Abstract

Background

Prior cross-sectional research has found that generalists have lower rates of academic advancement than specialists and basic science faculty.

Objective

Our objective was to examine generalists relative to other medical faculty in advancement and academic productivity.

Design

In 2012, we conducted a follow-up survey (n = 607) of 1214 participants in the 1995 National Faculty Survey cohort and supplemented survey responses with publicly available data.

Participants

Participants were randomly selected faculty from 24 US medical schools, oversampling for generalists, underrepresented minorities, and senior women.

Main Measures

The primary outcomes were (1) promotion to full professor and (2) productivity, as indicated by mean number of peer-reviewed publications, and federal grant support in the prior 2 years. When comparing generalists with medical specialists, surgical specialists, and basic scientists on these outcomes, we adjusted for gender, race/ethnicity, effort distribution, parental and marital status, retention in academic career, and years in academia. When modeling promotion to full professor, we also adjusted for publications.

Key Results

In the intervening 17 years, generalists were least likely to have become full professors (53%) compared with medical specialists (67%), surgeons (66%), and basic scientists (78%, p < 0.0001). Generalists had a lower number of publications (mean = 44) than other faculty [medical specialists (56), surgeons (57), and basic scientists (83), p < 0.0001]. In the prior 2 years, generalists were as likely to receive federal grant funding (26%) as medical (21%) and surgical specialists (21%), but less likely than basic scientists (51%, p < 0.0001). In multivariable analyses, generalists were less likely to be promoted to full professor; however, there were no differences in promotion between groups when including publications as a covariate.

Conclusions

Between 1995 and 2012, generalists were less likely to be promoted than other academic faculty; this difference in advancement appears to be related to their lower rate of publication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the last several decades, the US has seen declining numbers of physicians recruited and retained in primary care.1 – 5 As a result, the primary care workforce is facing severe shortages compared to their subspecialty counterparts.6 Reasons cited for this trend include lower reimbursement rates despite equal or more work hours,7 , 8 a greater burden of administrative responsibilities and paperwork,9 , 10 and higher rates of dissatisfaction11 compared with physicians in specialty care.

In addition to these pressures, academic generalists face additional career challenges. Generalists have lower rates of faculty promotion and advancement compared to their counterparts in medical and surgical specialties and basic sciences, possibly due to differing expectations.12 One key measure of academic productivity is in the number of publications produced. Several studies have found that generalists have fewer peer-reviewed publications compared to their subspecialty colleagues.12 , 13 However, prior work on this topic has not been nationally based or studied from a longitudinal perspective.

We therefore conducted this study of academic medical faculty to understand whether productivity and advancement differs for generalists relative to other types of medical facultyand had changed since prior studies on this topic.

Methods

Our study is a 17-year follow-up to the 1995 National Faculty Survey (NFS). In 1995, the NFS was conducted to examine the status of female, minority and academic generalists in US medical schools. All medical schools in the continental US with at least 200 faculty, 50 women, and 10 minority faculty were identified, and from these 106 schools, a cohort of 24 schools was randomly selected. These schools were balanced for AAMC geographic region and private/public status. Six full-time faculty members were randomly selected within each of 24 cells: 4 areas of medical specialization (generalist, medical specialties, surgical specialties, and basic sciences) stratified by three graduation cohorts (before 1970, 1970–1980, after 1980) and by gender. Because the initial survey was designed to look at under-represented faculty, senior women, and generalists in academic medicine, all underrepresented minorities, women who graduated before 1970, and generalists were over-sampled. In 1995, 60% of the Faculty Roster Sample completed the survey for a total of 1790 full-time faculty responding. A subset of 1335 faculty indicated that they were willing to participate in future studies; this created the sample for our follow-up study.

Our follow-up study was initiated with a web-based search for current location and contact information of the 1995 faculty cohort using name, academic specialty, and 1995 institutional affiliation. Where valid email addresses were identified, we invited them to participate in a follow-up survey online or by mailing in a printed version. Non-responders were sent up to four follow-up reminder emails; those without email addresses were contacted by telephone or mailing address. The follow-up survey used gender, year of birth, and race/ethnicity to ensure correct linkage of the data to the original survey data. Subjects who completed the survey were provided a modest remuneration.

