Abstract

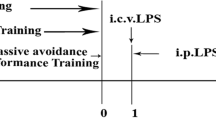

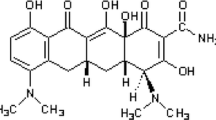

Cognitive dysfunction, sickness-like behavior, for instance, anxiety, and depression are common aspects of neuropsychiatry often associated with neurodegenerative disorders. Growing evidence suggests that high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) may act as a proinflammatory cytokine that aggravates neurobehavioral dysfunction. However, the detailed underlying mechanism is still elusive. Here we focus on determining the relationship between lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation (in both in vitro and in vivo models), cognitive dysfunction, sickness-like behavior and thus decode the impact of HMGB1 inhibition (using Glycyrrhizin; Gcy as an antagonist). Using a mice model of repeated LPS (1 mg/kg, i.p. for 4 days) injections, we found that LPS induced neurobehavioral deficit and a strong proinflammatory response with increased proinflammatory markers, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase) at 7 days after the final dose of LPS compared to control animals. Our findings suggest that neurobehavioral dysfunction strongly correlates with the proinflammatory immune response following LPS stimulation. In vitro Gcy pretreatment to LPS-activated BV2 microglia cells significantly reduced nitrite and reactive oxygen species production, along with diminished expression of classical proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS). These key proinflammatory changes with LPS and Gcy treatment are also found in vivo mice model and correlate with improved cognitive function and reduced anxiety/depression. Together, these results show that blocking HMGB1 using Gcy abrogated the cognitive dysfunction, sickness-like behavior of anxiety and depression induced by LPS which can be a promising avenue for crucial neurobehavioral dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Troubat R, et al. “Neuroinflammation and depression: A review,” Eur J Neurosci. 2020; p. ejn.14720. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.14720.

Weintraub D, Mamikonyan E. The Neuropsychiatry of Parkinson Disease: A Perfect Storm. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(9):998–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2019.03.002.

Dendrou CA, Fugger L, Friese MA. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(9):545–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3871.

Guzman-Martinez L, Maccioni RB, Andrade V, Navarrete LP, Pastor MG, Ramos-Escobar N. “Neuroinflammation as a Common Feature of Neurodegenerative Disorders,” Front Pharmacol. 2019; 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.01008.

Cunningham C, Hennessy E. Co-morbidity and systemic inflammation as drivers of cognitive decline: new experimental models adopting a broader paradigm in dementia research. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-015-0117-2.

Haapakoski R, Mathieu J, Ebmeier KP, Alenius H, Kivimäki M. Cumulative meta-analysis of interleukins 6 and 1β, tumour necrosis factor α and C-reactive protein in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;49:206–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.001.

Park C, et al. Probiotics for the treatment of depressive symptoms: An anti-inflammatory mechanism? Brain Behav Immun. 2018;73:115–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.006.

Farooq RK, Tanti A, Ainouche S, Roger S, Belzung C, Camus V. A P2X7 receptor antagonist reverses behavioural alterations, microglial activation and neuroendocrine dysregulation in an unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) model of depression in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;97:120–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.07.016.

Harland M, Torres S, Liu J, Wang X. Neuronal Mitochondria Modulation of LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation. J Neurosci. 2020;40(8):1756–65. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2324-19.2020.

Batista CRA, Gomes GF, Candelario-Jalil E, Fiebich BL, de Oliveira ACP. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation as a Bridge to Understand Neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2293. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20092293.

Guo L-T, et al. Baicalin ameliorates neuroinflammation-induced depressive-like behavior through inhibition of toll-like receptor 4 expression via the PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16(1):95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-019-1474-8.

Park BS, Lee J-O. Recognition of lipopolysaccharide pattern by TLR4 complexes. Exp Mol Med. 2013;45(12):e66–e66. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2013.97.

Fiebich BL, Batista CRA, Saliba SW, Yousif NM, de Oliveira ACP. “Role of Microglia TLRs in Neurodegeneration,” Front Cell Neurosci 2018; 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2018.00329.

Zhao J, et al. Neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment in mice. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):5790. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42286-8.

Magna M, Pisetsky DS. The Role of HMGB1 in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases. Mol Med. 2014;20(1):138–46. https://doi.org/10.2119/molmed.2013.00164.

Lotze MT, Tracey KJ. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1): nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(4):331–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1594.

Iori V, et al. Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts is upregulated in temporal lobe epilepsy and contributes to experimental seizures. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;58:102–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2013.03.006.

Ravizza T, et al. High Mobility Group Box 1 is a novel pathogenic factor and a mechanistic biomarker for epilepsy. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;72:14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2017.10.008.

Pardo-Peña K, Sánchez-Lira A, Salazar-Sánchez JC, Morales-Villagrán A. A novel online fluorescence method for in-vivo measurement of hydrogen peroxide during oxidative stress produced in a temporal lobe epilepsy model. NeuroReport. 2018;29(8):621–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0000000000001007.

