Abstract

Purpose of Review

The binding of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) to its primary receptor, scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SR-B1), is critical for lowering plasma cholesterol levels and reducing cardiovascular disease risk. This review provides novel insights into how the structural elements of SR-B1 drive efficient function with an emphasis on bidirectional cholesterol transport.

Recent Findings

We have generated a new homology model of full-length human SR-B1 based on the recent resolution of the partial structures of other class B scavenger receptors. Interrogating this model against previously published observations allows us to generate structurally informed hypotheses about SR-B1’s ability to mediate HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) transport. Furthermore, we provide a structural perspective as to why human variants of SR-B1 may result in impaired HDL-C clearance.

Summary

A comprehensive understanding of SR-B1’s structure–function relationships is critical to the development of therapeutic agents targeting SR-B1 and modulating cardiovascular disease risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SR-B1) is a membrane-spanning receptor highly expressed in the liver, gonads, and adrenal glands, with lower expression in macrophages, adipocytes, endothelial cells, and lung tissue (reviewed in [1]). As SR-B1 is predominantly expressed in tissues with high cholesterol demand, and more specifically, in glycolipid-rich caveolae and cholesterol-rich regions of the plasma membrane [2], it is unsurprising that SR-B1 is crucial for cholesterol metabolism. SR-B1 serves as the primary receptor for high-density lipoproteins (HDL) [3] and mediates bidirectional cholesterol transport between HDL and cells. Specifically, SR-B1 selectively delivers cholesteryl esters (CE) into cells from HDL, without holoparticle uptake of HDL [4, 5]. SR-B1 also effluxes free cholesterol (FC) out of cells into HDL [6]. Furthermore, the expression of SR-B1 re-distributes cholesterol within the plasma membrane by increasing cholesterol availability to the extracellular space [7, 8].

SR-B1’s most notable role is in the clearance of plasma cholesterol through the reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) pathway, where mature HDL particles deliver cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the liver for bodily excretion [9, 10]. Lipid-depleted HDL dissociates from SR-B1 and re-enters circulation to continue to participate in RCT. As such, efficient interaction between SR-B1 and HDL is required to maintain cholesterol homeostasis and protect against the plaque accumulation seen in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

The importance of SR-B1 in atheroprotection is well illustrated by in vivo studies. When SR-B1 is genetically deleted in wild-type mice, HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels are doubled and atherosclerotic plaques rapidly develop [11, 12]. SR-B1 deletion in atherosclerotic apoE knockout mice leads to myocardial infarction and early death [13]. Similarly, SR-B1 deletion in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor knockout mice fed a high-fat Western diet also exhibits early atherosclerosis [14, 15]. Alternatively, SR-B1 overexpression in wild-type mice results in decreased HDL-C levels [16,17,18,19] and less atherosclerotic plaque formation [20]. In addition, all nine identified human variants of SR-B1 result in elevated plasma HDL-C levels, with two variants (P376L- [21••] and G319V-SR-B1 [22••]) directly increasing the risk of ASCVD. Combining these clinical observations with mouse studies, SR-B1’s importance in maintaining appropriate HDL-C levels and mitigating ASCVD risk becomes increasingly clear.

In addition to its role in RCT, SR-B1 has been implicated in numerous biologic and pathologic processes including prevention of endotoxemia and sepsis [23, 24], T-cell maturation [25], LDL transcytosis in endothelial cells [26], platelet aggregation [27, 28], efferocytosis [29], endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activation and endothelial cell migration [30,31,32,33], female infertility [34], as well as the uptake of lipids (cholesteryl ester, free cholesterol, phospholipids, and triglycerides) [35] and fatty acids [36]. Moreover, increased expression of SR-B1 in patient tumors and cancer cell lines may be harnessed as a treatment target or disease biomarker (reviewed in [37]). SR-B1 has also been implicated in modulating diabetes risk [38,39,40]. As dyslipidemia, diabetes, and ASCVD are commonly comorbid conditions, understanding how SR-B1 modulates cholesterol homeostasis will help shed light on these prevalent conditions.

To fully comprehend the breadth of functions exerted by SR-B1, we must interrogate the structure of SR-B1 that underlies efficient receptor function. This review will summarize the currently known structural information about SR-B1 and identify gaps in our knowledge. The discussion will focus on how the structure of SR-B1 informs its functions, with an emphasis on cholesterol transport.

Homology Modeling of SR-B1

SR-B1 is a 509-amino acid transmembrane protein that belongs to the class B scavenger receptor family along with cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) and lysosomal integral membrane protein 2 (LIMP-2). All three class B scavenger receptors share a common structural blueprint: a large extracellular domain, two transmembrane domains, and short N- and C-terminal cytoplasmic tails. The lack of a high-resolution structure has forced investigators to rely on mutagenesis studies to identify structural elements of SR-B1 that drive its functions. Mutant SR-B1 receptors discussed in this review are summarized in Table 1.

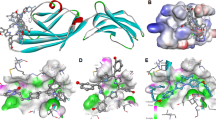

A major step forward in our understanding of class B scavenger receptor function was the resolution of the partial X-ray crystal structures of LIMP-2 [41•, 42,43,44] and CD36 [45•]. Additionally, Chadwick et al. utilized nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to solve the structure of residues 405–475 of SR-B1, which encompasses the C-terminal transmembrane domain and a flanking extracellular region [46••]. Due to the high levels of sequence similarity between class B scavenger receptors (~ 66% when comparing human SR-B1 to human CD36 or LIMP-2), we can use homology modeling to give structural context to SR-B1 mutagenesis studies. We have generated a model of full-length human SR-B1 (Fig. 1) using transform-restrained Rosetta (trRosetta) [47••], which incorporates deep learning and the solved structure of homologs CD36 [45•] and LIMP-2 [41•, 42,43,44] as templates for model generation. The newly launched Alphafold Protein Structure Database has also predicted the structure of full-length human SR-B1 [48•, 49•]. While similar to our trRosetta model, the Alphafold model predicts with very low confidence, a highly disordered C-terminal tail that dips back into the membrane. Our trRosetta model more reasonably predicts two short helices in the C-terminal region that are more compact and fully cytoplasmic. Others have generated SR-B1 homology models using alternative approaches [41•], but with the recent resolution of CD36’s structure and advances in homology modeling in the last 5 years, we are confident in using our in silico full-length model of SR-B1 to investigate how SR-B1’s structure influences function.