For those who did not respond to the follow-up survey, we developed a methodology to access publicly available databases in order to assess our metrics of productivity. Using name, departmental affiliation, year of birth, and academic institution in 1995 as personal identifiers, we searched for the subject’s current academic affiliation or professional activities outside of academic medicine and included data where a match occurred. We searched the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT) website14 for federal funding in the prior 2 years and the bibliographic database Scopus15 for total number of peer-reviewed publications through 2012. We chose to use only the past 2 years of federal funding in order to include all participants in our analysis, including those who did not complete the survey. We conducted a validity assessment of this methodology by reviewing the Scopus publication number for all participants who returned the online survey and determined consistency between self-reported outcomes and data available from these databases.

The follow-up 113-item survey (available on request) was conducted during the 2012–13 academic year. We asked respondents their current academic rank and dichotomized rank as professor versus all others. Departmental affiliation was grouped into four categories: generalist specialties, medical specialties, surgical specialties, and basic sciences. Generalists included self-identified pediatricians, geriatricians, family practitioners, and general internists. Covariates included race/ethnicity, dichotomized as white versus minority (African American, Hispanic, Asian, and multiracial or other). Percent effort distribution was calculated for administrative, research, clinical, and teaching activities. Marital status was dichotomized as married/partnered versus all others in 1995. Parental status was dichotomized as any versus no children in 1995. Current professional setting was dichotomized as academia versus other. We calculated number of years since first academic appointment based upon data from the 1995 survey.

Outcome measures of productivity included total number of peer-reviewed articles published as of 2012 and H-index, a measure of publication impact.16 The H-index was assessed to determine whether, regardless of the number of publications, the impact of papers by generalists might differ from those of their specialty colleagues. H-index results were similar with and without self-citation; therefore, we included self-citation in the measure. We also examined presence of any federal grant funding as Primary Investigator over the past 2 years prior to our follow-up survey as a measure of productivity. The H-index was then compared across specialties using a multivariate analysis.

Institutional review board approval for the study was received from Boston University, Tufts Medical Center, and for Massachusetts General Hospital through the Master Reliance Agreement with Tufts Medical Center.

Analysis Plan

Descriptive statistics were calculated for subject characteristics and were compared across specialties. We conducted bivariate comparisons of each outcome by specialty type. Adjusted negative binomial regression models were developed to assess associations between specialty and number of peer-reviewed articles and H-index. Adjusted logistic regression analyses were used to assess the associations between specialty and current grant funding and rank. Backward selection was used to select a final set of variables for each adjusted model, with gender and race/ethnicity forced into all models. Variables significant at p < 0.10 in bivariate analyses were candidate variables in the multivariable models; these included marital status, parental status, professional setting, and years since first academic appointment. Rank was also modeled with and without adjustment for number of publications. Covariates were retained if the association reached the p < 0.05 level in the multivariable model. We tested for gender interaction with specialty in the publication and rank models. All data analyses were performed using SAS v9.4.

Results

Of the 1335 participants who agreed to be followed for future studies, 60 died prior to follow-up, leaving a potential sample of 1275 participants, of whom 52 were excluded because of lack of data on specialty and 9 with no available outcome data. This left a total of 1214 subjects, of whom 607 (50%) participated in the follow-up survey and 607 (50%) for whom data on rank, total refereed articles, and federal grants were acquired from publicly available sources.

