Abstract

Background

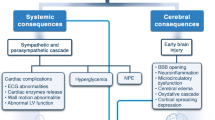

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) occurs frequently after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH). It is a clinical challenge to distinguish between SIRS and incipient infection. Procalcitonin (PCT) has been studied among general critical care patients as a biomarker for infection. We hypothesized that PCT could be useful to distinguish SIRS from sepsis in aSAH patients.

Methods

Prospective, observational study conducted in the multidisciplinary intensive care unit at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL between August 2009 and September 2010. Main predictor was serum PCT obtained on admission and with subsequent episodes of SIRS. A level of 0.2 ng/mL or higher was considered as elevated PCT. Main outcome was clinical infection, which was subsequently subcategorized into major (systemic) and minor (localized) infections in the sensitivity analysis.

Results

Forty consecutive patients were enrolled. Majority (88 %) developed SIRS during the hospitalization. Infection developed in 16 (40 %) patients, with 6 patients meeting criteria for major infection. Overall, PCT was found to be highly specific for all infections and the subcategory of major infections (97 and 93 %, respectively) with related high negative predictive values. Odds ratio for elevated PCT with clinical infections ranged from 25.2 (95 % CI 2.7–233) to 33.3 (95 % CI 4.3–261) for all and major infections, respectively. Related receiver operating characteristic curves for elevated PCT were 0.74 and 0.96 for all and major infections, respectively.

Conclusions

Procalcitonin of 0.2 ng/mL or greater was demonstrated to be very specific for sepsis among patients with aSAH. Further studies should validate this result and establish its clinical applicability.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Feigin VL, Rinkel GJ, Lawes CM, et al. Risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage: an updated systematic review of epidemiological studies. Stroke. 2005;36:2773–80.

van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 2007;369:306–18.

Caplan JM, Colby GP, Coon AL, Huang J, Tamargo RJ. Managing subarachnoid hemorrhage in the neurocritical care unit. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2013;24:321–37.

Oconnor E, Venkatesh B, Mashongonyika C, Lipman J, Hall J, Thomas P. Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as markers of sepsis and outcome in patients with neurotrauma and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004;32:465–70.

Yoshimoto Y, Tanaka Y, Hoya K. Acute systemic inflammatory response syndrome in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:1989–93.

Wartenberg KE, Mayer SA. Medical complications after subarachnoid hemorrhage: new strategies for prevention and management. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:78–84.

Nakamura A, Wada H, Ikejiri M, et al. Efficacy of procalcitonin in the early diagnosis of bacterial infections in a critical care unit. Shock. 2009;31:586–91.

Harbarth S, Holeckova K, Froidevaux C, et al. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:396–402.

Muller B, Becker KL, Schachinger H, et al. Calcitonin precursors are reliable markers of sepsis in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:977–83.

Novotny A, Emmanuel K, Matevossian E, et al. Use of procalcitonin for early prediction of lethal outcome of postoperative sepsis. Am J Surg. 2007;194:35–9.

Suzuki N, Mizuno H, Nezu M, et al. Procalcitonin might help in discrimination between meningeal neuro-Behcet disease and bacterial meningitis. Neurology. 2009;72:762–3.

Martinez R, Gaul C, Buchfelder M, Erbguth F, Tschaikowsky K. Serum procalcitonin monitoring for differential diagnosis of ventriculitis in adult intensive care patients. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:208–10.

Connolly ES Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/american Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43:1711–37.

Muroi C, Hugelshofer M, Seule M, et al. Correlation among systemic inflammatory parameter, occurrence of delayed neurological deficits, and outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:367–75 (discussion 75).

Muroi C, Lemb JB, Hugelshofer M, Seule M, Bellut D, Keller E. Early systemic procalcitonin levels in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2013. doi:10.1007/s12028-013-9844-z.

Muckart DJ, Bhagwanjee S. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference definitions of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and allied disorders in relation to critically injured patients. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1789–95.

Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. [Erratum appears in Am J Infect Control. 2008; 36(9):655]. Am J Infect Control 2008; 36:309–32.

Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1589–96.

O’Grady NP, Barie PS, Bartlett JG, et al. Guidelines for evaluation of new fever in critically ill adult patients: 2008 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1330–49.

Hug A, Murle B, Dalpke A, Zorn M, Liesz A, Veltkamp R. Usefulness of serum procalcitonin levels for the early diagnosis of stroke-associated respiratory tract infections. Neurocrit Care. 2011;14:416–22.

Assicot M, Gendrel D, Carsin H, Raymond J, Guilbaud J, Bohuon C. High serum procalcitonin concentrations in patients with sepsis and infection. Lancet. 1993;341:515–8.

Heper Y, Akalin EH, Mistik R, et al. Evaluation of serum C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-10 levels as diagnostic and prognostic parameters in patients with community-acquired sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:481–91.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this research. Clinical Research and Feasibility (CRF) award and Mayo Clinic Foundation supported the costs of procalcitonin laboratory testing and study analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Procalcitonin assay

Procalcitonin is measured in this homogeneous automated immunofluorescent assay on the BRAHMS Kryptor. The Kryptor uses time resolved amplified cryptate emission technology based on a nonradioactive transfer of energy. This transfer occurs between 2 fluorescent tracers: the donor (europium cryptate) and the acceptor (XL665). In the ProCT assay, a sheep polyclonal antibody against calcitonin is labeled with europium cryptate and a mouse monoclonal antibody against catacalcin is labeled with XL665. ProCT is sandwiched between the 2 antibodies, bringing them into close proximity. When the antigen–antibody complex is excited with a nitrogen laser at 337 nm, some fluorescent energy is emitted at 620 nm, and the rest is transferred to XL665. This energy is then emitted as fluorescence at 665 nm. A ratio of the energy emitted at 665 nm to that emitted at 620 nm (internal reference) is calculated for each sample. Signal intensity is proportional to the number of antigen–antibody complexes formed, and therefore to antigen concentration.

Criteria for the infections (from the Ref. [17])

Laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection Patient has recognized pathogen cultured from 1 or more blood cultures and organism cultured from blood is not related to an infection at another site.

Meningitis or ventriculitis Patient has organisms cultured from cerebrospinal fluid.

Pneumonia One or more serial chest radiographs showing new or progressive and persistent infiltrate, consolidation, or cavitation.

UTI Positive urine culture for ≥105 microorganisms per cc of urine with no more than 2 species of organisms and fever (temperature >38 °C).

Sinusitis Positive radiographic examination (CT scan).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Festic, E., Siegel, J., Stritt, M. et al. The Utility of Serum Procalcitonin in Distinguishing Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome from Infection After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 20, 375–381 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-014-9960-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-014-9960-4