Abstract

Background

Smell and taste dysfunctions (STDs) are symptoms associated with COVID-19 syndrome, even if their incidence is still uncertain and variable.

Aims

In this study, the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on chemosensory function have been investigated using both a self-reporting questionnaire on smell and flavor perception, and a simplified flavor test.

Methods

A total of 111 subjects (19 hospitalized [HOS] and 37 home-isolated [HI] COVID-19 patients, and 55 healthy controls [CTRL]) were enrolled in the study. They received a self-evaluation questionnaire and a self-administered flavor test kit. The flavor test used consists in the self-administration of four solutions with a pure olfactory stimulus (coffee), a mixed olfactory-trigeminal stimulus (peppermint), and a complex chemical mixture (banana).

Results

After SARS-CoV-2 infection, HOS and HI patients reported similar prevalence of STDs, with a significant reduction of both smell and flavor self-estimated perception. The aromas of the flavor test were recognized by HI and HOS COVID-19 patients similarly to CTRL; however, the intensity of the perceived aromas was significantly lower in patients compared to controls.

Conclusion

Data reported here suggests that a chemosensory impairment is present after SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the modified “flavor test” could be a novel self-administering objective screening test to assess STDs in COVID-19 patients.

Clinical trial registration no. NCT04840966; April 12, 2021, retrospectively registered

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In December 2019 a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was first reported in China. The rapid spread of the virus and its substantial morbidity and mortality has prompted the World Health Organization to declare the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic [1].

Clinical manifestations of the infection range from mild to critical, even if the most serious effect of COVID-19 infection is interstitial pneumonia [2]. It is well known that viruses responsible for the common cold can cause post-viral smell impairment. Post-viral hypo/anosmia is one of the leading causes of smell deficiencies in adults [3]. However, while fever and cough are common symptoms of several viral infections, recent research indicated that sudden smell and taste dysfunctions (STDs) are cardinal, early, and potentially specific symptoms of COVID-19, also in otherwise asymptomatic individuals [4,5,6]. For instance, many scientific societies have published guidelines including STDs among the diagnostic criteria of COVID-19 [7, 8]. A possible reason for the olfactory impairment in COVID-19 patients is the high expression in nasal epithelial and olfactory cells of ACE2, the target protein used by SARS-CoV-2 to infect the host cells [9,10,11,12]. Olfactory dysfunction can be either conductive, mainly due to the physical blockage of odors in reaching the olfactory neuroepithelium, or sensorineural, due to the interruption of the route from olfactory receptors to the brain cortex, mainly caused by viral infections, head injuries, or neurodegenerative diseases. Previous studies proposed a propagation mechanism of SARS-CoV2, as well as other SARS-CoV infections, across the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, i.e., from the nose to the olfactory neuroepithelium, where ACE2 receptors are highly expressed. This viral neurotropism through the olfactory bulb is thought to be especially responsible for the post-COVID anosmia [12, 13].

The real incidence of STDs in COVID-19 patients is still uncertain and variable. Most of the published studies evaluated the presence of STDs using only questionnaire or phone/mail interviews, whereas only a few studies have used a direct evaluation with validated methods [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The use of specific chemosensory tests to evaluate STDs, although desirable, can imply several limitations. These include unnecessary time of physician’s exposure to virus, discomfort for patients (often in compromised general conditions), and high costs, also considering that the tests must be single-patient and non-reusable [14].

To better understand the COVID-related STDs, it is crucial to point out that most patients report a reduced/discontinued or distorted ability to taste flavors [22]. Flavor is determined by the unified perceptual experience or “gestalt” of a food that arises from the integration of sense of smell with several peripherally distinct sensory inputs, including taste, texture, viscosity, temperature, sight, and even the sound of foods or oral nociception (pain) [23, 24]. For instance, smell can arise from an external or internal source, this latter from inside the mouth during food consumption. Blankenship et al. demonstrated that internal odors share processing circuitry with taste and rapidly induce flavor preferences [25]. So, retro-nasal olfaction is probably the main determinant of flavor detection [26, 27]. Of particular interest is a recent study reporting that the 67% of COVID-19 patients experienced alterations in the retro-nasal smell; indeed, 42% reported a complete loss of retro-nasal smell perception, 35% reported that food had a different flavor than usual, and 17% reported a decreased retro-nasal smell perception. Moreover, 6% reported smell-specific perception, meaning some smell were perceived retro-nasally, while others were not [28].

