Abstract

Background

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services launched the 4-year Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative (CPC Classic) in 2012 and its 5-year successor, CPC Plus (CPC+), in 2017 to test whether improving primary care delivery in five areas—and providing practices with financial and technical support—reduced spending and improved quality. This is the first study to examine long-term effects of a primary care practice transformation model.

Objective

To test whether long-term primary care transformation—the 4-year CPC Classic and the first 2 years of its successor, CPC+—reduced hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and spending over 6 years.

Design

We used a difference-in-differences analysis to compare outcomes for beneficiaries attributed to CPC Classic practices with outcomes for beneficiaries attributed to comparison practices during the year before and 6 years after CPC Classic began.

Participants

The study involved 565,674 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to 502 CPC Classic practices and 1,165,284 beneficiaries attributed to 908 comparison practices, with similar beneficiary-, practice-, and market-level characteristics as the CPC Classic practices.

Interventions

The interventions required primary care practices to improve 5 care areas and supported their transformation with substantially enhanced payment, data feedback, and learning support and, for CPC+, added health information technology support.

Main Measures

Hospitalizations (all-cause), ED visits (outpatient and total), and Medicare Part A and B expenditures.

Key Results

Relative to comparison practices, beneficiaries in intervention practices experienced slower growth in hospitalizations—3.1% less in year 5 and 3.5% less in year 6 (P < 0.01) and roughly 2% (P < 0.1) slower growth each year in total ED visits during years 3 through 6. Medicare Part A and B expenditures (excluding care management fees) did not change appreciably.

Conclusions

The emergence of favorable effects on hospitalizations in years 5 and 6 suggests primary care transformation takes time to translate into lower hospitalizations. Longer tests of models are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Payers around the country are testing the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) and similar models and increasingly paying for health care through alternative payment models that reward quality and value.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 Researchers and practitioners have warned that it takes time to transform care and shift patient outcomes,1,11,12,13 but there have been no long-term models (running for greater than five years) to assess whether the generally minimal changes that have been documented in outcomes such as emergency department visits and hospitalizations 1 actually improve with longer interventions. Against this backdrop, it is important to understand how longer tests of these models affect health care spending and utilization.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the 4-year multipayer Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative (CPC Classic) in October 2012; CPC Classic tested whether it was possible to reduce spending and improve quality by requiring primary care practices to improve care delivery in five areas: (1) access to and continuity of care, (2) planned care for preventive and chronic needs, (3) risk-stratified care management, (4) engagement of patients and their caregivers, and (5) coordination of care with patients’ other care providers. The model provided substantially enhanced payment, including a $20 per beneficiary per month (PBPM) care management fee (CMF) from CMS in the first 2 years, and a $15 PBPM CMF in the last two years, as well as data feedback and learning support. Across the country, 502 practices participated in CPC Classic. Over the 4-year initiative, CPC Classic reduced the growth in hospitalizations by about 1.6% and both total and outpatient ED visits by 2% among CPC Classic practices relative to comparison practices, but it did not appreciably alter Medicare Part A and B expenditures. A favorable 1.7% (P = 0.06) reduction in hospitalizations emerged in year 1, but the estimated effect was slightly smaller and not quite statistically significant in years 2 through 4. The favorable impacts on ED visits became more pronounced over time and were statistically significant (P < 0.03) in the third and fourth intervention years.2,14,15

Building on the lessons of CPC Classic and other advanced primary care models, in January 2017, CMS launched the 5-year CPC+ model, which is the largest and most ambitious primary care payment and delivery reform ever tested in the USA.3 Table 1 shows the main features of the 2 models were similar, with the notable differences being CPC+ (1) was larger in size, (2) increased emphasis on aspects of comprehensiveness, including behavioral health integration and assessing and addressing patients’ social support needs, (3) allowed simultaneous participation in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (SSP), and (4) for the more advanced care transformation track: (a) added health information technology support, (b) provided substantially higher enhanced payments and progressively larger alternative to fee-for-service (FFS) payments, and (c) required some more advanced care delivery approaches. CMS offered all CPC Classic practices participation in CPC+ if they met basic eligibility criteria after CPC Classic ended, and 85% began participating in CPC+ when it started in 2017, with 83% of those participating in the more advanced care transformation track.

