Abstract

In its recently published Green Paper, the European Commission (Audit policy: lessons from the crisis. Brussels, 2010) discusses various methods to enhance the reliability of audits and to re-establish trust in the financial market. The Commission primarily focuses on increasing auditor independence and on reducing the high level of audit market concentration. Based on a model in the tradition of the circular market matching models introduced by Salop (Bell J Econ 10(1):141–156, 1979), we show that prohibiting non-audit services as a measure intended to improve auditor independence can have counter-productive secondary effects on audit market concentration. In fact, our model demonstrates that incentives for independence and the structure of the audit market are simultaneously determined. Because market shares are endogenous in our model, it is not even clear that prohibiting non-audit services indeed increases an auditor’s incentive to remain independent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We derive the conditions that must be fulfilled for the assumptionm > n to emerge endogenously below.

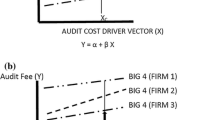

Our results from analyzing fee data from Switzerland and the USA show that clients of the (three and four) respective market leaders indeed demanded considerably more non-audit services than clients of the small audit firms. For the years 2002–2009, we observed an average ratio between non-audit fees and audit fees in Switzerland and in the USA of 30.57 and 21.67 % for clients of non-Big X audit firms, whereas this ratio was 67.84 and 35.55 % for clients of Big X auditors.

The question of whether competition in the consulting market affects competition in the market for audit services is not the focus of this paper (for a formal analysis of this argument, see Wu2006).

The large audit firms’ higher number of partners and assistants also contributes to the increased costs associated with acquiring and retaining audit staff and the higher expenses incurred for professional training. Chang et al. (2008) found empirical evidence that the number of training hours of partners and assistants is higher in big firms compared to middle-sized and small audit firms.

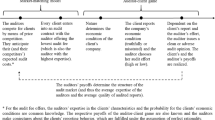

Based on data for US audits performed by an international public accounting firm, O’Keefe et al. (1994) found that client characteristics explain more than 80 % of the cross-sectional variation in the quantity of professional labor input. Measures for the client characteristics used in this study (client size, complexity, and risk) were similar to those used in prior audit pricing studies. Fee studies also indicate that the characteristics of the client and the auditor-client relationship account for a large degree of the variance in audit fees (for a meta-analysis of the audit fee studies, see Hay et al.2006).

The results we obtain would be qualitatively similar if we assumed a concave or a convex cost function.

Not only do small accounting firms face severe challenges in obtaining audit contracts from large clients, but it also seems that they are not very interested in serving this market segment (see GAO2008). In addition, there is empirical evidence that the choice of the auditor depends on client characteristics (see Knechel et al.2008).

See Simunic (1984), Simon (1985), DeBerg et al. (1991), and Bell et al. (2001) (US); Butterworth and Houghton (1995) and Craswell and Francis (1999) (Australia); and Ezzamel et al. (1996) (UK). Palmrose (1986), however, documented a positive relationship between audit fees charged by one supplier and non-audit fees paid to a different supplier that did not perform the audit, which contradicts the argument for knowledge spillovers.

Using data on audit staff hours, O’Keefe et al. (1994) did not find evidence of knowledge spillovers from management consulting and/or tax consulting to audit services. Davis et al. (1993) found a weakly significantpositive relationship between tax services and different audit effort measures and between accounting-related consulting services and audit hours weighted by billing-rate ratios. If additional effort is required for audits of clients who also purchase non-audit services and the demand for auditing is inelastic (see Beck et al.1988, pp. 52–54), these results do not support the existence of audit production efficiencies arising from knowledge spillovers.

Antle et al. (2006) also have used a simultaneous-equations specification to estimate audit and non-audit fee models, finding evidence consistent with the existence of knowledge spillovers. Their result thus stands in opposition to the findings of Whisenant et al. (2003). Their fee models, however, might be mis-specified, since important variables measuring audit effort are not included.