Homology model of human SR-B1. A homology model of full-length human SR-B1 was created using trRosetta and shows the three regions of SR-B1: a large extracellular domain, anchoring transmembrane domains, and N- and C- terminal cytoplasmic tails. A tri-helical bundle (purple) may bind SR-B1’s ligands. Non-polar residues (orange) and several other residues (cyan) within a predicted central β-sheet (navy blue) are important in cholesterol transport (see inset). Residue C384 (brown) has previously been predicted to lie at the entrance to a hydrophobic tunnel, but this hypothesis is not consistent with our model. The EAKL region (red) at the terminus of the C-terminal tail facilitates downstream signaling events. The leucine zipper motif (pink) within the C-terminal transmembrane domain and flanking extracellular region has been shown to facilitate oligomerization, while the GxxxG motif in the N-terminal transmembrane domain (green) has conflicting reports of its importance in oligomerization. Inset: an enlarged view of the central β-sheet, rotated 90° clockwise, to better view selected residues and their side chains. The homology model was generated from the partially solved structures of the luminal domain of human LIMP-2 (PDB: 4F7B, 5UPH, 4Q4B, 4Q4F), the extracellular domain of human CD36 (PDB: 5LGD), and murine SR-B1 residues 405–475 (PDB: 5KTF)

Extracellular Domain and Cholesterol Transport

The majority of SR-B1 structure–function studies focus on its extracellular domain, which binds various ligands, including HDL [3] (SR-B1’s primary ligand), apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) [50], apolipoprotein A-II [51], acetylated LDL, oxidized LDL [52], anionic lipids [53], serum amyloid A [54], and silica [55]. SR-B1 has also been shown to mediate viral entry of hepatitis C [56, 57] and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [58•] into cells. While SR-B1 binds to a variety of ligands, some ligands may share some common binding sites.

TMHMM, a transmembrane helix prediction program, predicts that the extracellular domain of human SR-B1 ranges from residues 36–439 (residues 32–439 for murine SR-B1) [59]. As shown in our homology model of full-length human SR-B1 (Fig. 1), two α-helical transmembrane domains anchor the extracellular domain, which consists of a central anti-parallel β-barrel and peripheral short α-helices. These interweaving secondary structures are connected by loops that likely confer conformational flexibility. The solved structure of residues 405–475 of SR-B1 [46••] aligns closely with this model, with the exception of residues 408–419 which lie within a β-strand in the homology model, but represent an α-helix in the NMR structure that may be a peptide artifact. Of note, our SR-B1 model suggests there is a tri-helical bundle at the apex, composed of residues A144-N150, M153-L166, and P186-Y194 (Fig. 1). Neculai et al. showed that mutations M159E and T165E within this helical bundle of human SR-B1 significantly reduced HDL binding compared to wild-type SR-B1 [41•]. An analogous three-helix bundle was identified as the main site of ligand binding in CD36 and LIMP-2 [41•, 42,43,44, 45•].

Previous hydropathy analyses revealed hydrophobic regions within the extracellular domain hypothesized to be important to SR-B1 function [60]. Non-polar residues within these regions (V67, L140, L142, V164, V221) of murine SR-B1 were mutated to disrupt hydrophobicity, and mutants displayed decreased HDL binding and bidirectional cholesterol transport. All residues are highly conserved with the exception of V164, which within human SR-B1 is a polar threonine that falls within the helical bundle of our model. Both V67 and V221 reside within β-strands and face the barrel center, while L140 sits below the tri-helical bundle, but still points toward the core (Fig. 1).

While the apical helices may mediate SR-B1 function, mutagenesis studies identified additional extracellular regions that mediate sophisticated coordination between many areas of SR-B1 and orient the receptor for efficient ligand binding and HDL-C transport. For example, several single amino acid substitutions (P412A [61], W415F [62], and G420A [63]) within the same β-strand (residues V409 to A421, Fig. 1) disrupt normal SR-B1 function. The side chains of both P412 and W415 protrude outwards from the β-barrel core (Fig. 1), making numerous contacts with other residues that when altered, could compromise protein stability and integrity. To better define extracellular regions important for function, short segments of SR-B1’s extracellular region were swapped with corresponding extracellular sequences of CD36 to form SR-B1/CD36 chimeras. Numerous chimeric receptors displayed defective HDL binding, selective uptake of HDL-CE and FC efflux [64], suggesting that multiple extracellular sub-regions of SR-B1 drive efficient cholesterol transport, instead of a single sub-region. Further investigation is required to untangle the mechanisms by which the extracellular region coordinates proper SR-B1 function.

While mutagenesis studies have shed light on structural regions key to SR-B1-mediated cholesterol transport, the exact pathway for the bidirectional movement of CE or FC between HDL and cells remains more elusive. There is a long-standing hypothesis that a hydrophobic channel shuttles cholesterol and other lipids between HDL and cells [35, 65]. This notion is supported by Neculai et al., who show a channel lining the extracellular domain of their SR-B1 homology model [41•]. The authors suggest that residue C384 sits within the lumen of their predicted channel, which is particularly interesting as C384 binds a small-molecule irreversible inhibitor of SR-B1, blocker of lipid transport-1 (BLT-1) [66]. BLT-1 disrupts SR-B1’s ability to mediate CE uptake, while simultaneously increasing SR-B1’s affinity for HDL. When C384 was mutated to a serine, BLT-1 inhibition was lost and cholesterol transport functions were restored [41•]. The predicted location of C384 within our model is not within a channel, but instead lies within a small extracellular pocket closer to the transmembrane region (Fig. 1) that may be responsible for lipid binding. Mechanisms and efficiency of lipid transport likely depend on the hydrophobicity of the lipid being transported and possibly, the properties of the HDL particle itself [35]. Our model shows a large hydrophobic pocket within the extracellular domain, but it is constricted at several regions and would be a difficult route for bulkier lipids. More realistically, upon ligand binding, SR-B1 may undergo conformational changes to form a hydrophobic tunnel to allow the efficient movement of lipids between HDL and cells, but further structural studies are required to resolve the precise mechanisms of lipid flux, and specifically, the bidirectional movement of cholesterol.

Transmembrane Domains and Oligomerization

TMHMM predicts that the N-terminal transmembrane domain (N-TMD) of human SR-B1 ranges from residues 13–35 (residues 9–31 in mouse), while the C-terminal transmembrane domain (C-TMD) of both human and mouse SR-B1 ranges from residues 440–462. As seen by our model in Fig. 1, the N- and C-terminal transmembrane helices extend into the extracellular space, to residues 43 and 422, respectively. As supported by the NMR structure of residues 405–475 of murine SR-B1 [46••] and consistent with TMHMM predictions, we display the C-TMD beginning at residue 440. The NMR structure of the C-TMD shows residue P438 near the transition into the extracellular region [46••] and it is possible this residue serves as a hinge to allow increased flexibility to this extracellular loop. Mutation of P438 results in ineffective bidirectional cholesterol transport [61], supporting its importance for normal SR-B1 function and conformation.

One major function of SR-B1’s transmembrane domains is in facilitating oligomer formation between SR-B1 monomers. The formation of SR-B1 dimers and higher order oligomers is well documented [67,68,69,70,71] and necessary for efficient function [46••, 70]; however, the actual dynamics of homo-oligomerization remain controversial. SR-B1 oligomeric complexes could form a large non-aqueous pore in the plasma membrane, providing an alternate or additional mechanism of lipid transport [35, 65]. Intermolecular disulfide bond formation may also play a role, as mutation of all extracellular cysteines in murine SR-B1 to serine allowed dimerization, but prevented the formation of higher order oligomers [72]. Both the N- and C-TMDs harbor glycine dimerization motifs (also known as GxxxG motifs) which promote the association of transmembrane helices [73]. The N-TMD glycine dimerization motif (G12-G15-G18-G25, Fig. 1) was shown to mediate dimerization [71]. Yet mutation of the C-TMD GxxxG motif did not impact SR-B1 self-association [63].