This study takes advantage of these unusually long combined models to examine the longer-term effects of primary care transformation on expenditures and service use for Medicare FFS beneficiaries. We examine effects over 6 years—the 4 years of CPC Classic, reported earlier,2,14,15 and the 2 years after, which for most practices included 2 years of participation in CPC+.3 We hypothesized that favorable effects with primary care transformation would emerge or remain the same over time.

METHODS

Evaluation Design

To measure the effects of primary care transformation on service use and spending, we followed the CPC Classic initial design (as reported earlier14,15) that compared changes in outcomes from the year before CPC Classic began (baseline period) to the 6-year period after it began (intervention period), between Medicare FFS beneficiaries served by intervention practices (defined as those that began CPC Classic and were still participating during the second quarter) and those served by matched comparison practices. Table 1 shows the time period of this analysis. We focused on Medicare FFS beneficiaries because their claims data are timely, accurate, and available through CMS. We used propensity score matching to ensure pre-intervention similarity between intervention and comparison practices across beneficiary, practice, and market characteristics. Matching variables included beneficiaries’ characteristics (such as age, sex, HCC scores, and prior expenditures and service use); practice-level characteristics (such as meaningful use of electronic health records, number of clinicians, and percentage of clinicians with a primary care specialty); and characteristics of the practice’s market (such as mean county income). We selected as many as 5 comparison practices for each CPC Classic practice. (For details on matching methods, see Section 3 in the supplemental appendix in Dale et al. [2016]. 14 Results from tests examining the sensitivity of our analyses to the definition of the comparison group and differential changes between the treatment and comparison group over time (for example, in sample composition) for the four years of CPC Classic were similar to the main analysis. For details on these tests and results, see Chapter 8 of the CPC Classic fourth annual evaluation report2).

Medicare FFS beneficiaries were attributed quarterly to CPC and comparison practices that delivered the largest share of their primary care visits during a 2-year look-back period. We then used an intent-to-treat (ITT) design to assign beneficiaries to practices; that is, once we had attributed beneficiaries to a practice (intervention or comparison) at any time during the intervention period, they remained in the analysis sample as long as they met the eligibility criteria (alive and enrolled in Medicare Part A and Part B with Medicare as the primary payer and not in a health maintenance organization). The appendix explains the attribution and ITT design in detail.

Outcomes

We constructed 4 main outcomes from Medicare claims and enrollment data: (1) Medicare Part A and Part B expenditures excluding enhanced payments made for CPC Classic or CPC+; (2) hospitalizations; (3) outpatient emergency department (ED) visits; and (4) total ED visits. We also examined impacts on expenditures by service category: (1) inpatient, (2) outpatient, (3) physician, (4) home health, (5) hospice, (6) skilled nursing facility, and (7) durable medical equipment.

Statistical Analysis

We implemented a difference-in-differences model that compares the mean change in outcomes from the year before the start of CPC Classic to the 6 years after between 2 groups: (1) beneficiaries served by the CPC Classic practices and (2) beneficiaries served by comparison practices. We used (1) linear regressions for Medicare Part A and Part B expenditures and (2) zero-inflated negative binomial regressions for hospitalizations, outpatient ED visits, and overall ED visits to account for a large percentage of zeroes. The regressions controlled for beneficiary, practice, and market characteristics observed at baseline to net out observable preexisting baseline differences between CPC Classic and comparison beneficiaries that remained after propensity score matching and to increase the precision of the estimates. Estimated standard errors accounted for beneficiary outcomes clustered at the practice level and for weighting. The overall weights were equal to the product of 2 separate weights that accounted for (1) the share of the year for which the beneficiary’s data were observed and (2) the matching (which adjusts for the number of comparison practices matched to each CPC practice). We performed all statistical analyses with Stata software (version 15.1). We provide P values for all estimates and consider P value < 0.10 to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Practices Included in the Study Sample

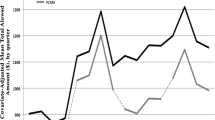

The analysis included 497 practices participating at the end of CPC Classic’s first quarter and 908 similar comparison practices. The intervention and comparison practices had similar practice characteristics during baseline (Table 1 in Dale et al. [2016]14), and similar trajectories of Medicare expenditures, hospitalizations, outpatient ED visits, and total ED visits in the 2 years before CPC Classic began (Fig. 1).

