Abstract

Objective

This research aimed to understand the experiences of patients transitioning from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) by eliciting views from patients and hospital and skilled nursing facility staff.

Design

We conducted semi-structured interviews with hospital and skilled nursing facility staff and skilled nursing facility patients and their family members in an attempt to understand transitions between hospital and SNF. These interviews focused on all aspects of the discharge planning and nursing facility placement processes including who is involved, how decisions are made, patients’ experiences, hospital-SNF communication, and the presence of programs to improve the transition process.

Participants

Participants were 138 staff in 16 hospitals and 25 SNFs in 8 markets across the country, and 98 newly admitted, previously community-dwelling SNF patients and/or their family members in five of those markets.

Approach

Interviews were qualitatively analyzed to identify overarching themes.

Key Results

Patients reported they felt rushed in making their SNF decisions, did not feel they were appropriately prepared for the hospital-SNF transition or educated about their post-acute needs, and experienced transitions that felt chaotic, with complications they associated with timing and medications. Hospital and SNF staff expressed similar opinions, stating that transitions were rushed, there were problems with the timing of the discharge, with information transfer and medication reconciliation, and that patients were not appropriately prepared for the transition. Staff at some facilities reported programs designed to address these problems, but the efficacy of these programs is unknown.

Conclusions

Results indicate problematic transitions stemming from insufficient care coordination and failure to appropriately prepare patients and their family members. Previous research suggests that problematic or hurried transitions from hospital to SNF are associated with medication errors and unnecessary rehospitalizations. Interventions to improve transitions from hospital to SNF that include a focus on patients and families are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Following a hospital stay, 20% of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries are admitted to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) for post-acute care (PAC). Medicare covers the first 100 days of SNF care after an inpatient hospital stay of at least 3 days, and this care costs Medicare 29.8 billion dollars in 2015.1 There are often problems with transitions from hospital to SNF. Research has found that approximately 20% of patients discharged from hospital to SNF are readmitted to the hospital within 30 days,2,3 and two-thirds of rehospitalizations from SNF may be preventable.4

In an attempt to improve patient outcomes, the Affordable Care Act incorporated multiple provisions that require hospitals to be more accountable for PAC services and outcomes, including financial penalties for rehospitalizations.5,6 As a result, various attempts have been made to improve hospital-SNF transitions, many of which focus primarily on improving hospital-SNF communications,7,8 or on improving the quality of SNFs to which hospitals discharge through network development.9,10 However, assessments of hospital-SNF transitions from the point of view of the clinicians, families, and patients involved are lacking.

In contrast, an evidence base exists around transitions from hospital to home; hospitals commonly implement programs designed to improve outcomes for patients transitioning home. Unlike efforts to improve transitions from hospitals to SNFs, these interventions often actively include patients and their families.11,12,13 Such interventions commonly use the Coleman Care Transitions Program,14 the Transitional Care Model,15 or ProjectRED (Re-Engineered Discharge),16 and might include helping patients and caregivers identify their own goals, home visits, or follow-up calls with patients post-discharge, or the use of transition coaches who train patients and their families on PAC skills. The lack of such patient-focused initiatives in the transition from hospital to SNF may be due in part to their complexity: whereas hospital-home initiatives are able to directly engage patients in both the hospital and home, hospital-SNF initiatives would require engaging multiple institutions: hospitals and SNFs. It might also be that the lack of patient-focused hospital-SNF transitions programs may be exacerbated by the informal and insufficient communications between hospital and SNF that often omit or distort vital patient information.17

This research was part of a larger project which aimed to examine relationships between hospitals and SNFs, including programs to reduce rehospitalizations and improve post-acute transitions, how patient information is communicated, and how patients experience transitions from hospitals to SNFs. This paper focuses primarily on the patient experience during the hospital-SNF transition, gathering insights from patients as well as hospital and skilled nursing facility staff.

METHODS

Hospital and SNF Staff Interviews

Design and Sample

This inductive qualitative content analysis was conducted in two phases. First, case studies included 138 interviews with staff of 16 hospitals and 25 SNFs in eight markets across the country. These markets varied based on region of the country, county size, Medicare Advantage penetration rates, and the absence or presence of functioning accountable care organizations.

