Abstract

Background

Therapeutic hypothermia is commonly used in comatose survivors’ post-cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). It is unknown whether outcome predictors perform accurately after hypothermia treatment.

Methods

Post-CPR comatose survivors were prospectively enrolled. Six outcome predictors [pupillary and corneal reflexes, motor response to pain, and somatosensory-evoked potentials (SSEP) >72 h; status myoclonus, and serum neuron-specific enolase (NSE) levels <72 h] were systematically recorded. Poor outcome was defined as death or vegetative state at 3 months. Patients were considered “sedated” if they received any sedative drugs ≤12 h prior the 72 h neurological assessment.

Results

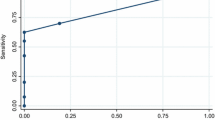

Of 85 prospectively enrolled patients, 53 (62%) underwent hypothermia. Furthermore, 53 of the 85 patients (62%) had a poor outcome. Baseline characteristics did not differ between the hypothermia and normothermia groups. Sedative drugs at 72 h were used in 62 (73%) patients overall, and more frequently in hypothermia than in normothermia patients: 83 versus 60% (P = 0.02). Status myoclonus <72 h, absent cortical responses by SSEPs >72 h, and absent pupillary reflexes >72 h predicted poor outcome with a 100% specificity both in hypothermia and normothermia patients. In contrast, absent corneal reflexes >72 h, motor response extensor or absent >72 h, and peak NSE >33 ng/ml <72 h predicted poor outcome with 100% specificity only in non-sedated patients, irrespective of prior treatment with hypothermia.

Conclusions

Sedative medications are commonly used in proximity of the 72-h neurological examination in comatose CPR survivors and are an important prognostication confounder. Patients treated with hypothermia are more likely to receive sedation than those who are not treated with hypothermia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.References

Booth CM, et al. Is this patient dead, vegetative, or severely neurologically impaired? Assessing outcome for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2004;291(7):870–9.

Zheng ZJ, et al. Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998. Circulation. 2001;104(18):2158–63.

Lloyd-Jones D, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):e46–e215.

Peberdy MA, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58(3):297–308.

Lim C, et al. The neurological and cognitive sequelae of cardiac arrest. Neurology. 2004;63(10):1774–8.

Bates D, et al. A prospective study of nontraumatic coma: methods and results in 310 patients. Ann Neurol. 1977;2(3):211–20.

Bernard SA, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):557–63.

Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549–56.

American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2005;112(24 Suppl):IV1–203.

Sunde K, et al. Determination of prognosis after cardiac arrest may be more difficult after introduction of therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2006;69(1):29–32.

Wijdicks EF, et al. Practice parameter: prediction of outcome in comatose survivors after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;67(2):203–10.

Wijman CA, et al. Prognostic value of brain diffusion-weighted imaging after cardiac arrest. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(4):394–402.

Lowry R. VassarStats: web site for statistical computation [cited 2009 November]. http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html.

Bouwes A, et al. Somatosensory evoked potentials during mild hypothermia after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Neurology. 2009;73(18):1457–61.

Bertz RJ, Granneman GR. Use of in vitro and in vivo data to estimate the likelihood of metabolic pharmacokinetic interactions. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32(3):210–58.

Tortorici MA, Kochanek PM, Poloyac SM. Effects of hypothermia on drug disposition, metabolism, and response: a focus of hypothermia-mediated alterations on the cytochrome P450 enzyme system. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9):2196–204.

Arpino PA, Greer DM. Practical pharmacologic aspects of therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(1):102–11.

Sessler DI. Complications and treatment of mild hypothermia. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(2):531–43.

Fukuoka N, et al. Biphasic concentration change during continuous midazolam administration in brain-injured patients undergoing therapeutic moderate hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2004;60(2):225–30.

Fritz HG, et al. The effect of mild hypothermia on plasma fentanyl concentration and biotransformation in juvenile pigs. Anesth Analg. 2005;100(4):996–1002.

Kress JP, Pohlman AS, Hall JB. Sedation and analgesia in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(8):1024–8.

Chamorro C, et al. Anesthesia and analgesia protocol during therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(5):1328–35.

Zandbergen EG, et al. Prediction of poor outcome within the first 3 days of postanoxic coma. Neurology. 2006;66(1):62–8.

Tiainen M, et al. Serum neuron-specific enolase and S-100B protein in cardiac arrest patients treated with hypothermia. Stroke. 2003;34(12):2881–6.

Oksanen T, et al. Predictive power of serum NSE and OHCA score regarding 6-month neurologic outcome after out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation and therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2009;80(2):165–70.

Rundgren M, et al. Neuron specific enolase and S-100B as predictors of outcome after cardiac arrest and induced hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2009;80(7):784–9.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stephanie Kemp for administrative support for this study and Marion Buckwalter, Chitra Venkatasubramanian, Amie Hsia, Maarten Lansberg, Neil Schwartz, and Gregory Albers for their assistance with patient enrollment. Dr. Wijman has received funding from the following grants for this research: AHA Scientist Development Award, 043275N, and NIH RO1 HL089116-01A2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The statistical analyses were conducted by Drs. Michael Mlynash and Edgar A. Samaniego.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Samaniego, E.A., Mlynash, M., Caulfield, A.F. et al. Sedation Confounds Outcome Prediction in Cardiac Arrest Survivors Treated with Hypothermia. Neurocrit Care 15, 113–119 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-010-9412-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-010-9412-8

Keywords

Profiles

- Edgar A. Samaniego View author profile