Abstract

Background

Intensive primary care programs aim to coordinate care for patients with medical, behavioral, and social complexity, but little is known about their impact on patient experience when implemented in a medical home.

Objective

Determine how augmenting the VA’s medical home (Patient Aligned Care Team, PACT) with a PACT-Intensive Management (PIM) program influences patient experiences with care coordination, access, provider relationships, and satisfaction.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of patient survey data from a five-site randomized quality improvement study.

Participants

Two thousand five hundred sixty-six Veterans with hospitalization risk scores ≥ 90th percentile and recent acute care.

Intervention

PIM offered patients intensive care coordination, including home visits, accompaniment to specialists, acute care follow-up, and case management from a team staffed by primary care providers, social workers, psychologists, nurses, and/or other support staff.

Main Measures

Patient-reported experiences with care coordination (e.g., health goal assessment, test and appointment follow-up, Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC)), access to healthcare services, provider relationships, and satisfaction.

Key Results

Seven hundred fifty-nine PIM and 768 PACT patients responded to the survey (response rate 60%). Patients randomized to PIM were more likely than those in PACT to report that they were asked about their health goals (AOR = 1.26; P = 0.046) and that they have a VA provider whom they trust (AOR = 1.35; P = 0.005). PIM patients also had higher mean (SD) PACIC scores compared with PACT patients (2.91 (1.31) vs. 2.75 (1.25), respectively; P = 0.022) and were more likely to report 10 out of 10 on satisfaction with primary care (AOR = 1.25; P = 0.048). However, other effects on coordination, access, and satisfaction did not achieve statistical significance.

Conclusions

Augmenting VA’s patient-centered medical home with intensive primary care had a modestly positive influence on high-risk patients’ experiences with care coordination and provider relationships, but did not have a significant impact on most patient-reported access and satisfaction measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

In response to rising healthcare costs, many healthcare systems have started implementing intensive primary care programs for high-need patients with medical, social, and behavioral complexity.1,2,3,4,5 These programs typically include proactive care coordination and case management to address medical issues, care fragmentation, care transitions, and other healthcare navigation challenges.6

Evidence of intensive primary care’s impact on healthcare utilization patterns is mixed.4, 5, 7, 8 A recent systematic review of 18 studies by Edwards et al. found that most intensive primary care programs had no impact on mortality or emergency department use, and the effectiveness in reducing hospitalizations varied.8 Some of the most promising findings around acute care use have emerged from programs for older adults that have reported reductions in hospitalizations and/or length of stay.9,10,11

The effects of intensive primary care on quality of care and quality of life are more promising. In a 2009 Institute of Medicine review, Boult et al. found that comprehensive care for older adults frequently had positive effects for quality of life.12 For example, the GRACE model was associated with improvements in quality indicators for general healthcare and geriatric conditions, and improvements in vitality, social function, and mental health.13 In a pilot Veterans Affairs (VA) intensive primary care program, enrollment was associated with significantly more visits with an assigned primary care physician, higher rates of advance directive completion, and higher rates of hospice referral near end of life.14, 15

Fewer studies have examined the impact of intensive primary care on patient experience. A recent evaluation of Comprehensive Primary Care among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries found that there was no appreciable improvement in beneficiary experience compared to individuals in matched practices.16 A limited number of randomized controlled trials of intensive primary care suggest potential benefits for patient satisfaction with specific elements of care, such as transitions17 and access to telephone advice.18 However, there have been few rigorously designed trials that have included a comprehensive assessment of the experiences of patients receiving intensive management compared to those receiving usual primary care.

To address the gap in evidence about patient experiences with intensive primary care, we conducted a survey of patients in a multi-site randomized quality improvement trial of intensive primary care in the VA healthcare system. Previously, we found that access to the VA program increased use of primary care, social work, and mental health services, with no increase in total costs.19 In this study, we hypothesized that the program positively influenced patient perceptions of their care coordination, and related experience measures such as satisfaction and perceived access.

METHODS

This study examines the results of a survey conducted as part of an evaluation of a five-site VA intensive primary care demonstration project. One of the largest integrated healthcare systems in the USA, the VA provides care to more than eight million eligible Veterans. Since 2010, VA primary care has been delivered by Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), which are structured based on a patient-centered medical home model.20 PACT teamlets include a primary care provider, nurse, clinical associate, and administrative associate, and are supported by social work, pharmacy, and behavioral health services.