The C-TMD also contains a highly conserved leucine zipper motif, consisting of L413-L427-L434-L448-L455, that also extends into the extracellular region [46••] (Fig. 1). Murine SR-B1 also contains L441 within the leucine zipper motif. Mutagenesis was leveraged to create a leucine zipper-free receptor (∆LZ-SR-B1, where zipper leucines were mutated to alanine). ∆LZ-SR-B1’s inability to form higher order oligomers correlated with the inability to bind HDL, mediate HDL-CE uptake, and efflux FC [46••]. These observations were supported by earlier fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis showing that SR-B1 homo-dimerization occurs via C-TMD interactions alone [74]. Conversely, mutation of the N-TMD glycine dimerization motif (∆GDM-SR-B1 consisting of G15L-G18L-G25L) (Table 1) resulted in decreased oligomerization and HDL-CE selective uptake [71]. Most recently, Marques and Nyegaard et al. generated several mutant receptors to identify the source of SR-B1 oligomerization, including ∆GDM and L441A-L448A-L455A (the C-TMD residues of the leucine zipper) [70]. Microscopy studies showed ∆GDM-SR-B1 was able to oligomerize [70], contrary to previously published observations [71]. However, L441A-L448A-L455A SR-B1 displayed decreased HDL binding and CE uptake and formed fewer and smaller oligomers [70]. These studies support the idea that SR-B1 homo-oligomerization is driven by interactions between C-TMDs. This study also demonstrated that SR-B1 oligomerization is necessary for retention of a functional SR-B1 complex at the cell surface and that loss of oligomerization forces SR-B1 internalization and endocytosis.

Another unique role of SR-B1’s transmembrane domains is, in part, to modulate plasma membrane lipids. SR-B1 has the ability to redistribute membrane cholesterol pools and alter cellular cholesterol content [8]. Mutating numerous residues throughout SR-B1, including residues within the C-TMD, results in changes in cholesterol distribution [46••, 60,61,62, 64, 72, 75,76,77]. Furthermore, SR-B1 expression enriches the membrane in phospholipids that have longer and more unsaturated acyl tails [8, 75], supporting previous studies showing that SR-B1 knockout mice have thinner adrenal microvillar membranes [78]. While the precise mechanisms by which SR-B1 drives these lipid changes remain unclear, residue Q445 within the C-TMD was identified as a sensor of membrane cholesterol [79] that allows for downstream effects such as nitric oxide production and migration of endothelial cells [79, 80]. When Q445 was mutated to a non-reactive alanine, HDL binding and CE uptake were maintained, but mutant receptors displayed decreased membrane cholesterol interaction and eNOS activation [79]. While Q445 is important, there is more to uncover about how SR-B1 finely tunes cholesterol in cells and membranes and how cellular functions are impacted.

Cytoplasmic Tails and Intracellular Signaling

The N- and C-termini of SR-B1 reside within the cytoplasm. The human and mouse N-terminal tails (residues 1–12 and 1–8, respectively) are dispensable for cholesterol transport, as truncated SR-B1 lacking both native cytoplasmic domains retains HDL-C transport in cultured cells [81]. However, the longer C-terminal tail (residues 463–509 in humans and mice) which in our model is mostly unstructured except for two short alpha-helices has been implicated in signaling events that ultimately modulate nitric oxide production, apoptosis, and endothelial cell migration (reviewed in [82, 83]). Activation of eNOS relies on SR-B1’s EAKL sequence (residues 506–509, Fig. 1), a PDZK1-interacting domain within the C terminus [31, 80, 84, 85]. PDZK1 knockout mice display decreased hepatocyte SR-B1 surface expression and elevated plasma cholesterol levels [86]. Putative C-terminal tail interactions with PDZK1 and c-Src trigger PI3K and c-Src pathways to stimulate endothelial cell migration [33, 87]. The importance of the C-terminal tail is further demonstrated by studies of SR-B1.1, a splice variant of SR-B1, also referred to as SR-BII, that differs only in the C-terminal tail, which is shorter than SR-B1 by three residues and has a completely unique sequence [88]. Despite similar levels of HDL binding and CE transport between the splice variants [88], SR-B1.1 cannot activate eNOS [80], suggesting that only the SR-B1 C-terminal tail is critical for signaling. Additionally, the C-terminal residues 487–494 interact with dedicator of cytokinesis 4 (DOCK4) to mediate LDL transcytosis in endothelial cells [26]. Importantly, when the entire C-terminal tail is truncated in mice, hypercholesteremia and early death ensue [89].

Post-translational Modifications

The presence of intramolecular disulfide bonds likely maintains SR-B1 in a conformation that supports HDL-C transport. Our lab has reported that all six extracellular cysteine residues are involved in intramolecular disulfide bond formation [72], but others have shown that only two disulfide bonds form between C280/C334 and C321/C323, while C251 and C384 remain reduced [41•, 66, 90]. The latter is more consistent with our homology model, as C384 and C251 are on opposite faces of the extracellular domain and not within a distance compatible with disulfide bond formation. The existence of intermolecular disulfide bonds between SR-B1 monomers has not been reported.

Human and murine SR-B1 contain nine predicted N-linked glycosylation sites, with murine SR-B1 containing two additional sites [91]. Glycosylation, specifically at positions N108 and N173, is required for surface expression of SR-B1 [91]. Interestingly, two human variants of SR-B1, R174C and T175A, occur within the N173-X-T glycosylation sequence [76, 77, 92•]. In cultured cells, T175A displayed decreased surface expression due to loss of glycosylation [76], but R174C surface expression and glycosylation were not impacted [77]. Human mutations will be discussed in further detail below.

While extracellular post-translational modifications are important for ligand binding and expression, the role of fatty acylation at residues C462 and C470 in the intracellular C-terminus remains less clear. When these cysteines were mutated to serine to prevent acylation by fatty acids, HDL binding and bidirectional cholesterol transport were not altered [5, 88]. Further investigation is needed to determine if acylation increases membrane anchoring, lipophilicity, and stability of SR-B1 in the membrane. To our knowledge, the functions of other possible modifications, such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, sulfation, oxidation, or citrullination remain limited.

Human Relevance of SR-B1

Several polymorphisms of human SR-B1 have been identified in the human SCARB1 gene, including nine coding mutants: V32M, V111M, S112F, V135I, R174C, T175A, P297S, G319V, and P376L [21••, 22••, 76, 77, 92•, 93•, 94•]. The locations of these mutants are mapped to our homology model (Fig. 2) and share a common tale of discovery: patients were identified due to abnormally elevated plasma HDL-C and SCARB1 variants were identified by genomic sequencing. As described below, these human variants highlight the physiological importance of SR-B1 in reducing ASCVD risk by clearing HDL-C and lowering plasma cholesterol levels.

