Abstract

The human gastrointestinal tract houses an enormous microbial ecosystem. Recent studies have shown that the gut microbiota plays significant physiological roles and maintains immune homeostasis in the human body. Dysbiosis, an imbalanced gut microbiome, can be associated with various disease states, as observed in infectious diseases, inflammatory diseases, autoimmune diseases, and cancer. Modulation of the gut microbiome has become a therapeutic target in treating these disorders. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from a healthy donor restores the normal gut microbiota homeostasis in the diseased host. Ample evidence has demonstrated the efficacy of FMT in recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (rCDI). The application of FMT in other human diseases is gaining attention. This review aims to increase our understanding of the mechanisms of FMT and its efficacies in human diseases. We discuss the application, route of administration, limitations, safety, efficacies, and suggested mechanisms of FMT in rCDI, autoimmune diseases, and cancer. Finally, we address the future perspectives of FMT in human medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The human microbiota consists of a diverse multitude of microorganisms that establish in niches throughout the human body and outnumber the host’s cells by tenfold [1]. The majority of the human microbiome is found colonizing the gastrointestinal (GI) tract [2]. The inoculation process begins at birth following exposure of the “essentially germ-free child” to maternal and environmental microorganisms [1, 3, 4]. The infant microbiome is rich in Bifidobacterium longum, which is notable for the digestion of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [1, 4]. SCFAs are not only an energy source for enterocytes, but they also act as ligands in molecular pathways that mediate metabolism and modulate immunity [2, 5].

The human immune system has evolved to be in homeostasis with its microbiome [6]. Although the adult microbiome is thought to remain relatively stable, alterations in composition and quantity can vary with diet, environmental factors, age, and genetics [7, 8]. Alterations in the microbiota population can have a variety of effects on host health, notably by dysregulating metabolic and signaling pathways, decreasing SCFA production, increasing toxic metabolite production, increasing inflammation, and diminishing immune response [2, 5]. Distinct microbe populations have been found to be associated with various disease states, such as infection, autoimmunity, metabolic diseases, and cancer [9,10,11,12,13,14]. On the other hand, certain strains of microorganisms, collectively known as probiotics, confer positive health benefits on the host. Others prevent the growth of harmful bacteria through competitive and noncompetitive mechanisms. Thus, it is hypothesized that remedying dysbiosis, an imbalance between microbiota and host [10], and restoring the diversity and composition of the microbiome can rectify dysregulated metabolisms and immunological responses. In 1958, Eiseman et al. [15] serendipitously pioneered the field of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) with their use of fecal enema to successfully treat patients with pseudomembranous colitis. A subsequent study by Hentges and Freter in 1962 suggested that manipulation of gut microflora can be of therapeutic value in intestinal infection [16]. Restoring the gut microbiome using FMT is now a well-recognized strategy for the management of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (rCDI) in patients who do not respond well to traditional treatment methods. Currently, the US FDA has approved FMT to be used without requiring an investigational new drug (IND) application to treat rCDI in patients who are nonresponsive to standard therapy. However, IND applications are necessary for all other investigational uses of FMT.

FMT is a process by which a sample of a healthy microbiome is transferred to a host with some sort of dysbiosis. The goal is the recolonization of the host gut with beneficial microorganisms and the restoration of eubiosis. It is believed that FMT originated in fourth-century China, whereby fecal material was administered orally to treat patients with diarrhea [10, 17]. FMT was further explored in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries for veterinary treatments before it was rediscovered more recently for human medicine. As discussed above, the first reported use of FMT in western medicine dates back to 1958, when Eiseman and his team documented positive outcomes after fecal enema was administered to patients with diarrhea secondary to antibiotic use [15]. Currently, FMT is performed with either fresh donor stool or frozen prepared samples from healthy volunteers or family members. Following its success in treating rCDI, FMT has been explored to treat other GI and extra-GI diseases (Table 1). Currently, more than 200 clinical trials have been conducted on the applications of FMT in the treatment of various inflammatory and autoimmune disorders as well as cancers. Here, we will discuss the current understanding of the use of FMT in (i) rCDI, (ii) autoimmune disorders, and (iii) cancer. Finally, we will explore the future perspective of FMT in human medicine.

FMT in rCDI

Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile), a spore-forming, gram-positive anaerobic, toxin-producing Bacillus, is widely niched in the intestinal tract of humans and animals and in the environment. rCDI, characterized as a toxin-mediated intestinal disease, is now considered one of the most common causes of healthcare-associated infections and a serious public health challenge. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is one of the major risk factors for rCDI. Antibiotic-mediated gut microbiota dysbiosis has been best characterized in those with C. difficile infection. Therefore, reconstitution of normal microbial homeostasis is deemed a key strategy in the treatment of rCDI patients.

The effectiveness of FMT in rCDI can vary with the route of infusion, the amount of feces administered, the therapy prior to infusion, and the concomitant treatment. The route of FMT administration, safety, and effectiveness in rCDI have been extensively evaluated. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies have demonstrated that FMT is highly effective and considerably safe, with higher clinical resolution rates through lower GI FMT delivery vs. the upper GI route [33,34,35]. There was no significant difference in outcome observed in samples originating from unrelated donors vs. closely related ones; stool banks have been established to meet the growing demands with the added benefit of reducing the cost of treatment. Additionally, donors undergo screening to reduce the risks of spreading infection and are advised to avoid any foods and substances the donor may be allergic to prior to sample collection. Given these considerations, the FDA continues to advise caution regarding potential adverse outcomes (https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/fecal-microbiota-transplantation-safety-alert-risk-serious-adverse-events-likely-due-transmission). A randomized, controlled trial study demonstrated that duodenal infusion of donor fecal samples is significantly more effective than vancomycin alone in treating rCDI [36]. Hvas et al. reported that the combination of FMT and vancomycin was superior to fidaxomicin or vancomycin alone in patients with rCDI [37]. Experimental studies in a murine model of CDI relapse indicated that, although administration of vancomycin can suppress both C. difficile colonization and cytotoxin titers, it cannot eradicate C. difficile completely and leads to rapid relapse, concomitantly with a consistently low diversity of gut microbiota in mice. On the other hand, FMT after vancomycin treatment can clear C. difficile and lead to a diverse, healthy microbiota, indicating FMT provides additional assistance in the restoration of the gut microbiota [38, 39]. Buffie et al. validated that the loss of specific bacterial taxa with the development of infection leads to susceptibility to C. difficile in mice. They reported that Clostridioides cindens was associated with resistance to C. difficile infection, and adoptive transfer of resistance-associated intestinal bacteria after antibiotic exposure reinforces resistance to C. difficile infection [40]. Other studies have also corroborated that FMT is an effective and safe therapy for rCDI [41, 42].

Mechanisms of FMT in rCDI

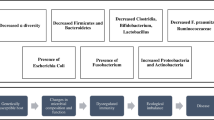

The specific mechanism whereby FMT leads to clinical recovery in rCDI is unclear. To date, the prevailing theories include: (i) direct competition of C. difficile with commensal microbiota administered by FMT [43], (ii) changes in bile acid metabolism [40], (iii) repair of the gut barrier by stimulation of the mucosal immune system [43], and (iv) reconstitution of alpha diversity that contributes to colonization resistance against C. difficile [44, 45] (Fig. 1). Competition among variant gut microbiota, including competitive niche exclusion and nutritional resources, as well as the production of bacteriocins, which possess bactericidal or bacteriostatic activity against competitors, can interfere with the C. difficile population [46]. It has been reported that bile acid metabolism is involved in the pathogenesis of rCDI. Bile acids, generated from cholesterol and synthesized in the liver, are modified in the colon by indigenous gut microbiota and metabolized into secondary bile acids. Bile acids can regulate the composition of the gut microbiota, and different bile acids can either stimulate or inhibit the life cycle of C. difficile. The primary bile salt taurocholate is a common component used in C. difficile growth media, while the secondary bile acid, lithocholic acid, is an inhibitor of C. difficile spore germination [47]. Weingarden et al. reported that pre-FMT fecal samples contain high concentrations of primary bile acids and bile salts, while secondary bile acids are almost undetectable. In contrast, the concentrations of secondary bile acids were comparable between post-FMT stool samples and non-CDI donor samples, which indicated that the metabolism of bile acids was disturbed in patients with rCDI and that FMT can correct rCDI by normalizing the microbiome composition and bile acid metabolism [48].

