Abstract

Background

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is one of the most commonly used instruments to assess depression in persons with obesity. While it has been validated in normal and psychiatric populations, in obese populations, its validity remains uncertain. This study aimed to investigate the validity and reliability of the BDI-IA and BDI-II in severely obese bariatric surgery candidates.

Methods

Consecutive new candidates at a bariatric surgery clinic were invited to participate in the study by their consulting surgeon. All candidates were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (SCID-I); 118 completed the BDI-IA and 83 completed the BDI-II. Two hundred one patients (response rate, 88 %) participated in the study. The current sample (82 % female) had an average body mass index of 42.83 ± 6.34 and an average age of 45 ± 12 years.

Results

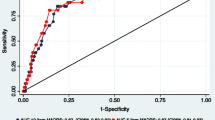

Based on the SCID-I, 54 candidates (26.9 %) met the criteria for a mood disorder, with 37 meeting the criteria for current major depressive disorder. Individuals diagnosed with a clinical mood disorder had significantly higher scores on the BDI (BDI-IA, 23.59 ± 9.69 vs. 12.76 ± 8.29; BDI-II, 22.93 ± 5.22 vs. 11.25 ± 8.44). Our results indicated that, as a screening tool for a clinical mood disorder, the BDI-II had an optimal cutoff of 13, with a sensitivity of 100 and specificity of 67.75.

Conclusions

Results indicated that the BDI-IA should not be used as a tool to measure depressive symptomatology in obese bariatric surgery candidates. No cutoff was identified with adequate sensitivity and specificity, and over 20 % of patients were misclassified. As a screening tool for a clinical mood disorder, the BDI-II was adequate; however, prevalence rates were significantly overestimated.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

ABS 1998. Mental health and wellbeing: profile of adults, Australia, 1997. Canberra: ABS: ABS Cat. No. 4326.0.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K, et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):824–30.

Heo M, Pietrobelli A, Fontaine KR, et al. Depressive mood and obesity in US adults: comparison and moderation by sex, age, and race. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006;30(3):513–9.

Roberts RE, Deleger S, Strawbridge WJ, et al. Prospective association between obesity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(4):514–21.

Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, et al. Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: relationship to obesity and functional health status. Am J Psych. 2007;164(2):328–34. quiz 74.

Mauri M, Rucci P, Calderone A, et al. Axis I and II disorders and quality of life in bariatric surgery candidates. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(2):295–301.

Mühlhans B, Horbach T, de Zwaan M. Psychiatric disorders in bariatric surgery candidates: a review of the literature and results of a German prebariatric surgery sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(5):414–21. Epub 2009/08/26.

Rosenberger PH, Henderson KE, Grilo CM. Psychiatric disorder comorbidity and association with eating disorders in bariatric surgery patients: a cross-sectional study using structured interview-based diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(7):1080–5.

Bauchowitz AU, Gonder-Frederick LA, Olbrisch ME, et al. Psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery candidates: a survey of present practices. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(5):825–32.

Fabricatore AN, Crerand CE, Wadden TA, et al. How do mental health professionals evaluate candidates for bariatric surgery? Survey results. Obes Surg. 2006;16(5):567–73.

Love RJ, Love AS, Bower S, et al. Impact of antidepressant use on gastric bypass surgery patients' weight loss and health-related quality-of-life outcomes. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(6):478–86.

Pontiroli AE, Fossati A, Vedani P, et al. Post-surgery adherence to scheduled visits and compliance, more than personality disorders, predict outcome of bariatric restrictive surgery in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2007;17(11):1492–7.

Walfish S, Vance D, Fabricatore AN. Psychological evaluation of bariatric surgery applicants: procedures and reasons for delay or denial of surgery. Obes Surg. 2007;17(12):1578–83.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II). San Antonio, TX: Psychology Corporation; 1996.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71.

Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993.

Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. AACE/TOS/ASMBS Guidelines. Obesity. 2009;17(S1):S3–72.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psych Rev. 1988;8:77–100.

Krukowski RA, Friedman KE, Applegate KL. The utility of the Beck Depression Inventory in a bariatric surgery population. Obes Surg. 2008.

Plumb MM, Holland J. Comparative studies of psychological function in patients with advanced cancer—I. Self-reported depressive symptoms. Psychosom Med. 1977;39(4):264–76.

Grant D, Almond MK, Newnham A, et al. The Beck Depression Inventory requires modification in scoring before use in a haemodialysis population in the UK. Neph Clin Prac. 2008;110:c33–8.

Smith M, Hong B, Robson A. Diagnosis of depression in patients with end-stage renal disease: comparative analysis. Am J Med. 1985;79:160–6.

Saules KK, Wiedemann A, Ivezaj V, et al. Bariatric surgery history among substance abuse treatment patients: prevalence and associated features. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(6):615–21. Epub 2010/03/09.

Mitchell JE, Steffen KJ, de Zwaan M, et al. Congruence between clinical and research-based psychiatric assessment in bariatric surgical candidates. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(6):628–34. Epub 2010/08/24.

Dalrymple KL, Galione J, Hrabosky J, et al. Diagnosing social anxiety disorder in the presence of obesity: implications for a proposed change in DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(5):377–82. Epub 2011/02/11.

Forkmann T, Vehrena T, Boechera M, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Beck Depression Inventory in cardiologic inpatients: how useful is the conventional cut-off score? J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:347–52.

Lustman PJ, Clouse RE, Griffith LS, et al. Screening for depression in diabetes using the Beck Depression Inventory. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:24–31.

Hayden MJ, Dixon JB, Dixon ME, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Beck Depression Inventory in obese individuals seeking surgery. Obes Surg. 2010;20(4):432–9.

Hayden MJ, Dixon JB, Dixon ME, et al. Characterization of the improvement in depressive symptoms in the obese following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011;21(3):328–35.

First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. (SCID-I/NP). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

Kalarchian MA, Wilson GT, Brolin RE, et al. Binge eating in bariatric surgery patients. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23(1):89–92.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, et al. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67(3):588–97.

Hsiao JK, Batrtko JJ, Potter WZ. Receiver operating characteristic methods and psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:664–7.

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983;148(3):839–43.

Arnau RC, Meagher MW, Norris MP, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychol. 2001;20(2):112–9. Epub 2001/04/24.

Furlanetto LM, Mendlowicz MB, Romildo Bueno CJ. The validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form as a screening and diagnostic instrument for moderate and severe depression in medical inpatients. J Affect Disord. 2005;86:87–91.

Strik J, Honig A, Lousberg R, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of observer and self-report questionnaires in major and minor depression following myocardial infarction. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:423–8.

Conflict of Interest

The Centre for Obesity Research and Education (CORE) received funding from Allergan for research support. The grant is not tied to any specified research projects and Allergan have no control of the protocol, analysis, and reporting of any studies. CORE also receives a grant from Applied Medical towards the educational programs. Dr. Wendy Brown reported receiving an honorarium from Allergan for attending a scientific advisory panel in London in 2009. Dr. Paul O’Brien reported having written a patient information book entitled “The LAP-BAND Solution: A Partnership for Weight Loss” which was published by Melbourne University Publishing in 2007. Most copies are given to patients without charge, but he reports that he derives a financial benefit from the copies that are sold. He also reports receiving compensation as the national medical director of the American Institute of Gastric Banding, a multicenter facility, based in Dallas, TX, USA that treats obesity predominantly by gastric banding. No other authors reported disclosures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hayden, M.J., Brown, W.A., Brennan, L. et al. Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory as a Screening Tool for a Clinical Mood Disorder in Bariatric Surgery Candidates. OBES SURG 22, 1666–1675 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0682-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0682-4