In fact, numbers of audit firms betweenm*/2 andm* would also be possible equilibria if we considered a sequential market entry decision. Since we do not focus on the auditors’ specialization decision, in the following sections we only consider the number of audit firms for which the zero-profit contribution is fulfilled.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the profession is seriously affected by decreasing hourly rates for auditing, which is seen as a springboard for attracting clients to buy higher-margin non-audit services (see, for example, Göggelmann2010). The reasoning for “dumping pricing” is related to the overcapacities of audit firms (see o.V.2009). There is, however, also evidence indicating that the decrease in revenues from non-audit services caused by the implementation of regulatory restrictions is being offset by a substantialincrease in audit fees and in higher profit margins for audit services (see Weil2004,2005; Gullapalli2005).

Based on an empirical study, Quick and Sattler (2011b) make a similar argument regarding the interrelation between restricting the fee an audit firm is allowed to earn from a single audit client to a certain percentage (also viewed as a possible means to increase auditor independence) and the level of audit market concentration.

Khurana and Raman (2006) and Quick and Warming-Rasmussen (2009), for example, document the fact that addressees of financial reports perceive auditor independence to be impaired if auditing and consulting services are acquired from the same supplier, and Frankel et al. (2002) report a positive relationship between non-audit fees and the magnitude of discretionary accruals. Larcker and Richardson (2004) and Lim and Tan (2008), in contrast, observe that audit quality increases with the level of non-audit services, and Jenkins and Krawczyk (2001) find a favorable effect on perceived auditor independence in appearance (or no effect). Quick and Sattler (2011a) demonstrate that attestation services and tax consulting services do not significantly affect earnings management, whereas consulting services from the category “miscellaneous” impair the quality of financial statements.

The qualitative results of our analysis do not change if audit firmi audits clients it is specialized in and provides consulting services to clients outside this region: The profit contribution from consulting would not change, but the average consulting fees would increase byc C /2n. Which of these cases is more costly for the clients depends on the relation between\( \alpha \cdot {{c}_{A}}^{l} \) andc C .

From fiscal years 2002–2009, the three largest audit firms (KPMG, PricewaterhouseCoopers, and Ernst & Young) audited on average 86 % of listed corporations headquartered in Switzerland (not including financial institutions and real estate or insurance companies; data fromThomson One,Audit Analytics, and from annual reports). Thus, the Swiss audit market can serve as an example of a separated audit market.

Between 2002 and 2009, the largest four audit firms in the USA (KPMG, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Ernst & Young, and Deloitte) provided audit services to only 56 % of the listed companies headquartered in the USA, on average (data fromThomson One,Audit Analytics, and from annual reports). Thus, small audit firms had a non-negligible market share even in the market for listed companies, at least if the number of clients is used as a measure of calculating the concentration ratio.

This result, however, is straightforward, since we did not assume that audit firms incur additional fixed costs for providing consulting services to their clients.

For the case in which consulting also affects the costs for auditing small clients that are similar to the large clients consuming consulting services, our results are unaffected if the more restrictive restriction\( \gamma \cdot {{c}_{0}}^{l}>\sqrt{2\cdot {{c}_{A}}^{s}\cdot {{c}_{F}}^{s}} \) is fulfilled.

If the assumption does not hold because the number of large audit firmsn is sufficiently high and\( {{c}_{0}}^{l} \) is sufficiently low, the large audit firmi effectively competes with the nearest other large audit firmi − 1 and could charge a fee of\( {{\textit{fee}}^{i}}(0)={{c}_{0}}^{l}+{{{c}_{A}}^{l}}/{n}\;. \)

A similar result holds for the case in which not all small audit firms in between two large audit firms effectively compete with the large audit firms. If small audit firms in a relatively large distance to the nearest large audit firm compete with each other, these small audit firms can be investigated as in reference situation I. The analysis of the audit firms relatively near to the large audit firms’ positions is the same as described in this section.

