Abstract

The Anthropocene presents a set of interlinked sustainability challenges for humanity. The United Nations 2030 Agenda has identified 17 specific Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a way to confront these challenges. However, local initiatives have long been addressing issues connected to these goals in a myriad of diverse and innovative ways. We present a new approach to assess how local initiatives contribute to achieving the SDGs. We analyse how many, and how frequently, different SDGs and targets are addressed in a set of African initiatives. We consider goals and targets addressed by the same initiative as interacting between them. Then, we cluster the SDGs based on the combinations of goals and targets addressed by the initiatives and explore how SDGs differ in how local initiatives engage with them. We identify 5 main groups: SDGs addressed by broad-scope projects, SDGs addressed by specific projects, SDGs as means of implementation, cross-cutting SDGs and underrepresented SDGs. Goal 11 (sustainable cities & communities) is not clustered with any other goal. Finally, we explore the nuances of these groups and discuss the implications and relevance for the SDG framework to consider bottom-up approaches. Efforts to monitor the success on implementing the SDGs in local contexts should be reinforced and consider the different patterns initiatives follow to address the goals. Additionally, achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda will require diversity and alignment of bottom-up and top-down approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2030 Agenda) was agreed in 2015 after a broad and inclusive process of thematic and national consultation with national parliaments of the Member States, local authorities, civil society organizations, citizens, researchers and private sector actors around the world. This effort to include a wide range of voices is aligned with the underlying principle of the 2030 Agenda, namely that all 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and associated 169 targets are integrated and indivisible (United Nations 2015a). This principle aims to balance the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. Unlike the previous UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the 2030 Agenda is focused on capturing complex interdependencies between goals and targets, illustrated by the many cross-references between targets and indicators and their explicit contextualization into social–ecological systems (Norström et al. 2014).

Scholars have long argued the need to integrate economic, social and ecological dimensions in achieving sustainable development, arguing that human and natural systems are inseparably linked and should be dealt with as social–ecological systems (Berkes and Folke 1998). Folke et al. (2016) emphasize that “the biosphere serves as the foundation upon which prosperity and development ultimately rest” (Folke et al. 2016, p. 4). Raworth’s recent visual framework on the safe and just space for humanity (Raworth 2012, 2017), for instance, highlights that sustainable development requires staying within planetary boundaries (Rockström et al. 2009; Steffen et al. 2015) while ensuring people have the resources needed—such as food, water, health care, and energy—to fulfil their human rights. It is in this environmentally safe and socially just space in which inclusive and sustainable economic development takes place (Raworth 2012, 2017). Such approaches highlight the complexity that underlies the integrated and indivisible nature of SDGs.

Filling the gaps: analysing the interactions between SDGs through local lens

Achieving the SDGs will hinge on a better understanding of the interactions occurring among the different social, economic and ecological goals and targets. Some targets are clearly synergistic, indicating efficiency gains in looking for actions that contribute to multiple goals and targets. For example, improving electricity access through solar technologies (Goal 7) enables students to spend more time studying (Goal 4) and improves access to information communication technologies (Goal 9). It simultaneously reduces the use of solid fuels and kerosene for cooking and lighting (Goal 7) and its related air pollution and diseases (Goal 3) (Collste et al. 2017). On the flip side, there are other goals and targets that present obvious trade-offs to their mutual achievement. For example, investing in biofuels to increase the share of renewable energy (Goal 7) and contribute to climate change reduction (SDG 13) may have negative consequences on securing access to food (Goal 2) (Searchinger et al. 2008).

Understanding the synergistic relationships and trade-offs between the SDGs, and the 169 SDG targets, can support more coherent and effective decision making (Nilsson et al. 2016, 2018; ICSU 2017; Pradhan et al. 2017; Weitz et al. 2018). While some research has appeared in the last years to deal with this issue, gaps still remain unaddressed. Weitz et al. (2018) pointed out three main approaches that have been taken when assessing and conceptualizing the interactions between SDGs. First, the most common approach when addressing SDGs interactions is focused on studying one or some specific goals and then exploring how it relates or affects other goals (e.g., Vladimirova and Le Blanc 2016; Nilsson et al. 2018; Jaramillo et al. 2019). A second approach analyses how a subset of goals or targets interacts among themselves (e.g., Collste et al. 2017). Finally, a third approach focused on assessing interaction across the whole (or a big) set of goals and targets (e.g., Nilsson et al. (2016)’s scoring system; also used in Weitz et al. (2018) and Allen et al. (2019)); however, this approach remains under-developed (Weitz et al. 2018).

Importantly, most of the research has focused on identifying potential rather than empirical linkages. For example, Boas et al. (2016)’s theoretical approach, Le Blanc (2015)’s semantic analysis of the 2030 Agenda, or ICSU (2017), Nilsson (2017) and Weitz et al. (2018)’s expert judgments characterizations. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, all research on SDG interactions to date has focused at global, regional or national scales. However, the 2030 Agenda also includes the relevance of how local action can contribute to achieving the SDGs, as it establishes that “governments and public institutions will also work closely on implementation with regional and local authorities” (the 2030 Agenda, p.11). Thus, “despite the need for global outcomes, most implementation [of the SDGs] will be local” (Smith et al. 2018; p. 1483), and incorporating current knowledge on the dynamics of social change processes at multiple scales will be critical to achieving the SDGs (Norström et al. 2014). Multiple academics and practitioners have emphasized the importance of the context, as the interlinkages and overlaps among goals and targets will vary as a function of the local realities and contexts where they are implemented (Reed et al. 2015; Stephens et al. 2018). Satterthwaite (2016, 2018) advocates for the incorporation of “local lens” or “indicators for local action” for the implementation of SDGs, highlighting how interventions should be designed to specific development needs of particular context, rather than being blanket interventions applied across systems. Furthermore, our understanding of how change occurs in complex social–ecological systems has shown that the local can shape the global, through different processes such as providing response diversity, local contextualization and social learning, aggregation or via contagion (see, Geels 2002; Gunderson and Holling 2002; Olsson et al. 2006; Geels and Schot 2007; Moore et al. 2014). Though different national contexts can lead to different SDG interactions (Weitz et al. 2018), there are no studies assessing whether local interactions of SDGs differ from national level interactions.