Quarterly trends in unadjusted average Medicare expenditures, hospitalizations, outpatient ED visits, and total ED visits in the 2 years before CPC Classic began. Source: Analyses of Medicare claims data from October 2008 through December 2012. Notes: The figure shows actual, unadjusted average expenditures, hospitalizations, outpatient ED visits, and total ED visits in the 2 years before CPC Classic began.

Beneficiaries Included in the Study Sample

The original sample included all beneficiaries attributed to CPC Classic (565,674) and their comparison practices (1,165,284), from the baseline period until the fourth intervention year (October 2012 to December 2016). For the 2 years after CPC Classic ended (January 2017 to December 2018), we followed the beneficiaries already assigned in the fourth-year analysis sample into their fifth and sixth years with the same intervention or comparison status as in CPC Classic. Tables 2 and 3 show that the intervention and comparison groups were similar on the baseline beneficiary characteristics and outcomes, respectively.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates for Main Outcomes

Effects on Hospitalizations

Over 6 years of primary care transformation, we found that relative to comparison practices, beneficiaries in intervention practices experienced slower growth in hospitalizations (−2.2%, P = 0.02) compared to baseline. The estimates were smaller in the first 4 years (−1.7% or less) and were generally not statistically significant. The favorable effects increased to 9 fewer hospitalizations per 1000 beneficiaries (−3.1%, P = 0.01) in year 5, and 11 fewer hospitalizations per 1000 beneficiaries (−3.5%, P < 0.01) in year 6 (Table 4 and Fig. 2).

This figure shows the estimated effects on expenditures and service use, by year. The estimate of the effect, denoted by a separate triangle for each intervention year, is equal to the difference in mean outcomes between attributed Medicare FFS beneficiaries in the intervention and comparison group practices in any year since CPC Classic began, minus the average difference between the two groups during the baseline period. The estimates are regression adjusted to control for baseline differences in beneficiary and practice characteristics between the intervention and comparison groups. The dashed lines indicate the 90% confidence interval. Source: Medicare claims data for October 2011 through December 2018. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; FFS, fee-for-service: Y, year.

Effects on ED Visits

Relative to comparison practices, beneficiaries in intervention practices experienced slower growth in total ED visits (−2.0%, P = 0.01) over 6 years of primary care transformation. The favorable effects became sizeable and statistically significant starting in year 3—increasing gradually from 15 fewer visits per 1000 beneficiaries (−2.0%, P = 0.01) in year 3 to 20 fewer visits per 1000 beneficiaries (−2.6%, P = 0.01) in year 6 (Table 4 and Fig. 2).

Similarly, beneficiaries in intervention practices experienced slower growth in outpatient ED visits (−1.8%, P = 0.07) relative to comparison practices. Like the total ED visits, the estimates became sizeable and statistically significant starting from year 3. The favorable effects were 13 fewer visits per 1000 beneficiaries (−2.5%, P = 0.01) in year 3, 11 fewer visits per 1000 beneficiaries (−2.2%, P = 0.05) in year 4, and 12 fewer visits per 1000 beneficiaries (−2.2%, P = 0.09) in year 5. The favorable estimate of 8 fewer visits per 1000 beneficiaries (−1.6%, P = 0.24) in year 6 was not statistically significant (Table 4 and Fig. 2).

Effects on Overall Expenditures

Over the 6 years of primary care transformation, intervention and comparison practices had similar Medicare Part A and B FFS expenditures excluding additional payments from CPC Classic and CPC+ (Table 4 and Fig. 2).