While PACT implementation improved patient satisfaction and reduced acute care utilization,21 VA leadership recognized that additional resources were required to meet the needs of Veterans with particularly complex and high-risk profiles. In 2014, VA’s Office of Primary Care implemented the PACT-Intensive Management (PIM) Demonstration Program to augment PACT services for Veterans at high risk for hospitalization (i.e., individuals whose risk of 90-day hospitalization was ≥ 90th percentile based on the VA’s Care Assessment Need (CAN) score)22 and who had experienced a hospitalization or emergency department (ED) visit in the previous 6 months.

The PIM Demonstration Program has been described previously.19, 23 Building on effective intensive outpatient interventions such as GRACE,13 a VA Intensive Management PACT (ImPACT) pilot,14, 15, 24, 25 and lessons learned from other early programs,4, 5, 7 the five PIM programs incorporated features such as regular interdisciplinary team meetings, medication management, home visits, mental health/substance use assessment and support, health coaching, and intensive social work case management. In addition, the teams engaged in a number of specific activities to coordinate care within VA and across VA and other settings (Table 1).

Design of PIM Evaluation

The PIM Demonstration Program and associated utilization and cost evaluations were designed to support VA leadership priorities and were therefore designated as quality improvement (QI) by VA’s Office of Research and Development and Office of Research Oversight (#NCT03100526).19 Because the QI evaluation was restricted to analyses of data collected for PIM or PACT clinical care,23 we obtained approval for an additional patient survey from Stanford University’s Institutional Review Board and VA Palo Alto’s Research and Development Committee.

Survey Sample

The survey sample was drawn from a list of high-risk Veterans who were randomized to PIM or usual PACT care between August 2014 and December 2015 at the five VA facilities with PIM Demonstration Programs. The survey was conducted from June 3, 2016, to December 16, 2016. Veterans were eligible to participate in the survey if they had a valid mailing address or telephone number and could answer survey questions. Veterans unable to respond to the printed or telephone survey had the option of designating a caregiver to complete the survey on their behalf. Of the 2566 potential participants, 38 were not eligible (i.e., deceased or did not have a valid mailing address or telephone number). Of the remaining sample, 1527 (60%) completed the survey; 737 individuals could not be contacted by mail or telephone; and 264 individuals opted out of the mailed survey or refused telephone follow-up (Appendix 1).

Survey Procedures

All eligible Veterans were mailed a survey packet containing the survey, a cover letter, an information sheet describing the study’s risks and benefits, a one-time $2 pre-incentive, and an opt-out form. Non-respondents received a second packet, a reminder postcard, then a third packet, and finally a postcard informing the recipient that he or she would be contacted by telephone. A completed survey indicated informed consent to participate. Respondents were mailed a $10 check in appreciation of their time.

Survey Measures

Survey measures were derived from widely used patient surveys,26,27,28 and validated measures of care coordination from the literature.29, 30 Patient experiences with care coordination were assessed using questions from VA’s Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP),26 adapted from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS).27 Patients were asked whether in the last 6 months someone had talked to them about their specific goals for their health and things that make it hard for them to take care of their health, whether someone had asked them about their medications, and whether they had received reminders about tests, treatment, or appointments between clinic visits. Responses were analyzed using standard SHEP procedures (i.e., percentage that responded “yes”). Patients were also asked whether their VA primary care providers seemed informed about the care they got from specialists (analyzed using top-box scoring based on percentage that responded “always”) and whether they had a VA healthcare provider who helped “coordinate care from different doctors and services” (analyzed using top-box scoring based on percentage that responded, “agree strongly”).

We also examined two validated measures that broadly consider patient experiences with their care and care coordination. The first was the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC),29 a six-item measure (analyzed as a composite score) that asks about care coordination activities related to chronic illnesses, such as contact after a visit and discussion about how specialists are contributing to treatment. The second was the Health Care Hassles Scale,30 which queries patients about diverse challenges such as insufficient information about treatment options, difficulties refilling medications, and perceptions that concerns were overlooked (responses range from 0 (not a problem) to 4 (very big problem), and the scale is analyzed as a composite score that ranges from 0 to 60).