Table 1 provides demographic information for the sample, stratified by professional specialty. The majority of faculty in all specialties was white (80% generalists, 77% medicine specialists, 80% surgical specialists, and 86% of basic scientists). By study design, women were nearly evenly represented in each specialty (generalists 53%, medical specialists 52%, surgical specialist 44%, basic scientists 48%; p = 0.15). The mean time since first academic appointment differed by department (p < 0.0001) with generalists and surgical specialists at 27 years, while medical specialists and basic scientists were slightly more senior with 30 and 31 years, respectively. Marital and parental status in 1995 did not differ across the specialties. Effort distribution differed across specialties with generalists and medical subspecialists having more administrative responsibilities than surgical specialists and basic scientists (20% of time for each, compared with 15% and 18%, respectively; p = 0.002); research responsibilities were a greater percent effort for basic scientists relative to clinicians (58% compared with 18–24%, p < 0.0001), and clinical load was a greater percent effort for clinicians relative to basic scientists (range 38–46% compared with 9%, p < 0.0001), the majority of whom are not clinically trained. Retention in academic medicine after 17 years varied across specialties, with 78% of basic scientists retained in academic medicine compared with 72% of generalists, 67% of medical specialists, and 68% of surgical specialists (p = 0.01).

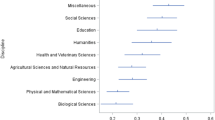

Our unadjusted analysis showed significant differences across specialties in measures of productivity (Table 2). Basic scientists were more likely to be the PI or Co-PI on federal grants within the previous 2 years at 51% compared to 26% of generalists and 21% of medical and surgical specialists, respectively (p < 0.0001). Mean number of peer-reviewed publications across the career also differed across specialties with 83 for basic scientists, followed by 57 for medical specialists, 57 for surgical specialists, and 44 for generalists (p < 0.0001). The mean H-index citation measure for generalists was 14.2, compared with 17.3 and 17.4 for surgical and medical specialists, respectively, and 25.0 for basic scientists (p < 0.0001). Promotion to rank of full professor differed across the specialties with 78% of basic scientists promoted to professor, 67% of medical specialists, 66% of surgical specialists, and only 53% of generalists (p < 0.0001).

Table 3 shows the adjusted differences between generalists and the other specialties comparing measures of productivity, including acquisition of federal grants, publications and citation impact in refereed journals, and promotion to rank of full professor over the period from the initial study in 1995 to follow-up study in 2012–13. The odds that generalists received a federal grant as PI or Co-PI in the prior 2 years were not statistically different when compared to medical and surgical specialists (OR 0.84, 95% CI = 0.58–1.2 and OR 0.82, 95% CI = 0.53–1.3, respectively). Basic scientists, however, were 3.1 times more likely to receive a federal grant than generalists (95% CI = 2.1–4.4) during that time period.

When comparing publications, generalists published significantly fewer peer-reviewed papers than their colleagues in all the other specialties. Medical and surgical specialists authored 1.3 times as many papers as generalists (95% CI = 1.1–1.5 and 1.1–1.6, respectively) and basic scientists produced 1.8 times as many papers (95% CI = 1.6–2.2). The negative binomial analysis provides estimates of the relative number of publications in the different groups. After controlling for gender, race, and years since first appointment, surgical specialists had higher mean H-index values compared with generalists (relative number 1.2, 95% CI 1.05–1.4). Medical specialists (1.2, 95% CI 1.08–1.4) and basic scientists (1.7, 95% CI 1.5–2.0) also had higher H-index values compared with generalists. Of note, when comparing publication rates across specialties, we also modeled for interaction with gender, and no significant interaction was identified between gender and department.

In the model that adjusted for number of peer-reviewed publications, the odds of promotion to the rank of full professor by 2012–13 did not differ for generalists in comparison to any of the specialties, with an OR of 0.92 compared to basic scientists (95% CI = 0.56–1.5), 0.90 compared with medical specialists (95% CI = 0.59–1.4), and 1.2 compared with surgical specialists (95% CI = 0.73–2.0). Given that publications are strongly considered in decisions regarding promotion, we repeated the analysis for rank with publications removed and found that the odds of promotion were lower for generalists than for all other specialties. Basic scientists had 2.3 times the odds of being promoted to professor compared to generalists (95% CI = 1.5–3.5), medical specialists 1.5 times (95% CI = 1.0–2.2) and surgical specialists 2.1 times (95% CI = 1.3–3.2). In addition, when we modeled our multivariate analysis for rank, we found no interaction between publications and gender.