Recently, our group has developed and validated a chemosensory test (namely, flavor test) to assess retro-nasal olfactory performance [29]. We have demonstrated that retro-nasal olfactory recognition in normal subjects is influenced by age and sex [30] and inversely correlates with Body Mass Index (BMI) [31]. Furthermore, patients with endocrine [29] and neurological diseases [32] had also a reduced flavor score.

Herein we investigated the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on chemosensory function, using both a self-reporting questionnaire on smell and flavor perception and a simplified flavor test that can be self-administered to isolated COVID-19 patients. Our data indicate that patients, after the infection, can recognize the tested aromas; however, they indicate to perceive flavors with a significant reduction in comparison to unaffected controls.

Materials and methods

Studied population

All participants were adults (≥18 years of age) and gave their written informed consent to the study. The research was performed in keeping with Italian Bioethics Law and the Declaration of Helsinki. The flavor test has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the Federico II University of Napoli (IDs 253/13 and 93/19) and the study has been registered to ClinicalTrial.org (NCT04840966). Nineteen hospitalized and 37 home isolated COVID-19-positive patients were enrolled for the study. Diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed by PCR of nasopharyngeal swab. Only patients with no critical conditions and able to understand the protocol were recruited. No patient reported nasal obstruction nor previous nasal diseases. Fifty-five healthy COVID-19 swab-negative volunteers were enrolled as controls.

Questionnaires and self-evaluation

All the enrolled subjects received an instruction form with explanation of definition and differences among smell, taste, and flavor. Participants also received a self-evaluation questionnaire (fig. S1) to record personal data, anamnestic and current information on health status. Date of positivity for the nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 virus and list of symptoms (cold, sore throat, headache, muscle aches, fatigue, fever, gastrointestinal problems, dyspnea, cough, hyposmia, hypogeusia, other) were recorded for all the patients. Finally, patients were asked to score their subjective chemosensory function (smell and flavor) before and after COVID-19 using a 0–10 scale with 0 corresponding to “no smell/flavor perception” and 10 corresponding to “excellent smell/flavor perception.”

Modified flavor score test

The original flavor test, consisting in 20 aromas and one control solution [29], has been modified and simplified to be self-administered. Four aromas, among those mostly recognized in the healthy population [30], were selected. Each aroma was diluted in sucrose solutions according to the manufacturer’s instruction, as previously described [29]. Four tubes with 0.5ml of aromatic solutions (coffee, “pure olfactory”; peppermint, “mixed olfactory-trigeminal”; banana, “a complex chemical mixture” [33]) or water (control) were provided to the enrolled subjects. Aromas were kindly provided by the manufacturer GIOTTI (Enrico Giotti spa, Scandicci, Firenze, Italy).

All subjects received an instruction sheet where the test procedure was explained: participants were invited to transfer the content of each tube in their mouth, hold it for few seconds and afterward, recognize the aroma contained in the tube, and choose one of the five possible options. Participants were also asked to score on a 1 to 10 scale the intensity of perceived stimulus for each aroma, considering 0 corresponding to “no flavor perception” and 10 corresponding to “excellent flavor perception.”

