Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is an effective treatment for morbid obesity. Current average length of hospital stay (LOS) after RYGB is 2–3 days and 30-day readmission rate is 8–13 %. The aim of our study is to evaluate the effect of routine gastrostomy tube placement in perioperative outcomes of RYGB patients.

Methods

Between January 2008 and December 2010, a total of 840 patients underwent RYGB at our institution. All RYGB patients had gastrostomy tube placed, which was kept for 6 weeks. A retrospective review of a prospectively collected database was performed for all RYGB patients, noting the outcomes and complications of the procedure.

Results

Average LOS in our patient population was 1.1 days (range, 1–14 days), and 824 (98.3 %) patients were discharged on postoperative day 1. Readmissions within 30 days after the index RYGB was observed in 31 (3.7 %) patients. Reasons included abdominal pain (n = 14), nausea/vomiting (n = 6), gastrostomy tube-related complications (n = 5), chest pain (n = 3), allergic reaction (n = 1), urinary tract infection (n = 1), and dehydration (n = 1). Of these readmitted patients, nine (1.1 %) patients required reoperations due to small bowel obstruction (n = 5), perforated anastomotic ulcer (n = 1), anastomotic leak (n = 1), subphrenic abscess (n = 1), and appendicitis (n = 1).

Conclusions

Routine gastrostomy tube placement in the gastric remnant at the time of RYGB seems to have contributed to our short LOS and low 30-day readmission rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of morbid obesity has rapidly increased since 1990 [1]. As a consequence, along with the development of the laparoscopic approach [2, 3], the number of bariatric procedures performed soared [4]. A single insurance company observed an increase of 800 % in bariatric procedures within 5 years (1999–2004) [5].

Bariatric procedure gained acceptance due to its safety and effectiveness as a durable treatment option for morbid obesity and its comorbidities [6]. Despite its safety, complications resulting in emergency room visits, readmissions, and reoperations have been reported, and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was noted to be with the highest readmission rate [7, 8]. The 30-day readmission rate was 8–13 % due to nausea, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, and dehydration [9, 10], and emergency room visits were reported to be as high as 31 % due to abdominal pain and vomiting [11].

Currently, the median length of hospital stay (LOS) is 2–3 days for RYGB [8, 12], and various reports argued against discharging the patients on postoperative day (POD) 1 [10, 13]. Reasons for extended LOS included bleeding, intolerance of liquids, and abdominal pain [10].

Patients after RYGB may require access to the gastric remnant due to various reasons, such as distended gastric remnant, nutritional support, and drainage. However, percutaneous computed tomography (CT)-guided access to the gastric remnant can be challenging and has a failure rate of 9 %, requiring laparoscopic gastrostomy [14, 15]. Placement of gastrostomy tube in the gastric remnant at the time of gastric bypass procedure has been suggested for decompression and enteral feedings as well [16]. In addition, gastrostomy tube placement at the time of primary procedure would have significantly affected complication outcomes and even prevented emergency reoperations in micropouch gastric bypass patients [17].

The aim of our study is to evaluate and determine the perioperative outcome, LOS, and 30-day readmission rate when gastrostomy tube is placed at the gastric remnant as a routine procedure in RYGB patients.

Methods and Materials

After institutional review board approval and following the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines, the authors performed a retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database and medical chart review of 840 patients who underwent primary RYGB from January 2008 to December 2010. All patients had the gastrostomy tube placed at the time of RYGB.

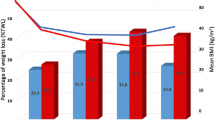

The population reviewed included 663 females and 177 males, with a mean age of 43.7 years (range, 17–88 years) and a preoperative mean body mass index (BMI) of 47.1 kg/m2 (range, 34.4–99.7 kg/m2) at the time of RYGB. The patient demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. RYGB was performed by one surgeon according to the National Institutes of Health criteria for the management of morbid obesity.