Discussion

In this follow-up to the National Faculty Survey, we found that generalists are less likely to be promoted to full professor over the course of their career relative to their basic science, medical, and surgical subspecialty colleagues. Our article focused on two traditional measures of academic promotion: publication and research grant attainment. While other factors are often considered, in US medical schools these two factors are typically most heavily weighted by faculty promotions committees. Generalists had the same likelihood of recently obtaining federal grants, but had a lower rate of publication and a lower H-index. When adjusted for other factors including, gender, race, academic setting, parental and partner status, and publication rate, we found that generalists were promoted at the same rate as their colleagues in other specialties. However, as publication rate is a major criterion for academic promotion, when publications were not adjusted for, we found generalists less likely to be promoted than their colleagues, suggesting that the lower promotion of generalists compared to their colleagues is closely tied to their lower rates of publication.

Our findings are consistent with prior cross-sectional research showing that generalists have fewer peer-reviewed publications compared to their counterparts in the subspecialties.12 , 13 Research productivity has long been a source of discussion in academic general medicine. One study on the attitudes of deans from 83 medical schools toward their primary care faculty found that while deans considered research to be important, they rated their primary care faculty’s research skills and productivity low in comparison to non-primary care faculty.17 Another study found that generalist faculty spent only half a day or less on research activities, yielding low rates of scholarly products.18 After controlling for number of publications, we found that generalists were promoted at the same rate as specialists and basic scientists. These findings suggest that producing peer-reviewed publications during one’s career trajectory is tightly associated with the promotions process and that generalists fall short on this critical measure of productivity.

In the setting of similar federal grant attainment between generalists and specialists, we theorized that generalists’ publications, while fewer in number, could have a greater impact than those of their specialty and basic science colleagues. However, we found that generalist publications had a lower H-index indicating both a lower citation rate and lower total number of publications for a given author. Both impact and quantity of publications are typically considered in the academic promotions process, and generalists in our study were lower in both areas. This does not indicate that generalists’ publications are unimportant, but may reflect lower impact MedEd journals or that their impact is clinical or curricular and not included in the H-index.

We also considered that women are overrepresented among generalists and that women have been shown to have lower rates of both academic promotion and publication in prior studies.19 This raised the possibility of an interaction between generalist specialty and gender; however, in our multivariable analysis, no such interaction was found.

Other possible explanations for the decreased publication rate of generalists compared to their specialist and basic science peers may be related to the structure of the job itself. Clinical expectation for a full-time academic generalist is typically 32 or 36 hours per week of patient care; there is rarely protected time for research or other academic pursuits especially early in the career. Prior studies have shown that for every hour a generalists spends seeing patients, another hour is spent in non-face-to-face patient care responsibilities; this likely holds true regardless of academic or community setting. In addition to the likelihood that a clinical “full-time equivalent” varies between academic specialties, there is also a difference in the amount of additional non-visit-related paperwork required of a primary care doctor as compared with a specialist.10 , 20 These differences may give specialists more flexible time in which to conduct their academic pursuits. In addition, academic generalists tend to be heavily involved in medical education, at both the student and resident levels. Unfunded responsibilities for teaching and mentoring contribute to the competing demands on generalist faculty time.21 These pursuits, while important to medical schools, are not considered “scholarly” if they do not involve publications.

Studies of academic family practitioners have shown that a culture of publication, or lack thereof, is associated with level of research productivity. A national study found that 80% of academic family practitioners had 1 half day per week or less without other clinical obligations,18 and experienced mixed messages regarding institutional priorities around clinical versus research time for generalists. The conclusions reached in that study were that time spent on research, availability of research networks, mentoring, and a structure supportive of research were more important than any demographic variable in predicting publication productivity.

One limitation of our study was the response rate of 50%; however, we were able to acquire current academic rank, publications, and acquisition of federal grants in the last 2 years using publicly available data sets, allowing us to examine our outcomes for most subjects. In our multivariate analysis, we used information from the 1995 survey for marital and parental status, and while these may not always remain constant across a career, the 1995 data reflect the status of the faculty participants during the time in their careers that they need to be most productive in order to be promoted. The sample included only full-time faculty in 1995, thus preventing generalization of findings to part-time faculty. In addition, while minorities were oversampled in the 1995 study, the total number in this study is still small, which may limit generalizability to non-white faculty. Our study was robust in that it was a multicenter longitudinal follow-up covering sufficient years for potential promotion of all subjects to full professor.