Terrone G, Frigerio F, Balosso S, Ravizza T, Vezzani A. Inflammation and reactive oxygen species in status epilepticus: Biomarkers and implications for therapy. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;101:106275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.04.028.

Li J, Shi J, Sun Y, Zheng F. Glycyrrhizin, a Potential Drug for Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Inhibiting High-Mobility Group Box 1. DNA Cell Biol. 2018;37(12):941–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/dna.2018.4444.

Mollica L, et al. Glycyrrhizin Binds to High-Mobility Group Box 1 Protein and Inhibits Its Cytokine Activities. Chem Biol. 2007;14(4):431–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.007.

Akman T, et al. The Neuroprotective Effect of Glycyrrhizic Acid on an Experimental Model of Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Inflammation. 2015;38(4):1581–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10753-015-0133-1.

Bodea L-G, et al. Neurodegeneration by activation of the microglial complement-phagosome pathway. J Neurosci. 2014;34(25):8546–56. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5002-13.2014.

Xiong X, et al. Glycyrrhizin protects against focal cerebral ischemia via inhibition of T cell activity and HMGB1-mediated mechanisms. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-016-0705-5.

Kumar A, Alvarez-Croda D-M, Stoica BA, Faden AI, Loane DJ. Microglial/Macrophage Polarization Dynamics following Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33(19):1732–50. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2015.4268.

Beier EE, Neal M, Alam G, Edler M, Wu L-J, Richardson JR. Alternative microglial activation is associated with cessation of progressive dopamine neuron loss in mice systemically administered lipopolysaccharide. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;108:115–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2017.08.009.

Kumar A, Barrett JP, Alvarez-Croda D-M, Stoica BA, Faden AI, Loane DJ. NOX2 drives M1-like microglial/macrophage activation and neurodegeneration following experimental traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;58:291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2016.07.158.

Bauer ME, Teixeira AL. Inflammation in psychiatric disorders: what comes first? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019;1437(1):57–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13712.

Wong M-L, et al. Inflammasome signaling affects anxiety- and depressive-like behavior and gut microbiome composition. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(6):797–805. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.46.

Franklin TC, Xu C, Duman RS. Depression and sterile inflammation: Essential role of danger associated molecular patterns. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;72:2–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2017.10.025.

Czura CJ, Yang H, Tracey KJ. High Mobility Group Box–1 as a Therapeutic Target Downstream of Tumor Necrosis Factor. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(s2):S391–6. https://doi.org/10.1086/374753.

Bianchi ME, Crippa MP, Manfredi AA, Mezzapelle R, Rovere Querini P, Venereau E. High-mobility group box 1 protein orchestrates responses to tissue damage via inflammation, innate and adaptive immunity, and tissue repair. Immunol Rev. 2017;280(1):74–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12601.

Gao H-M, Zhou H, Zhang F, Wilson BC, Kam W, Hong J-S. HMGB1 Acts on Microglia Mac1 to Mediate Chronic Neuroinflammation That Drives Progressive Neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2011;31(3):1081–92. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3732-10.2011.

Maroso M, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 and high-mobility group box-1 are involved in ictogenesis and can be targeted to reduce seizures. Nat Med. 2010;16(4):413–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2127.

Mittal D, Saccheri F, Vénéreau E, Pusterla T, Bianchi ME, Rescigno M. TLR4-mediated skin carcinogenesis is dependent on immune and radioresistant cells. EMBO J. 2010;29(13):2242–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2010.94.

Paudel YN, et al. HMGB1: A Common Biomarker and Potential Target for TBI, Neuroinflammation, Epilepsy, and Cognitive Dysfunction. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:628. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00628.

Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418(6894):191–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00858.

Shi Y, Zhang L, Teng J, Miao W. HMGB1 mediates microglia activation via the TLR4/NF-κB pathway in coriaria lactone induced epilepsy. Mol Med Rep. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2018.8485.

Lian Y-J, et al. Ds-HMGB1 and fr-HMGB induce depressive behavior through neuroinflammation in contrast to nonoxid-HMGB1. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;59:322–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2016.09.017.

Cao Z-Y, et al. Glycyrrhizic acid as an adjunctive treatment for depression through anti-inflammation: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Affect Disord. 2020;265:247–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.048.

Funding

This study was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (BT/RLF/13/2014), and SGPGI intramural research grant (A-18-PGI/IMP/80/2019) to AK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.G. designed the research and contributed to conceptualizing. D.G, A.K. helped in experimenting and data analysis. D.G., A.S., A.K., N.S. contributed to drafting the article, edited, revised and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All animal work and experiments are ethically approved and carried out in accordance with the SGPGIMS, institutional guidelines.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript disclose no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghosh, D., Singh, A., Kumar, A. et al. High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) inhibition attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive dysfunction and sickness-like behavior in mice. Immunol Res 70, 633–643 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-022-09295-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-022-09295-8