Surgical Technique

RYGB was performed using a six-trocar approach laparoscopically using four 5-mm trocars, one 10-mm trocar, and one 12-mm trocar. A window was created between the lesser curvature of the stomach and the lesser omentum above the foot of the crow to enter the lesser sac and preserve the nerve of Latarjet. The stomach was then transected along the lesser curvature to the angle of His, creating a pouch over the Edlich tube. All hiatal hernias were suture closed when present. The ligament of Treitz was identified, the jejunum was transected with a linear stapler at 40 cm, and the mesentery was left intact. The efferent limb was followed for 75 cm for patients with BMI <45 kg/m2, 100 cm for BMI between 45 and 55 kg/m2, and 150 cm for BMI over 55 kg/m2, and jejunojejunostomy was performed using a linear stapler. The Roux limb was brought in an antecolic, antegastric fashion, and gastrojejunal anastomosis was created. Petersons’ defect and mesenteric defect were both closed.

A gastrostomy was made at the anterior gastric wall of the gastric remnant using harmonic scalpel. A gastrostomy tube was placed at the gastrostomy site, and the site was closed using two layers of running purse-string suture using 2-0 Polysorb Endo Stitch™. The closure was reinforced with omental patch. After placing the gastrostomy tube, the gastric remnant was not pulled close to the abdominal wall and was left in its place. The tube was kept to gravity drainage for <24 h and clamped before the patient was discharged. This procedure was intended to reduce gastric remnant staple line disruption, allow the surgeon to test the remnant staple line, and provide the patient with an avenue for feeding and hydration postoperatively. All patients were given instructions to use gastrostomy bolus feeding and/or fluid supplement in cases of severe nausea or intolerance to food. Two patients were converted to open procedure due to extensive adhesions.

Results

Length of Hospital Stay

Of our 838 patient population, excluding 2 patients with open procedure, the mean LOS was 1.1 days (range, 1–14 days) and the median was 1 day. Majority of our patients (824, 98.3 %) were discharged on POD 1 (Fig. 1). Due to nausea and uncontrolled postoperative pain, seven (0.8 %) patients were discharged on POD 2.

Six (0.7 %) patients stayed longer than 3 days after the operation (Table 2). Two patients presented postoperative tachycardia at a rate of 125–140 bpm on POD 1. Upper gastrointestinal imaging and methylene blue testing were performed to exclude leak, and testings were negative in both patients. One of these two patients showed bilateral atelectasis and hypovolemic lung due to obesity hypoventilation syndrome. This patient got well and was discharged on POD 4. The other patient also showed hypotension of 100/58, was managed conservatively, and was discharged on POD 6.

One patient developed pulmonary edema and was on respirator. Gastrograffin upper gastrointestinal studies were performed to exclude leak, and echocardiogram ruled out myocardial infarction. This patient did better and was discharged on POD 4.

One patient developed acute myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation on POD 1, required percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and was discharged on POD 9. She was readmitted for left chest pain 3 days after discharge and was managed conservatively. One patient had extensive lysis of adhesions at the time of RYGB, which subsequently developed prolonged ileus postoperatively. He was treated conservatively and discharged on POD 11.

One patient had an episode of focal stroke resulting in right monoplegia on the day of RYGB. She was treated conservatively with physical therapy and discharged on POD 14. None of our patients were reoperated before discharge.

30-Day Readmissions

There were 31 (3.7 %) patients who required 32 readmissions within 30 days after their index RYGB. Abdominal pain presented as the chief complaint in 14 (1.7 %) patients. Six (0.7 %) patients were readmitted because of nausea and/or vomiting, and five (0.6 %) patients had gastrostomy tube-related complications. Three (0.4 %) patients experienced shortness of breath and/or chest pain that required readmission. One (0.1 %) patient had an allergic reaction with hives, one (0.1 %) patient had urinary tract infection, and one (0.1 %) patient was dehydrated (Fig. 2; Table 3).

Of the 14 patients who were readmitted in regards to abdominal pain, 9 (1.1 %) required reoperations. Five patients were found to have small bowel obstruction, and reasons for small bowel obstruction included adhesions (n = 2), internal herniation at the mesenteric defect site (n = 2), and efferent loop obstruction (n = 1). One patient had perforated gastrojejunal anastomotic ulcer, one patient had anastomotic leak at the gastrojejunostomy, and one patient developed a subhepatic abscess which required exploratory laparotomy and drainage of the subhepatic abscess. One patient had appendicitis (Fig. 3).

Of these nine patients requiring reoperation, one patient developed respiratory failure and bilateral aspiration pneumonia after the repair of small bowel obstruction and had tracheostomy done 16 days after the procedure. Her condition improved and she was discharged 40 days after the reoperation. Another patient developed tachycardia, pulmonary edema, and subsequently, Candida albicans and Enterococcus faecalis infection. She was managed conservatively and discharged 15 days after the reoperation.

