio AB, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal cancer (2016). Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18(12):1179–86.

Martin-Richard M, Custodio A, García-Girón C, Grávalos C, Gomez C, Jimenez-Fonseca P, et al. Erratum to: SEOM guidelines for the treatment of gastric cancer 2015. Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18:426.

Martin-Richard M, Custodio A, García-Girón C, Grávalos C, Gomez C, Jimenez-Fonseca P, et al. Seom guidelines for the treatment of gastric cancer 2015. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:996–1004.

Llort G, Chirivella I, Morales R, Serrano R, Sanchez AB, Teulé A, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines in Hereditary Breast and ovarian cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17(12):956–61.

Panteli D, Legido-Quigley H, Reichebner C, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines as a quality strategy. In: Busse R, Klazinga N, Panteli D, et al., editors. Improving healthcare quality in Europe: Characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies [Internet]. Copenhagen (Denmark): European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2019. (Health Policy Series, No. 53.) 9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549283/. Accessed 31 May 2023

Sarkies MN, Jones LK, Gidding SS, Watts GF. Improving clinical practice guidelines with implementation science. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;19:3–4.

Selva A, Sanabria AJ, Pequeño S, Zhang Y, Solà I, Pardo-Hernandez H, et al. Incorporating patients’ views in guideline development: a systematic review of guidance documents. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;88:102–12.

Santero M, Meade AG, Acosta-Dighero R, González L, Melendi S, Solà I, et al. European clinical practice guidelines on the use of chemotherapy for advanced oesophageal and gastric cancers: a critical review using the AGREE II and the AGREE-REX instruments. Clin Transl Oncol. 2022;24:1588–604.

Steeb T, Wessely A, Drexler K, Salzmann M, Toussaint F, Heinzerling L, et al. The quality of practice guidelines for melanoma: a methodologic appraisal with the AGREE II and AGREE-REX instruments. Cancers. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12061613.

Shallwani SM, King J, Thomas R, Thevenot O, De Angelis G, Aburub AS, et al. Methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines with physical activity recommendations for people diagnosed with cancer: a systematic critical appraisal using the AGREE II tool. PLoS One. 2019;14: e0214846.

Burgers JS, Fervers B, Haugh M, Brouwers M, Browman G, Philip T, et al. International assessment of the quality of clinical practice guidelines in oncology using the appraisal of guidelines and research and evaluation instrument. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2000–7.

Ferron G, Martinez A, Gladieff L, Mery E, David I, Delannes M, et al. Adherence to guidelines in gynecologic cancer surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:1675–8.

Wolters R, Wöckel A, Janni W, Novopashenny I, Ebner F, Kreienberg R, et al. Comparing the outcome between multicentric and multifocal breast cancer: what is the impact on survival, and is there a role for guideline-adherent adjuvant therapy? A retrospective multicenter cohort study of 8,935 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142:579–90.

Subramanian S, Klosterman M, Amonkar MM, Hunt TL. Adherence with colorectal cancer screening guidelines: a review. Prev Med. 2004;38:536–50.

Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R, Brouwers M, Browman GP, Graham ID, et al. Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:228–36.

Oaknin A, Rubio MJ, Redondo A, De Juan A, Cueva Bañuelos JF, Gil-Martin M, et al. SEOM guidelines for cervical cancer. Clin Trans Oncol. 2015;17(12):1036–1042.

Sepúlveda-Sánchez JM, Langa JM, Arráez MÁ, Fuster J, Laín AH, Reynés, G, et al. Correction to: SEOM clinical guideline of diagnosis and management of low-grade glioma (2017). Clin Trans Oncol. 2018;20(1):108.

Iglesias Docampo LC, Arrazubi Arrula V, Baste Rotllan N, Carral Maseda A, Cirauqui Cirauqui B, Escobar Y, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of head and neck cancer (2017). Clin Trans Oncol. 2018;20(1):75-83.

Mesia R, Iglesias L, Lambea J, Martínez-Trufero J, Soria A, Taberna M, et al. Correction to: SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of head and neck cancer (2020). Clin Trans Oncol. 2021;23(5):1001.

Gallardo E, Méndez-Vidal MJ, Perez-Gracia JL, Sepúlveda-Sánchez JM, Campayo M, Chirivella-González I, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for treatment of kidney cancer (2017). Clin Trans Oncol. 2018;20(1):47–56.

Bellmunt J, Puente J, Garcia de Muro J, Lainez N, Rodríguez C, Duran I, Spanish Society for Medical Oncology (2014). SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Clinical & translational oncology: official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico, 2014;16(12):1043–1050.