In this study we empirically analyse a related set of bottom-up sustainability initiatives to identify interactions among SDGs at local scales. We use initiatives identified by the Seeds of Good Anthropocenes project (https://goodanthropocenes.net/). This project has identified a set of diverse existing initiatives or “seeds” from all around the world that could, given the correct conditions, have the potential to catalyse more radical transitions towards a sustainable future. In doing so, many of these initiatives address many of the SDG targets.

Coding 69 locally grounded African initiatives from the Seeds database to relate them to the 169 SDG targets, we analysed the interactions occurring between these targets and corresponding goals. We focussed on African iniatives, to encompass the complexity of the 2030 Agenda formulation while keeping the attention on local realities and contexts. Specifically we (1) analysed the frequency of the different 169 targets in the local African initiatives (2) described the patterns of interaction appearing among the targets and goals; and (3) analysed how characteristics of SDGs explained their uptake and uses. This paper contributes to advancing practical research on how to use systems thinking and analysis to support the assessment of SDG targets achievement at local scales.

Methodology

Data collection

The Seeds of Good Anthropocenes database has collected information on approximately 500 local sustainability initiatives. These initiatives—or “seeds”—are currently marginal but may supercede dominant structures in the future, under the right conditions. These seeds have been collected from broad networks of sustainability scientists and practitioners through multiple workshops and conference sessions (for more details on these processes themselves see https://goodanthropocenes.net/resources/). Furthermore, seeds have also been collected through an online questionnaire (https://goodanthropocenes.net/send-us-your-seed/). Key attributes of the seeds have been documented, based on variables such as the challenges it addresses, its innovative aspects or the number and type of people involved (see Bennett et al. (2016) and Pereira et al. (2018b) for more information).

Out of the 75 seeds from the Seeds database that were located in Africa, we analysed 69 seeds (Fig. 1). The remaining 6 initiatives were not considered as we could not find enough information related to them in a web search. Africa has been widely identified as a priority area in the context of the 2030 Agenda, highlighting the need to focus on the full achievement of the SDGs in this continent and placing special attention to goals that have being left out in the past (United Nations 2012, 2015a, b; see Table 1). Analysing the African seeds as examples of bottom-up SDG implementation provides valuable information into the complex local patterns of interactions (positive and negative) that potentially exists between goals and targets. This complexity is fostered by the great diversity of seeds, ranging from green urbanism to agroecology or biodiversity conservation (Bennett et al. 2016). This diversity is present in the 69 seeds included in the analysis; however, these seeds are only part of the variety of African experiences and North and South–West regions of the African continent are not well represented. This geographic bias is not a key point for this analysis, which is focused on the types of activities developed by the seeds rather than the relation of these patterns to their geographic context.

Distribution of the African seed initiatives. These initiatives can be part of a an international network/organization (n = 12); b an African network/organization (n = 4); and they can also appear as c individual case studies (n = 53). For the international networks/organizations, the African cases studies are represented in the map. Network-seeds may carry out different case studies in the same or different countries. Dash lines between cases reflect projects belonging to the same international network/organization in a same country. Seeds have been placed in the map according to their approximate location; if not possible to define (e.g., slow food movement), they are placed in the middle of the country

Data analysis

Content analysis

We used content analysis to identify the SDGs and related targets addressed by the 69 African seeds and explored the interactions established between SDGs within the seeds. Content analysis identifies patterns and helps to build valid inferences about their meaning (Riffe et al. 1998). It requires three main elements (White and Marsh 2006): (1) sampling units (identify the population and establish the basis for sampling—here the 69 African ‘Seeds of Good Anthropocenes’), (2) data collection units (the components that make up a document, here coded information available in the Seeds database, as well as phrases, figures, photos or tables containing relevant information about the initiatives in their websites and related popular and scientific articles), and (3) units of analysis (basis for analyses—the 169 SDG targets). Originally formulated as universal ambitions, these targets were, in some cases, adapted for grassroots (or local) analyses. For example, target 10.1: “by 2030, progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average” has been reformulated as achieve and sustain income growth of the poor, i.e., initiatives generating employments for vulnerable populations (see Table S1 for a more complete coding scheme of the targets). For the 69 initiatives, we checked whether they met each one of the 169 SDG targets in an iterative process of coding and re-examining as the variety of the sample increased with every new initiative revised (see Box 1 for an example, and Figure S1 for the complete coding of the seeds). Then, we measured the interactions between SDG targets built on the information about the targets being addressed “as a whole” by every single seed initiative.

Descriptive analysis, frequency and interactions between SDGs

First, we used descriptive statistics to explore how many of the targets within each goal were addressed by the 69 seeds. For example, Goal 17 is defined in the 2030 Agenda by 19 targets, of which 8 appear in our sample; while Goal 13 has 5 targets of which 4 are in our sample.