Hypothetical mechanism of FMT. Possible mechanisms of FMT: (1) increasing microbial diversity that contributes to gut homeostasis; (2) direct competition for niches and nutrition with pathogens; (3) alteration of microbial metabolites such as increasing the production of SCFAs and changing bile acid metabolism; (4) repairing the gut barrier by stimulation of the mucosal immune system and by providing the essential tonic signals to regenerate epithelial cells and produce mucin and antimicrobial peptides; (5) modulation of the immune system through providing essential signals for proper development, education, and epigenetic regulation of immune cells; and (6) acting on gut-brain axis via intrinsic and extrinsic factors, modulating the function of both the enteric and central nervous systems

Gut barrier dynamic entities interacting and responding to various stimuli are an important guard against pathogen invasions. The immune system is one of the important components of the gut barrier. In RegIIIγ (−/−) mice, reduction of RegIIIγ expression, a secreted antibacterial lectin, may lead to increased bacterial colonization of the intestinal epithelial surface and activation of intestinal adaptive immune responses [49]. The immune response in CDI can be either protective or harmful, with respect to the specific C. difficile strains and the attributes of the individual host. For example, the severity and worse outcomes in rCDI are associated with intestinal inflammation featured by higher levels of fecal IL-8 and CXCL5, not fecal pathogen burden [50]. FMT can reshape the gut barrier by providing essential tonic signals to regenerate epithelial cells and produce mucin and antimicrobial peptides [43]. A phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (NCT03183128) on an investigational microbiome therapeutic (SER-109) composed of purified Firmicutes spores for the treatment of recurrent C. difficile infection showed that SER-109 was superior to placebo in reducing the risk of rCDI and with a safety profile similar to that of placebo. Engraftment of the SER-109 microbial species was evident and associated with an increase in secondary bile acids in the SER-109 recipients from week 1 and persisted through the end of the study. Competition for essential nutrients between the spore-forming Firmicutes and C. difficile and modulation of bile acid composition could negatively affect C. difficile sporulation, germination, and colonization in the SER-109 recipients [21].

Seekatz et al. reported a relative increase in the abundance of Bacteroidetes and a decrease in the abundance of Proteobacteria after FMT, with the composition and diversity resembling the donor profile more than the microbiota prior to transplantation, followed by functional changes in promoting colonization resistance [45]. Another study also indicated that the lower alpha diversity in rCDI patients’ pre-FMT samples was restored upon FMT. It was observed that the microbial composition also altered with post-FMT, with similar abundances in Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Bacteroidaceae between responder and donor samples. Based on these results, the regression tree-based model can predict recurrence accurately [51]. Hence, reconstitution of the normal microbial diversity and community structure through FMT is an attractive therapy to prevent pathogen infections in the gut.

FMT in Autoimmune Disorders

Advances in deciphering the roles of gut microbiota in human health and evidence of cross-talk between the microbiome and the human body have inspired a new paradigm in treating autoimmune disorders by manipulation of the gut microbiota via FMT. Here, we will highlight the salient findings in studies of FMT in several autoimmune disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), multiple sclerosis (MS), psoriasis, autoimmune arthritis, and type 1 diabetes (T1D) (Table 2).

FMT in IBD

Since the late 1980s, multiple case reports and cohort studies have demonstrated that FMT delivered via enema or colonic infusion could lead to clinical remission in ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) [61]. FMT applications ranged from single to multiple doses. The pooled results from these studies showed FMT achieved clinical remission in 33% [95% confidence interval (CI) = 23–43%] for UC and 52% [95% CI = 31–72%] for CD. Recently, multiple randomized controlled trials have shown promising results using FMT for mild to moderate UC. Investigations for pouchitis and Crohn’s disease are ongoing [62, 63].

FMT in UC

Five randomized controlled trials using FMT to treat mild to moderate UC have been published from 2015 to 2022 [14, 25, 26, 64, 65] (Table 3). Patients with mild to moderate disease, defined by Mayo scores between 4 and 10, were studied. The primary outcomes were corticosteroid-free clinical remission and endoscopic remission or response. Rossen et al. [26] administered two doses of FMT to UC patients via the nasoduodenal route for 3 weeks but did not achieve a significant response. On the contrary, Moayyedi et al. [25] demonstrated that FMT delivered by enema given once a week for 6 weeks significantly induced clinical remission in 9/38 (24%) of the FMT-treated group vs. 2/37 (5%) placebo using water enema. Each specimen was donated by a healthy individual donor. Surprisingly, this study noted a super donor effect, where FMT from a single donor resulted in a significantly higher number of recipients achieving remission. It is likely that the success of FMT depended on the microbial diversity and composition of the stool donor. High diversity of the gut microbiota, particularly in the donor, appears to best predict a patient’s positive response to FMT. In 2017, Paramsothy et al. [64] illustrated that intensive dosing of FMT from pooled donors via enema given 5 days/week for 8 weeks after one colonoscopy infusion was able to achieve clinical remission in 11 of 41 (27%) patients when compared with 3 of 40 (8%) who were assigned placebo (risk ratio 3.6, 95% CI 1.1–11.9; p = 0.021). The improvement is associated with an increase in distinct microbial diversity, but the response was unrelated to the presence of pathobionts with Fusobacterium spp. Costello et al. [14] conducted a 1-week treatment with anaerobically prepared pooled donor FMT. The significant primary outcomes of steroid-free remission and endoscopic remission were achieved in 12 of the 38 participants (32%) receiving anaerobic FMT compared with 3 of the 35 (9%) receiving autologous FMT (difference, 23% [95% CI, 4–42%]; odds ratio, 5.0 [95% CI, 1.2–20.1]; p = 0.03). In 2022, Haifer et al. [65] published the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) using oral lyophilized capsule FMT in treating mild to moderate UC. Patients were given 2 weeks of amoxicillin, metronidazole, and doxycycline before randomizing to receive oral lyophilized FMT or placebo capsules for 8 weeks. Therapeutic IBD medications were continued, including mesalamine, biologics, and corticosteroids. Steroid therapy was tapered as per protocol. The regimen included six capsules four times a day for 1 week, then six capsules twice daily for 1 week, followed by six capsules daily for the remaining 6 weeks.

The primary outcome (Fig. 2) showed a significant response in 8 of 16 patients (50%) receiving FMT vs. 3 of 19 patients (16%) receiving placebo (OR: 4.63; 95% CI: 1.74–12.30; p = 0.002). Steroid-free clinical remission rates and endoscopic remission rates were 69% vs. 26% (p = 0.012) and 44% vs. 16% (p = 0.074) in the FMT and placebo arms, respectively. Relapse occurred after induction, but all the patients had sustained responses with continued maintenance therapy.

Primary outcomes of the five RCTs of FMT in mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. The bar graphs highlight the efficacies of FMT in the induction of clinical remission for mild to moderate UC in five RCTs. The Rosen study using nasoduodenal delivery of FMT over a 3-week period showed no statistical significance, whereas the other four RCTs demonstrated the effectiveness of FMT for induction of clinical remission when compared to placebo. The pooled data from these RCTs showed that the NNT is 3, which is comparable to other effective medical therapies for IBD

Both the upper and lower routes of administration are effective. The pooled data from these 5 RCTs showed that FMT, when compared to placebo, can achieve clinical and endoscopic remission. The estimated number needed to treat (NNT) is 3. This NNT to achieve remission is similar to using mesalamine, steroids, or biologics vs. a placebo. These studies provide evidence for a therapeutic role in microbiota manipulation in mild to moderate UC. FMT is a promising alternative or adjuvant modality to current therapies for UC patients. More extensive clinical trials are pending to confirm its long-term efficacies and safety [14, 25, 26, 62, 65, 66].

FMT in Crohn’s Disease

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of early case series of FMTs in Crohn’s disease showed clinical remissions of 50% [61]. However, RCT data are lacking. A recent randomized, sham-controlled pilot trial evaluating FMT in Crohn’s disease by Sokol et al. [67] did not achieve the primary endpoint of donor microbiota engraftment at week 6. However, it demonstrated that the post-FMT increase in alpha diversity was driven by the engraftment of donor species, mainly seen with Actinobacteria species associated with remission and Bacteroidetes in relapse. The failure of a single FMT application in this trial suggested that multiple transplantations may be needed [68, 69].