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 8 GraphPad software for macOS. Results were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Mann-Whitney test was used for comparisons across groups. Frequencies were used for categorical variables, and comparisons were made using the Fisher’s exact test. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to assess the occurrence of statistical associations between the variables under investigation. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05, with a two-sided level.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 111 subjects (19 hospitalized [HOS] and 37 home-isolated [HI] COVID-19 patients, and 55 healthy controls [CTRL]) were enrolled in the study. Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age for overall population was 41.52 ± 14.45 years. The HOS group presented a significantly higher age (p < 0.01) than HI and CTRL groups, while no age differences were found between HI and CTRL subjects. In the overall population median BMI was 25.82 kg/m2. No differences in BMI were present across the different study groups. The ratio between females and males enrolled in overall population, in CTRLS and HI, was similar. By contrast, in HOS group, there were more males (n = 17) than females (n = 2).

Questionnaires and self-assessed evaluation

The results of the questionnaire investigating COVID-19 symptoms are shown in Table 2. Several differences were present between the two groups of COVID-19 patients. In particular, HI presented more frequently than HOS cold, sore throat, headache, fatigue, and cough. The prevalence of STDs was reported to be similar among the two groups of patients.

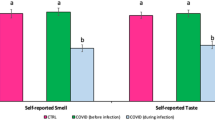

The quantitative impact of COVID-19 on chemosensory function was investigated asking to the patients to score on a 1–10 VAS their ability to recognize smell and flavors before and after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Results are shown in Fig. 1. Positive COVID-19 patients indicated that smell perception changed from a median score of 9.0 (8.0–10.0) to 8.0 (3.0–9.0) in HOS (p < 0.0001), and from 9.0 (9.0–10.0) to 7.0 (3.5–10.0) in HI (p < 0.0001). The difference across the two groups was not different, as indicated by two-way ANOVA analysis (Fig. 1A). Similarly, after virus exposure, flavor perception changed from a median score of 10.0 (9.0–10.0) to 8.0 (5.25–9.0) (p < 0.0001) in HOS and from 10.0 (9.0–10.0) to 7.0 (4.5–10.0) (p < 0.0001) in HI patients, respectively (Fig. 1B). Again, no differences across the two groups were detected with the two-way ANOVA test.

Quantitative self-estimated effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on smell (A) and flavor (B). Chemosensory function was investigated asking the patients to score on a 1–10 scale their ability to recognize smell and flavors before (pre) and after (post) the infection. Median scores and IQR are shown. No differences across the HOS and HI groups were detected using the two-way ANOVA test. HOS hospitalized COVID-19, HI home-isolated COVID-19. ***p < 0.0001

To understand whether patients recovered from their symptoms, 3 months after the test they were interviewed by phone. STDs had a median last of 14 (9–27) days for smell and 14 (9–28) for flavor alterations, with no significant differences between the two groups. Interestingly, STDs after 3 months were still present in 33.33% (smell) and 11.76% (flavor) of HI patients, while a complete recovery was reported from all HOS patients.

Modified flavor test: recognition and intensity

The tested aromas (banana, coffee, and peppermint) were recognized in either HOS or HI COVID-19 patients, similarly to the CTRL group. Only water was slightly less recognized by HOS patients (p = 0.0497). The results are shown in Table 3.

Finally, all participating subjects after recognizing each aroma were asked to score the intensity with which they perceived the flavor in the tubes using a 0–10 VAS scale. Results are shown in Fig. 2. Interestingly, although patients did not present qualitative alterations in terms of retro-nasal recognition, a significant quantitative impairment in chemosensory function was present in both HI and HOS COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 virus infection determines a reduction in the intensity of flavor perception. The degree of retro-nasal olfactory intensity impairment was not significantly different between HI and HOS patients.

Correlations between self-evaluated STD and flavor test

To evaluate whether there are relationships between the perceived alterations of the chemosensory abilities determined by SARS-CoV-2 infection and the results of the modified flavor test, Spearman’s correlation analyses were performed. In details, statistical correlations were evaluated between the results of post-infection subjective chemosensory function (either smell and flavor) and the total score (0 to 4) determined by the sum of properly recognized flavors used in the test (Fig. 3A and C), the average of the intensity scores reported by the patients (Fig. 3B and D), and the intensity scores for each of the four tested aromas (figs. S2 and S3). Only correlation between intensity of the “water” aroma and post-infection self-evaluation of flavor was not significant (p = 0.052), while all the other correlations were significant.