Second, to measure how often the 17 goals were addressed by the seeds, we (1) represented the percentage of seeds addressing each one of the goals; and (2) conducted a Chi squared test of the number of times a target was addressed by the seeds within every goal in relation to the number of targets per goal defined by the 2030 Agenda. For the Chi squared test, we standardized the residuals (i.e., the difference between expectation and observation) by the number of targets within each goal (see Equations S1, Equation 1). Standardizing the residuals allows us to compare the difference between observed and expected frequency of targets observed within each SDG by the total number of targets within each SDG. Using these two measures we considered the frequency of both the different goals and the range of targets addressed by the seeds (e.g., some goals may be addressed by many seeds—high frequency at the goal level—but just considering a few of their targets—low frequency at the target level).

Third, to asses the variety of the different types of SDGs in the seeds, we used Folke et al. (2016) framework to categorize the goals according to whether they fall into the ecological, social or economic dimension. According to this framework Goal 17 was defined as being a cross-cutting goal across all three domains. The frequency of each goal was calculated for each of the three domains independently. We also represented the top 10 most frequent targets. For these analyses, and the rest of analyses conducted in relation to the frequency and interactions of the SDGs, targets 1.2, 2.1, 5.1 and 7.1 (see Table S1) were taken away from the sample. These targets were considered as general targets, i.e., summarizing the main idea of their whole goal, so they were always coded as “present” when any other target from their same goal was addressed. Thus, their overrepresentation may cover up real frequency and interaction values if not excluded.

Fourth, to analyse the type of targets not addressed by the seeds, we classified them as (a) process-oriented or input targets, which seek to ensure adequate resource allocation (human, financial and community resources) and appropriate design of programs and activities, and are frequently stated at the national or international scale; (b) structural targets, which seek a fundamental change in organizations or systems to overcome institutional capacity weaknesses and challenges; and (c) outcome targets, focused on the achievement of a specific change, e.g., behaviour, knowledge, skills, status or level of functioning (SDSN 2015; GCPSE 2016; Seidman 2017).

Finally, to analyse patterns of interactions between SDGs, we used network analysis to measure the targets’ degree, i.e., the number of different targets one target is related to in the same initiative (see Box 1). Many authors have used network analyses to measure interactions among SDGs (Le Blanc 2015; Vladimirova and Le Blanc 2016; Weitz et al. 2018). In this research, as the information has been collected at the target level and then aggregated to the goal level, we used the average degree for every goal, calculated as the mean of the degree of the targets within a goal (e.g., to calculate the degree of Goal 1 we calculated the mean of the degree of Targets 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and so on; and the degree of Target 1.1, for example, is the number of times this target appear together with other different targets along the 69 seeds). This procedure is based on the idea that the target level is fundamental to achieving the goals, as target interactions across goals are the real concern when implementing any strategy (Weitz et al. 2018). Thus, the degree is considered as a measure of the likelihood of a target to be organically integrated with other targets in local social–ecological initiatives, a higher degree representing a higher likelihood. We also calculated the degree for each target, but normalized as the deviation from the expected total average degree, i.e., the mean of the degree for all the targets in the sample (see Equations S1, Equation 2).

Cluster analysis

To analyse the characteristic of the different goals in relation to how are they addressed by the locally grounded initiatives, we used average linkage method with Euclidean distances to perform a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) of the 17 SDGs. The HCA was performed for some of the frequency and interaction measures detailed in the previous section, i.e., the percentage of seeds addressing a goal, observed vs expected targets (standard residuals), and average degree of the goals. It also includes other two variables to measure interactions between targets: (1) the percentage of interactivity within a goal to explore whether the different targets within a same goal usually share the same seeds or not (see Equations S1, Equation 3); and (2) the percentage of interactivity inter-goals, as a measure of the average number of interactions of every goal with other goals in the seed initiatives (i.e., which goals are addressed by the same seeds). Consequently, goal (not target) interactions were considered in this latter variable.

Results

Incidence of the different goals and targets addressed by the seeds

Goals and targets addressed by the seeds

125 targets (out of a total of 169 targets described in the 2030 Agenda) were addressed by the 69 African seeds. The frequency of individual targets appearing in the seeds varied greatly among seeds, as some targets are addressed by many seeds (e.g., 12% of the targets appear in more than 15 seeds), while most targets only occur in a few (e.g., 52% of the targets appear in fewer than 5 seeds).

All 17 SDGs were addressed by the seeds. However, within the different goals, there was a large difference in the number of targets addressed by the seeds (Fig. 2). For instance, Goals 15 (biodiversity), 4 (education), 6 (clean water), and 7 (energy) had all their targets addressed by the seeds. In contrast, less than half of the Goal 5 (gender) targets were addressed, and it was also the goal with the least number of targets addressed by the seeds (n = 4).

Considering the frequency with which the different targets and goals were addressed by the seeds, we found Goal 4 (education) addressed by the highest number of seeds (65%) and had the highest number of targets addressed by the seeds. Goals 6 (clean water), 1 (no poverty), 2 (zero hunger), 8 (decent work & growth), 10 (reduced inequality), and their related targets, were also frequently addressed; while Goals 16 (peace & justice), 3 (health), 14 (oceans), 5 (gender), 13 (climate action), and related targets, were vaguely addressed by the seeds (Fig. 3). Goal 17 (partnership) was addressed by a high number of seeds (61%), but a low total number of targets within this goal were addressed (Fig. 3).