Current Observations of FMT in IBD

Overall, FMT is safe for patients with IBD. Most of the adverse effects were self-limiting GI complaints. Severe adverse effects were included in a few patients with worsening colitis, Clostridiodes infection, and pneumonia. Minor AEs were new anemia and elevated alkaline phosphatase, and aminotransferases were similar in both groups [14, 25, 26, 62, 64, 65, 67]. Although a few case reports suggest the effectiveness of FMT in pouchitis, the results of RCTs are still pending.

The efficacy of FMT depends on the severity of the disease, the delivery routes, and the duration of treatment. Multiple applications over a longer period can induce prolonged clinical remission [64, 65]. Both a shorter duration and a milder disease state in UC allowed for higher success. Concurrent use of corticosteroids and severe endoscopic disease may decrease response.

A meta-analysis showed that remission rates in the treatment of UC can vary depending on the route of administration. The lower GI route achieved the best remission rate [17]. While delivery via colonoscopy or enema showed better responses than duodenal infusions, oral lyophilized capsules have now proven to be an effective alternative [14, 25, 26, 64, 65].

The post-FMT intestinal flora of recipients generally increased in diversity and was enriched with species associated with eubiosis, even in cases where remission was not reached [17]. In addition to the restoration of the gut microbiome, improved insulin sensitivity was also observed when FMT from lean donors was used to treat obese recipients [10]. It has been reported that some combinations medications can influence the efficacy of FMT. A population-based metagenomic analysis showed significant associations between the gut microbiome and several drugs, such as antibiotics, proton-pump inhibitors, metformin, statins, and laxatives [70]. Antibiotic pretreatment may improve the efficacy of FMT in patients with UC [71], but early antibiotic use may increase the risk of FMT failure [72].

Microbial engraftment is an important factor for a successful FMT. Preconditioning the recipient’s gut flora with antibiotics before FMT could likely eliminate pathobionts such as Fusobacterium, Sutterella, Escherichia, and Streptococcus to facilitate the engraftment of beneficial microbes, resulting in clinical remissions [65]. A high abundance of Caudovirales in recipients can diminish FMT effectiveness [62, 73].

The efficacy of this approach may also be donor-dependent. There are some case series that exhibit positive results [74], but others show disappointing results [75], which can be partly explained by the donor characteristics, perhaps bacteriological or immunological. In a trial in 2015 using FMT from 6 donors to treat IBD, the donor-produced stool was significantly more effective than a placebo, while patients administered stool produced by the other 5 donors had similar response rates to placebo treatment [25]. The donor’s specimen characteristics may well create a super donor phenomenon [25, 36]. The components and viability of the donor’s fecal microbiota can affect FMT efficacy. Further efforts are needed to optimize the procedure for preparing donor feces.

FMT in MS

MS is an autoimmune neurologic disorder characterized pathologically by multifocal areas of demyelination with loss of oligodendrocytes and astroglial scarring. Moreover, there is a clinical presentation of gradual progression into significant physical disability within 20–25 years in more than 30% of patients [76]. Given that the gut microbiota and/or their metabolites contribute to shaping neurons [77], astrocytes [78], and microglia [79] of the CNS, it is not surprising that the gut microbiota is involved in the pathogenesis of MS. The microbiome, acting is an integral player in maintaining the microbiota-gut-brain axis, therefore, is a fundamental underlying mechanism of utilizing FMT in central nervous system (CNS) disease (Fig. 1) [80]. Ample evidence demonstrates the presence of gut microbiota dysbiosis in MS [81, 82], and re-establishing gut microbiota is considered a promising novel therapeutic strategy. Recent sequencing-based approaches have revealed that MS has a distinct gut microbiota composition compared to healthy controls [83]. A transplantation study of human fecal material in a mouse model of MS revealed that mice transplanted with MS patient-derived microbiota had a higher frequency of spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) than mice colonized with intestinal bacteria from healthy twins. More strikingly, mouse recipients of MS microbiota had a lower level of IL-10 produced by immune cells than mouse recipients of healthy samples, while neutralization of IL-10 in mice colonized with healthy fecal samples caused disease incidence to increase, indicating IL-10 may have a regulatory role in the pathogenesis of MS [84]. Similarly, Berer et al. reported concordance results showing that germ-free mice transplanted with microbiota from MS patients exhibited reduced proportions of IL-10+ Tregs compared with mice administered with microbiota from healthy controls. Further study on immunoregulatory mechanisms showed that MS-associated bacterial species decrease Tregs and increase Th1 lymphocyte differentiation in vitro and simultaneously exacerbate disease severity [84]. These studies provided the basis for the hypothesis that FMT can be a novel therapy by modulating the immune response in MS. A recent study reported that FMT can restore altered gut microbiota and have a therapeutic effect on EAE; the study also revealed that FMT prevented blood–brain barrier (BBB) leakage with protective effects on myelin and axons and also alleviated microglia and astrocyte activation [53], which were considered to contribute to the inflammatory pathology of MS [85]. Another study addressed the fact that FMT ameliorated the severity and pathologic outcomes of EAE disease partly due to modulating the composition of the gut microbiota by increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria and reducing the abundance of pathogenic bacteria [54]. Interventions with Clostridioides butyricum and norfloxacin can rebuild the composition of the gut microbiota and regulate the immune response in EAE mice by suppressing Th17 cell response and increasing Treg response via suppression of the MAPK pathway, eventually ameliorating EAE, indicating gut microbiota modulation is a potential efficacious therapy for MS [55]. Similarly, studies in human patients with MS have demonstrated that probiotics can ameliorate neuroinflammation. Several studies on human MS patients reported that administration of probiotics (enriched with Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and Bifidobacterium) can rebuild the gut microbiota, repress the inflammatory peripheral immune response with a negative correlation with pro-inflammatory markers, and afford a positive correlation with anti-inflammatory immune markers [56]. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial reported that administration of probiotics to MS patients can achieve favorable effects on an expanded disability status scale (EDSS), parameters of mental health, inflammatory factors, markers of insulin resistance, high-density lipoprotein (HDL-), total-/HDL cholesterol, and malondialdehyde levels, indicating that probiotic treatment can improve MS [86]. A phase 1b study (NCT03594487) is underway to evaluate the safety and benefits of treating progressive MS patients with capsules of the fecal microbiome.

FMT in Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the cutaneous, musculoskeletal, and GI systems. Recent studies have linked Th17 cells to several autoimmune disorder,s including psoriasis [87]. One proposed mechanism is based on the observation that T cells produce IL-17 in response to IL-23. It was found that IL-17R receptor and IL-17RA protein are more highly expressed in cases of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) when compared to asymptomatic patients as well as patients with joint pain secondary to osteoarthritis [87]. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (NCT03058900) is ongoing to determine if FMT is more effective than a placebo in reducing disease activity in patients with PsA and active peripheral arthritis concomitantly treated with weekly subcutaneously administered methotrexate. Thus far, participants with PsA in a nested qualitative study found FMT acceptable and safe [57, 88].

FMT in Autoimmune Arthritis

The effect of microbes on autoimmune arthritis was also addressed in germ-free mice. Wu and the team observed that markers for autoimmune arthritis are significantly reduced by the neutralization of IL-17 via interference with germinal center formation in GALT [89]. However, upon colonization of a species of segmented filamentous bacteria, autoimmune arthritis markers and autoantibodies were increased after Th17 cell proliferation [89]. These observations enhance our perspective on the etiological mechanisms and effects of microbiota in autoimmune arthritis and perhaps other autoimmune diseases.