Procedures

Two hospitals in each of the eight markets were selected based on their readmission rates (one with a low readmission rate, one with a higher rate). We then chose three SNFs to which the two hospitals discharged patients. It is important to note that the two hospitals in each market may discharge to the same SNFs. Of the 138 semi-structured staff interviews, 64 were conducted with hospital staff (21 hospitalists, 23 vice presidents of strategy or chief medical officers, and 20 discharge planners), and 74 were conducted with SNF staff (24 administrators, 24 directors of nursing, and 26 admissions coordinators). For a visual representation of the split of participants by market, hospital, and SNF, see Table 1.

Interview protocols were designed to examine relationships between hospitals and SNFs. Participants were asked about the information that is communicated during the hospital discharge, the roles of different staff, the existence of programs to improve hospital-SNF transitions, the perceived efficacy of these programs, and participants’ understanding of patients’ experiences. Relevant questions from these protocols are included in Appendix A (online). Interviews took place in participants’ offices and lasted approximately 40 min each.

Analysis

Interviews were qualitatively analyzed to identify overarching concepts and themes.18,19,20,21 We created a preliminary coding scheme based on the questions asked in our interview protocols, then adjusted the schemes iteratively; codes were added or modified when new material emerged from interviews.

Initially, all research team members read the interviews from the first two markets and individually coded each transcript. In subsequent team meetings, team members discussed and refined the coding scheme and associated code definitions according to how well the codes fit the transcript data, discussed perceptions of preliminary patterns or potential themes in the data, and reconciled interpretations of the first coded transcripts. The final coding scheme for staff interviews is included in Appendix C (online). Following completion of transcripts in the first two markets, to streamline the process, the team was divided into two sub-teams of two members each, with each team member coding the transcripts individually, then meeting to reconcile the codes and discuss potential themes. Membership in these sub-teams rotated to ensure that analytic decisions were developed independently of the other team; the full team met biweekly to discuss emerging themes.

Patient/Family Member Interviews

Design and Sample

Following completion of staff interviews, we selected five of the previous eight markets that best represented the variation of the selection criteria to revisit, and within each market, we re-recruited three SNFs (two in the smallest market), within which to interview SNF patients and/or their informal family caregivers. A total of 98 interviews were conducted with SNF patients and/or their family members.

Procedures

We recruited patients who had lived in the community prior to their hospitalization and were newly admitted to SNF from the hospital. Through pilot testing, we determined that an appropriate number of patient interviews per SNF would be 7 or 8 because these interviews could be conducted over the course of 1 day and would likely reach saturation. In order to recruit participants, the interviewer first consulted with SNF admissions coordinators to schedule a 1-day site visit. The admissions coordinator then generated a list of potential participants, with the goal of 7 or 8 patients per facility. On the day of the visit, the admissions coordinator provided the interviewer with the list of potential participants, all of whom were deemed by SNF staff to be capable of providing informed consent and who were informed about the study by SNF staff. Selection criteria included the ability to provide informed consent, presence in the SNF for PAC following a recent hospitalization, and having previously lived in the community. The interviewer then individually visited and recruited each participant. On those occasions when the patient was being visited by family members, they were also asked to participate in the interview. The interviewer described the study and its goals, and participants signed a consent form that was approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board.

Interviews were designed to characterize patients’ and their families’ experiences during the discharge planning and SNF placement process. Participants were asked to describe their role in SNF selection and if and how they were presented with alternative choices as well as whether anyone else was involved in the decision. They were also asked about the involvement of the hospital discharge planner, including the type of information that individual provided. Sample questions from this interview protocol are included in Appendix B (online). Interviews took place in patients’ rooms, lasting about 30 min, and participants were compensated $25 for their time. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed for data analysis.

Analysis

For interviews with patients, two members of the research team each read all transcripts from the first market and individually coded each transcript. In subsequent meetings, the team discussed and refined the coding scheme and coding definitions, discussed perceptions of preliminary patterns or themes in the data, and reconciled the first coded transcripts. The final coding scheme for patient interviews is included in Appendix D (online). Following coding of the first market, the two coders each coded the same three interviews in order to determine inter-rater reliability. Once inter-rater reliability was ensured (greater than 90% agreement), the two coders each coded half the remaining interviews individually, again meeting weekly.