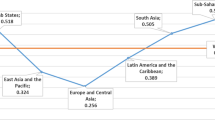

Number of times (frequency) the SDGs are addressed by the seeds, at the goal and target level. “x axis” represents the percentage of seeds initiatives addressing a goal; while “y axis” represents the standard residuals or the normalized difference between the observed and the expected targets addressed by the seeds. Negative values indicated that the observed number of targets was lower than the expected. “General targets” has been removed (see methods section)

Targets not addressed by the seeds

Of the 169 targets defined by the 2030 Agenda, 44 targets were not addressed by the seeds. These targets were characterized by requiring a national or international scope that is usually beyond the capacity of locally grounded sustainability initiatives. For example, missing targets were mainly process-oriented or input targets (n = 20) such as Target 1A (mobilization of resources from governments to implement programmes and policies to poverty eradication) or Target 9A (facilitation of international financial and technological support to infrastructure development). Unaddressed targets also included those requiring national level structural changes (n = 16) such as Target 10.6 (enhancing the representation voice for developing countries in decision-making in global international economic and financial institutions) and Target 14.6 (prohibiting some forms of fisheries subsides contributing to overfishing).

Other targets that were not addressed were primarily focused on developed countries, e.g., Target 12.1 (implementation of the 10-year framework of programmes on sustainable consumption and production, all countries taking action, with developed countries taking the lead); or because the topic was not directly related to social-ecological problems, e.g., Target 3.6 and 3A (reducing the number of deaths from road traffic accidents and tobacco consume, respectively).

The social, ecological and economic dimensions of the goals and targets addressed by the seeds

Following Folke et al. (2016)’s social–ecological classification of the SDGs, 21% of the targets addressed by the seeds belong to the ecological, 43% to the social and 28% to the economic dimension. The remaining 8% of the targets corresponded to Goal 17 (partnership; Fig. 4). When considering the ecology-related goals, Goal 15 (biodiversity) and 6 (clean water) were the most frequent (i.e., 38% of the ecology-related targets addressed by the seeds were both within Goal 15 and 6), with a high representation of target 6.3 (improving water quality by reducing pollution and eliminating dumping). Goals 14 (oceans; 13%) and 13 (climate action; 18%) were the least frequent ecology-related goals.

Percentage of targets addressed by a seed within a goal according to their ecological, social or economic dimension (based on Folke et al. (2016)). SDG17 is presented as a cross-cutting goal. Table on the right shows the top ten most frequent targets addressed by the seeds. Numbers into parenthesis show the percentage of seeds addressing the target. “General targets” has been removed (see methods section)

Of the social goals, Goal 4 (quality education) exhibited the highest frequency (27% of the social-related targets addressed by the seeds belonged to Goal 4). Target 4.7 (ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development), had the highest overall frequency across the whole set of goals, being addressed by 42% of the seeds (Fig. 4). The social-related goals that were less addressed by the seeds were Goals 16 (peace & justice; 5%), 5 (gender; 7%), 7 (energy; 7%), and 3 (health; 8%).

Of the economic goals, Goals 8 and 10 exhibited the highest frequencies (decent work and growth, 34%; and reduce inequalities, 28%). Target 8.6 (substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training) was the most frequent under Goal 8. It is closely related to the goals from the social dimension, and specifically to education. For Goal 10, the most frequent targets were 10.1 (employment generation for the poor) and 10.2 (empowerment and inclusion) (see Fig. 4 and Table S1). Goal 12 was the less frequent economic related goal (responsible consumption & production; 20%). However, Target 12.5 (reducing waste generation by prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse) had a high representation on the sample, being addressed by 32% of the seeds.

Patterns of interactions between SDGs

The degree of interaction among the targets was related to their frequencies in the sample. Overall the most frequent goals and related targets—Goals 8 (decent work & growth), 2 (zero hunger), 1 (no poverty), 6 (clean water), 10 (reduced inequalities), and 4 (education)—exhibited the highest number of co-occurence with other targets. Less frequently addressed goals exhibited the fewest number of interactions between different targets (Fig. 5).

Number of interactions among the different targets (degree). “x axis” shows the goal degree, calculated as the mean (for all the targets within a goal) of the number of interactions of one target with the others from all the 17 SDGs (n = 169). “General targets” has been removed (see methods section). “y axis” shows how the number of interactions of one target with the others deviates from the average number of interactions among targets for the whole set of targets addressed by the seeds (Total average = 55.62). Targets belonging to the goals placed on the grey area have an average number of interactions below the total average

However, we found some exceptions. For instance, Goal 11 and related targets (sustainable cities & communities) were frequently addressed by the seeds, but exhibited a low number of interactions with other targets. This is also the case for Goals 7 (energy) and 9 (industry & innovation), although the average number of interactions of their related targets was similar to the average number of interactions for all the targets addressed by the seeds (x̅=55.62). More interactive than expected were Goals 5 (gender), 12 (responsible consumption & production), and 17 (partnership). These goals had a low frequency of their targets addressed by the seeds but presented a high number of interactions.

Finally, Goals 9 (industry & innovation) and 16 (peace & justice), and Goals 14 (oceans) and 7 (clean energy) did not have any interactions, meaning that not a single initiative addressed these goals together.

Clustering the SDGs in the context of the African seeds

Six groups of goals were identified by our hierarchical clustering of the frequency variables [i.e., percentage of seeds addressing a goal and observed vs expected targets (standard residuals)] and interaction variables (i.e., average degree of goals, interactivity within the goals and interactivity among different goals; see Table S2) (Fig. 6).