FMT in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototypical autoimmune disorder characterized by the presence of hyperactive immune cells and aberrant antibody responses to nuclear and cytoplasmic antigens, multisystem inflammation, protean clinical manifestations, and a relapsing and remitting course that affects primarily young women [90]. Dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota is implicated in the development of SLE [91,92,93]. Patients with SLE have a restricted gut microbiota richness and diversity, with a significantly reduced Firmicutes/Bacteroides ratio [94,95,96]. The association between gut microbiome composition and disease activity was explored. Li et al. reported that the genera Streptococcus, Campylobacter, and Veillonella positively associated with lupus activity, while the genus Bifidobacterium negatively correlated with disease activity [94]. Interestingly, another study demonstrated that the increase genera in Bacteroides, Bilophila, Parabacteroides, and Succinivibrio in SLE were positively correlated with the levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-17, IL-21, IL-2R, TWEAK, IL-35, IFN-γ, and IL-10, whereas the decrease in genera such as Dialister and Gemmiger was inversely correlated with the levels of IL-17, IL-2R, and IL-35 in SLE patients. Furthermore, this study also corroborated that glucocorticoid therapy may stabilize the gut microbiota environment, modify the metabolic function of the gut microbiota, and further reduce inflammatory cytokine production [95]. The abundance of Ruminococcus gnavus of the Lachnospiraceae family was also found to be fivefold higher in SLE patients compared to healthy controls [97]. Subsequently, Chen et al. demonstrated that there was a disrupted gut microbiota with a distinct functional profile in SLE patients, which is similar to the lupus MLR/lpr mouse model [98]. Germ-free mice receiving FMT from SLE patients developed lupus-like phenotypic features of autoimmunity and inflammation, indicating a causal role of gut dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of SLE [99]. Normal mice administered fecal microbiome from SLE mice resulted in an exacerbation of the intestinal mucosal splenic immune response as well as the upregulation of certain lupus susceptibility genes in their colon, suggesting SLE is associated with aberrant gut microbiota [55]. Another study in MRL/lpr mice established that FMT alleviated lupus severity by renovating the antibiotic-induced dysbiosis of gut microbiota [100]. Collectively, these observations affirm the important roles of gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of SLE. Hence, the manipulation of gut microbiota is a logical and promising novel therapeutic strategy for SLE. At present, gut microbiota intervention in SLE is still in the beginning stages. The first clinical trial of FMT in active SLE patients (ChiCTR2000036352) demonstrated that FMT may be a feasible, safe, and potentially effective short-term treatment for patients with SLE by altering the gut microbiota and its metabolic profile. It effectively changed the gut microbiota from a pro-inflammatory style to an anti-inflammatory style and also improved clinical parameters [58]. FMT in SLE is still in its infancy as data are still sparse and further studies with large multi-center cohorts are warranted.

FMT in T1D

T1D is an autoimmune disease characterized by T-cell-mediated beta-cell destruction, and its pathophysiology has been linked to intestinal dysbiosis [101]. FMT studies in NOD mice suggested that the interplay of gut microbiota and immune players is involved in the pathophysiology of T1D. In a randomized controlled trail conducted in the Netherlands (NTR3697), patients with recent onset of T1D were randomized into two groups (n = 10 per group) and were administered with either autologous or allogenic healthy donors FMT [59]. The data showed that FMT can stabilize residual beta cell function in subjects with new-onset T1D. Interestingly, the effect of autologous FMT is better than allogenic FMT.

FMT in Autism Spectrum Disorders

Interactions between the GI tract and the CNS have long been observed, and recent studies support a link between microbiota and CNS disease. SCFAs and other microbe metabolites play a direct role in communication along the gut-brain axis by acting as neurotransmitters.

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are complex neurobiological disorders of unknown cause. Reports on abnormal gut bacteria and GI problems in children with ASD suggested that microbiome dysbiosis may be linked to ASD. Interestingly, there is increasing evidence of autoimmune phenomena in some individuals with autism [102,103,104]. In an open-label study, 18 children with ASD and moderate to severe GI problems were enrolled and received FMT derived from stools obtained from healthy individuals for 10 week, followed by an 8-week follow-up observation period [31]. This study also compared two routes of administration, oral vs. rectal, for the initial dose and thereafter, with a lower maintenance dosage given orally for 7–8 weeks. Improvements in GI symptoms, ASD symptoms, and the microbiome persisted for at least 8 weeks after treatment ended in children who received FMT. Moreover, the ASD bacterial community also shifted toward that of age/gender-matched healthy controls and to that of their donors (NCT02504554). Recently, Li et al. reported their findings from an open-label clinical study of FMT in children with ASD [60]. Their data showed that: (i) there was a large difference in baseline characteristics of behavior, GI symptoms, and gut microbiota between children with ASD and controls; (ii) ASD showed improvement in GI symptoms like abdominal pain, constipation, or diarrhea; (iii) in addition to GI symptoms, ASD symptoms were also improved after FMT treatment; (iv) FMT promoted the colonization of donor microbes and shifted the microbiota of children with ASD toward that of the donors. However, in this study, the beneficial effect on GI symptoms and ASD gradually diminished within a few weeks at the end of therapy, suggesting that extended treatment with FMT is needed (Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (www.chictr.org.cn) (trial registration number ChiCTR1800014745). Follow-up randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies will be necessary to determine the efficacy of FMT on children with ASD, and GI problems should include immunological parameters on autoimmunity and autism.

FMT in Cancer

The use of targeted immunotherapies to indirectly increase T-cell activation and boost the antitumor response is a strategic approach in cancer treatment. Anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) antibodies are immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that do not directly cause tumor cell death but rather lead to activation of anti-tumor pathways and T-cell immune response [105]. Patients exhibit different responses to the treatments. It was found that patients vary in microbiome composition and that patients who responded better to PD-1 ICI had a much more diverse microbiota than those who did not respond to treatment [8]. It was also observed that Ruminococcus obeum was more prevalent among ICI-responsive melanoma patients compared to Roseburia intestinalis in groups that did not respond to the treatment [105]. Additionally, the specific strains and relative abundances were shown to vary between patients with different cancers. The microbiome composition is also associated with varying T-cell responses and efficacy [105]. Studies comparing antitumor responses in antibiotic-treated vs. control mouse populations suggest that loss of commensal microbiota negatively affects the efficacy of ICI [105]. Patients pretreated with antibiotics were found to have a poorer response to ICI [106]. As such, replenishment of beneficial strains may be sufficient to improve patient outcomes. FMT has already been shown to modulate antitumor immunity and response to this targeted immunotherapy. There is evidence that some commensal microbes increase response to therapies that target ICIs, and that restoration of these strains is necessary for anti-tumor action. The mechanism is still under investigation, but it is postulated that metabolites secreted by these GI microbes may affect how cancerous cells respond to apoptosis-inducing agents [107].

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a blood cancer that is treated by chemotherapeutic agents that, as a consequence, deplete the cells involved in the immune response and infection defense. Patients often require multiple antibiotic treatments due to secondary infections, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is not always possible. Restoration of the gut microbiome is thought to not only protect against the overgrowth of pathogenic strains but also improve the efficacy of the treatments while reducing complications. A study of AML patients treated with autologous FMT showed improved outcomes post-treatment compared to control patients [108].

Mechanisms and Outlook of FMT in Cancer

While studies on viral etiology in cancer are abundant, the exact mechanisms by which bacteria and other microorganisms trigger tumorigenesis are limited. One study showed that tumor cells undergo apoptosis when microbiota diversity increases and SCFA levels are restored, suggesting that dysbiosis and the resulting metabolic dysregulation play a role [5]. Recent studies in colorectal cancer indicate that chronic inflammation caused by pathogenic metabolites leading to sustained tissue damage is responsible for an increased rate of mutation and resultant neoplasia [109, 110]. This pathogenesis is also supported by the phenomenon of gastric cancer development secondary to H. pylori infection. Research shows that the chronic gastric inflammation resulting from infection eventually develops into gastric carcinoma [12].

“Leaky gut,” secondary to GI dysbiosis, occurs when the intestinal barrier is damaged or weakened and permeability increases. The overgrowth of harmful bacteria also results in an increase in damaging metabolites that can then affect other parts of the body. Studies on the liver-gut axis found that metabolite trafficking via the portal system causes damage to the liver. The resultant inflammation and loss of immune tolerance precipitate carcinogenesis. It was found that cytokines released in the GI tract in response to dysbiosis affected the liver downstream by promoting hepato-carcinogenesis and migration of cancerous cells [107]. It was observed that cancerous tissues also have their own microbiomes. Similar to how a different microenvironment is detected in different tissues and systems of the body, different tumors have varying microenvironments that depend on their specific characteristics. For example, the low oxygen environment of tumors allows for the proliferation of anaerobic strains, and inflammation and edema support the movement of bacteria in and around the tissue. Tumors in the mucosa are constantly exposed to microorganisms and, as such, can be greatly influenced by the microbiota [5]. Research shows that certain strains of intratumor bacteria contribute to drug resistance by directly metabolizing chemotherapeutic agents and that these effects can be reversed with antibiotic administration [111].