Overall Analysis and Research Team

During analysis of both staff and patient interviews, comprehensive audit trails were retained recording team decisions, including code selection and definition and discussion of emerging themes.19,22,23,24,25 For additional information on how themes were yielded from the interview protocol and coding scheme, see Appendix E (online), which presents the themes addressed in the “Results” section, as well as example interview questions and coding scheme categories that were associated with these themes. Coded data were entered into the qualitative software package NVivo.

Reflexivity is an important part of qualitative research and requires that investigators continuously reflect on the research and their roles in conducting and reporting it. Our research team was interdisciplinary and included health services researchers from a variety of backgrounds. It included five PhDs and one MD, and included a geriatrician, cultural anthropologist, a political scientist, and a gerontologist, with levels of experience ranging from new junior faculty to highly senior investigators. All members of the research team participated in most aspects of the research, including analysis of the data.

RESULTS

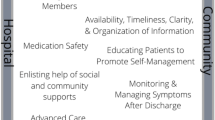

The first phase of this study included 138 interviews with staff from 16 hospitals and 25 SNFs. Table 2 includes characteristics of these hospitals and SNFs. The second phase included 98 interviews with patients in 14 of those SNFs. Table 3 includes characteristics and diagnoses/reasons for hospitalization of patient participants. Results from patients’ perspectives indicate four problematic aspects of hospital-SNF transitions: patients said they were rushed in making their SNF decisions, did not feel like they were appropriately prepared for the hospital-SNF transition or educated about their post-acute needs, and experienced transitions that were chaotic, including problems with timing and medications. Hospital and SNF staff expressed similar opinions, noting that transitions were rushed, there were problems with the timing of the discharge and information transfer and medication reconciliation, and patients were not appropriately prepared for the transition. Staff at some facilities reported programs designed to address these problems. See Table 4 for a visual presentation of these themes. Example quotes for each of these themes appear below, and additional quotes are included in Appendix F (online).

Rushed Decision Making

Patients reported that they were rushed to make discharge decisions. As a patient in the Northeast said:

They wanted to move me out the same day. And so I had to decide so that they could go forward to see if they could get a bed. (Site 4, SNF 2, Interview 8)

Staff at both SNFs and hospitals also reported time constraints that resulted in rushed hospital-SNF transitions, which in some cases were associated with rehospitalizations. As one SNF administrator in the South said:

I think the discharge planners are told, get somebody out, and I think sometimes they’re discharged too early. And they’re saying, ‘This person doesn’t have any insurance days left. They need to go.’ Well they’re not ready to go, and they send them over here, and we have to send them back the next day.... Things are conflicting. It’s one arm is saying, ‘Get them out now. The insurance is running out.’ The other is saying, ‘Well don’t let them back in.’ And they should have stayed. (Site 7, SNF 2, Interview 1)

Patients Not Educated About Post-Acute Needs

In addition to saying they felt rushed, many patients said they were not included in care coordination efforts and were not educated about needed follow-up to their hospital discharge. One family member from the Northwest described the experience of her family member:

I’ve had a number of surgeries where I just go home. And that’s always, they go over that sheet with you, the discharge sheet. That says what the follow-up is, you know, the follow-up care at home, and here’s your follow-up appointment. But I just didn’t even think about that when we came here, because nobody gave us those papers and went over them with us at the hospital! They just gave ‘em to the driver. The driver gave ‘em to the nurses’ station. He was busy getting settled in here. And so that was definitely a missed setup. (Site 3, SNF 3, Interview 5)

Patients also expressed that they would have appreciated greater inclusion. One patient from the Northwest stated:

I think I would have enjoyed knowing a little bit more about the professionalism of the [SNF] staff, but because I’ve been here before I don’t think they thought I needed that information. (Site 3, SNF 2, Interview 5)

Staff echoed these concerns, describing that patients are often not prepared for the transition from hospital to SNF. A SNF administrator from the Midwest put it:

I think we struggle as an industry, ensuring that our patients have an awareness of what’s happening with them. I think hospital systems are not consistently reviewing their medications with them upon discharge. The patients often come to us not understanding the changes in the medication that had been made and how does that impact what they took when they were at home, and what does that mean when they’re here. (Site 3, SNF 3, Interview 3)

Problematic Timing of Discharges

Patients and family members also reported problems that they experienced with regard to the timing of their hospital discharge and SNF admission. A family member from the Midwest described the confusion associated with arriving at the SNF on a Friday night:

Because we arrived on a Friday evening going into the weekend... The first time she was here…it was earlier in the day and during a weekday and so communication was good and I felt like everybody knew what was going on. Not so much this time... I think that they got a copy of the discharge summary and it was incorrect and then…I just had to try to coordinate that and so…not everything was ironed out until Monday, so I still feel like some things kind of felt like jumbled. I would never, ever do a transfer again on a Friday night after 5:00. (Site 1, SNF 2, Interview 3)

SNF staff said they perceived that admissions from the hospital were often coming late in the day and on weekends, and reported associated difficulties. An administrator from the Midwest said:

Yeah, but like on Friday we had thirteen admissions so you know going either into a holiday or a weekend you’re gonna get the same-days…so Friday night, you know, we’re all here until 7:00 trying to calm it down because I’ve got five families that thought they were gonna be in the hospital through the weekend who all of a sudden are here panicked. (Site 4, SNF 1, Interview 1)

Medication Reconciliation Problems

Another area in which patients reported problems related to the hospital-SNF transition was with regard to medications. Patients and family members discussed long waits to receive critical medications upon arrival in the SNF. A patient from the Northeast described waiting to receive transplant medications:

I’ve come here three or four times and I don’t get my meds for 24 hours and I’m on transplant medicine. And it’s not their fault here because when I get here they get my med list then they have to order them from the pharmacy. They should call here and they should have my meds when I get here. (Site 4, SNF 1, Interview 2)

Staff also reported that there are problems with medication reconciliation, as well as delays for patients to receive necessary medications. An administrator from the Midwest discussed such concerns:

Inaccurate information from the hospital to here has been a big issue where families and residents and patients get mad because they come in with an allergy to a medication that they don’t have or they discontinue the med reconciliation between their doctor and then being admitted and then they think they come here with a medication that they were never on. Med reconciliation is terrible. (Site 4, SNF 2, Interview 1)

Taking this issue a step further, SNF staff also reported that hospitals sometimes left out patient information that would have been relevant when SNFs were deciding whether to accept an admission. In other cases, SNF participants maintained that hospitals had provided inaccurate information to ensure SNF placement. A director of nursing in the Northwest described receiving inaccurate patient information:

A lot of times I’ve noticed that we’ll approve a patient, and then they’ll go in and change the meds. And then they’re on medications that we don’t use or they’re on a very expensive medication and so, you know, it is a business. We have to have some kind of income for us to get paid, but sometimes when they do that it does put us in a situation of where we’re negative, so we’re not making any money on that patient. (Site 5, SNF 4, Interview 2)

Programs to Improve These Problems

In response to these problems, some staff discussed initiatives that attempted to redesign the transition process, such as programs to improve medication reconciliation and medication delivery. A director of nursing in the Midwest described one such program:

We don’t need to order medications from the pharmacy because we have [Product Name]. It’s like a big [medication dispenser] in the hospital. Each machine holds up to 170 different medications, and we have two machines - one for long-term care, one for [PAC]. All you need to do if you have orders and scripts for controlled medications, just fax it to the pharmacy and they will release all the meds in ten, fifteen minutes. They don’t have to wait for pain medication especially. [Before] with pain medication we had to wait...between two and four hours for meds to be delivered. (Site 3, SNF 1, Interview 1)

Other initiatives staff mentioned focused on improving the quality and completeness of the patient information SNFs receive from hospitals. A discharge planner from the South described a system of inviting SNF staff into the hospital to assess patients:

We have a tool that we use when we know a patient needs a SNF. We basically bid it out through our care management software... So that kind of invites them to come and assess the patient and because some SNFs, they want to make sure they have the competencies in their own staffing to meet the needs of the more medically complex patients. (Site 7, Hospital 1, Interview 3)