The first cluster includes Goal 11 (sustainable cities & communities) alone. This reflects the particularity of this goal and its targets when implementing local initiatives. Goal 11 has a high frequency of its targets in the sample and is addressed by 41% of seeds; however, it presents a low interaction between targets within Goal 11 and across other goals. The second cluster, SDGs addressed by specific projects, consisted of goals that are addressed by few seeds and usually these seeds focus on a narrow set of targets within one specific goal. This cluster includes Goals 7 (energy) and 9 (industry & innovation). For instance, Goal 7 projects have a strong focus on fostering affordable and clean energy—especially for vulnerable populations—addressing a limited number of other different targets, e.g., solar energy micro utilities (or solutions in a box) like Solar Turtle (www.solarturtle.co.za) or Ishack (www.ishackproject.co.za). The third cluster, SDGs under-represented, includes goals poorly represented in our sample, i.e., Goals 14 (oceans), 3 (health), 13 (climate action) and 16 (peace & justice). These goals are addressed by few seeds and present a very low frequency of their targets and interactions (low degree). Group four clusters Goals 17 (partnership) and 4 (education), which are used as means of implementation for some other goals. For instance, Target 4.7—sustainable education—was the most addressed target by the seeds, as it is used as a supporter for the rest of the activities related with other goals. For example, the Nosso Mar, Nossa Vida project (https://ama-amigosdaterra.org/osol-projecto-nossa-mar-nossa-vida-bioclimate/) that aims to support fishing co-management in Mozambique through locally appropriate and sustainably financed resource management, also engages with some sustainable education activities for the achievement of its goals. Goals 17 and 4 are addressed by many seeds and their related targets interact with many different targets (very high degree) across different goals, but less so within goals 17 and 4, because there is a high variety of targets in these goals that are not necessarily related to each other. The fifth group consisted on goals mainly addressed by general or broad projects: Goals 8 (decent work & growth), 10 (reduced inequalities), 1 (no poverty), 2 (zero hunger) and 6 (clean water). These goals and related targets are addressed by the highest number of seeds and have a very high interaction with other goals and targets. They relate to projects with a broad aim definitions, that develop many activities (or programs) addressing multiple goals, e.g., Kwetu Training Centre (http://www.kwetukenya.org) addresses 41 targets from 12 different goals (including all the goals in this cluster), with the purpose of promoting mariculture and silviculture technologies to diversify the livelihood options of local communities dependent on mangrove wetlands as well as advocating for the conservation and sustainable use of mangroves in coastal communities. Cluster 6 is made of cross-cutting SDGs, and includes Goals 5 (gender), 12 (responsible consumption & production) and 15 (biodiversity). Their related targets, while presenting a low frequency in our sample, present high levels of interaction with other goals and targets. For instance, gender equality appears as a cross-cutting issue in many projects related with different topics, e.g., The Seed and Knowledge Initiative (http://www.biowatch.org.za) aims to bring together policy makers, NGOs, researchers and farmers’ organisations, in order to stimulate discussion around sustainable agricultural production and garner support for small-scale farmers practicing agro-ecological methods of crop production. In doing so, this seed specifically considers the participation of women in these meetings.

Discussion of findings

Different ways local initiatives are addressing the 2030 Agenda

The 2030 Agenda mandates the implementation of the SDGs as an indivisible whole. This emphasizes the importance of assessing interactions between SDGs when initiatives and actions are implemented (Nilsson et al. 2016; ICSU 2017; Pradhan et al. 2017; Weitz et al. 2018). However, most attention to date has been on mapping potential interactions among a smaller sub-set of SDGs, or at the national policy level. Less focus has been given to empirically analyse how ongoing local sustainability initiatives are addressing SDGs, and what interactions emerge from these implementations. While the 2030 Agenda represents a universal and homogeneous approach to the 17 goals and related targets, we have found that SDGs differ in how local initiatives engage with them. Specifically, some SDGs can be addressed by diverse local actions (e.g., education, no poverty or gender) while addressing other SDGs requires more targeted local actions (e.g., industry and innovation). Other SDGs can only be addressed in specific places (e.g., oceans) or require large-scale approaches (e.g., health). Our analysis identified 6 types of SDGs based on their relationship to our set of local African seeds: (1) cross-cutting SDGs, (2) SDGs used as means of implementation, (3) Goal 11 (sustainable cities & communities), (4) SDGs addressed by broad-scope projects, (5) SDGs addressed by specific projects, and (6) under-represented SDGs.

We found that some SDGs were cross-cutting, in the sense that they were addressed by many of the 69 African seeds, despite not being the focal agenda of those initiatives. This is the case for gender (Goal 5), biodiversity (Goal 15) and responsible consumption & production (Goal 12). The gender equality goal is especially relevant as less than half of its targets appear on the sample, and has the lowest number of targets addressed by the seeds (n = 4), but it has many interactions with other goals and targets. Weitz et al. (2018) highlight the strong positive influence that some gender related targets have for the achievement of other goals. Gender equality is often conceived narrowly in development strategies (Miller and Razavi 1995; Struckmann 2018), and this matches the pattern we see in our sample in which many of the seeds only address one or a few gender equality related targets rather than many, for example, accounting for a certain percentage of women participants in the project, giving micro-credits for fostering women entrepreneurship, creating green-business opportunities for women to work or developing business skill training programs for women.

Other SDGs were addressed by the seeds as means of implementing other goals, for example, education is used as a means to achieve many other SDGs. This pattern exists both for education (Goal 4) and for partnership for the goals (Goal 17), which is how this latter goal is defined in the 2030 Agenda. The important role played by education in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda (Vladimirova and Le Blanc 2016) is reflected in the practice of the seeds initiatives. This goal was addressed by 65% of the seeds, its related targets had the higher observed/expected ratio and the “education for sustainability” target was the most frequent target (addressed by 42% of the seeds). Using educational activities as a strategy to achieve other goals has been widely reported in the conservation and environmental education field (Jiménez et al. 2014), and its effectiveness relies of its integration within the other goals.