The results were robust when using alternative regression specifications (such as models that trimmed high-cost cases) and we did not find any evidence for variation in impacts by practice type for the four years of CPC Classic (see chapter 8 of the CPC Classic fourth annual evaluation report).2

Difference-in-Differences Estimates for Expenditures by Service Category

Over the 6 years of primary care transformation, the cumulative and yearly estimates indicate that the interventions had no statistically significant effects on Medicare inpatient, physician, home health, or durable medical equipment expenditures for FFS beneficiaries. Despite the slower growth in hospitalizations, the effect of the interventions on inpatient expenditures was not statistically significant. Although the interventions led to slightly lower outpatient and skilled nursing facility expenditures over the 6-year period, they also led to increased physician and hospice expenditures (Appendix Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Results from this analysis provide the first estimates of long-term effects of primary care transformation on expenditures and service use outcomes. We examined 6 years of expenditures and utilization data, combining 4 years of CPC Classic, followed by the first 2 years of CPC+.

We found that the intervention had a favorable reduction of 2% on hospitalizations over the full 6-year period, which was driven by annual estimates that emerged in the fifth year (−3.1%) and persisted into the sixth year (−3.5%). In addition, the favorable reductions in total ED visits and outpatient ED visits (approximately −2% each) that were observed in years 3 and 4 of the CPC Classic intervention also persisted in the fifth and sixth follow-up years.

The temporal pattern of effects on ED visits and hospitalizations is consistent with our expectations about how primary care transformation works—outcomes like ED visits could be easier to improve in the short run, which would explain the quick emergence of favorable effects, whereas a longer time horizon may be needed to see improvements in outcomes like hospitalizations. Because most CPC Classic practices (85%) joined CPC+ in 2017 (and continued participating in 2018), these favorable effects reflect the 4 years of CPC Classic and the 2 years of CPC+. We cannot determine how much of the effects is attributable to the lagged effects of CPC Classic versus the additional years of support through CPC+. Although CPC+ did not lead to significant favorable improvement in outcomes (particularly hospitalizations) in its first 2 years across the full sample of participating practices (including those that were new to CPC+ as well as those that participated previously in CPC Classic),3 CPC+ may have provided important support to continue the work begun in CPC Classic for the CPC Classic practices that joined.

Although the favorable effects on hospitalizations in the fifth and sixth years are promising, they did not translate to a discernable impact on Medicare Part A and Part B expenditures. There are two potential explanations. First, despite the strong favorable effects on hospitalizations in years 5 and 6, the magnitude of the corresponding favorable effects with inpatient expenditures in these years was small (and not statistically significant). This suggests that the avoided hospitalizations were relatively less severe and thus less costly. Second, there were offsetting estimated increases in physician and hospice expenditures.

Finally, even the impacts on hospitalizations and emergency department use that we do observe are modest in size. It is possible that impacts might be larger if primary care practices had stronger incentives or if there were incentives for other providers (including hospitals and specialists) who care for the same patients. Also, beneficiaries were not rewarded for taking better care of themselves or seeking higher-value providers or services. Finally, comparison practices’ outcomes may have improved due to other efforts to transform primary care (for example, through the increase in penalties for high readmission rates); this may have made it difficult for the intervention practices to generate reductions in savings or service use relative to the comparison practices.

This study has two main limitations. First, because the design is not experimental, unobservable differences between the intervention and comparison practices could bias the estimated effects. For example, Daw and Hatfield show that regression to the mean can lead to bias in studies with comparison group designs (like this one) that match on pre-period outcomes; they also point out that this issue is especially problematic when the difference in out comes between potential comparisons and selected comparisons is large.16 However, the average outcome values in the group of potential comparison practices (pre-matching) and selected comparison practices (post-matching) in this study were small,14 suggesting that regression to the mean is not likely to substantially bias these results.

Second, findings from CPC Classic and the start of the CPC+ model, with the unique set of practices and patients, may not generalize to other payers, primary care models, or participants with different eligibility requirements, model rules, and supports. Future research should observe these practices for the final 3 years of CPC+ and test long-term effects for other primary care transformation models.