Discussion and conclusions

Deterioration of chemical senses has been suggested as a relevant manifestation and one of the best predictors of SARS-CoV-2 infection [34,35,36,37]. Our study aimed to evaluate retro-nasal olfaction in hospitalized and home-isolated patients following SARS-CoV-2 infection using a self-assessment questionnaire and — for the first time — a self-administered flavor test. Overall, our results demonstrated a quantitative but not a qualitative impairment in flavor perception in COVID-19 patients, regardless the severity of the disease.

The original flavor test [29] has been simplified, with the great advantage to be self-administrable for COVID-19 patients in isolation, without any risk to health professionals. In this form of the test, a pure olfactory stimulus (coffee), a mixed olfactory-trigeminal stimulus (peppermint), and a complex chemical mixture (banana) [33, 38,39,40] were selected among the 20 aromas included in the original flavor test. In addition, these 3 stimuli were chosen mainly because easily recognizable in the large part of the general population during the validation test [30]. As reported in recent literature, the aroma categories were selected to contain both odors with little to no trigeminal sensation and odors with mixed sensations of odor and trigeminal in various degree [41, 42]. Water was included among the test solutions as control. Many of the chemosensory tests used in the recent literature are costly and time-consuming to administer, and often require in-person interactions of the health care provider with potentially infectious patients. The modified flavor test proposed in this study is cheap, quick, and self-administrable.

The results of the present study indicate that there are no qualitative differences in flavor recognition between COVID-19 patients (either HOS or HI) and unaffected controls. In contrast, the intensity of the perceived aromas was significantly lower in patients compared to controls, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 infection is responsible for an impairment in chemosensory function. Chemosensory dysfunctions following COVID-19 seem to be different from other post-viral forms. A recent study has demonstrated that mechanisms of COVID-19 related olfactory dysfunction may reflect a specific involvement at the level of central nervous system [43]. Indeed, increasing evidence indicate that SARS-CoV-2 virus invades olfactory receptors and damages cell membrane of the first cranial nerve in nasal cavity and/or produces lesions in the central nervous system [44, 45]. Therefore, the direct effects of the virus on cortex, basal ganglia, and midbrain are associated with significant neuronal death [45]. This may account for reduce sensitivity to smells and flavors.

The lower intensity of perceived aromas was present regardless of the severity of the disease, since neither qualitative nor quantitative differences in flavor recognition were found between HOS and HI patients. This observation is discordant with previous reports, indicating that STDs are more frequently associated with mild forms of the disease [5, 22]. However, a phone interview performed 3 months after the test indicated that all HOS patients had a complete recovery from smell and flavor impairments, while these symptoms were still present in 33.33% and 11.75% of HI patients, respectively, suggesting that STDs last longer in patients with milder forms of the disease or, since the average age of HOS was than HI, in younger ones.

One of the critical points investigating chemosensory dysfunction is the difference that can be pointed out using self-evaluating or psychophysical tests. In healthy individuals the results of STDs evaluated with self-estimated methods are under-detected and under-reported in comparison to objective measures [46]. In contrast, their prevalence tends to be overestimated in COVID-19 patients [47]. Indeed, the self-evaluating assessments of STDs (with or without a Visual Analogic Scales [VAS]) [48, 49] can be influenced by several factors, including the bias determined by media attention to these symptoms.