Predicted locations of human SR-B1 variants. A cropped view of the homology model shows the location of the nine coding variants of SR-B1 identified in human subjects to date (shown in pink). Mutations at V135, R174, and T175 cluster below the tri-helical region in the apex. Mutations at V111, S112, and G319 are exposed to the aqueous environment, while P297 and P376 lie closer to the plasma membrane and their mutation may disrupt interactions with neighboring residues or membrane lipids. V32M is uniquely located at the junction of the N-terminal transmembrane domain and the extracellular region. The side chains shown are for the native, non-mutated residue. The homology model was generated from the partially solved structures of the luminal domain of human LIMP-2 (PDB: 4F7B, 5UPH, 4Q4B, 4Q4F), the extracellular domain of human CD36 (PDB: 5LGD), and murine SR-B1 residues 405–475 (PDB: 5KTF)

All variants identified to date lie within the extracellular region of SR-B1 except for V32M, which sits at the junction between the N-TMD and extracellular region. V32M-SR-B1 was identified alongside V111M-, V135I-, and G319V-SR-B1 in a group of whole-genome sequenced Icelandic individuals with elevated plasma HDL-C levels. While none of these variants correlated with elevated ASCVD risk, they were associated with a significant decrease in gallstone formation [94•]. While not tested, it is possible that decreased bile production may be a result of impaired HDL-C delivery to the liver by these mutant receptors. Our homology model (Fig. 2) provides insight into the effects of these mutants. V135 falls below the apical tri-helical bundle and could affect ligand binding if the structure of the apex is disrupted. V111 is predicted to be solvent exposed within an extracellular β-strand near the N-TMD and may impact SR-B1 membrane dynamics. G319V is within a solvent-exposed loop in our model and in vitro studies showed that G319V-SR-B1 exhibited a decreased capacity to mediate HDL-CE uptake compared to wild-type SR-B1, despite comparable levels of cell surface expression [22••]. Information from G319V-SR-B1 cellular assays, combined with a recent clinical observation of recurrent myocardial infarctions in a young adult with the G319V-SR-B1 mutation [22••], highlights the delicate balance of cholesterol homeostasis maintained by SR-B1. The mechanisms by which the G319V variant is so damaging remain unclear. Koenig et al. utilized homology modeling to propose that G319 resides in an unspecified extracellular dimerization interface near the tri-helix apical bundle [22••]. They further suggest that the G319V mutation stabilizes dimers via hydrophobic interactions; however, assays to validate these claims were not presented.

Zanoni et al. identified a human subject homozygous for the P376L variant, as well as several P376L heterozygotes [21••]. While P376L-SR-B1 was associated with elevated HDL-C, no deviations from normal plasma LDL-cholesterol or triglyceride levels were observed. HDL particles from the P376L homozygote were increased in size, with elevated apoA-I and cholesterol content, but there was no difference in cholesterol efflux capacity compared to healthy controls. In vitro assays showed that compared to wild-type SR-B1, P376L-SR-B1 had decreased expression at the cell surface, as well as decreased HDL binding and HDL-CE selective uptake. Meta-analysis revealed P376L-SR-B1 carriers (both hetero- and homozygotes) were at an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease compared to non-carrier controls, making this the first human case to demonstrate that impaired HDL-C clearance via SR-B1 correlates with increased cardiovascular risk.

Mechanistically, Zanoni et al. suggested that mutation of P376 in SR-B1 disrupts post-translational N-linked glycosylation, even though this residue does not lie within an N-X-T glycosylation sequence. It is possible that the P376L mutation causes conformational changes that limit enzyme access to one of SR-B1’s glycosylation sites, preventing proper glycosylation and trafficking to the cell surface. This notion is partially supported by our homology model, which predicts P376 lies in a loop adjacent to the β-strand containing the glycosylated N383 (Fig. 2). Due to its proximity to the plasma membrane, P376L-SR-B1 may impact interactions with neighboring residues or the plasma membrane and disrupt SR-B1’s ability to effectively mediate cholesterol clearance. Proline residues are known to form “kinks” in secondary structures, as the backbone nitrogen is unable to form hydrogen bonds. Mutating a proline to a more electrostatically interactive leucine may alter flexibility or disrupt the secondary structure.

A similar proline disruption likely occurs with P297S-SR-B1, the first human variant of SR-B1 to be identified, in a family with several family members heterozygous for this mutation [93•]. Plasma HDL-CE was elevated in P297S-SR-B1 carriers, consistent with a decreased ability to clear HDL-C, which was demonstrated in mouse adenoviral studies. While P297S-SR-B1 carriers did not show an elevated risk of ASCVD, other functions of SR-B1 were disturbed. P297S carrier platelets displayed more aggregation and increased unesterified cholesterol content, while adrenal glands showed signs of insufficiency, namely, decreased urinary secretion of steroids. These phenotypes have not been studied with other SR-B1 variants. Correlating these observations to our homology model, P297 sits within a β-strand proximal to the transmembrane helices, with the proline side chain being exposed to the aqueous environment. As alluded to earlier, it is possible that mutating a kinked proline to a serine impacts structural integrity through the formation of additional hydrogen bonds.

S112F- and T175A-SR-B1 were identified in patients who had HDL-C levels above the 90th percentile; however, these patients did not display any signs of accelerated plaque formation or early ASCVD [92•]. While S112F-SR-B1 expresses at the cell surface at similar levels to wild-type SR-B1 in vitro, T175A-SR-B1 cell surface expression was diminished [76]. This is unsurprising, as T175A occurs within an N-X-T glycosylation sequence and glycosylation of SR-B1 at position 173 is critical for receptor trafficking to the cell surface [91]. Both S112F- and T175A-SR-B1 also display reduced binding to hepatitis C, decreasing viral entry into hepatocytes [95], suggesting that these mutations directly affect ligand binding sites. S112 is located in the same β-strand as V111, near the membrane (Fig. 2), while T175A is located near the apex. Both S112F and T175A-SR-B1 involve the mutation of polar residues into hydrophobic residues. This change likely disrupts interactions with surrounding residues, which would corroborate the in vitro disruptions to SR-B1 function.

An individual heterozygous for R174C-SR-B1 is the most recent human variant of SR-B1 characterized to date [77]. R174 is adjacent to T175, in the center of the N-X-T glycosylation sequence and is partially solvent-exposed near the apex (Fig. 2). Unlike T175A-SR-B1, R174C-SR-B1 exhibits normal levels of expression, but in vitro assays illustrate that R174C-SR-B1 displays decreased HDL binding, HDL-CE uptake, and FC efflux [77]. Despite these disruptions, R174C-SR-B1 still forms dimers and higher order oligomers and is not directly associated with an elevated risk of ASCVD. May et al. suggest that impaired function is due to reducing the cationic surface charge of the apex [77]. Differing reports of how various SR-B1 mutations impact ASCVD risk leaves the following questions: Why do some human mutations have no direct effect on atherosclerosis while others exhibit severe clinical phenotypes? How can we correlate these differences to alterations in SR-B1’s structure?