CONCLUSION

This study’s findings have important implications for how payers and policymakers should test and assess primary care reform over longer periods. The results suggest that primary care transformation may reduce ED visits quickly, that it could take 5 years of robust support to reduce hospitalizations, and that reducing total health care spending may require longer or new approaches. More research is needed to follow these practices over the remaining 3 years of CPC+ and to examine other primary care transformation approaches to see if similar temporal patterns are found.

References

Peikes D, Taylor EF, O’Malley AS, Rich EC. The changing landscape of primary care: effects of the ACA and other efforts over the past decade. Health Aff. 2020;39(3):421–28.

Peikes D, Anglin G, Dale S, et al. Evaluation of the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative: fourth annual report. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica; 2018.

Anglin G, Peikes D, Peterson D, et al. Independent Evaluation of Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+): second annual report. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica; 2020.

RTI International; Urban Institute; National Academy for State Health Policy. Evaluation of the Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Practice (MAPCP) demonstration: final report. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2017.

Kahn KL, Timbie JW, Friedberg MW, et al. Evaluation of CMS’s Federally Qualified Health Care (FQHC) Advanced Primary Care Practice (APCP) demonstration: final report. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2017.

Kimmey L, Anderson M, Cheh V, et al. Evaluation of the Independence at Home demonstration: an examination of the first four years. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica; 2019.

Peterson G, Blue L, Moreno L, et al. Evaluation of Health Care Innovation Awards (HCIA): primary care redesign programs: third annual report. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica; 2017.

RTI International. State Innovation Models (SIM) initiative evaluation: model test year five annual report. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2018.

Abraham MR, McGann P. Contribution of the Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative in advancing the movement to value-based care. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(suppl 1):S6–8.

Edwards ST, Bitton A, Hong J, Landon BE. Patient-centered medical home initiatives expanded in 2009–13: providers, patients, and payment incentives increased. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(10):1823–31.

Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Primary care practice transformation is hard work: insights from a 15-year developmental program of research. Med Care. 2011;49(suppl): S28-35.

McNellis RJ, Genevro JL, Meyers DS. Lessons learned from the study of primary care transformation. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(suppl 1):S1-5.

Nutting PA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Jaen CR, Stewart EE, Stange KC. Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):254–60.

Dale SB, Ghosh A, Peikes DN, et al. Two-year costs and quality in the Comprehensive Primary Care initiative. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2345–56; Supplementary Appendix available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/suppl/10.1056/NEJMsa1414953/suppl_file/nejmsa1414953_appendix.pdf. Accesses 20 Apr 2021

Peikes D, Dale S, Ghosh A, et al. The Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative: effects on spending, quality, patients, and physicians. Health Aff. 2018;37(6):890–99.

Daw, Jamie R., and Laura A. Hatfield. “Matching and regression to the mean in difference-in-differences analysis.” Health Services Research 53.6 (2018): 4138-4156.)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ CPC Classic initiative program team and its contractors for sharing information and data. The authors also acknowledge the significant contributions to this study that were provided by Xiaofan Sun, Swaati Bangalore, Mattan Alalouf, Neetu Jain, Mike Rudacille, and Laura Blue at Mathematica.

Data Availability Statements

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to contract requirements with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Funding

This study is funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under contracts HHSM-500-2010-00026I/HHSM-500-T0006 and HHSM-500-2014-00034I/HHSM-500-T0010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Document Ethics/Institutional Review Board Approval

The New England Institutional Review Board (IRB) granted CPC Classic an IRB exemption on the basis of the federal common rule (section 45 CFR 46.101[b][5]), because the purpose of the study was to evaluate a public benefit program. The CMS program team designed and administered the execution of the model for the initiative. The manuscript was approved for submission through a standard CMS communications clearance process.

Conflict of Interest

Ning Fu, Pragya Singh, Stacy Dale, Sean Orzol, Deborah Peikes, Arkadipta Ghosh, and Randall Brown conducted the submitted analysis under contracts with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; they and Timothy J. Day have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer

The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation of the manuscript. The manuscript was approved for submission through a standard CMS communications clearance process.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 117 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, N., Singh, P., Dale, S. et al. Long-Term Effects of the Comprehensive Primary Care Model on Health Care Spending and Utilization. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 1713–1721 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06952-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06952-w