Access and relationships with providers were assessed by asking whether patients agreed with the statements “I got the service I needed” and “it was easy to get what I needed”26 and with the adapted questions, “I have a VA healthcare provider who I can contact when I have questions about my care,” “I have a VA healthcare provider who I trust,” and “I have a VA healthcare provider who respects me.” Responses were analyzed using standard SHEP procedure: the percentage who responded “agree strongly.”

Satisfaction with VA care (including overall care, and primary care, mental healthcare, and social services) was assessed using questions adapted from the 2013 Customer Satisfaction Index.28 Respondents rated their experiences on a scale of 1 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied). We examined the proportion that rated their satisfaction 10 out of 10, and the mean satisfaction ratings after converting ratings to a 0–100 scale.

Finally, because only a subset of randomized patients participated in PIM, survey respondents were queried whether they were currently or previously enrolled in PIM. Those who endorsed enrollment were asked about their satisfaction with the program, and whether the PIM team was responsive to their health concerns, helped them get VA care and services that they needed, improved their overall care with VA, and helped them meet their goals.

Covariates assessed through the survey included social support (evaluated using the Medical Outcomes Survey questions about tangible social support),31 loneliness and isolation (measured using the R-UCLA Loneliness Scale),32 health literacy (measured using Chew et al.’s single item),33 functional status (assessed using the National Institute of Health’s PROMIS Short Form Physical Function 4a measure),34 education, and income. Other covariates obtained from VA’s national Corporate Data Warehouse included age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, and clinical complexity (as measured by the average risk for 90-day hospitalization during the 6 months prior to randomization, based on the VA’s CAN score).22

Statistical Analyses

We used chi-square and t tests to compare sociodemographic and clinical characteristics among all survey respondents and non-respondents. For patients randomized to PIM vs. PACT, we compared administrative data-based sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and survey-based measures of health literacy, social support, education, and income. We describe responses for each outcome measure for three groups: patients randomized to PIM, patients randomized to PACT, and the subset of patients randomized to PIM who reported that they were currently or previously enrolled in the program.

In primary intention-to-treat analyses, we conducted logistic regression models to examine whether randomization to PIM was associated with differences in patient experiences. Separate models were conducted for each outcome within the domains of care coordination, provider relationships, access, and satisfaction. To account for potential respondent bias, we used logistic regression to calculate the probability of response for PIM and PACT patients, then used inverse probability weighting to account for low response in each group. Models were run using PROC SURVEY LOGISTIC in SAS. In sensitivity analyses, we included site fixed effects and adjusted models for demographic and clinical covariates that differed between PIM and PACT patients with a P value < 0.2. All covariates were missing at rates < 5%. In order to determine whether PIM effects varied by certain patient characteristics, we conducted secondary analyses to assess the first-order interaction term for model covariates that were significantly associated with study outcomes. All tests were two-sided and conducted at the 0.05 level of significance, with an odds ratio of 1.5 constituting a small effect based on Cohen’s conventions for effect size.35, 36

RESULTS

Survey respondents were older than non-respondents (mean (SD) age of 64.4 (11.5) vs. 61.8 (13.5); P < 0.001) and were more likely to be married (34.1% vs. 28.7%; P = 0.005), but were similar in terms of sex, race/ethnicity, and clinical complexity (Appendix 2). There were no significant differences between PIM (N = 759) and PACT (N = 768) survey respondents across any sociodemographic or clinical characteristics (Table 2).

Patient Perceptions of Care Coordination

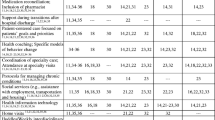

Patients randomized to PIM were more likely than those in PACT to report that someone talked to them about their health goals (73.1% vs. 68.4%; AOR (95% CI) = 1.26 (1.00, 1.59)) and barriers to taking care of their health (60.4% vs. 54.8%; AOR (95% CI) = 1.26 (1.02, 1.56)) (Fig. 1). PIM patients also had higher mean (SD) scores for the PACIC chronic illness care scale (2.91 (1.31) in PIM vs. 2.75 (1.25) in PACT; P = 0.022) but not for the mean (SD) Health Care Hassles scale (9.87 (11.83) in PIM vs. 10.17 (11.24) in PACT; P = 0.61) (see Appendix 3 for results for individual items). Other differences in coordination measures were not statistically significant (Fig. 1, Table 3).