Therapeutic Potential of SR-B1 and Future Considerations

SR-B1 has been considered a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of ASCVD given its importance in mediating HDL-C clearance. However, broadly activating whole-body SR-B1 activity may be an oversimplistic approach that does not account for the nuances in SR-B1 function. For example, SR-B1 mediates LDL transcytosis across endothelial cells, a process that could contribute to atherogenesis [26]. Furthermore, SR-B1 expression in various cancers increases proliferation and tumor growth [96]. As such, applying a structure-guided approach to the design of small-molecule inhibitors or activators is necessary as we continue to learn more about the tissue- and ligand-specific effects of SR-B1 in various diseases. A promising approach is to clinically target tissue-specific expression through lipoprotein-like nanoparticles to deliver insoluble compounds via SR-B1 or other receptors (reviewed in [97]).

As an integral membrane protein, the impact of the plasma membrane on SR-B1 function must be considered. SR-B1’s localization and clustering in sphingolipid-rich microdomains [2] and ability to interact with itself or other proteins likely impacts receptor function. For example, the extracellular matrix protein procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer protein 2 (PCPE2) has recently been shown to enhance SR-B1’s cholesterol transport functions in hepatocytes [98] and adipocytes [99]. SR-B1 has been reported to serve as a co-factor to facilitate SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells [58•]. PDZ1 domain-containing proteins Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor (NHERF1) and GAIP-interacting protein, C terminus 1 (GIPC) modulate SR-B1 activity through interaction with the C-TMD [100, 101]. Future investigations must focus on the intricacies of SR-B1 interaction with membrane lipids and proteins and determine how these relationships impact SR-B1’s ability to enhance cholesterol transport.

Conclusion

In lieu of a full-length structure, our homology model is a helpful tool to contextualize in vitro data. However, viewing SR-B1 as a static molecule goes against the fluidity of structural biology and scavenger receptor biology. SR-B1’s unique folding patterns and sequence allow it to bind a variety of ligands, mediate differential effects in response to each ligand, and sense membrane cholesterol. To exert such a breadth of functions, SR-B1’s structure must be flexible and dynamic, facilitating appropriate conformational changes and downstream effects in response to the binding of various ligands. In vitro studies demonstrate that residues in many different regions collaborate to support SR-B1’s functions, while human variants of SR-B1 are a reminder that subtle changes to structure can have adverse effects on cholesterol levels and cardiovascular health. Decoding the subtle mechanisms of this multifaceted scavenger receptor, in the presence and absence of a variety of ligands and membrane lipids, is achievable with modern advances in structural determination and imaging. Further explorations of the SR-B1 structure–function axis will yield promising discoveries that change the way we lower plasma cholesterol and treat ASCVD.

Abbreviations

- apoA-I:

-

Apolipoprotein A-I

- ASCVD:

-

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- BLT-1:

-

Blocker of lipid transport 1

- CD36:

-

Cluster of differentiation 36

- CE:

-

Cholesteryl ester

- DOCK4:

-

Dedicator of cytokinesis 4

- eNOS:

-

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- FC:

-

Free cholesterol

- GIPC1:

-

GAIP-interacting protein, C terminus 1

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-CE:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesteryl ester

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- LIMP-2:

-

Lysosomal integral membrane protein 2

- NHERF:

-

Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor

- NMR:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- PCPE2:

-

Procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer protein 2

- PDZ:

-

PSD95, D1g, and ZO1

- PDZK1:

-

PDZ containing protein 1

- RCT:

-

Reverse cholesterol transport

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SR-B1:

-

Scavenger receptor class B type I

- SR-B1.1:

-

Alternatively spliced scavenger receptor class B type I

- TMD:

-

Transmembrane domain

- trRosetta:

-

Transform-restrained Rosetta

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Hoekstra M. SR-BI as target in atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease - a comprehensive appraisal of the cellular functions of SR-BI in physiology and disease. Atherosclerosis. 2017;258:153–61.

Babitt J, Trigatti B, Rigotti A, Smart EJ, Anderson RGW, Xu S, Krieger M. Murine SR-BI, a high density lipoprotein receptor that mediates selective lipid uptake, is N-glycosylated and fatty acylated and colocalizes with plasma membrane caveolae. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13242–9.

Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, Xu S, Hobbs HH, Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science. 1996;271:518–20.

Brundert M, Ewert A, Heeren J, Behrendt B, Ramakrishnan R, Greten H, Merkel M, Rinninger F. Scavenger receptor class B type I mediates the selective uptake of high-density lipoprotein-associated cholesteryl ester by the liver in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:143–8.

Gu X, Trigatti B, Xu S, Acton S, Babitt J, Krieger M. The efficient cellular uptake of high density lipoprotein lipids via scavenger receptor class B type I requires not only receptor- mediated surface binding but also receptor-specific lipid transfer mediated by its extracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:35388.

Gu X, Kozarsky K, Krieger M. Scavenger receptor class B, type I-mediated [3H]cholesterol efflux to high and low density lipoproteins is dependent on lipoprotein binding to the receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29993–30001.

De La Llera-Moya M, Rothblat GH, Connelly MA, Kellner-Weibel G, Sakr SW, Phillips MC, Williams DL. Scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) mediates free cholesterol flux independently of HDL tethering to the cell surface. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:575–80.

Kellner-Weibel G, De La Llera-Moya M, Connelly MA, Stoudt G, Christian AE, Haynes MP, Williams DL, Rothblat GH. Expression of scavenger receptor BI in COS-7 cells alters cholesterol content and distribution. Biochemistry. 2000;39:221–9.

Out R, Hoekstra M, Spijkers JAA, Kruijt JK, Van Eck M, Bos IST, Twisk J, Van Berkel TJC. Scavenger receptor class B type I is solely responsible for the selective uptake of cholesteryl esters from HDL by the liver and the adrenals in mice. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:2088–95.

Ji Y, Wang N, Ramakrishnan R, Sehayek E, Huszar D, Breslow JL, Tall AR. Hepatic scavenger receptor BI promotes rapid clearance of high density lipoprotein free cholesterol and its transport into bile. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33398–402.

Varban ML, Rinninger F, Wang N, et al. Targeted mutation reveals a central role for SR-BI in hepatic selective uptake of high density lipoprotein cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4619–24.

Rigotti A, Trigatti BL, Penman M, Rayburn H, Herz J, Krieger M. A targeted mutation in the murine gene encoding the high density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor scavenger receptor class B type I reveals its key role in HDL metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12610–5.

