ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Despite improvements in the diagnosis and treatment of depression, primary care provider (PCP) discussion regarding suicidal thoughts among patients with depressive symptoms remains low.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether a targeted depression public service announcement (PSA) video or an individually tailored interactive multimedia computer program (IMCP) leads to increased primary care provider (PCP) discussion of suicidal thoughts in patients with elevated risk for clinical depression when compared to an attention control.

DESIGN

Randomized control trial at five different healthcare systems in Northern California; two academic, two Veterans Affairs (VA), and one group-model health maintenance organization (HMO).

PARTICIPANTS

Eight-hundred sixty-seven participants, with mean age 51.7; 43.9 % women, 43.4 % from a racial/ethnic minority group.

INTERVENTION

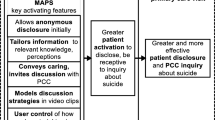

The PSA was targeted to gender and socio-economic status, and designed to encourage patients to seek depression care or request information regarding depression. The IMCP was an individually tailored interactive health message designed to activate patients to discuss possible depressive symptoms. The attention control was a sleep hygiene video.

MAIN MEASURES

Clinician reported discussion of suicidal thoughts. Analyses were stratified by depressive symptom level (Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] score < 9 [mild or lower] versus ≥ 10 [at least moderate]).

KEY RESULTS

Among patients with a PHQ-9 score ≥ 10, PCP discussion of suicidal thoughts was significantly higher in the IMCP group than in the control group (adjusted odds ratio = 2.33, 95 % confidence interval = 1.5, 5.10, p = 0.03). There were no significant effects of either intervention on PCP discussion of suicidal thoughts among patients with a PHQ-9 score < 9.

CONCLUSIONS

Exposure of patients with at least moderate depressive symptoms to an individually tailored intervention designed to increase patient engagement in depression care led to increased PCP discussion of suicidal thoughts.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

CDC. Injury Center: violence prevention. 2009; http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/statistics/index.html. Accessed March 6, 2014.

WHO. WHO gobal health observatory—suicide deaths. 2013; http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/. Accessed March 6,2014.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289(23):3095–3105.

Cooper J, Kapur N, Webb R, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):297–303.

Milner A, Sveticic J, De Leo D. Suicide in the absence of mental disorder? A review of psychological autopsy studies across countries. Int J Soc Psychiatry. May 11 2012.

Yoshimasu K, Kiyohara C, Miyashita K. Suicidal risk factors and completed suicide: meta-analyses based on psychological autopsy studies. Environ Health Prev Med. 2008;13(5):243–256.

Cavanagh JT, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33(3):395–405.

Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):909–916.

Vassilas CA, Morgan HG. General practitioners’ contact with victims of suicide. BMJ. 1993;307(6899):300–301.

Bostwick JM, Rackley S. Addressing suicidality in primary care settings. Curr Psychiatr Rep. 2012;14(4):353–359.

Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;294(16):2064–2074.

DHHS S-. National strategy for suicide prevention: goals and objectives. 2001; www.sprc.org/library/nssp.pdf. Accessed March 6,2014.

Gunnell D, Metcalfe C, While D, et al. Impact of national policy initiatives on fatal and non-fatal self-harm after psychiatric hospital discharge: time series analysis. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2012;201(3):233–238.

Uncapher H, Arean PA. Physicians are less willing to treat suicidal ideation in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(2):188–192.

Kaplan MS, Adamek ME, Calderon A. Managing depressed and suicidal geriatric patients: differences among primary care physicians. Gerontologist. 1999;39(4):417–425.

Frankenfield DL, Keyl PM, Gielen A, Wissow LS, Werthamer L, Baker SP. Adolescent patients–healthy or hurting? Missed opportunities to screen for suicide risk in the primary care setting. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(2):162–168.

Milton J, Ferguson B, Mills T. Risk assessment and suicide prevention in primary care. Crisis. 1999;20(4):171–177.

Nutting PA, Dickinson LM, Rubenstein LV, Keeley RD, Smith JL, Elliott CE. Improving detection of suicidal ideation among depressed patients in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):529–536.

Zisook S, Anzia J, Atri A, et al. Teaching evidence-based approaches to suicide risk assessment and prevention that enhance psychiatric training. Compr Psychiatry. Sep 17 2012.

Feldman MD, Franks P, Duberstein PR, Vannoy S, Epstein R, Kravitz RL. Let’s not talk about it: suicide inquiry in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(5):412–418.

Vannoy SD, Fancher T, Meltvedt C, Unutzer J, Duberstein P, Kravitz RL. Suicide inquiry in primary care: creating context, inquiring, and following up. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(1):33–39.

Bell RA, Franks P, Duberstein PR, et al. Suffering in silence: reasons for not disclosing depression in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(5):439–446.

Inskip HM, Harris EC, Barraclough B. Lifetime risk of suicide for affective disorder, alcoholism and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 1998;172:35–37.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

Blair-West GW, Cantor CH, Mellsop GW, Eyeson-Annan ML. Lifetime suicide risk in major depression: sex and age determinants. J Affect Disord. 1999;55(2–3):171–178.

Blair-West GW, Mellsop GW, Eyeson-Annan ML. Down-rating lifetime suicide risk in major depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95(3):259–263.

O’Connor E, Gaynes BN, Burda BU, Soh C, Whitlock EP. Screening for and treatment of suicide risk relevant to primary care: a systematic review for the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. Apr 23 2013.

Tancredi DJ, Slee CK, Jerant A, et al. Targeted versus tailored multimedia patient engagement to enhance depression recognition and treatment in primary care: randomized controlled trial protocol for the AMEP2 study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):141.

Kravitz RL, Franks P, Feldman MD, et al. Patient engagement programs for recognition and initial treatment of depression in primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310(17):1818–1828.

Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Bell RA, et al. An academic-marketing collaborative to promote depression care: a tale of two cultures. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(3):411–419.

Jerant A, Sohler N, Fiscella K, Franks B, Franks P. Tailored interactive multimedia computer programs to reduce health disparities: opportunities and challenges. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):323–330.

Kreuter MW, Skinner CS. Tailoring: what’s in a name? Health Educ Res. 2000;15(1):1–4.

Ryan GL, Skinner CS, Farrell D, Champion VL. Examining the boundaries of tailoring: the utility of tailoring versus targeting mammography interventions for two distinct populations. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(5):555–566.

Epstein A. Common sleeping problems. HealthiNation. 2011.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233.

Vannoy SD, Robins LS. Suicide-related discussions with depressed primary care patients in the USA: gender and quality gaps. A mixed methods analysis. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2), e000198.

Funding

The work was supported by grant 1R01MH079387 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Role of the Funding Source

The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01144104

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, R., Franks, P., Jerant, A. et al. The Effect of Targeted and Tailored Patient Depression Engagement Interventions on Patient–Physician Discussion of Suicidal Thoughts: A Randomized Control Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 29, 1148–1154 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2843-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2843-8