The significant relationships observed between self-evaluated smell and flavor perception after SARS-CoV-2 infection and the results of the flavor test here proposed, indicate not only that our flavor test is cheap, quick to perform, and self-administrable, but also that the obtained results are superimposable to those obtained with a self-evaluating assessment of STDs. Most of the previous studies investigating STDs in COVID-19 patients were clinical surveys based on medical history and self-assessment. Only in some reports olfactory and gustatory functions following COVID-19 were measured with specific diagnostic tests [36, 50]. As previously indicated, this kind of tests may produce several bias and overestimate the relevance of alterations in chemosensory function. Indeed, as also recommended by recent papers, we suggested that a simple self-administered test could be a useful instrument to assess chemosensorial dysfunction in isolated/quarantined or hospitalized COVID-19 patients [13, 41]. Herein, for the first time, we propose a novel, simple, and reliable test that can be provided to COVID-19 patients for self-administration.

We are aware that this study has some limitations, first the absence of comparisons between retro-nasal and ortho-nasal olfaction as well as taste-testing. Nevertheless, it should be considered that evaluation of ortho-nasal olfaction requires the presence and the interaction with a healthy professional, with a relative long exposure to potentially infectious patients.

In addition, it should be noted that, in the examined study population, the HOS group was older than HI and CTRL groups, and that the prevalence of males was higher in HOS groups. These can be potential limitations, since age and sex may influence the flavor test results [30]. However, these data are in line with what reported in the literature. Indeed, severe clinical manifestations of the COVID-19 are more frequent in the elderly population, often requiring hospitalization [51, 52], and the prevalence of severe manifestations of COVID-19 is higher in males than in females [53].

In conclusion, in this study we propose a novel, simple, and self-administering chemosensory test to evaluate retro-nasal olfaction in isolated COVID-19-positive patients. The test demonstrated that the COVID-19 patients, regardless of the severity of the symptoms, can recognize aromatic solutions, but with a reduced intensity, compared to healthy controls. This suggests that the patients affected by SARS-CoV-2 virus present chemosensory impairment, and the modified “flavor test” could be a novel potential self-administering objective screening test STDs in COVID-19 patients.

References

Cantone E, Gamerra M (2020) The biometeorology of COVID-19: a novel therapeutic strategy? Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 63 (4):202-204. https://doi.org/10.14712/18059694.2020.65

Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M (2020) Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA 323(20):2052–2059. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6775

Welge-Lussen A, Wolfensberger M (2006) Olfactory disorders following upper respiratory tract infections. Advances in oto-rhino-laryngology 63:125–132. https://doi.org/10.1159/000093758

Gerkin RC, Ohla K, Veldhuizen MG et al (2020) Recent smell loss is the best predictor of COVID-19: a preregistered, cross-sectional study. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.22.20157263

Yan CH, Faraji F, Prajapati DP et al (2020) Self-reported olfactory loss associates with outpatient clinical course in COVID-19. International forum of allergy & rhinology 10(7):821–831. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22592

Hopkins C, Vaira LA, De Riu G (2020) Self-reported olfactory loss in COVID-19: is it really a favorable prognostic factor? International forum of allergy & rhinology 10(7):926. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22608

Sociedad.Espanola.de.Neurologia. https://www.sen.es/noticias-y-actividades/222-noticias/covid-19-informacion-para-pacientes/2663-covid-recomendaciones-de-la-sociedad-espanola-de-neurologia-sen-en-relacion-con-la-perdida-de-olfato-como-posible-sintoma-precoz-de-infeccion-por-covid-19.

Paderno A, Schreiber A, Grammatica A et al (2020) Smell and taste alterations in COVID-19: a cross-sectional analysis of different cohorts. International forum of allergy & rhinology 10(8):955–962. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22610

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181 (2):271-280 e278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052

Perrotta F, Matera MG, Cazzola M, Bianco A (2020) Severe respiratory SARS-CoV2 infection: does ACE2 receptor matter? Respir Med 168:105996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105996

Gamerra M, de Corso E, Cantone E (2021) COVID-19: the crucial role of the nose. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 87(1):118–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.08.001

Guedj E, Million M, Dudouet P et al (2021) (18)F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in post-SARS-CoV-2 infection: substrate for persistent/delayed disorders? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 48(2):592–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-020-04973-x