Experiences of patients randomly allocated to PIM (N = 759) vs. PACT (N = 768). Superscript letter “a” indicates percentage of patients who responded “yes” when asked about receipt of services in the past 6 months. Superscript letter “b” indicates percentage of patients who responded that they “always” experience this element in their care. Superscript letter “c” indicates percentage of patients who responded that they “agree strongly” that they received or experienced the specified care.

Provider Relationships and Access

Patients randomized to PIM were more likely than patients in PACT to strongly agree that they have a VA healthcare provider whom they trust (60.5% vs. 53.1%; AOR (95% CI) = 1.35 (1.10, 1.66)). There were no other statistically significant differences in perceptions of relationships or access, including receipt of needed services, ease of getting needed services, and having an accessible VA provider when questions about care arise (Fig. 1, Table 3).

Satisfaction

PIM patients were more likely than PACT patients to report 10 out of 10 on satisfaction with primary care (36.5% vs. 31.7%; AOR (95% CI) = 1.25 (1.05, 1.47)) (Table 3). There were no significant differences in PIM vs. PACT patients’ mean satisfaction ratings of their overall VA care, or component primary care, mental healthcare, or social services (Appendix 3).

PIM Program Participant Assessment of PIM Services

Among the 759 patients who were randomized to PIM, 732 responded to a question about enrollment, and 281 (38%) reported that they were currently or previously enrolled in the program (Appendix 1). Among the self-reported enrolled patients, 46% (124/269) reported 10 out of 10 on satisfaction with PIM, and a majority reported that the PIM team was responsive to their health concerns (80%, 219/273), helped them get VA care and services that they need (82%, 224/273), improved their overall care with VA (72%, 195/270), and helped them meet their health goals (70%, 190/270).

Sensitivity Analyses and Interaction Terms

Sensitivity analyses with site fixed effects and adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical factors that differed between PIM and PACT patients with a P value < 0.2 (i.e., age and functional status) yielded similar results (Appendix 4). Secondary analyses assessed the first-order interaction term for tangible social support and greater functional status (which were associated with positive patient experience outcomes in most models), but the interaction terms for each of these covariates with the intervention were nonsignificant for the majority of outcomes (results not shown). Finally, we examined the responses of the 38% of PIM patients who reported current or previous PIM enrollment. Appendix 5 illustrates that the responses of these patients were slightly higher than the responses for the overall population randomized to PIM for 9 out of 11 measures of care coordination, relationships with providers, and access.

DISCUSSION

This study represents one of the first comprehensive assessments comparing the care experiences of patients in intensive primary care with those of patients receiving usual care in a patient-centered medical home. Previously, we found that the PIM program offered high-need Veterans more primary care, social work, and mental health services, with no increase in total costs.19 Survey findings suggest that the program may have influenced some patients’ experiences with patient-centered care and chronic illness care, and increased the number of patients who reported having a trusted provider, but did not influence satisfaction, perceived access, or most measures of care coordination.

Taken as a whole, these findings suggest that the program had a modest effect in domains that were related to relationship-building (i.e., having a trusted provider) and patient-centeredness (i.e., assessing patient’s health goals), as well as perceived chronic illness care. Trusting relationships have been described as the basis for engaging patients in case management and primary care, particularly when attempting to engage patients with complex medical, social, and behavioral needs.37 Furthermore, relationships are at the core of primary care, so this finding suggests that augmenting a medical home with an intensive management program may help fulfill the promise or primary care. In fact, analyses of satisfaction suggest that the program improved patients’ experiences with primary care, but not with other services. Improving primary care processes could potentially have positive long-term consequences, including changes in health behaviors and clinical outcomes.38

One explanation for why the program did not have a greater effect on care coordination experiences is that the VA’s medical home already addresses basic coordination needs such as medication review and providing reminders between visits, so the greatest opportunity for improvement is in offering patients more time with an attentive team that can conduct in-depth assessments of their goals, priorities, barriers, and challenges.