Literature

Antle R, Gordon E, Narayanamoorthy G, Zhou L (2006) The joint determination of audit fees, non-audit fees, and abnormal accruals. Rev Quant Financ Account 27(3):235–266

Barkess L, Simnett R (1994) The provision of other services by auditors: independence and pricing issues. Account Bus Res 24(94):99–108

Beck PJ, Wu MGH (2006) Learning by doing and audit quality. Contemp Account Res 23(1):1–30

Beck PJ, Frecka TJ, Solomon I (1988) A model of the market for MAS and audit services: knowledge spillovers and auditor-auditee bonding. J Account Lit 7:50–64

Bell TB, Landsman WR, Shackelford DA (2001) Auditors’ perceived business risk and audit fees: analysis and evidence. J Account Res 39(1):35–43

Bigus J, Zimmermann R-C (2008) Non-audit fees, market leaders and concentration in the German audit market: a descriptive analysis. Int J Audit 12(3):159–179

Butterworth S, Houghton KA (1995) Auditor switching: the pricing of audit services. J Bus Financ Account 22(3):323–344

Cairney TD, Young GR (2006) Homogenous industries and auditor specialization: an indication of production economies. Audit J Pract Theory 25(1):49–67

Chan DK (1999) “Low balling” and efficiency in a two-period specialization model of auditing competition. Contemp Account Res 16(4):609–642

Chang B-G, Chen Y-S, Lee C-C (2008) The association between continuing professional education and financial performance of public accounting firms. Int J Hum Resour Manag 19(9):1720–1737

Craswell AT (1999) Does the provision of non-audit services impair independence? Int J Audit 3(1):29–40

Craswell AT, Francis JR (1999) Pricing initial audit engagements: a test of competing theories. Account Rev 74(2):201–216

Davis LR, Ricchiute DN, Trompeter G (1993) Audit effort, audit fees, and the provision of nonaudit services to audit clients. Account Rev 68(1):135–150

DeAngelo LE (1981) Auditor independence, “low balling”, and disclosure regulation. J Account Econ 3(2):113–127

DeBerg CL, Kaplan SE, Pany K (1991) An examination of some relationships between non-audit services and auditor change. Account Horiz 5(1):17–28

Dopuch N (1988) Discussion comments of “An empirical analysis of the relationship between MAS involvement and auditor tenure: implications for auditor independence”. J Account Lit 7:85–91

European Commission (2010) Audit policy: lessons from the crisis. Green Paper. Brussels

Ewert R (1990) Wirtschaftsprüfung und asymmetrische Information. Springer, Berlin

Ewert R, London Economics (2006) Study on the economic impact of auditors’ liability regimes (MARKT/2005/24/F). Final report to EC-DG Internal Market and Services

Ezzamel M, Gwilliam DR, Holland KM (1996) Some empirical evidence from publicly quoted UK companies on the relationship between the pricing of audit and non-audit services. Account Bus Res 27(1):3–16

Frankel R, Johnson M, Nelson K (2002) The relation between auditors’ fees for nonaudit services and earnings management. Account Rev 77(Suppl):71–105

United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) (2008) Report to congressional addressees (GAO-08-163 Public Companies, Jan 9, 2008): audits of public companies – continued concentration in audit market for large public companies does not call for immediate action. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08163.pdfhttp://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08163.pdf

Göggelmann U (2010) Kampf um den Kuchen. Financial Times Deutschland (13.10.2010):23 f.

Graham LE (1988) Discussion comments of “An empirical analysis of the relationship between MAS involvement and auditor tenure: implications for auditor independence”. J Account Lit 7:92–94

Gullapalli D (2005) Audit fees are on rise as companies pony up: payments for consulting and other services shrink, in big change from 2000. Wall Street Journal (25.03.2005):C3

Hay D, Knechel RW, Wong N (2006) Audit fees: a meta-analysis of the effect of supply and demand attributes. Contemp Account Res 23(1):141–191

Hogan CE, Jeter DC (1999) Industry specialization by auditors. Audit J Pract Theory 18(1):1–17