Goal 11, related to sustainable cities and communities, was not clustered with any other goal. Miuigan and Cooper (1988, p.191) recognize that when carrying out cluster analyses, “not all observations must be classified for an effective or useful classification. Thus, some elements can be left unclustered or incompletely clustered”. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to continue exploring which characteristics isolate Goal 11 from other targets and goals when implementing locally based initiatives. In line with this, Pereira et al. (2018a) recently developed a typology of international urban seeds that shed light on the multiple different ways urban initiatives can perform.

Our results also show a division in how the SDGs were addressed in our set of local initiatives between: (a) broad-scope projects, which have a wide definition of their objectives and usually develop many different activities or programs related with a variety of topics -and SDGs-, such as work and economic growth (Goal 8), reduced inequalities (Goal 10), no poverty (Goal 1), zero hunger (Goal 2) and clean water (Goal 6); and (b) projects with very specific objectives, focus on topics -and SDGs- such as energy (Goal 7) or industry & innovation (Goal 9). The first group of SDGs shows higher levels of interactions established between different goals and targets, which could be read as a greater support for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda, according to its explicit determination of implementing the SDGs as an “indivisible whole” (Nilsson 2017, p.3). These broad-scope projects often implement a variety of semi-independent programs to target multiple audiences and address complex problems from different approaches (e.g., Lewa Wildlife Conservancy; see Box 1). However, we hypothesise that a combination of targeted and broad-scope initiatives is necessary to address the whole integrated set of SDGs while making advances in reaching the individual targets. Furthermore, different types of initiatives are probably important to maintaining resilience in the sustainable development process through diversity and redundancy in approaches. But in this study we do not assess how effective the initiatives are at reaching their goals. The combined dynamics and effectiveness of different types of local initiatives in achieving SDGs is clearly an important area for future research.

SDGs and local initiatives: gaps, context, and method

Some of the SDGs were not well represented in our sample, i.e., oceans (Goal 14), health (Goal 3), climate action (Goal 13) and peace & justice (Goal 16). While the lack of ocean related targets is directly linked to terrestrial focus of most of the seeds in the sample; the lack of SDGs addressing health, peace and climate action might be due to the strong reliance on, or expectations of, government action in this space, or of international NGOs and other relatively large multi-lateral actors such as the UN. Similarly, Pradhan et al. (2017) analysed SDG interactions across 227 countries, and also found there was little data related to Goals 14 and 16 to analyze their interactions, which may reflect difficulties in addressing these targets at different scales. Furthermore, the low representation of the climate action goal and related targets could be due to the vague formulation of this goal in the 2030 Agenda. Climate change’s big challenges might be expected to be addressed through the achievement of other goals and measured through other sets of indicators (see, e.g., Sachs et al. 2017; Weitz et al. 2018).

The results of this study are specific to our set of seeds in Africa, and accordingly our findings are not generalizable to all local-level initiatives. However, we expect that some of the patterns we identify are likely to occur elsewhere. For example, cross-cutting SDGs and SDGs used as means of implementation may be similarly addressed by seeds from other regions. We also expect that other clusters of SDGs would be addressed by the seeds following different patterns. For example, SDGs linked to broad-scope projects—here mainly aimed at dealing with poverty and its derived conditions—may be addressed similarly across the Global South, but not in the seeds developed in the Global North where these goals would be probably less frequently addressed by local initiatives (Smith et al. 2018). Goal 11 (sustainable cities and communities) is isolated from other goals in the cases we analysed, but may be more connected in the more developed areas in the Global North or some Latin American regions, where the presence of slums is not such a widespread challenge. Some of the underrepresented goals, such as Goal 14 (oceans), may also clearly follow a different pattern in coastal areas, small islands and island nations. We hypothesise that Goal 13 (climate action) frames many sustainability initiatives in the Global North.

Finally, our analysis presents a new methodology to code and evaluate the performance of local social-ecological initiatives in addressing the SDGs using both frequency and interaction variables. While these variables have been sufficient to analyse our data, there is substantial potential to further improve the methods for measuring and exploring different SDG interactions, adapting them to the different realities and types of data. Some specific challenges are the normalization of the variables according to the number of targets per goal defined on the 2030 Agenda, the multiples ways of measuring interactions (e.g., degree (Le Blanc 2015; Weitz et al. 2018)) or distinguishing between interactions within and among SDGs (Pradhan et al. 2017), as well as the different agglomerations and disaggregations to work both at the target and goal level (Pradhan et al. 2017).

Our analysis relies on and explores how the selected set of locally grounded African initiatives understand the connections between the SDGs. While this understanding may well be reflective of the contexts at hand, the systematic analyses of interactions used here helps to shine a spotlight on where there may be glaring gaps to addressing problems (e.g., the case of gender inequalities). We believe this approach could be useful in other studies to analyse how local interventions address the SDGs and comparison among different types of local initiatives to provide new insights into alternative pathways towards sustainability.

Key future considerations for bottom-up approaches to the 2030 Agenda

The Anthropocene presents a set of interlinked grand challenges from humanity. As people address the Anthropocene challenges that they experience through local actions, governments have agreed on the SDGs as a formalised and globally harmonised set of goals to overcome these challenges. While these are framed at a global level, the initiatives and behaviours that might lead to sustainable development are enacted primarily at local, national and regional levels. We therefore ask how these on-the-ground initiatives might be related to this global sustainability agenda.