Gallardo E, Méndez-Vidal MJ, Pérez-Gracia JL, Sepúlveda-Sánchez JM, Campayo M, Chirivella-González I, García-Del-Muro X, González-Del-Alba A, Grande E, Suárez C. Correction to: SEOM clinical guideline for treatment of kidney cancer (2017). Clinical & translational oncology: official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico, 2019;21(5):692–693.

García-Campelo R, Bernabé R, Cobo M, Corral J, Coves J, Dómine M, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) 2015. Clin Trans Oncol 2015;17(12):1020–1029.

Berrocal A, Arance A, Castellon VE, de la Cruz L, Espinosa E, Cao MG, Larriba J, Márquez-Rodas I, Soria A, Algarra SM. SEOM clinical guideline for the management of malignant melanoma (2017). Clinical & translational oncology: official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico, 2018;20(1):69–74.

Berrocal A, Arance A, Espinosa E, Castaño AG, Cao MG, Larriba JL, Martín JA, Márquez I, Soria A, Algarra SM. SEOM guidelines for the management of Malignant Melanoma 2015. Clinical & translational oncology: official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico, 2015;17(12):1030–1035.

Pastor M, Lopez Pousa A, Del Barco E, Perez Segura P, Astorga BG, Castelo B, et al. (2018). SEOM clinical guideline in nasopharynx cancer (2017). Clin Trans Oncol 2018;20(1):84–88.

Garcia-Carbonero R, JImenez-Fonseca P, Teulé A, Barriuso J, Sevilla I. SEOM clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs) 2014. Clin Trans Oncol. 2014;16(12):1025–1034.

Santaballa A, Barretina P, Casado A, García Y, González-Martín A, Guerra E, et al. SEOM Clinical Guideline in ovarian cancer (2016). ClinTrans Oncol. 2016;18(12):1206–1212.

Gonzalez-Martin A, Bover I, Del Campo JM, Redondo A, Vidal L. SEOM guideline in ovarian cancer 2014. Clin Trans Oncol. 2014;16(12):1067–1071.

Vera R, Dotor E, Feliu J, González E, Laquente B, Macarulla T, et al. SEOM Clinical Guideline for the treatment of pancreatic cancer (2016). Clin Trans Oncol 2016;18(12):1172–1178.

Benavides M, Antón A, Gallego J, Gómez MA, Jiménez-Gordo A, La Casta A, Laquente B, Macarulla T, Rodríguez-Mowbray JR, Maurel J. Biliary tract cancers: SEOM clinical guidelines. Clinical & translational oncology : official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico, 2015;17(12):982–987.

Cassinello J, Arranz JÁ, Piulats JM, Sánchez A, Pérez-Valderrama B, Mellado B, Climent MÁ, Olmos D, Carles J, Lázaro M. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer (2017). Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(1):57–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-017-1783-2. Epub 2017 Nov 13. Erratum in: Clin Transl Oncol. 2018 Jan 5;: PMID: 29134562; PMCID: PMC5785604.

Cassinello J, Arranz JÁ, Piulats JM, Sánchez A, Pérez-Valderrama B, Mellado B, Climent MÁ, Olmos D, Carles J, Lázaro M. Correction to: SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer (2017). Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(1):110–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-017-1823-y. Erratum for: Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(1):57–68. PMID: 29305743; PMCID: PMC6828334.

Cassinello J, Climent MA, González del Alba A, Mellado B, Virizuela JA. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16(12);1060–1066.

Lázaro M, Gallardo E, Doménech M, Pinto A, del Alba AG, Puente J, et al. SEOM Clinical Guideline for treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic urothelial bladder cancer (2016). Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18(12):1197–1205.

Lázaro M, Gallardo E, Doménech M, Pinto Á, González-Del-Alba A, Puente J, et al. Correction to: SEOM Clinical Guideline for treatment of muscleinvasive and metastatic urothelial bladder cancer (2016). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(6):817.

Funding

Open Access Funding provided by Universitat Autònoma Barcelona (UAB). Marilina Santero is funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the contract "FI19/00335” (Co-funded by European Social Fund "Investing in your future").

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to this work and they did not receive any funding for this work.

Ethical approval (Research involving human participants and/or animals) and Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Santero, M., de Mas, J., Rifà, B. et al. Assessing the methodological strengths and limitations of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM) guidelines: a critical appraisal using AGREE II and AGREE-REX tool. Clin Transl Oncol 26, 85–97 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-023-03219-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-023-03219-0