Braun A, Trigatti BL, Post MJ, Sato K, Simons M, Edelberg JM, Rosenberg RD, Schrenzel M, Krieger M. Loss of SR-BI expression leads to the early onset of occlusive atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, spontaneous myocardial infarctions, severe cardiac dysfunction, and premature death in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2002;90:270–6.

Covey SD, Krieger M, Wang W, Penman M, Trigatti BL. Scavenger receptor class B type I-mediated protection against atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-negative mice involves its expression in bone marrow-derived cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1589–94.

Huszar D, Varban ML, Rinninger F, Feeley R, Arai T, Fairchild-Huntress V, Donovan MJ, Tall AR. Increased LDL cholesterol and atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice with attenuated expression of scavenger receptor B1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1068–73.

Wang N, Arai T, Ji Y, Rinninger F, Tall AR. Liver-specific overexpression of scavenger receptor BI decreases levels of very low density lipoprotein ApoB, low density lipoprotein ApoB, and high density lipoprotein in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32920–6.

Ueda Y, Royer L, Gong E, Zhang J, Cooper PN, Francone O, Rubin EM. Lower plasma levels and accelerated clearance of high density lipoprotein (HDL) and non-HDL cholesterol in scavenger receptor class B type I transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7165–71.

Webb NR, De Beer MC, Yu J, Kindy MS, Daugherty A, Van Der Westhuyzen DR, De Beer FC. Overexpression of SR-BI by adenoviral vector promotes clearance of apoA-I, but not apoB, in human apoB transgenic mice. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1421–8.

Kozarsky KF, Donahee MH, Rigotti A, Iqbal SN, Edelman ER, Krieger M. Overexpression of the HDL receptor SR-BI alters plasma HDL and bile cholesterol levels. Nature. 1997;387:414–7.

Kozarsky KF, Donahee MH, Glick JM, Krieger M, Rader DJ. Gene transfer and hepatic overexpression of the HDL receptor SR-BI reduces atherosclerosis in the cholesterol-fed LDL receptor-deficient mouse. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:721–7.

•• Zanoni P, Khetarpal SA, Larach DB, et al (2016) Rare variant in scavenger receptor BI raises HDL cholesterol and increases risk of coronary heart disease. Science 351:1166–1171. This groundbreaking paper was the first to identify a human mutation in SR-BI that associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

•• Koenig SN, Sucharski HC, Jose EM, et al (2021) Inherited variants in SCARB1 cause severe early-onset coronary artery disease. Circ Res 129:296–307. This study draws a direct association between mutations in SCARB1 to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and myocardial infarction

Cai L, Ji A, De Beer FC, Tannock LR, Van Der Westhuyzen DR. SR-BI protects against endotoxemia in mice through its roles in glucocorticoid production and hepatic clearance. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:364–75.

Guo L, Song Z, Li M, Wu Q, Wang D, Feng H, Bernard P, Daugherty A, Huang B, Li XA. Scavenger receptor BI protects against septic death through its role in modulating inflammatory response. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19826–34.

Zheng Z, Ai J, Guo L, Ye X, Bondada S, Howatt D, Daugherty A, Li X. SR-BI (scavenger receptor class B type 1) Is critical in maintaining normal T-cell development and enhancing thymic regeneration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:2706–17.

Huang L, Chambliss KL, Gao X, et al. SR-B1 drives endothelial cell LDL transcytosis via DOCK4 to promote atherosclerosis. Nature. 2019;569:565–9.

Dole VS, Matuskova J, Vasile E, Yesilaltay A, Bergmeier W, Bernimoulin M, Wagner DD, Krieger M. Thrombocytopenia and platelet abnormalities in high-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1111–6.

Imachi H, Murao K, Cao W, Tada S, Taminato T, Wong NCW, Takahara J, Ishida T. Expression of human scavenger receptor B1 on and in human platelets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:898–904.

Tao H, Yancey PG, Babaev VR, Blakemore JL, Zhang Y, Ding L, Fazio S, Linton MF. Macrophage SR-BI mediates efferocytosis via Src/PI3K/Rac1 signaling and reduces atherosclerotic lesion necrosis. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:1449–60.

Yuhanna IS, Zhu Y, Cox BE, et al. High-density lipoprotein binding to scavenger receptor-BI activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat Med. 2001;7:853–7.

Mineo C, Yuhanna IS, Quon MJ, Shaul PW. High density lipoprotein-induced endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activation is mediated by Akt and MAP kinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9142–9.

Nofer JR, Van Der Giet M, Tölle M, et al. HDL induces NO-dependent vasorelaxation via the lysophospholipid receptor S1P3. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:569–81.

Seetharam D, Mineo C, Gormley AK, et al. High-density lipoprotein promotes endothelial cell migration and reendothelialization via scavenger receptor-B type I. Circ Res. 2006;98:63–72.

Miettinen HE, Rayburn H, Krieger M. Abnormal lipoprotein metabolism and reversible female infertility in HDL receptor (SR-BI)-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1717–22.

Thuahnai ST, Lund-Katz S, Williams DL, Phillips MC. Scavenger receptor class B, type I-mediated uptake of various lipids into cells: influence of the nature of the donor particle interaction with the receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43801–8.

Wang W, Yan Z, Hu J, Shen W-J, Azhar S, Kraemer FB. Scavenger receptor class B, type 1 facilitates cellular fatty acid uptake. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2020;1865:158554.

Rajora MA, Zheng G. Targeting SR-BI for cancer diagnostics, imaging and therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:1–8.

Murao K, Yu X, Imachi H, Cao WM, Chen K, Matsumoto K, Nishiuchi T, Wong NCW, Ishida T. Hyperglycemia suppresses hepatic scavenger receptor class B type I expression. Am J Physiol - Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:78–87.

McCarthy JJ, Somji A, Weiss LA, Steffy B, Vega R, Barrett-Connor E, Talavera G, Glynne R. Polymorphisms of the scavenger receptor class B member 1 are associated with insulin resistance with evidence of gene by sex interaction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1789–96.

Rein-Fischboeck L, Krautbauer S, Eisinger K, Pohl R, Meier EM, Weiss TS, Buechler C. Hepatic scavenger receptor BI is associated with type 2 diabetes but unrelated to human and murine non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;467:377–82.

• Neculai D, Schwake M, Ravichandran M, et al (2013) Structure of LIMP-2 provides functional insights with implications for SR-BI and CD36. Nature 504:172–176. The extracellular structure of LIMP-2 was the first class B scavenger to be resolved and laid the foundation for current structural studies and homology model generation.

Conrad KS, Cheng TW, Ysselstein D, et al. Lysosomal integral membrane protein-2 as a phospholipid receptor revealed by biophysical and cellular studies. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1908.

Dang M, Wang X, Wang Q, et al. Molecular mechanism of SCARB2-mediated attachment and uncoating of EV71. Protein Cell. 2014;5:692–703.

Zhao Y, Ren J, Padilla-Parra S, Fry EE, Stuart DI. Lysosome sorting of β-glucocerebrosidase by LIMP-2 is targeted by the mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4321.