One patient was readmitted more than once in the 30-day period. She initially presented with abdominal pain and revisited the hospital 7 days after discharge due to abdominal pain. She was conservatively managed at both visits and eventually underwent stomal balloon dilatation due to persistent nausea and vomiting 92 days after her index procedure. No death occurred within 30 days after the index procedure.

Complications

Eight (0.9 %) patients developed complications related to the gastrostomy tube. Of these eight patients, four patients presented with gastrostomy tube site pain, two patients had gastrostomy tube site bleeding, and two had gastrostomy tube displacement (Table 4).

The gastrostomy tube of one patient did not come out easily after 6 weeks and she was complaining of abdominal pain and discomfort around the gastrostomy tube site. The tip of the gastrostomy tube was in the gastric lumen when checked with fluoroscopy. This patient was scheduled for diagnostic laparoscopy due to her pain and discomfort, but the tube came out easily with some drainage of gastric juice on the day of scheduled diagnostic laparoscopy. Thus, diagnostic laparoscopy was cancelled and the patient did well afterwards.

One patient was kept on gastrostomy tube more than 6 weeks due to malnutrition and had displaced gastrostomy tube 85 days after RYGB. This patient was readmitted for displaced gastrostomy tube and malnutrition and to rule out anastomotic ulcer. She underwent conservative management and did well.

Discussion

LOS and readmission rates are frequently used as parameters of successful bariatric surgery. Furthermore, LOS longer than 2 days was reportedly related to higher readmission rates within 30 days of discharge [9]. These two perioperative indicators also play a significant role in hospital costs. Huerta et al. [18] reported that when average LOS decreased from 4.05 to 3.17 days along with 1 % reduction in readmission rates, hospital costs reduced by 40 %.

Currently, although some centers discharge patients on POD 1, mean LOS for RYGB remains 2–3 days nationwide [8, 12, 19]. A recent report claimed that RYGB should not be predictably performed as a 23-h procedure using current surgical technology [10]. Another report stated that a 2-day LOS was safe and feasible for the vast majority of their patients [9]. Most common reasons for extended LOS for more than 4 days were bleeding, intolerance of liquids, nausea, and abdominal pain [9, 10].

Of our 838 patient population, 98.3 % were discharged on POD 1 as a consequence of gastrostomy tube placement. Gastrostomy tube was placed in the gastric remnant, as first described by Fobi et al. [20], to access the bypassed stomach. It was intended to provide the patient with a means for feeding and hydration postoperatively. We were able to feed the patients immediately after the operation, and only 0.8 % of our patients experienced nausea and pain that lengthened their LOS for one additional day. Two (0.2 %) patients had workups for possible leak and small bowel obstruction that required longer than 5 days of hospital stay. The placement of the gastrostomy tube enabled us to discharge patients early because patients were able to supplement themselves when they could not tolerate food or fluid by mouth.

Furthermore, access to the gastric remnant enabled us to evaluate remnant staple line and to prevent staple line disruption and gastric remnant leak. We believe that the majority of gastric leak from the gastric remnant goes unnoticed because the bypassed stomach is not readily available for evaluation. Nosher et al. [15] described the need for percutaneous gastrostomy after RYGB for dilatation of the bypassed stomach, and 75 % of his gastrostomy patients required the intervention within 30 days after the RYGB. Goitein et al. [14] performed CT-guided gastric remnant gastrostomy for distended gastric remnant, nutritional access, and remnant drainage after leak with 9 % failure rate requiring laparoscopic gastrostomy.

Dallal et al. [10] reported a 30-day readmission rate of 7.5 % mainly due to abdominal pain and/or vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, dehydration, and small bowel obstruction. Lancaster et al. [8] reported 3.6 % reoperation rate within 30 days after the index procedure in their prospective multicenter study. Our 30-day readmission rate and reoperation rate was significantly lower than these reports, with a readmission rate of 3.7 % and a reoperation rate of 1.1 %. We are confident that majority of readmissions within 30 days of the primary procedure were prevented by utilizing the gastrostomy tube for nutrition, hydration, and prevention of gastric remnant dilatation. We also believe that only the patients that required immediate medical and surgical attention were readmitted because 32.3 % of our readmitted patients required reoperation.