Given the implication of microbiota dysregulation in many inflammatory, infectious, and metabolic diseases and the interplay of the microbiome and host health processes, FMT is regarded as a strategic way to target both the root cause as well as alleviate the symptoms. There were concerns about the potential risk of infection to the oncological patient population since clinical trials and research were typically done with non-immunocompromised individuals and there is no long-term safety data [107, 112]. However, recent data suggest that the benefits from the restoration of microbiota come without added risks to the patient population. Reversal of dysbiosis comes with an increase in antimicrobial peptides, restoration of mucosal barrier and immunity, as well as reestablishment of expected immune signaling pathways [112]. Additionally, the protective effects of a diverse microbiome include resistance to pathogenic colonization and a decrease in the risk of infectious complications. As such, successful treatment by FMT would improve outcomes in these populations. Clinically, microbial intervention would further benefit oncologic patients by managing acute toxicity or secondary complications. Indeed, complications of cancer therapy include diarrhea and other GI toxicities.

FMT can also be a promising adjuvant therapy for cancer patients who do not respond to immune checkpoint-targeted chemotherapeutic drugs [113]. This is well illustrated in cancer patients who do not respond to anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 [114], including both primary and secondary resistance [115, 116]. In the phase I clinical trial, FMT of stool microbes from responders together with anti-PD-1 therapy in patients with anti-PD-1-refractory metastatic melanoma shifted the microbiota of recipients toward a responsive donor-type taxonomic composition, reset the tumor microenvironment with upregulation of MHC class II molecules in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and decreased inflammatory markers in the plasma. These observations clearly illustrate how modulating gut microbiota can overcome resistance to immunotherapy [117, 118]. Wang et al. showed that FMT improved immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-associated colitis in cancer patients and was accompanied by the reconstitution of gut microbiota and a relative increase in the proportion of regulatory T-cells within the colonic mucosa [119]. A study on FMT in humans and mice clearly illustrated that the efficacy of CTLA-4 blockade relies on the composition of the gut microbiota (B. fragilis and/or B. thetaiotaomicron and Burkholderiales) [120] and further highlighted the potential of FMT to alleviate the side effects of cancer treatment. Physiologically, FMT can modulate the diversity of commensals to that of the responder and facilitates maintaining intestinal tissue vigor, amelioration of bile acid metabolism, and maturation of the mucosal immune system. Moreover, FMT could transfer distinct commensals that can mediate immune activation to chemotherapy drugs during concomitant immunotherapy [121]. Iida et al. reported that an intact commensal microbiota enabled optimal response to cancer treatment by regulating myeloid-derived cells in the tumor microenvironment [122]. Chang et al. established that FMT after 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) treatment in colorectal cancer-bearing mice restored the disrupted fecal gut microbiota composition, attenuated FOLFOX-induced intestinal mucositis, and alleviated the expression of toll-like receptors (TLRs), MyD88, and serum IL-6, which can be induced after FOLFOX treatment. The possible mechanism may be related to the TLR-MyD88-NF-κB signaling pathway [123].

In addition to direct interaction with immune cells, anticancer immunity can also be regulated by microbial metabolites. Recent studies revealed that microbiota-derived SCFAs could enhance the memory potential of antigen-activated CD8+ T cells [124], and the microbial metabolite butyrate could promote antitumor therapeutic efficacy through the inhibition of DNA-binding 2-dependent regulation of CD8+ T-cell immunity [125]. Secondary bile acid-mediated gut dysbiosis promotes intestinal carcinogenesis in that it may disrupt the integrity of the intestinal barrier, promote the recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages and polarization of M2 macrophages, and further accelerate the intestinal adenoma-adenocarcinoma sequence by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [126]. Bile acid receptors play a critical role in colorectal cancer, and FMT can restore normal fecal bile acid composition in rCDI [48]. Therefore, it is reasonable that targeting the bile acids–microbiota axis by FMT should be a potential intervention for colorectal cancer management [127]. Studies also show that targeting the microbiota in conjunction with chemotherapy attenuates side effects such as neutropenia [107]. Collectively, the mechanism of microbiota modulation on immunotherapy response in cancer patients is complex and involves the interplay of immune cells, microbial metabolites, anticancer drugs, and the tumor microenvironment [128]. Though the direct mechanisms of FMT in cancer are still under investigation, it is believed that supporting the microbiota will decrease inflammatory mechanisms, prevent colonization by pathogenic strains, and reduce injury and dysfunction (Fig. 3). Probiotic therapies were explored and found to be insufficient in both diversity and density to effectively restore or preserve the microbiome [112]. Although FMT has been shown to successfully restore diversity and number to the microbiome in patients with dysbiosis secondary to antibiotic use as well as in patients with C. difficile and other diseases, more work remains to be done on the immunocompromised oncologic population [107]. Finally, further understanding of microbiota-modulating mechanisms in oncogenesis will help in determining the strategy, safety, and efficacy of FMT for different types of cancer.

Mechanisms involved in the efficacy of FMT in cancer therapy. The mechanism of FMT in cancer therapy is multifactorial, such as increasing microbial diversity, enhancing the resistance to pathogenic colonization, maintaining mucosal integrity, modulation of the immune system, and regulation of microbial metabolites. Collectively, the interplay of these factors reset the tumor microenvironment, improves the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs, and reduces tissue injury

Future Perspectives of FMT in Human Medicine

Although FMT has gained much attention recently and has increased its potential applications on top of GI disease, there are still many lingering issues that limit its application in clinical settings. Notably, the US FDA recently issued several warnings on FMT following serious infections and one death after FMT [123, 129].

The major issue of FMT is: What do we know/do not know about the baseline microbial load/functional output and its long-term physiological effects on the FMT recipient? The genetic make-up, interplay of diet and microbial metabolites, drugs/medications, and other underlying diseases of the individual can interfere with the clinical outcome of FMT [130, 131]. The dynamics of microbial strains in engraftment processes and species interdependency add another compounding level of factors that are relevant to FMT efficacy. Understanding the diversity and variability of individual microbiome differences is of vital importance in FMT [132].

Feces are a highly complex matrix comprising hundreds, if not thousands, of species of microorganisms, microbial metabolites, and other stool ingredients that are highly variable between different people. Variability also occurs with different time points, even in the same individual. Hence, there is a lack of standardization of human stool, and stool-derived products can result in significant variation between different batches of FMT products. Fundamental parameters such as donor screening, methods of preparation, the amount of starting material, and the route of administration need to be better defined [133,134,135,136].

Furthermore, even though donors may appear healthy and asymptomatic of infections, they may carry pathogens that are harmful to FMT recipients. With the alarming report of the serious effect on two immunocompromised FMT recipients who received fecal material from a donor who was found to have extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli [137], the FDA has now required in-depth screening to include the use of nucleic acid amplification tests for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase microorganism before FMT [138]. An extra screening process has been instituted since the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The FDA issued updated safety protection guidelines specific to COVID-19 in 2020 [139]. Thus, proper handling of FMT material for safety and quality control is of utmost importance to prevent contamination of pathogens. FMT materials should meet Good Manufacturing Practice (GFP) criteria established for pharmaceutical practice with accurate pathogen screening and detection methods. In addition to GFP requirements, methods of preparation of fecal materials for FMT can affect its efficacy. Fresh collected and frozen fecal materials showed similar efficacies in CDI treatment [18, 140, 141] and IBD [142, 143].

Pretreatment with antibiotics has also been considered, and data show increased IBD remission rates when antibiotics are given prior to FMT [11]. Some patients can experience mild to moderate side effects after FMT that range from GI discomfort to anesthetic complications.

For each method, clinicians offer informed consent, laying out a clear understanding of the procedure, associated risks, aesthetic factors, privacy, psychological factors, and the management plan. Various routes of FMT administration are also being investigated for their efficacy and safety. Administration of FMT in the GI tract can be via the upper, mid-, or lower gut (Fig. 4), and each comes with different financial and practical considerations. Studies have shown effective treatment of rCDI via both nasoduodenal and colonoscopic FMT administration, but there is no standard protocol. A 2017 study on the use of both the oral route and the colonoscopy route FMT in treating a patient with rCDI in a RCT showed similar efficacy in preventing recurrent infection over 12 weeks [144]. In this study, 116 adult patients with rCDI were enrolled and randomly assigned to FMT by capsule or by colonoscopy at a 1:1 ratio. Prevention of rCDI after a single treatment was achieved in 96.2% of both the capsule group (51/53) and the colonoscopy group (50/52). The rates of minor adverse events were 5.4% and 12.5% for the capsule group and the colonoscopy group, respectively.