It is notable that only 38% of patients who were randomized to PIM reported that they were enrolled in the program. Previous evaluations have documented that over half of those randomized to PIM were identified as not needing the intervention, were offered the intervention but declined, or received fewer than three encounters.19 Other patients may not have distinguished between PIM and their usual PACT care, which already included a number of ancillary services. Among the patients who reported receiving PIM services, nearly half reported 10 out of 10 on satisfaction with the program, and a majority felt that the program was responsive to their concerns and helped them meet their health goals and obtain needed services. While these patients represent a minority of the intention-to-treat population, their responses appear to drive the differences between outcomes for the randomized populations (Appendix 5).

Our study was limited to five VA primary care sites that chose to participate in an intensive primary care demonstration program. VA facility-level data for four SHEP questions in the survey indicate that three of the five sites had ratings that were at least 5% higher than the national average for three of the four questions. As a result, findings may not be generalizable to VA (or non-VA) sites with poor patient experience ratings at baseline, where a resource-intensive program could potentially have a greater impact. In addition, there were 17 tests included in our primary analyses, each of which was examined in two sensitivity analyses. Overall, the findings for trust and patient-centered care outcomes were robust even in the most conservative models; however, results that were of borderline significance in the main analyses, such as patient experiences with care coordination logistics, should be interpreted with caution.

To our knowledge, this is the first multi-site randomized trial to investigate the effects of intensive primary care on such a broad array of patient experience outcomes. Our findings suggest that augmenting a medical home with intensive primary care can increase the number of high-need patients who report having a provider whom they trust, and may improve patient-centered care coordination and perceived chronic illness care. While the overall effects on population-level patient experiences were modest, these domains are aligned with current VA priorities and may have a long-term impact on clinical outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.

References

McWilliams JM. Cost Containment and the Tale of Care Coordination. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2218–20.

Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Pumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for High-Need, High-Cost Patients -- An Urgent Priority. N Engl J Med 2016;375:909–11.

Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program?: The Commonwealth Fund; 2014.

McCarthy D, Ryan J, Klein S. Models of care for high-need, high-cost patients: An evidence synthesis: The Commonwealth Fund; 2015.

Bodenheimer T. Strategies to Reduce Costs and Improve Care for High-Utilizing Medicaid Patients: Reflections on Pioneering Programs: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.; 2013.

National Academy of Medicine (Long PAM, Milstein A, Anderson G, Lewis Apton K, Lund Dahlberg M, Whicher D, editors). Effective Care for High-Need Patients: Opportunities for Improving Outcomes, Value, and Health. Washington, D.C. 2017.

Hong C, Siegel A, Ferris T. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? : Issue Brief, Commonwealth Fund; 2014:1–19.

Edwards ST, Peterson K, Chan B, Anderson J, Helfand M. Effectivess of intensive primary care interventions: A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:1377–86.

Meret-Hanke LA. Effects of the Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly on hospital use. Gerontologist 2011;51:774–85.

Bayliss EA, McQuillan DB, Ellis JL, et al. Using Electronic Health Record Data to Measure Care Quality for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Medical Conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:1839–44.

Beland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, et al. A system of integrated care for older persons with disabilities in Canada: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:367–73.

Boult C, Green AF, Boult LB, Pacala JT, Snyder C, Leff B. Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: evidence for the Institute of Medicine's "Retooling for an Aging America" report. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:2328–37.

Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Buttar AB, Clark DO, Frank KI. Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE): a new model of primary care for low-income seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1136–41.

Hummel DL, Hill C, Shaw JG, Slightam C, Asch SM, Zulman DM. Nurse Practitioner-led intensive outpatient team: Effects on end-of-life care (Brief Report). J Nurse Pract 2017.

Wu FM, Slightam CA, Wong AC, Asch SM, Zulman DM. Intensive Outpatient Program Effects on High-need Patients' Access, Continuity, Coordination, and Engagement. Med Care 2018;56:19–24.

Peikes D, Dale S, Ghosh A, et al. The Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative: Effects On Spending, Quality, Patients, And Physicians. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:890–9.

Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:675–84.

Boult C, Leff B, Boyd CM, et al. A matched-pair cluster-randomized trial of guided care for high-risk older patients. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:612–21.