• Hsieh FL, Turner L, Bolla JR, Robinson C V., Lavstsen T, Higgins MK (2016) The structural basis for CD36 binding by the malaria parasite. Nat Commun 7:12837. This study describes the high-resolution structure of the extracellular region of CD36, adding to our knowledge of structures of class B scavenger receptors and their structure-function relationships.

•• Chadwick AC, Jensen DR, Hanson PJ, Lange PT, Proudfoot SC, Peterson FC, Volkman BF, Sahoo D (2017) NMR structure of the C-terminal transmembrane domain of the HDL receptor, SR-BI, and a functionally relevant leucine zipper motif. Structure 25:446–457. This study describes the NMR structure of an SR-BI peptide containing the C-terminal transmembrane domain and a flanking extracellular region. This is the first and only SR-BI structural information to date.

•• Yang J, Anishchenko I, Park H, Peng Z, Ovchinnikov S, Baker D (2020) Improved protein structure prediction using predicted interresidue orientations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:1496–1503. Recent advances in protein modeling and structural prediction software have allowed for the generation of remarkably accurate models that allow for analysis of proteins in lieu of a experimentally-resolved structure.

• Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, et al (2021) Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596:583–589. The recently released, but long anticipated Alphafold provides an additional method of in silco protein structure prediction.

• Tunyasuvunakool K, Adler J, Wu Z, et al (2021) Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome. Nature 596:590–596. Structures of every protein in the human genome have been predicted using Alphafold and made publically available via a web database.

Liadaki KN, Liu T, Xu S, Ishida BY, Duchateaux PN, Krieger JP, Kane J, Krieger M, Zannis VI. Binding of high density lipoprotein (HDL) and discoidal reconstituted HDL to the HDL receptor scavenger receptor class B type I: effect of lipid association and ApoA-I mutations on receptor binding. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21262–71.

De Beer MC, Durbin DM, Cai L, Mirocha N, Jonas A, Webb NR, De Beer FC, Van der Westhuyzen DR. Apolipoprotein A-II modulates the binding and selective lipid uptake of reconstituted high density lipoprotein by scavenger receptor BI. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15832–9.

Calvo D, Gomez-Coronado D, Lasunción MA, Vega MA (1997) CLA-1 Is an 85-kD plasma membrane glycoprotein that acts as a high-affinity receptor for both native (HDL, LDL, and VLDL) and modified (OxLDL and AcLDL) lipoproteins. 2341–2349

Rigotti A, Acton SL, Krieger M. The class B scavenger receptors SR-BI and CD36 are receptors for anionic phospholipids. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16221–4.

Cai L, De Beer MC, De Beer FC, Van Der Westhuyzen DR. Serum amyloid a is a ligand for scavenger receptor class B type I and inhibits high density lipoprotein binding and selective lipid uptake. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2954–61.

Tsugita M, Morimoto N, Tashiro M, Kinoshita K, Nakayama M. SR-B1 Is a silica receptor that mediates canonical inflammasome activation. Cell Rep. 2017;18:1298–311.

Scarselli E, Ansuini H, Cerino R, Roccasecca RM, Acali S, Filocamo G, Traboni C, Nicosia A, Cortese R, Vitelli A. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 2002;21:5017–25.

Bartosch B, Vitelli A, Granier C, Goujon C, Dubuisson J, Pascale S, Scarselli E, Cortese R, Nicosia A, Cosset FL. Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41624–30.

• Wei C, Wan L, Yan Q, et al (2020) HDL-scavenger receptor B type 1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 entry. Nat Metab 2:1391–1400. SR-BI is implicated in the viral entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells and illustrates the diverse range of ligands and functions of SR-BI in different cell and tissue types.

Krogh A, Larsson B, Von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–80.

Papale GA, Nicholson K, Hanson PJ, Pavlovic M, Drover VA, Sahoo D. Extracellular hydrophobic regions in scavenger receptor BI play a key role in mediating HDL-cholesterol transport. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;496:132–9.

Proudfoot SC, Sahoo D. Proline residues in scavenger receptor-BI’s C-terminal region support efficient cholesterol transport. Biochem J. 2019;476:951–63.

Holme RL, Miller JJ, Nicholson K, Sahoo D. Tryptophan 415 is critical for the cholesterol transport functions of scavenger receptor BI. Biochemistry. 2016;131:1796–803.

Parathath S, Sahoo D, Darlington YF, Peng Y, Collins HL, Rothblat GH, Williams DL, Connelly MA. Glycine 420 near the C-terminal transmembrane domain of SR-BI is critical for proper delivery and metabolism of high density lipoprotein cholesteryl ester. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24976–85.

Kartz GA, Holme RL, Nicholson K, Sahoo D. SR-BI/CD36 chimeric receptors define extracellular subdomains of SR-BI critical for cholesterol transport. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6173–82.

Rodrigueza WV, Thuahnai ST, Temel RE, Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC, Williams DL. Mechanism of scavenger receptor class B type I-mediated selective uptake of cholesteryl esters from high density lipoprotein to adrenal cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20344–50.

Yu M, Romer KA, Nieland TJF, Xu S, Saenz-Vash V, Penman M, Yesilaltay A, Carr SA, Krieger M. Exoplasmic cysteine Cys384 of the HDL receptor SR-BI is critical for its sensitivity to a small-molecule inhibitor and normal lipid transport activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12243–8.

Reaven E, Cortez Y, Leers-Sucheta S, Nomoto A, Azhar S. Dimerization of the scavenger receptor class B type I: formation, function, and localization in diverse cells and tissues. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:513–28.

Sahoo D, Darlington YF, Pop D, Williams DL, Connelly MA. Scavenger receptor class B Type I (SR-BI) assembles into detergent-sensitive dimers and tetramers. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2007;1771:807–17.

Chadwick AC, Jensen DR, Peterson FC, Volkman BF, Sahoo D. Expression, purification and reconstitution of the C-terminal transmembrane domain of scavenger receptor BI into detergent micelles for NMR analysis. Protein Expr Purif. 2015;107:35–42.

Marques PE, Nyegaard S, Collins RF, Troise F, Freeman SA, Trimble WS, Grinstein S. Multimerization and retention of the scavenger receptor SR-B1 in the plasma membrane. Dev Cell. 2019;50:1–13.

Gaidukov L, Nager AR, Xu S, Penman M, Krieger M. Glycine dimerization motif in the N-terminal transmembrane domain of the high density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI required for normal receptor oligomerization and lipid transport. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18452–64.

Papale GA, Hanson PJ, Sahoo D. Extracellular disulfide bonds support scavenger receptor class B type I-mediated cholesterol transport. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6245–54.

Russ WP, Engelman DM. The GxxxG motif: A framework for transmembrane helix-helix association. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:911–9.

Sahoo D, Peng Y, Smith J, Darlington Y. Scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI) homo-dimerizes via its C-terminal region: fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:818–29.