Staff members said that other programs were developed to better prepare patients about what to expect during the hospital-SNF transition process. An admissions coordinator in the Northwest described its SNF’s program:

We always try to have a manager meet and greet and take them to the room, and then we actually have a new patient orientation list that we go through to explain the therapy process and what to expect during their stay here and so forth... When you go from a hospital setting to a skilled setting your staffing ratio is different, the care team is different, and so we like to meet with the patient and the family right away to let them know. (Site 5, SNF 4, Interview 3)

Still, other initiatives aimed to improve the transition process by making adjustments to staffing to better ensure coordination of care, according to some staff members. A hospital Vice President of Strategy from the Northeast said:

I put an admissions coordinator in each [SNF], so when someone is going to come into the SNF they’re having dialogues between the hospital about the transportation, about the needs of the individual, are there behaviors…to try to make it a smoother landing. (Site 6, Hospital 2, Interview 1)

DISCUSSION

Results from these interviews indicate that patients generally reported feeling rushed while making SNF decisions, did not feel engaged in care coordination, and experienced troubling transitions overall. Hospital and SNF staff echoed these concerns, citing problems with rushed transitions and poor timing, inappropriate or inaccurate transfer of information, and dealing with patients who were not prepared to transition. In a few facilities, staff reported programs designed to address these problems, which seemed to work well from the perspective of the hospitals and SNFs adopting them. However, the impact of such programs on patients’ experiences is unknown. Our findings were consistent across eight markets, 16 hospitals, and 25 SNFs and the results reveal significant problems in the transition experience from hospital to SNF. Hospital staff did not seem to appropriately prepare patients for their hospital discharge and SNF transition and SNFs were not adequately equipped to handle transitions, despite the fact that hospitals are at least partially accountable for the PAC their patients receive due to rehospitalization penalties.5,6

It appears that a major component linking problems with the hospital-SNF transition is a failure to include patients and their family members in the care coordination process. Prominent messages we heard include that patients are not given adequate notice that they will be going to a SNF, their discharge plans are not thoroughly communicated with them, and they experience delays in the discharge and in the medications they receive. Overall, findings from this study indicate inadequate communication and preparedness, both with regard to communication with patients and families, and communication between hospital and SNF staff. Many hospitals are currently working to improve these aspects of communication with SNFs,7 and have reported positive outcomes such as reductions in rehospitalizations.26,27 Nonetheless, programs addressing medication reconciliation across settings of acute and post-acute care are not prevalent, which is consistent with our study and the research literature which suggests that medication discrepancies are widely prevalent.28 Efforts to improve the hospital-SNF transition should attempt to include the patient and family member, consistent with how similar efforts address the hospital-home transition.11,12,13 Ideally, these efforts to include patients and family members should begin with post-acute setting selection, since research suggests that patients may prioritize aspects of their own care experience over standardized quality measures.29 Our study indicates that patients and family members would like to be involved in the PAC transition process; indeed, they described not being included as “a missed setup,” and expressed confusion about their own medications, not knowing about appointments, that they did not know what to ask hospital and SNF staff, and that they “would have enjoyed knowing a little bit more.”

Future research might directly focus on the development and implications of programs aimed to address PAC continuity issues found by the present research. Future research might also use findings from this qualitative exploration to develop a structured instrument to measure domains of care continuity. A survey instrument could produce quantitative data that may complement qualitative data such as these, and may facilitate mixed methods research and provide the methodology to assess facilities on their care continuity practices.

Although this research is not necessarily representative given the limits of our sample, our study included a substantial amount of data by the standards of qualitative research—interviews with 138 staff and 98 patients. However, our results are not intended to be generalizable and these hospitals, SNFs, and patients who agreed to participate may be different from others who did not participate.

This research is among the first to integrate the perspectives of both hospital and SNF staff with those of PAC patients on experiences during the hospital-SNF transition. It is of critical importance to consider the perspectives of patients, families, and members of both of the organizations involved in the hospital-SNF transfer when documenting problems and designing solutions. An understanding of problems encountered during the transition is the first step in attempting to ameliorate these concerns. We believe it is encouraging that there was considerable agreement among patients, family members, clinicians, and administrators as to what these problems are so that future efforts might more closely examine the issue of care coordination in a manner that includes patients and their families.