Our results show how the local initiatives (i.e., seeds) have developed different strategies to meet their objectives and bring impacts to scale. For example, some seeds have specifically focused on activism strategies for changing or braking global mainstream structures or enhancing policy coherence for sustainable development (Avelino 2011). Local Futures (https://www.localfutures.org/) for example, works to correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in agricultural markets (target 2B), and Pure Earth (http://www.pureearth.org/) contributes to early warning and management of national and global health risks (target 3D). Both initiatives are configured as big international alliances or organizations, which may have a greater impact when pushing institutions toward structural changes. Other initiatives are more involved in networks that form polycentric structures, i.e., creating systems characterized by multiple units at differing scales, where each unit has sufficient independence to make rules within a specific domain (Ostrom 2010). Through local, regional or international partnerships, most of the seeds have established arrangements and joint projects with actors at multiple levels (Galaz et al. 2012). An example of such partnerships—polycentric structures—can be seen through the case of Lewa Wildlife Conservancy (http://www.lewa.org/), which maintains a strong relation with the Kenian enforcement authorities (such as police and national wildlife service) to fight cases of poaching, cattle rustling, road banditry and inter-tribal conflicts in the conservancy and surrounding areas.

Furthermore, the agency of the seeds in enabling or creating the envisioned sustainable development is shaped within the polycentric structures and linkages between institutions at different levels, governance hierarchies and socio-economic-political priorities. These contexts can influence which SDG targets are addressed by the seeds, and the depth in how cross-cutting SDGs and their targets are considered and strategized for implementation. As presented, some initiatives have a specialised focus, others a broader scope, some present stronger contextual specificity, while others are more generalist. Together, they form an integrated ecosystem of initiatives that shape and are shaped by the evolving landscape of (sustainable) development. However, our analysis is of the activities developed by the local initiatives and how they related to specific SDGs. We did not identify whether the initiatives are successful in achieving selected SDG targets or, more broadly, changing what sustainable development is. Analysing the impact of seeds would require a broad and systematic monitoring of the set of initiatives that enacts the 2030 Agenda, and an effort to map how these activities address the complex, evolving and intertwined structure of sustainable development issues (Galaz et al. 2012). While responding to these questions go beyond the scope of this research, issues of governance, power and agency must be contemplated in future analysis regarding the implementation of the SDGs by locally based initiatives.

Concluding remarks

Current attempts to analyse interactions among SDGs have focused on potential interactions at the national policy level rather than empirically analysing how ongoing local initiatives are addressing them. This article explores how bottom-up approaches are contributing to the 2030 Agenda. We have made a first attempt to define and illustrate the different ways SDGs can be addressed by local initiatives, by taking into account their specific features, measured in terms of incidence (which goals are more likely to be addressed) and degree of interaction between and among targets and goals. We found that local initiatives broadly address these SDGs, but that SDGs have six different types of relationships to local initiatives. Efforts to monitor the success on implementing the SDGs in local contexts should be reinforced (Satterthwaite 2016, 2018), and consider these and others different patterns initiatives follow to address the goals.

Additionally, our results suggest that achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda will require diversity and alignment of bottom-up and top-down approaches. On the one hand, development agencies should identify, recognise and support the creation of polycentric systems around a variety of seeds that are contributing to SDGs achievement in different ways, and target work on those SDGs left behind, or those that require higher level action. On the other hand, for new sustainability approaches to emerge and grow, the seeds should continue with an experimental and creative work by strategically engaging with SDGs in multiple different ways and adapting their networked polycentric organizational structures to the interlinked and evolving challenges they address.

Finally, within this ecosystem of initiatives, it is often easy to overlook the “subjects” of development. A complementary area of future research would be to critically examine how the people—individuals, families and communities—are engaged in the process of development, and how different perspectives, knowledge systems and agencies can be integrated into the diversity of strategies and visions for sustainable development.

References

Allen C, Metternicht G, Wiedmann T (2019) Prioritising SDG targets: assessing baselines, gaps and interlinkages. Sustain Sci 14:421–438

Avelino F (2011) Power in transition. Empowering Discourses on Sustainability Transitions. Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam

Bennett EM, Solan M, Biggs R et al (2016) Bright spots: seeds of a good Anthropocene. Front Ecol Environ 14:441–448

Berkes F, Folke C (1998) Linking social and ecological systems: management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. Cambridge University Press, New York

Boas I, Biermann F, Kanie N (2016) Cross-sectoral strategies in global sustainability governance: towards a nexus approach. Int Environ Agreem Polit Law Econ 16:449–464

Collste D, Pedercini M, Cornell SE (2017) Policy coherence to achieve the SDGs: using integrated simulation models to assess effective policies. Sustain Sci 12:921–931

Folke C, Biggs R, Norström AV et al (2016) Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol Soc 21(3):41. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08748-210341

Galaz V, Crona B, Österblom H et al (2012) Polycentric systems and interacting planetary boundaries—emerging governance of climate change-ocean acidification-marine biodiversity. Ecol Econ 81:21–32

GCPSE (2016) SDG implementation framework. Effective public service for SDG implementation. http://www.localizingthesdgs.org/ (29 June 2018)

Geels FW (2002) Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res Policy 31:1257–1274

Geels FW, Schot J (2007) Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res Policy 36:399–417

Gunderson LH, Holling CS (2002) Panarchy: understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Island Press, Washington

ICSU (2017) A guide to SDG interactions: from science to implementation. International Council for Science, Paris

Jaramillo F, Desormeaux A, Hedlund J et al (2019) Priorities and interactions of sustainable development goals (SDGs) with focus on wetlands. Water 11:619