Routes of FMT administration. FMT can be administered through the upper gut (mouth or nose), mid-gut (tube or surgical procedure), or lower gut (anus). In detail, the route through the upper gut includes oral intake, a nasogastric tube (NGT), esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), and enteroscopy. The route through the mid-gut encompasses the nasojejunal/enteral tube, jejunostomy, and percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy (PEC). The route through the lower gut includes enteroscopy, transendoscopic enteral tube (TET), sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy enema, and distal ileum stoma/colostomy

The efficacy of FMT is also different between gut infection disease and non-gut infection disease. FMT is very effective in treating luminal infection, as exemplified by Clostridiodes difficile infection [73]. However, its effectiveness in non-CDI indications such as IBD can differ. Mechanistically, newly FMT-introduced microorganisms may indirectly inhibit Clostridioides difficile by competing for nutrients or by enhancing host innate immune defenses such as antimicrobial peptides in rCDI [66, 145, 146]. Bacterial metabolites such as levels of indole and secondary bile acids have also been implicated to have predictive value of positive FMT outcome in rCDI and UC, respectively [147, 148]. FMT can replenish clostridial clusters XIVA and IV for the recipient. These microbes possess 7-dehydroxylase activity that converts primary bile salts to secondary bile salts and deoxycholic acid that inhibits C. difficile sporulation [149, 150]. Furthermore, other factors such as the contribution of other commensal nonbacterial microbial populations of fungi, bacteriophages, viruses, and parasites in terms of diversity, composition, and their metabolites in determining the efficacy of FMT are limited and remain to be further investigated [151,152,153]. Further studies are needed to improve and maintain a sustained response.

In addition, data from amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics have consistently shown that increases in alpha diversity (number of different species within the community) and shifts in beta diversity (composition) towards the donor microbiota could be indicators of FMT success before therapy [154]. An extensive study on specific microbial diversity, composition, and functional output by targeted and untargeted metabolite profiling with artificial intelligence will help in designing personalized FMT in the future [155]. Recently, FMT was explored as a way to alleviate GI symptoms and improve the immune response in patients who recovered from COVID-19. Fecal samples were analyzed and found to be positive for SARS-CoV2 in half of the patients, suggesting that the GI tract is implicated in the viral process in some way. It was found that COVID-19 patients had very different microbiota compositions compared to controls, with changes persisting even after discharge. In a recent study, 11 COVID-positive patients underwent FMT. The findings show restoration of microbiota composition to baseline, and the 5 patients with GI complaints reported improvement in their symptoms [156]. They also used flow cytometry to study the effects of FMT on leukocyte composition. The study was notable for an increase in memory B cells with an associated decrease in naïve B cells, as well as a relative increase in double-positive T cells. These initial findings suggest modulation of the gut microbiome favors improved immune response in cases of viral infection, but more work remains to be done [156].

Despite the lack of knowledge about the precise mechanisms of action and pharmacological standardization of FMT, its use in clinical practice has piqued the interest of patients, clinicians, and researchers alike. Much effort is needed to unveil the mechanisms and continue to update the FMT guidelines internationally [157,158,159]. With technological advances and the continuous development of artificial intelligence in personalized medicine, it is the goal of scientists, clinicians, and patient communities that FMT will become a standardized treatment where the current regimen will be replaced by well-defined microbial consortia, metabolites, or laboratory-synthesized compounds that can be readily administered.

Abbreviations

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- ASD:

-

Autism spectrum disorder

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CTLA-4:

-

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4

- EAE:

-

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- FMT:

-

Fecal microbiota transplantation

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- ICIs:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- IND:

-

Investigational new drug

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- NNT:

-

Number needed to treat

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death protein-1

- PsA:

-

Psoriatic arthritis

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- rCDI:

-

Recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection

- SCFAs:

-

Short-chain fatty acids

- SLE:

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- T1D:

-

Type 1 diabetes

- UC:

-

Ulcerative colitis

References

Dominguez-Bello MG, Godoy-Vitorino F, Knight R, Blaser MJ (2019) Role of the microbiome in human development. Gut 68:1108–1114. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317503

Mohajeri MH, Brummer RJM, Rastall RA, Weersma RK, Harmsen HJM, Faas M, Eggersdorfer M (2018) The role of the microbiome for human health: from basic science to clinical applications. Eur J Nutr 57:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1703-4

Barko PC, McMichael MA, Swanson KS, Williams DA (2018) The gastrointestinal microbiome: a review. J Vet Intern Med 32:9–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.14875

Giles EM, Couper J (2020) Microbiome in health and disease. J Paediatr Child Health 56:1735–1738. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14939

Picardo SL, Coburn B, Hansen AR (2019) The microbiome and cancer for clinicians. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 141:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.06.004

Quigley EM (2013) Gut bacteria in health and disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 9:560–569

Illiano P, Brambilla R, Parolini C (2020) The mutual interplay of gut microbiota, diet and human disease. FEBS J 287:833–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15217

Gomaa EZ (2020) Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: a review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 113:2019–2040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-020-01474-7

Littman DR, Pamer EG (2011) Role of the commensal microbiota in normal and pathogenic host immune responses. Cell Host Microbe 10:311–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.004

Vindigni SM, Surawicz CM (2017) Fecal microbiota transplantation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 46:171–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2016.09.012

Collins M, DeWitt M (2020) Fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of Crohn disease. JAAPA 33:34–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JAA.0000694964.31958.b9

Rajagopala SV, Vashee S, Oldfield LM, Suzuki Y, Venter JC, Telenti A, Nelson KE (2017) The human microbiome and cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 10:226–234. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0249

Myers B, Brownstone N, Reddy V, Chan S, Thibodeaux Q, Truong A, Bhutani T, Chang HW, Liao W (2019) The gut microbiome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 33:101494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2020.101494

Costello SP, Hughes PA, Waters O, Bryant RV, Vincent AD, Blatchford P, Katsikeros R, Makanyanga J, Campaniello MA, Mavrangelos C, Rosewarne CP, Bickley C, Peters C, Schoeman MN, Conlon MA, Roberts-Thomson IC, Andrews JM (2019) Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on 8-week remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 321:156–164. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.20046

Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, Kauvar AJ (1958) Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery 44:854–859

Hentges DJ, Freter R (1962) In vivo and in vitro antagonism of intestinal bacteria against Shigella flexneri. I. Correlation between various tests. J Infect Dis 110:30–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/110.1.30

Fang H, Fu L, Wang J (2018) Protocol for fecal microbiota transplantation in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2018:8941340. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8941340

Hamilton MJ, Weingarden AR, Sadowsky MJ, Khoruts A (2012) Standardized frozen preparation for transplantation of fecal microbiota for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol 107:761–767. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.482

Youngster I, Russell GH, Pindar C, Ziv-Baran T, Sauk J, Hohmann EL (2014) Oral, capsulized, frozen fecal microbiota transplantation for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA 312:1772–1778. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.13875

Cui B, Li P, Xu L, Peng Z, Xiang J, He Z, Zhang T, Ji G, Nie Y, Wu K, Fan D, Zhang F (2016) Step-up fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) strategy. Gut Microbes 7:323–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1151608

Feuerstadt P, Louie TJ, Lashner B, Wang EEL, Diao L, Bryant JA, Sims M, Kraft CS, Cohen SH, Berenson CS, Korman LY, Ford CB, Litcofsky KD, Lombardo MJ, Wortman JR, Wu H, Auniņš JG, McChalicher CWJ, Winkler JA, McGovern BH, Trucksis M, Henn MR, von Moltke L (2022) SER-109, an oral microbiome therapy for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. N Engl J Med 386:220–229. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2106516

Bennet JD, Brinkman M (1989) Treatment of ulcerative colitis by implantation of normal colonic flora. Lancet 1:164. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91183-5

Borody TJ, George L, Andrews P, Brandl S, Noonan S, Cole P, Hyland L, Morgan A, Maysey J, Moore-Jones D (1989) Bowel-flora alteration: a potential cure for inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome? Med J Aust 150:604. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb136704.x