Hotelling H (1929) Stability in competition. Econ J 39(153):41–57

Jenkins JG, Krawczyk K (2001) The influence of nonaudit services on perceptions of auditor independence. J Appl Bus Res 17(3):73–78

Khurana IK, Raman KK (2006) Do investors care about the auditor’s economic dependence on the client? Contemp Account Res 23(4):977–1016

Knechel RW, Niemi L, Sundgren S (2008) Determinants of auditor choice: evidence from a small client market. Int J Audit 12(1):65–88

Köhler AG, Marten K-U, Ratzinger NVS, Wagner M (2010) Prüfungshonorare in Deutschland—Determinanten und Implikationen. Z Betriebswirtsch 80(1):5–29

Larcker D, Richardson S (2004) Fees paid to audit firms, accrual choices, and corporate governance. J Account Res 42(3):625–658

Lim CY, Tan HT (2008) Non-audit service fees and audit quality: the impact of auditor specialization. J Account Res 46(1):199–246

O’Keefe TB, Simunic DA, Stein MT (1994) The production of audit services: evidence from a major public accounting firm. J Account Res 32(2):241–261

o.V. (2009) Wirtschaftsprüfer bieten Dienste zu Kampfpreisen. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (16.09.2009):16

Palmrose Z-V (1986) The effect of nonaudit services on the pricing of audit services: further evidence. J Account Res 24(2):405–411

Petersen K, Zwirner C (2008) Angabepflichten der Honoraraufwendungen für den Abschlussprüfer—Theoretische und empirische Betrachtung der Offenlegungserfordernisse zur Stärkung der Prüferunabhängigkeit. Wirtschaftsprüfung 61(7):279–290

Quick R, Sattler M (2011a) Beeinträchtigen Beratungsleistungen die Urteilsfreiheit des Abschlussprüfers? Zum Einfluss von Beratungshonoraren auf diskretionäre Periodenabgrenzungen. Z Betriebswirtsch Forsch 63(6):310–343

Quick R, Sattler M (2011b) Das Erfordernis der Umsatzunabhängigkeit und die Konzentration auf dem deutschen Markt für Abschlussprüferleistungen. Z Betriebswirtsch 81(1):61–98

Quick R, Warming-Rasmussen B (2009) Auditor independence and the provision of non-audit services: perceptions by German investors. Int J Audit 13(2):141–162

Raghunandan K, Rama DV, Read WJ (2004) Local and regional audit firms and the market for SEC audits. Account Horiz 18(4):241–254

Salop SC (1979) Monopolistic competition with outside goods. Bell J Econ 10(1):141–156

Schmalensee R (1978) Entry deterrence in the ready-to-eat breakfast cereal industry. Bell J Econ 9(2):305–327

Simon DT (1985) The audit services market: additional empirical evidence. Audit J Pract Theory 5(1):71–78

Simons D, Zein N (2011) Audit market segmentation—the impact of mid-tier audit firms on competition. Working Paper, University of Mannheim

Simunic DA (1984) Auditing, consulting, and auditor independence. J Account Res 22(2):679–702

Stefani U (2006) Anbieterkonzentration bei Prüfungsmandaten börsennotierter Schweizer Aktiengesellschaften. Betriebswirtschaft 66(2):121–145

Weil J (2004) Auditing firms get back to what they do best. Wall Street Journal (31.03.2004):C3

Weil J (2005) In post-Enron world, accounting firms fight over the pieces. Wall Street Journal (18.03.2005):C1

Whisenant S, Sankaraguruswamy S, Raghunandan K (2003) Evidence on the joint determination of audit and non-audit fees. J Account Res 41(4):721–744

Wu MGH (2006) An economic analysis of audit and nonaudit services: the trade-off between competition crossovers and knowledge spillovers. Contemp Account Res 23(2):527–554

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bleibtreu, C., Stefani, U. Auditing, consulting, and audit market concentration. Z Betriebswirtsch 82 (Suppl 5), 41–70 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-012-0597-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-012-0597-5