Jiménez A, Iniesta-Arandia I, Muñoz-Santos M et al (2014) Typology of public outreach for biodiversity conservation projects in Spain. Conserv Biol 28:829–840

Le Blanc D (2015) Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Sustain Dev 23:176–187

Miller C, Razavi S (1995) From WID to GAD: conceptual shifts in the women and development discourse. UNRISD Occasional Paper, No. 1. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), Geneva

Miuigan GW, Cooper MC (1988) A study of standardizaction of variables in cluster analysis. J Classif 204:181–204

Moore M-L, Tjornbo O, Enfors E et al (2014) Studying the complexity of change: toward an analytical framework for understanding deliberate social-ecological transformations. Ecol Soc 19(4):54. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06966-190454

Nilsson M (2017) Important interactions among the Sustainable Development Goals under review at the High-Level Political Forum 2017. SEI Working paper 2017-06. Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm

Nilsson M, Griggs D, Visback M (2016) Map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 534:320–322

Nilsson M, Chisholm E, Griggs D et al (2018) Mapping interactions between the sustainable development goals: lessons learned and ways forward. Sustain Sci 13:1489–1503

Norström AV, Dannenberg A, McCarney G et al (2014) Three necessary conditions for establishing effective sustainable development goals in the Anthropocene. Ecol Soc 19(3):8

Olsson P, Gunderson LH, Carpenter SR et al (2006) Shooting the rapids: navigating transition to adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01595-110118

Ostrom E (2010) Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Glob Environ Chang 20:550–557

Pereira LM, Bennett E, Biggs R et al (2018a) Seeds of the future in the present: exploring pathways for navigating towards “Good” Anthropocenes. In: Elmqvist T, Bai X, Frantzeskaki N et al (eds) Urban planet. knowledge towards sustainable cities. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pereira LM, Hichert T, Hamann M et al (2018b) Using futures methods to create transformative spaces: visions of a good Anthropocene in Southern Africa. Ecol Soc 23(1):19. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09907-230119

Pradhan P, Costa L, Rybski D et al (2017) A systematic study of sustainable development goal (SDG) interactions earth’s future. Earth’s Futur 5:1169–1179

Raworth K (2012) A safe and just space for humanity. Oxfam Discussion Paper, Oxford

Raworth K (2017) Doughnut economics. Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing, Hartford

Reed J, van Vianen J, Sunderland T (2015) From global complexity to local reality: aligning implementation pathways for the sustainable development goals and landscape approaches, vol 129. Center for International Forestry Research, Bogor

Riffe D, Lacy S, Fico FG (1998) Analyzing media messages: using quantitative content analysis in research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey

Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K et al (2009) A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461:472–475

Sachs J, Schmidt-Traub G, Kroll C et al (2017) SDG index and dashboards report 2017, New York

Satterthwaite D (2016) Where are the local indicators for the SDGs? In: IIED blog post. https://www.iied.org/where-are-local-indicators-for-sdgs. (20 June 2019)

Satterthwaite D (2018) Who can implement the sustainable development goals in urban areas? In: Elmqvist T, Bai X, Frantzeskaki N et al (eds) Urban planet knowledge towards sustainable cities. University Printing House, Cambridge, Cambridge, pp 408–4011

SDSN (2015) Indicators and a monitoring framework for the sustainable development goals. launching a data revolution. http://indicators.report/ (29 June 2018)

Searchinger T, Heimlich RA, Houghton F, Dong A, Elobeid J, Fabiosa J, Tokgoz S, Hayes D, Yu T-H (2008) Use of U.S. croplands for biofuels increases greenhouse gases through emissions from land-use change. Science 319(5867):1238–1240

Seidman G (2017) Does SDG 3 have an adequate theory of change for improving health systems performance? J Glob Health 7:1–7

Smith MS, Cook C, Sokona Y et al (2018) Advancing sustainability science for the SDGs. Sustain Sci 13:1483–1487

Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockström J et al (2015) Planetary boundaries: guiding changing planet. Science 347:736–746

Stephens A, Lewis ED, Reddy S (2018) Towards an inclusive systemic evaluation for the SDGs: gender equality, environments and marginalized voices (GEMs). Evaluation 24:220–236

Struckmann C (2018) A postcolonial feminist critique of the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development: a South African application. Agenda 32:12–24

United Nations (2012) The future we want. Outcome document of the United Nations conference on sustainable development

United Nations (2015a) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1

United Nations (2015b) The Millennium Development Goals Report

Vladimirova K, Le Blanc D (2016) Exploring links between education and sustainable development goals through the lens of UN flagship reports. Sustain Dev 24:254–271

Weitz N, Carlsen H, Nilsson M, Skånberg K (2018) Towards systemic and contextual priority setting for implementing the 2030 Agenda. Sustain Sci 13:531–548

White MD, Marsh EE (2006) Content analysis: a flexible methodology. Libr Trends 55:22–45

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript for their insightful comments and suggestions for strengthening the paper. We also would like to thank Sonja Radosavljevic for her help with the equations. This is a contribution to the Guidance for Resilience in the Anthropocene: Investments for Development (GRAID) Programme led by the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University, and funded by the Swedish Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), and is part of the ‘Seeds of a Good Anthropocene’ Project (https://goodanthropocenes.net/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handled by Riyanti Djalante, United Nations University, Japan.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiménez-Aceituno, A., Peterson, G.D., Norström, A.V. et al. Local lens for SDG implementation: lessons from bottom-up approaches in Africa. Sustain Sci 15, 729–743 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00746-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00746-0