Yoon J, Chang E, Rubenstein LV, et al. Impact of Primary Care Intensive Management on High-Risk Veterans’ Costs and Utilization: A Randomized Quality Improvement Trial. Ann Intern Med 2018.

Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care 2013;19:e263–72.

Nelson KM, Helfrich C, Sun H, et al. Implementation of the patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration: associations with patient satisfaction, quality of care, staff burnout, and hospital and emergency department use. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1350–8.

Wang L, Porter B, Maynard C, et al. Predicting risk of hospitalization or death among patients receiving primary care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care 2013;51:368–73.

Chang ET, Zulman DM, Asch SM, et al. An operations-partnered evaluation of care redesign for high-risk patients in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA): Study protocol for the PACT Intensive Management (PIM) randomized quality improvement evaluation. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;69:65–75.

Zulman DM, Ezeji-Okoye SC, Shaw JG, et al. Partnered Research in Healthcare Delivery Redesign for High-Need, High-Cost Patients: Development and Feasibility of an Intensive Management Patient-Aligned Care Team (ImPACT). J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:861–9.

Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Ezeji-Okoye SC, et al. Effect of an Intensive Outpatient Program to Augment Primary Care for High-Need Veterans Affairs Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:166–75.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients: Ambulatory Care 2013. Washington DC: Office of Quality and Performance; 2013.

Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research. CAHPS Clinician & Group Surveys: 12-Month Survey 2.0. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research,; 2011.

American Customer Satisfaction Index: 2013 Customer Satisfaction Outpatient Survey: Veterans Health Administration; 2014.

Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med Care 2005;43:436–44.

Parchman ML, Noel PH, Lee S. Primary care attributes, health care system hassles, and chronic illness. Med Care 2005;43:1123–9.

Moser A, Stuck AE, Silliman RA, Ganz PA, Clough-Gorr KM. The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:1107–16.

Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies Res Aging.2004;26:655–72.

Chew L, Griffin J, Partin M, et al. Validation of Screening Questions for Limited Health Literacy in a Large VA Outpatient Population. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:561–6.

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). 2012. (Accessed 10/4/12, at http://nihpromis.org/.)

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, second edition. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Chen H, Cohen P, Chen S. How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Commun Stat Simul Comput 2010;39:860–4.

O'Brien CW, Breland JY, Slightam C, Nevedal A, Zulman DM. Engaging high-risk patients in intensive care coordination programs: The Engagement through CARInG Framework. Transl Behav Med 2018;8:351–6.

Starfield BH, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83:456–502.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the contributions of PIM team members Neha Pathak and Kathy Hedrick, who provided critical feedback during survey development. We would also like to acknowledge the five PIM teams that partnered in this study, led by Brook Watts, Jessica Eng, Parag Dalsania, Jeff Jackson, and Deborah Henry. PIM Executive Committee members Gordon Schectman, Kathy Corrigan, Tim Dresselhaus, Angela Denietolis, David Atkins, Carrie Patton, Belinda Black, and Susan Kirsh were critical to the PIM Demonstration Program design and execution. In addition, the following contributors served as scientific or technical advisors, supported data analysis, or provided ethics consultation: Elvira Jimenez, Shoutzu Lin, Suwei Wang, Liberty Greene, Cindie Slightam, Angel Park, Emily Wong, Alexis Huynh, Martin Lee, Michael Baiochi, Alyssa Simon, and Jill Darling.

Funding

The PACT-Intensive Demonstration Program and National Evaluation Center were supported by VA’s Office of Primary Care Services (XVA 65-54). Evaluation of survey data was supported by VA’s HSR&D office (FOP 16-181).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Because the QI evaluation was restricted to analyses of data collected for PIM or PACT clinical care,23 we obtained approval for an additional patient survey from Stanford University’s Institutional Review Board and VA Palo Alto’s Research and Development Committee. A completed survey indicated informed consent to participate.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 87 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zulman, D.M., Chang, E.T., Wong, A. et al. Effects of Intensive Primary Care on High-Need Patient Experiences: Survey Findings from a Veterans Affairs Randomized Quality Improvement Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 34 (Suppl 1), 75–81 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04965-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04965-0