Marchese-Ragona R, Restivo DA, De Corso E et al (2020) Loss of smell in COVID-19 patients: a critical review with emphasis on the use of olfactory tests. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 40 (4):241-247. https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-N0862

Lima MA, Silva MTT, Oliveira RV et al (2020) Smell dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: more than a yes-no question. J Neurol Sci 418:117107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.117107

Moein ST, Hashemian SMR, Mansourafshar B et al (2020) Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. International forum of allergy & rhinology. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22587

Lechner M, Patel ZM, Philpott C, Lund VJ (2020) Olfactory loss of function as a possible symptom of COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1589

Brookes NRG, Fairley JW, Brookes GB (2020) Acute olfactory dysfunction—a primary presentation of COVID-19 infection. Ear Nose Throat J:145561320940119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561320940119

Moein ST, Hashemian SM, Tabarsi P, Doty RL (2020) Prevalence and reversibility of smell dysfunction measured psychophysically in a cohort of COVID-19 patients. International forum of allergy & rhinology. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22680

Bagnasco D, Passalacqua G, Braido F et al (2021) Quick Olfactory Sniffin’ Sticks Test (Q-Sticks) for the detection of smell disorders in COVID-19 patients. World Allergy Organ J 14(1):100497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100497

Mazzoli M, Molinari MA, Tondelli M et al (2021) Olfactory function and viral recovery in COVID-19. Brain Behav:e02006. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2006

Lechien JR, Journe F, Hans S et al (2020) Severity of anosmia as an early symptom of COVID-19 infection may predict lasting loss of smell. Front Med (Lausanne) 7:582802. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.582802

Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR et al (2020) Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 277(8):2251–2261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1

Burdach KJ, Doty RL (1987) The effects of mouth movements, swallowing, and spitting on retronasal odor perception. Physiol Behav 41(4):353–356

Small DM, Voss J, Mak YE et al (2004) Experience-dependent neural integration of taste and smell in the human brain. J Neurophysiol 92(3):1892–1903. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00050.2004

Blankenship ML, Grigorova M, Katz DB, Maier JX (2019) Retronasal odor perception requires taste cortex, but orthonasal does not. Curr Biol 29 (1):62-69 e63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.011

Espinosa Diaz M (2004) Comparison between orthonasal and retronasal flavour perception at different concentrations. Flavour Fragr J 19:499–504

Goldberg EM, Wang K, Goldberg J, Aliani M (2018) Factors affecting the ortho- and retronasal perception of flavors: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 58(6):913–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2016.1231167

Chaaban N, Hoier A, Andersen BV (2021) A detailed characterisation of appetite, sensory perceptional, and eating-behavioural effects of COVID-19: self-reports from the acute and post-acute phase of disease. Foods 10 (4). 10.3390/foods10040892

Maione L, Cantone E, Nettore IC et al (2016) Flavor perception test: evaluation in patients with Kallmann syndrome. Endocrine 52(2):236–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-015-0690-y

Nettore IC, Maione L, Desiderio S et al (2020) Influences of age, sex and smoking habit on flavor recognition in healthy population. International journal of environmental research and public health 17 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030959

Nettore IC, Maione L, Palatucci G et al (2020) Flavor identification inversely correlates with body mass index (BMI). Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases : NMCD. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2020.04.005

De Rosa A, Nettore IC, Cantone E et al (2019) The flavor test is a sensitive tool in identifying the flavor sensorineural dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology 40(7):1351–1356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-019-03842-2

Sollai G, Tomassini Barbarossa I, Usai P, Hummel T et al (2020) Association between human olfactory performance and ability to detect single compounds in complex chemical mixtures. Physiol Behav 217:112820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.112820

Mehraeen E, Behnezhad F, Salehi MA et al (2020) Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions due to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a review of current evidence. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06120-6

Walker A, Pottinger G, Scott A, Hopkins C (2020) Anosmia and loss of smell in the era of COVID-19. BMJ 370:m2808. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2808