References

MedPAC. Report to the Congress. Medicare Payment Policy. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2018.

Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Association between skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1542–51.

Winblad U, Mor V, McHugh JP, Rahman M. ACO-affiliated hospitals reduced rehospitalizations from skilled nursing facilities faster than other hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):67–73.

Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):627–35.

Ackerly DC, Grabowski, DC. Post-acute care reform—beyond the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):689–91.

Mechanic R. Post-acute care—the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370(8):692–4.

Cross DA, Adler-Milstein J. Investing in post-acute care transitions: Electronic information exchange between hospitals and long-term care facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(1):30–4.

Jones C, Cumbler E, Honigman B, et al. Hospital to post-acute care facility transfers: Identifying targets for information exchange quality improvement. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(1):70–3.

Lage DE, Rusinak D, Carr D, Grabowski D, Ackerly DC. Creating a network of high-quality skilled nursing facilities: Preliminary data on the postacute care quality improvement experiences of an accountable care organization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:804–8.

McHugh JP, Foster A, Mor V, et al. Reducing hospital readmissions through preferred networks of skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1591–8.

Gardner R, Li Q, Baier R, Butterfield K, Coleman E, Gravenstein S. (2014). Is implementation of the Care Transitions Intervention associated with cost avoidance after hospital discharge? J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):878–84.

Kamermayer AK, Leasure AR, Anderson L. The effectiveness of transitions-of-care interventions in reducing hospital readmissions and mortality. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36(6):311–6.

Powers JS, Cox Z, Young J, Howell M, DiSalvo T. Critical pathways: Implementation of the Coleman Care Transitions Program in individuals hospitalized with congestive heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2442–4.

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, et al. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: The Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;42:1817–25.

Hirschman KB, Shaid E, McCauley K, Pauly MV, Naylor MD. Continuity of care: The Transitional Care Model. Online J Issues Nurs. 2015;20(3).

Jack BW, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SM, et al. An overview of the Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) Toolkit. (Prepared by Boston University under Contract No. HHSA290200600012i.) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2013. AHRQ Publication No. 12(13)-0084.

King BJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Roiland RA, Polnaszek BE, Bowers BJ, Kind AJ. The consequences of poor communication during transitions from hospital to skilled nursing facility: a qualitative study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1095–102.

Crabtree B, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research, 2nd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999.

Miles M, Huberman A, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014.

Padgett D. Qualitative and Mixed Methods in Public Health. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012.

Weston C, Gandell T, Beauchamp J, et al. Analyzing interview data: The development and evolution of a coding system. Qual Sociol. 2001;24(3):381–400.

Curry L, Nunez-Smith M. Mixed Methods in Health Sciences Research: A Practical Primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.

Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative Research for Nurses. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1996.

Lincoln Y, Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985.

Ritchie J, Lewis J, eds. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012.

Dizon ML, Zaltsmann R, Reinking C. Partnerships in transitions: Acute care to skilled nursing facility. Prof Case Manag. 2017;22(4):163–73.

Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on re-hospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 pt 1):1898–919.

Sinvani LD, Beizer J, Akerman M, et al. Medication reconciliation in continuum of care transitions: A moving target. J American Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:668–72.

Mukamel DB, Amin A, Weimer DL, Sharit J, Ladd H, Sorkin DH. When patients customize nursing home ratings, choices and rankings differ from the government’s version. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):714–9.

Funding

NIA P01 AG027296

Commonwealth Fund 20150004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Participants signed a consent form that was approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

John McHugh holds a consultancy with Navigant Consulting, Inc. Vincent Mor holds a consultancy with NaviHealth, Inc., holds equity with PointRight, Inc., and is the paid Chair of the Independent Quality Committee at HCR Manorcare. All the remaining authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 34.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gadbois, E.A., Tyler, D.A., Shield, R. et al. Lost in Transition: a Qualitative Study of Patients Discharged from Hospital to Skilled Nursing Facility. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 102–109 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4695-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4695-0