Parathath S, Connelly MA, Rieger RA, Klein SM, Abumrad NA, De La Llera-Moya M, Iden CR, Rothblat GH, Williams DL. Changes in plasma membrane properties and phosphatidylcholine subspecies of insect Sf9 cells due to expression of scavenger receptor class B, type I, and CD36. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41310–8.

Chadwick AC, Sahoo D. Functional characterization of newly-discovered mutations in human SR-BI. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45660.

May SC, Dron JS, Hegele RA, Sahoo D. Human variant of scavenger receptor BI (R174C) exhibits impaired cholesterol transport functions. J Lipid Res. 2021;62:100045.

Williams DL, Wong JS, Hamilton RL. SR-BI is required for microvillar channel formation and the localization of HDL particles to the surface of adrenocortical cells in vivo. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:544–9.

Saddar S, Carriere V, Lee W-R, et al. Scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) is a -plasma membrane cholesterol sensor. Circ Res. 2013;112:140–51.

Assanasen C, Mineo C, Seetharam D, Yuhanna IS, Marcel YL, Connelly MA, Williams DL, De La Llera-Moya M, Shaul PW, Silver DL. Cholesterol binding, efflux, and a PDZ-interacting domain of scavenger receptor-BI mediate HDL-initiated signaling. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:969–77.

Connelly MA, De la Llera-Moya M, Monzo P, Yancey PG, Drazul D, Stoudt G, Fournier N, Klein SM, Rothblat GH, Williams DL. Analysis of chimeric receptors shows that multiple distinct functional activities of scavenger receptor, class B, type I (SR-BI), are localized to the extracellular receptor domain. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5249–59.

Al-Jarallah A, Trigatti BL. A role for the scavenger receptor, class B type I in high density lipoprotein dependent activation of cellular signaling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2010;1801:1239–48.

Saddar S, Mineo C, Shaul PW. Signaling by the high-affinity HDL receptor scavenger receptor B type i. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:144–50.

Silver DL. A carboxyl-terminal PDZ-interacting domain of scavenger receptor B, type I is essential for cell surface expression in liver. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34042–7.

Kocher O, Birrane G, Tsukamoto K, Fenske S, Yesilaltay A, Pal R, Daniels K, Ladias JAA, Krieger M. In vitro and in vivo analysis of the binding of the C terminus of the HDL receptor scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI), to the PDZ1 domain of its adaptor protein PDZK1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34999–5010.

Kocher O, Yesilaltay A, Cirovic C, Pal R, Rigotti A, Krieger M. Targeted disruption of the PDZK1 gene in mice causes tissue-specific depletion of the high density lipoprotein receptor scavenger receptor class B type I and altered lipoprotein metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52820–5.

Zhu W, Saddar S, Seetharam D, Chambliss KL, Longoria C, Silver DL, Yuhanna IS, Shaul PW, Mineo C. The scavenger receptor class B type I adaptor protein PDZK1 maintains endothelial monolayer integrity. Circ Res. 2008;102:480–7.

Webb NR, Connell PM, Graf GA, Smart EJ, De Villiers WJS, De Beer FC, Van Der Westhuyzen DR. SR-BII, an isoform of the scavenger receptor BI containing an alternate cytoplasmic tail, mediates lipid transfer between high density lipoprotein and cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15241–8.

Pal R, Ke Q, Pihan GA, Yesilaltay A, Penman ML, Wang L, Chitraju C, Kang PM, Krieger M, Kocher O. Carboxy-terminal deletion of the HDL receptor reduces receptor levels in liver and steroidogenic tissues, induces hypercholesterolemia, and causes fatal heart disease. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol. 2016;311:H1392–408.

Yu M, Lau TY, Carr SA, Krieger M. Contributions of a disulfide bond and a reduced cysteine side chain to the intrinsic activity of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI. Biochemistry. 2012;51:10044–55.

Viñals M, Xu S, Vasile E, Krieger M. Identification of the N-linked glycosylation sites on the high density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor SR-BI and assessment of their effects on HDL binding and selective lipid uptake. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5325–32.

• Brunham L, Tietjen I, Bochem A, et al (2011) Novel mutations in scavenger receptor BI associated with high HDL cholesterol in humans. Clin Genet 79:575–581. Two mutations of SR-BI, S112F and T175A, were reported in patients with elevated plasma HDL-cholesterol.

• Vergeer M, Korporaal S, Franssen R, et al (2011) Genetic variant of the scavenger receptor BI in humans. N Engl J Med 364:136–45. The first human variant of SR-BI was reported in patients with abnormally high plasma HDL-C.

• Helgadottir A, Sulem P, Thorgeirsson G, et al (2018) Rare SCARB1 mutations associate with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol but not with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 39:2172–2178. Four coding variants of SR-BI were identified in an Icelandic population and associated with elevated HDL-C, but the studies noted no increase in cardiovascular disease risk.

Westhaus S, Deest M, Nguyen ATX, et al. Scavenger receptor class B member 1 (SCARB1) variants modulate hepatitis C virus replication cycle and viral load. J Hepatol. 2017;67:237–45.

Gutierrez-Pajares JL, Ben HC, Chevalier S, Frank PG. SR-BI: Linking cholesterol and lipoprotein metabolism with breast and prostate cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:1–9.

Mulder WJM, Van Leent MMT, Lameijer M, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA, Pérez-Medina C. High-density lipoprotein nanobiologics for precision medicine. Acc Chem Res. 2018;51:127–37.

Pollard RD, Blesso CN, Zabalawi M, et al. Procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer protein 2 (PCPE2) reduces atherosclerosis in mice by enhancing scavenger receptor class B1 (SR-BI)-mediated high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesteryl ester uptake. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:15496–511.

Xu H, Thomas MJ, Kaul S, et al. Pcpe2, a novel extracellular matrix protein, regulates adipocyte SR-BI–mediated high-density lipoprotein uptake. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:2708–25.

Hu Z, Hu J, Zhang Z, Shen WJ, Yun CC, Berlot CH, Kraemer FB, Azhar S. Regulation of expression and function of scavenger receptor class B, type i (SR-BI) by Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factors (NHERFs). J Biol Chem. 2013;288:11416–35.

Zhang Z, Zhou Q, Liu R, Liu L, Shen WJ, Azhar S, Qu YF, Guo Z, Hu Z. The adaptor protein GIPC1 stabilizes the scavenger receptor SR-B1 and increases its cholesterol uptake. J Biol Chem. 2021;296:100616.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Sarah May, Kay Nicholson, Darcy Knaack, and Gage Stuttgen for the helpful editing of this review.

Funding

This work was financially supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL58012 (D.S.), HL138907 (D.S.), AI147500 (D.S.), and HL151048 (H.R.P.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Vascular Biology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Powers, H.R., Sahoo, D. SR-B1’s Next Top Model: Structural Perspectives on the Functions of the HDL Receptor. Curr Atheroscler Rep 24, 277–288 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-022-01001-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-022-01001-1