Niklassen AS, Draf J, Huart C et al (2021) COVID-19: recovery from chemosensory dysfunction. A multicentre study on smell and taste. Laryngoscope. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29383

Gerkin RC, Ohla K, Veldhuizen MG et al (2021) Recent smell loss is the best predictor of COVID-19 among individuals with recent respiratory symptoms Chemical senses 46. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjaa081

Romer M, Lehrner J, Van Wymelbeke V et al (2006) Does modification of olfacto-gustatory stimulation diminish sensory-specific satiety in humans? Physiol Behav 87(3):469–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.11.015

Leijon SCM, Neves AF, Breza JM et al (2019) Oral thermosensing by murine trigeminal neurons: modulation by capsaicin, menthol and mustard oil. J Physiol 597(7):2045–2061. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP277385

Pal P, Shepherd D, Hamid N, Hautus MJ (2019) The use of freeze-dried retronasal stimuli to assess olfactory function. Clin Otolaryngol 44(5):770–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13389

Iravani B, Arshamian A, Ravia A et al (2020) Relationship between odor intensity estimates and COVID-19 prevalence prediction in a Swedish population. Chem Senses. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjaa034

Konstantinidis I, Delides A, Tsakiropoulou E et al (2020) Short-term follow-up of self-isolated COVID-19 patients with smell and taste dysfunction in Greece: two phenotypes of recovery. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 82(6):295–303. https://doi.org/10.1159/000511436

Huart C, Philpott C, Konstantinidis I et al (2020) Comparison of COVID-19 and common cold chemosensory dysfunction. Rhinology. https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin20.251

Klopfenstein T, Zahra H, Kadiane-Oussou NJ et al (2020) New loss of smell and taste: uncommon symptoms in COVID-19 patients in Nord Franche-Comte cluster, France. Int J Infect Dis 100:117–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.012

Saussez S, Lechien JR, Hopkins C (2020) Anosmia: an evolution of our understanding of its importance in COVID-19 and what questions remain to be answered. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06285-0

Hoffman HJ, Rawal S, Li CM, Duffy VB (2016) New chemosensory component in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): first-year results for measured olfactory dysfunction. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 17 (2):221-240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-016-9364-1

Pinna FdR, Brandão Neto D, Fornazieri MA, Voegels RL (2020) Olfaction and COVID: the little we know and what else we need to know. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol (EFirst). https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1713143

Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, Fastenberg JH, Tham T (2020) The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 163(1):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820926473

Fantozzi PJ, Pampena E, Di Vanna D et al (2020) Xerostomia, gustatory and olfactory dysfunctions in patients with COVID-19. Am J Otolaryngol 41(6):102721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102721

Mullol J, Alobid I, Marino-Sanchez F et al (2020) The loss of smell and taste in the COVID-19 outbreak: a tale of many countries. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 20(10):61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-020-00961-1

Du RH, Liang LR, Yang CQ et al (2020) Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J 55 (5). https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00524-2020

Polidori MC, Sies H, Ferrucci L, Benzing T (2021) COVID-19 mortality as a fingerprint of biological age. Ageing Res Rev 67:101308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101308

Wenham C, Smith J, Morgan R, Gender, Group C-W (2020) COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 395(10227):846–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.N., E.C., and P.E.M.; methodology, G.P., F.F., R.M., M.N., E.M., and M.F.; data curation, I.C.N, P.U., and P.E.M; writing—original draft preparation, P.E.M and I.C.N.; writing—review and editing, P.U., E.C., L.M., and A.C.; supervision, P.E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The research was performed in keeping with Italian Bioethics Law and the Declaration of Helsinki. The flavor test has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the Federico II University of Napoli (IDs 253/13 and 93/19).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nettore, I.C., Cantone, E., Palatucci, G. et al. Quantitative but not qualitative flavor recognition impairments in COVID-19 patients. Ir J Med Sci 191, 1759–1766 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02786-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02786-x