Only 0.9 % of patients developed complications of the gastrostomy tube, in the form of pain or bleeding around the gastrostomy site and displacement of the gastrostomy tube. We think these numbers are minimal, and none of these patients required surgical intervention.

Wood et al. [17] concluded that routine gastrostomy tube placement at the time of gastric bypass is not necessary in all patients. He stated that it is recommended only for patients who are at high risk for gastroenteric obstruction or an anastomotic leak. However, we argue that we cannot always predict patients with high risk. Moreover, we believe that routine gastrostomy tube not only prevented the need for reoperation but also decreased LOS and readmission rate, as shown in our study.

The weakness of our study is that it is a retrospective review of the database. Also, we were not able to compare this study with our own RYGB patients without the gastrostomy tube. However, we believe that a large enough number of patients were included in this study to validate our results. Most importantly, this is the first report of the effect of routine gastrostomy tube placement in perioperative outcomes of RYGB patients.

Conclusions

Routine gastrostomy tube placement in the gastric remnant at the time of RYGB seems to have contributed to our short LOS and low 30-day readmission rate.

References

Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, et al. Trends and correlates of class 3 obesity in the United States from 1990 through 2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1758–61.

Nguyen NT, Goldman C, Rosenquist CJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: a randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg. 2001;234:279–89.

Lujan JA, Frutos MD, Hernandez Q, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass in the treatment of morbid obesity: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg. 2004;239:433–7.

Steinbrook R. Surgery for severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1075–9.

Bradley DW, Sharma BK. Centers of excellence in bariatric surgery: design, implementation, and one-year outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:513–7.

Davis MM, Slish K, Caho C, et al. National trends in bariatric surgery, 1996–2002. Arch Surg. 2006;141:71–4.

Saunders J, Ballantyne GH, Belsley S, et al. One-year readmission rates at a high volume bariatric surgery center: laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, laparoscopic gastric bypass, and vertical banded gastroplasty–Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1233–40.

Lancaster RT, Hutter MM. Bands and bypasses: 30-day morbidity and mortality of bariatric surgical procedures as assessed by prospective, multi-center, risk-adjusted ACS-NSQUIP data. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2554–63.

Baker MT, Lara MD, Larson CJ, et al. Length of stay and impact on readmission rates after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:435–9.

Dallal RM, Trang A. Analysis of perioperative outcomes, length of hospital stay, and readmission rate after gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:754–8.

Cho M, Kaidar-Person O, Szomstein S, et al. Emergency room visits after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:104–9.

Dallal RM, Datta T, Braitman LE, et al. Medicare and Medicaid status predicts prolonged length of stay after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:592–6.

DeMaria EJ, Pate V, Warthen M, et al. Baseline data from American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery-designated Bariatric Surgery Centers of Excellence using the Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:347–55.

Goitein D, Gagne DJ, Papasavas PK, et al. Percutaneous computed tomography-guided gastric remnant access after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:651–5.

Nosher JL, Bodner LJ, Girgis WS, et al. Percutaneous gastrostomy for treating dilatation of the bypassed stomach after bariatric surgery for morbid obesity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1431–5.

Fobi MAL, Lee H. The surgical technique of the Fobi-pouch operation for obesity (the transected silastic vertical gastric bypass). Obes Surg. 1998;8:283–8.

Wood MH, Sapala JA, Sapala MA, et al. Micropouch gastric bypass: indications for gastrostomy tube placement in the bypassed stomach. Obes Surg. 2000;10:413–9.

Huerta S, Heber D, Sawicki MP, et al. Reduced length of stay by implementation of a clinical pathway for bariatric surgery in an academic care center. Am Surg. 2001;67:1128–35.

McCarty TM, Arnold DT, Lamont JP, et al. Optimizing outcomes of bariatric surgery: outpatient laparoscopic gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2005;242:494–8.

Fobi MA, Chicola K, Lee H. Access to the bypassed stomach after gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 1998;8:289–95.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moon, R., Teixeira, A., Potenza, K. et al. Routine Gastrostomy Tube Placement in Gastric Bypass Patients: Impact on Length of Stay and 30-Day Readmission Rate. OBES SURG 23, 216–221 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0835-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0835-5