While it is discouraging to find that generalists are promoted at a lower rate than other faculty colleagues, identifying a lower publication rate as the main underlying factor allows us to focus on identifying the reasons generalists publish fewer articles in refereed journals than their subspecialty and basic science peers. Clinical burden, time spent teaching, administrative and other less publication-driven responsibilities, as well as attitudes among leadership may impact resources and the support generalist faculty receive for scholarly work. The current climate in academic medicine over-weights research and undervalues the work of generalists, who maintain greater responsibilities for teaching and providing clinical care coordination to achieve excellent patient outcomes. The criteria for promotion of generalists must appropriately quantify and value contributions to teaching and clinical care, while ensuring that adequate time is protected for scholarly work.

References

Schwartz MD, Linzer M, Babbott D, Divine GW, Broadhead E. Medical student interest in internal medicine. Initial report of the society of general internal medicine interest group survey on factors influencing career choice in internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(1):6–15.

Schwartz MD, Basco WT Jr, Grey MR, Elmore JG, Rubenstein A. Rekindling student interest in generalist careers. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(8):715–724.

Schwartz MD, Durning S, Linzer M, Hauer KE. Changes in medical students’ views of internal medicine careers from 1990 to 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(8):744–749.

Lewis CE, Prout DM, Chalmers EP, Leake B. How satisfying is the practice of internal medicine? A national survey. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(1):1–5.

Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1154–1164.

Bodenheimer T (2006) Primary care—will it survive?. N Engl J Med 355(9):861- 86444–749

Leigh JP, Tancredi D, Jerant A, Kravitz RL. Annual work hours across physician specialties. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1211–1213.

Steinbrook R. Easing the shortage in adult primary care—is it all about money? N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2696–2699.

Casalino LP, Nicholson S, Gans DN, et al. What does it cost physician practices to interact with health insurance plans? Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(4):w533–w543.

Baron RJ. What’s keeping us so busy in primary care? A snapshot from one practice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1632–1636.

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385.

Kempainen RR, McKone EF, Rubenfeld GD, Scott CS, Tonelli MR. Publications and extramural activities of general internal medicine and medicine subspecialty clinician-educators: a multicenter study. Acad Med. 2005;80(3):238–243.

Kempainen RR, McKone EF, Rubenfeld GD, Scott CS, Tonelli MR. Comparison of scholarly productivity of general and subspecialty clinician-educators in internal medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(4):323–328.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT) http://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm. Accessed on December 1, 2016.

Scopus. http://www.scopus.com/. Accessed on December 1, 2016.

Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(46):16569–16572.

Friedman RH, Wahi-Gururaj S, Alpert J, et al. The views of US medical school deans toward academic primary care. Acad Med. 2004;79(11):1095–1102.

Brocato JJ, Mavis B. The research productivity of faculty in family medicine departments at US medical schools: a national study. Acad Med. 2005;80(3):244–252.

Reed DA, Enders F, Lindor R, McClees M, Lindor KD. Gender differences in academic productivity and leadership appointments of physicians throughout academic careers. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):43–47.

Gottschalk A, Flocke SA. Time spent in face-to-face patient care and work outside the examination room. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):488–493.

Luckhaupt SE, Chin MH, Mangione CM, et al. Mentorship in academic general internal medicine. Results of a survey of mentors. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1014–1018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funders

The project described was supported by award no. R01 GM088470 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and Office of Research in Women’s Health, National Institutes of Health.

Prior Presentations

Oral presentations at the Society for General Internal Medicine (SGIM) New England Regional Meeting in Boston, MA, on March 27, 2015, and the 38th SGIM Annual Meeting in Toronto, Canada, on April 24, 2015.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blazey-Martin, D., Carr, P.L., Terrin, N. et al. Lower Rates of Promotion of Generalists in Academic Medicine: A Follow-up to the National Faculty Survey. J GEN INTERN MED 32, 747–752 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3961-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3961-2