Vrieze A, Van Nood E, Holleman F, Salojarvi J, Kootte RS, Bartelsman JF, Dallinga-Thie GM, Ackermans MT, Serlie MJ, Oozeer R, Derrien M, Druesne A, Van Hylckama Vlieg JE, Bloks VW, Groen AK, Heilig HG, Zoetendal EG, Stroes ES, de Vos WM, Hoekstra JB, Nieuwdorp M (2012) Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology 143:913–6.e7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.031

Moayyedi P, Surette MG, Kim PT, Libertucci J, Wolfe M, Onischi C, Armstrong D, Marshall JK, Kassam Z, Reinisch W, Lee CH (2015) Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 149:102–9.e6. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.001

Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, Tijssen JG, Hartman JH, Duflou A, Lowenberg M, van den Brink GR, Mathus-Vliegen EM, de Vos WM, Zoetendal EG, D’Haens GR, Ponsioen CY (2015) Findings from a randomized controlled trial of fecal transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 149:110–8.e4. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.045

Tian H, Ding C, Gong J, Ge X, McFarland LV, Gu L, Wei Y, Chen Q, Zhu W, Li J, Li N (2016) Treatment of slow transit constipation with fecal microbiota transplantation: a pilot study. J Clin Gastroenterol 50:865–870. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000472

Kakihana K, Fujioka Y, Suda W, Najima Y, Kuwata G, Sasajima S, Mimura I, Morita H, Sugiyama D, Nishikawa H, Hattori M, Hino Y, Ikegawa S, Yamamoto K, Toya T, Doki N, Koizumi K, Honda K, Ohashi K (2016) Fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with steroid-resistant acute graft-versus-host disease of the gut. Blood 128:2083–2088. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-05-717652

Kao D, Roach B, Park H, Hotte N, Madsen K, Bain V, Tandon P (2016) Fecal microbiota transplantation in the management of hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology 63:339–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28121

He Z, Cui BT, Zhang T, Li P, Long CY, Ji GZ, Zhang FM (2017) Fecal microbiota transplantation cured epilepsy in a case with Crohn’s disease: The first report. World J Gastroenterol 23:3565–3568. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i19.3565

Kang DW, Adams JB, Gregory AC, Borody T, Chittick L, Fasano A, Khoruts A, Geis E, Maldonado J, McDonough-Means S, Pollard EL, Roux S, Sadowsky MJ, Lipson KS, Sullivan MB, Caporaso JG, Krajmalnik-Brown R (2017) Microbiota transfer therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome 5:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0225-7

Watane A, Cavuoto KM, Rojas M, Dermer H, Day JO, Banerjee S, Galor A (2022) Fecal microbial transplant in individuals with immune-mediated dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol 233:90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2021.06.022

Kassam Z, Lee CH, Yuan Y, Hunt RH (2013) Fecal microbiota transplantation forClostridium difficile infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 108:500–508

Gough E, Shaikh H, Manges AR (2011) Systematic review of intestinal microbiota transplantation (fecal bacteriotherapy) for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 53:994–1002. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir632

Drekonja D, Reich J, Gezahegn S, Greer N, Shaukat A, MacDonald R, Rutks I, Wilt TJ (2015) Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 162:630–638. https://doi.org/10.7326/m14-2693

Van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, Fuentes S, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, Visser CE, Kuijper EJ, Bartelsman JF, Tijssen JG (2013) Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 368:407–415

Hvas CL, Dahl Jørgensen SM, Jørgensen SP, Storgaard M, Lemming L, Hansen MM, Erikstrup C, Dahlerup JF (2019) Fecal microbiota transplantation is superior to fidaxomicin for treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology 156:1324–32.e3. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.019

Seekatz AM, Theriot CM, Molloy CT, Wozniak KL, Bergin IL, Young VB (2015) Fecal microbiota transplantation eliminates Clostridium difficile in a murine model of relapsing disease. Infect Immun 83:3838–3846. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00459-15

Lawley TD, Clare S, Walker AW, Stares MD, Connor TR, Raisen C, Goulding D, Rad R, Schreiber F, Brandt C, Deakin LJ, Pickard DJ, Duncan SH, Flint HJ, Clark TG, Parkhill J, Dougan G (2012) Targeted restoration of the intestinal microbiota with a simple, defined bacteriotherapy resolves relapsing Clostridium difficile disease in mice. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002995. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002995

Buffie CG, Bucci V, Stein RR, McKenney PT, Ling L, Gobourne A, No D, Liu H, Kinnebrew M, Viale A, Littmann E, van den Brink MR, Jenq RR, Taur Y, Sander C, Cross JR, Toussaint NC, Xavier JB, Pamer EG (2015) Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature 517:205–208. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13828

Zainah H, Hassan M, Shiekh-Sroujieh L, Hassan S, Alangaden G, Ramesh M (2015) Intestinal microbiota transplantation, a simple and effective treatment for severe and refractory Clostridium difficile infection. Dig Dis Sci 60:181–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-014-3296-y

Kelly CR, Ihunnah C, Fischer M, Khoruts A, Surawicz C, Afzali A, Aroniadis O, Barto A, Borody T, Giovanelli A, Gordon S, Gluck M, Hohmann EL, Kao D, Kao JY, McQuillen DP, Mellow M, Rank KM, Rao K, Ray A, Schwartz MA, Singh N, Stollman N, Suskind DL, Vindigni SM, Youngster I, Brandt L (2014) Fecal microbiota transplant for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection in immunocompromised patients. Am J Gastroenterol 109:1065–1071. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.133

Khoruts A, Sadowsky MJ (2016) Understanding the mechanisms of faecal microbiota transplantation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 13:508–516. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2016.98

Seekatz AM, Rao K, Santhosh K, Young VB (2016) Dynamics of the fecal microbiome in patients with recurrent and nonrecurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Genome Med 8:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-016-0298-8

Seekatz AM, Aas J, Gessert CE, Rubin TA, Saman DM, Bakken JS, Young VB (2014) Recovery of the gut microbiome following fecal microbiota transplantation. mBio 5:e00893-e914. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00893-14

Lenski RE, Riley MA (2002) Chemical warfare from an ecological perspective. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99:556–558

Weingarden AR, Dosa PI, DeWinter E, Steer CJ, Shaughnessy MK, Johnson JR, Khoruts A, Sadowsky MJ (2016) Changes in colonic bile acid composition following fecal microbiota transplantation are sufficient to control Clostridium difficile germination and growth. PLoS ONE 11:e0147210. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147210

Weingarden AR, Chen C, Bobr A, Yao D, Lu Y, Nelson VM, Sadowsky MJ, Khoruts A (2014) Microbiota transplantation restores normal fecal bile acid composition in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 306:G310–G319. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00282.2013

Vaishnava S, Yamamoto M, Severson KM, Ruhn KA, Yu X, Koren O, Ley R, Wakeland EK, Hooper LV (2011) The antibacterial lectin RegIIIgamma promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine. Science 334:255–258. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1209791

El Feghaly RE, Stauber JL, Deych E, Gonzalez C, Tarr PI, Haslam DB (2013) Markers of intestinal inflammation, not bacterial burden, correlate with clinical outcomes in Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 56:1713–1721. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit147

Staley C, Kaiser T, Vaughn BP, Graiziger CT, Hamilton MJ, Rehman TU, Song K, Khoruts A, Sadowsky MJ (2018) Predicting recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection following encapsulated fecal microbiota transplantation. Microbiome 6:166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0549-6

Suskind DL, Singh N, Nielson H, Wahbeh G (2015) Fecal microbial transplant via nasogastric tube for active pediatric ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 60:27–29. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000544

Li K, Wei S, Hu L, Yin X, Mai Y, Jiang C, Peng X, Cao X, Huang Z, Zhou H, Ma G, Liu Z, Li H, Zhao B (2020) Protection of fecal microbiota transplantation in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Mediators Inflamm 2020:2058272. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2058272

Wang S, Chen H, Wen X, Mu J, Sun M, Song X, Liu B, Chen J, Fan X (2021) The efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: transcriptome and gut microbiota profiling. J Immunol Res 2021:4400428. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4400428

Chen H, Ma X, Liu Y, Ma L, Chen Z, Lin X, Si L, Ma X, Chen X (2019) Gut microbiota interventions with clostridium butyricum and norfloxacin modulate immune response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Front Immunol 10:1662. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01662

Tankou SK, Regev K, Healy BC, Cox LM, Tjon E, Kivisakk P, Vanande IP, Cook S, Gandhi R, Glanz B, Stankiewicz J, Weiner HL (2018) Investigation of probiotics in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 24:58–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517737390

Kragsnaes MS, Kjeldsen J, Horn HC, Munk HL, Pedersen JK, Just SA, Ahlquist P, Pedersen FM, de Wit M, Moller S, Andersen V, Kristiansen K, Kinggaard Holm D, Holt HM, Christensen R, Ellingsen T (2021) Safety and efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for active peripheral psoriatic arthritis: an exploratory randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 80:1158–1167. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219511

Huang C, Yi P, Zhu M, Zhou W, Zhang B, Yi X, Long H, Zhang G, Wu H, Tsokos GC, Zhao M, Lu Q (2022) Safety and efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation for treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: an EXPLORER trial. J Autoimmun 130:102844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102844

de Groot P, Nikolic T, Pellegrini S, Sordi V, Imangaliyev S, Rampanelli E, Hanssen N, Attaye I, Bakker G, Duinkerken G, Joosten A, Prodan A, Levin E, Levels H, Potter van Loon B, van Bon A, Brouwer C, van Dam S, Simsek S, van Raalte D, Stam F, Gerdes V, Hoogma R, Diekman M, Gerding M, Rustemeijer C, de Bakker B, Hoekstra J, Zwinderman A, Bergman J, Holleman F, Piemonti L, De Vos W, Roep B, Nieuwdorp M (2021) Faecal microbiota transplantation halts progression of human new-onset type 1 diabetes in a randomised controlled trial. Gut 70:92–105. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322630

Li N, Chen H, Cheng Y, Xu F, Ruan G, Ying S, Tang W, Chen L, Chen M, Lv L, Ping Y, Chen D, Wei Y (2021) Fecal microbiota transplantation relieves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms by improving the gut microbiota in an open-label study. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11:759435. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.759435

Paramsothy S, Paramsothy R, Rubin DT, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, Mitchell HM, Castano-Rodriguez N (2017) Faecal microbiota transplantation for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis 11:1180–1199. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx063

Kellermayer R (2019) Fecal microbiota transplantation: great potential with many challenges. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 4:40. https://doi.org/10.21037/tgh.2019.05.10

Lee M, Chang EB (2021) Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and the microbiome-searching the crime scene for clues. Gastroenterology 160:524–537. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.056

Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, Walsh AJ, van den Bogaerde J, Samuel D, Leong RWL, Connor S, Ng W, Paramsothy R, Xuan W, Lin E, Mitchell HM, Borody TJ (2017) Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 389:1218–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30182-4

Haifer C, Paramsothy S, Kaakoush NO, Saikal A, Ghaly S, Yang T, Luu LDW, Borody TJ, Leong RW (2022) Lyophilised oral faecal microbiota transplantation for ulcerative colitis (LOTUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 7:141–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00400-3

Baktash A, Terveer EM, Zwittink RD, Hornung BVH, Corver J, Kuijper EJ, Smits WK (2018) Mechanistic insights in the success of fecal microbiota transplants for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infections. Front Microbiol 9:1242. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01242

Sokol H, Landman C, Seksik P, Berard L, Montil M, Nion-Larmurier I, Bourrier A, Le Gall G, Lalande V, De Rougemont A, Kirchgesner J, Daguenel A, Cachanado M, Rousseau A, Drouet E, Rosenzwajg M, Hagege H, Dray X, Klatzman D, Marteau P, Saint-Antoine IBDN, Beaugerie L, Simon T (2020) Fecal microbiota transplantation to maintain remission in Crohn’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled study. Microbiome 8:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-0792-5

Kong L, Lloyd-Price J, Vatanen T, Seksik P, Beaugerie L, Simon T, Vlamakis H, Sokol H, Xavier RJ (2020) Linking strain engraftment in fecal microbiota transplantation with maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 159:2193–202.e5. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.045

Shepherd ES, DeLoache WC, Pruss KM, Whitaker WR, Sonnenburg JL (2018) An exclusive metabolic niche enables strain engraftment in the gut microbiota. Nature 557:434–438. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0092-4

Zhernakova A, Kurilshikov A, Bonder MJ, Tigchelaar EF, Schirmer M, Vatanen T, Mujagic Z, Vila AV, Falony G, Vieira-Silva S, Wang J, Imhann F, Brandsma E, Jankipersadsing SA, Joossens M, Cenit MC, Deelen P, Swertz MA, Weersma RK, Feskens EJ, Netea MG, Gevers D, Jonkers D, Franke L, Aulchenko YS, Huttenhower C, Raes J, Hofker MH, Xavier RJ, Wijmenga C, Fu J (2016) Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity. Science 352:565–569. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad3369

Keshteli A, Millan B, Madsen K (2017) Pretreatment with antibiotics may enhance the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Mucosal Immunol 10:565–566

Allegretti JR, Kao D, Sitko J, Fischer M, Kassam Z (2018) Early antibiotic use after fecal microbiota transplantation increases risk of treatment failure. Clin Infect Dis 66:134–135

Wilson BC, Vatanen T, Cutfield WS, O’Sullivan JM (2019) The super-donor phenomenon in fecal microbiota transplantation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 9:2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00002

Anderson J, Edney R, Whelan K (2012) Systematic review: faecal microbiota transplantation in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 36:503–516

Angelberger S, Reinisch W, Makristathis A, Lichtenberger C, Dejaco C, Papay P, Novacek G, Trauner M, Loy A, Berry D (2013) Temporal bacterial community dynamics vary among ulcerative colitis patients after fecal microbiota transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol 108:1620–1630. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.257

Karussis D (2014) The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and the various related demyelinating syndromes: a critical review. J Autoimmun 48–49:134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.022

Heijtz RD, Wang S, Anuar F, Qian Y, Björkholm B, Samuelsson A, Hibberd ML, Forssberg H, Pettersson S (2011) Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:3047–3052

Rothhammer V, Mascanfroni ID, Bunse L, Takenaka MC, Kenison JE, Mayo L, Chao CC, Patel B, Yan R, Blain M, Alvarez JI, Kébir H, Anandasabapathy N, Izquierdo G, Jung S, Obholzer N, Pochet N, Clish CB, Prinz M, Prat A, Antel J, Quintana FJ (2016) Type I interferons and microbial metabolites of tryptophan modulate astrocyte activity and central nervous system inflammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat Med 22:586–597. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4106

Erny D, Hrabě de Angelis AL, Jaitin D, Wieghofer P, Staszewski O, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Mahlakoiv T, Jakobshagen K, Buch T, Schwierzeck V, Utermöhlen O, Chun E, Garrett WS, McCoy KD, Diefenbach A, Staeheli P, Stecher B, Amit I, Prinz M (2015) Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci 18:965–977. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4030

Margolis KG, Cryan JF, Mayer EA (2021) The microbiota-gut-brain axis: from motility to mood. Gastroenterology 160:1486–1501. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.066

Tremlett H, Fadrosh DW, Faruqi AA, Zhu F, Hart J, Roalstad S, Graves J, Lynch S, Waubant E (2016) Gut microbiota in early pediatric multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. Eur J Neurol 23:1308–1321. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.13026

Chen J, Chia N, Kalari KR, Yao JZ, Novotna M, Paz Soldan MM, Luckey DH, Marietta EV, Jeraldo PR, Chen X, Weinshenker BG, Rodriguez M, Kantarci OH, Nelson H, Murray JA, Mangalam AK (2016) Multiple sclerosis patients have a distinct gut microbiota compared to healthy controls. Sci Rep 6:28484. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28484

Miyauchi E, Shimokawa C, Steimle A, Desai MS, Ohno H (2022) The impact of the gut microbiome on extra-intestinal autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00727-y

Berer K, Gerdes LA, Cekanaviciute E, Jia X, Xiao L, Xia Z, Liu C, Klotz L, Stauffer U, Baranzini SE, Kümpfel T, Hohlfeld R, Krishnamoorthy G, Wekerle H (2017) Gut microbiota from multiple sclerosis patients enables spontaneous autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:10719–10724. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711233114