Abstract

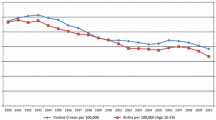

Urban communities in the United States were transformed at the end of the twentieth century by a rapid decline in neighborhood crime and violence. We leverage that sharp decline in violence to estimate the relationship between violent crime rates and racial disparities in birth outcomes. Combining birth certificate data from US counties with the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting statistics from 1992 to 2002, we show that lower crime rates are associated with substantially smaller Black-White disparities in birth weight, low birth weight, and small for gestational age. These associations are stronger in more segregated counties, suggesting that the impacts of the crime decline may have been concentrated in places with larger disparities in exposure to crime. We also estimate birth outcome disparities under the counterfactual that the crime decline did not occur and show that reductions in crime statistically explain between one-fifth and one-half of the overall reduction in Black-White birth weight, LBW, and SGA disparities that occurred during the 1990s. Drawing on recent literature showing that exposure to violent crime has negative causal effects on birth outcomes, which in turn influence life-course outcomes, we argue that these results suggest that changes in national crime rates have implications for urban health inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The birth certificate data from the National Center for Health Statistics(NCHS) were obtained through a restricted use data agreement. For more information on how to apply for restricted-usevital statistics data, see https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/nvss-restricted-data.htm

Notes

While the available official crime statistics are not suitable to make inferences on the extent to which certain neighborhoods and racial/ethnic groups experienced larger changes in violent crime, indirect pieces of evidence indicate that racial and ethnic minorities, particularly Black Americans, experienced the largest improvements in public safety in their communities. Similarly, self-reported data on victimization from the National Crime Victimization Survey shows that individuals in low-income households experienced larger relative and absolute declines in violent victimization, as compared to individuals in higher-income households [3].

Some have cautioned against the use of UCR county-level crime data [29] due to the inconsistencies in reporting patterns across large and small law enforcement agencies. In the appendix, we report results using only murders, which are less likely to be under-reported so the extent of measurement error is small. Results are similar to those reported in the main text.

Data from 1993 were not made public, so we impute 1993 values as the average of the 1992 and 1994 values. Results are not sensitive to the exclusion of 1993.

Multiple births are much more likely to be LBW, SGA, and preterm, and are therefore excluded.

Specifically, we estimated predicted birth outcome gaps using Stata’s margins command [31] by setting county-level violent crime rates in Model 3 at their 1992 level and allowing all other variables to trend as observed.

Coefficients, standard errors, and R-squared for Model Eq. 2 are reported in the appendix.

References

Blumstein A, Wallman J, editors. The crime drop in America. Revised. New York, NY: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2006.

Zimring FE. The great American crime decline. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Sharkey P. Uneasy peace: the great crime decline, the renewal of city life, and the next war on violence. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company; 2018.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime data explorer. Summary reporting system. 2021. http://www.ucrdatatool.gov. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Friedson M, Sharkey P. Violence and neighborhood disadvantage after the crime decline. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci. 2015;660(1):341–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716215579825. ISSN 15523349.

Peterson J. The feminization of poverty. J Econ Issues. 1987;21(1):329–37.

Peterson RD, Krivo LJ. Divergent social worlds: neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2010.

Torrats-Espinosa G. Crime and inequality in academic achievement across school districts in the United States. Demography. 2020;57(1):123–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00850-x. ISSN 15337790.

Sharkey P, Friedson M. The impact of the homicide decline on life expectancy of African American males. Demography. 2019;56(2):645–63.

Goin DE, Gomez AM, Farkas K, Zimmerman SC, Matthay EC, Ahern J. Exposure to community homicide during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a within-community matched design. Epidemiology. 2019;30(5):713–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000001044. ISSN 15315487.

Grossman D, Khalil U. Neighborhood crime and infant health. J Urban Econ. 2022:103457

Brown R. The mexican drug war and early-life health: the impact of violent crime on birth outcomes. Demography. 2018;55(1):319–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0639-2. ISSN 15337790.

Mansour H, Rees DI. Armed conflict and birth weight: evidence from the al-Aqsa Intifada. J Dev Econ. 2012;99(1):190–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.12.005. ISSN 03043878.

Torche F, Shwed U. The hidden costs of war: exposure to armed conflict and birth outcomes. Sociol Sci. 2015;2:558–81.

Ang D. The effects of police violence on inner-city students. Q J Econ. 2021;136(1):115–68.

Reichman NE. Low birth weight and school readiness. Futur Child. 2005;15(1):91–116. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2005.0008. ISSN 10548289.

Almond D, Chay KY, Lee DS. The costs of low birth weight. Q J Econ. (August) 2005.

Conley D, Strully KW, Bennett NG. The starting gate: birth weight and life chances. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003.

Aizer A, Currie J. The intergenerational transmission of inequality: maternal disadvantage and health at birth. Science. 2014;344(6186):856–61. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1251872. ISSN 10959203.

Van den Bergh BR, van den Heuvel MI, Lahti M, Braeken M, de Rooij SR, Entringer S, Hoyer D, Roseboom T, Räikkönen K, King S, et al. Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health: the influence of maternal stress in pregnancy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;117:26–64.

Mark NDE, Torrats-Espinosa G. Declining violence and improving birth outcomes in the us: evidence from birth certificate data. Soc Sci Med. 2022;294:114595.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Driscoll AK, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66(1):1–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374407-4.00228-4. ISSN 00836729.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Munson ML. Births: final data for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2003;52(10):1–113.

Torche F. The effect of maternal stress on birth outcomes: exploiting a natural experiment. Demography. 2011;48(4):1473–91.

Brown R. The Intergenerational impact of terror: did the 9/11 tragedy impact the initial human capital of the next generation? Demography. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00876-6. ISSN 15337790.

Mulder EJH, Robles De Medina PG, Huizink AC, Van Den Bergh BRH, Buitelaar JK, Visser GHA. Prenatal maternal stress: effects on pregnancy and the (unborn) child. Early Hum Dev. 2002;70(1–2):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-3782(02)00075-0. ISSN 03783782.

Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(4):601–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. ISSN 00332909.

Koppensteiner MF, Manacorda M. Violence and birth outcomes: evidence from homicides in Brazil. J Dev Econ. 2016;119:16–33.

Maltz MD, Targonski J. A note on the use of county-level UCR data. J Quant Criminol. 2002;18(3):297–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb046606. ISSN 00330337.

Talge NM, Mudd LM, Sikorskii A, Basso O. United States birth weight reference corrected for implausible gestational age estimates. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):844–53. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3285. ISSN 10984275.

Williams R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata Journal. 2012;12(2):308–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x1201200209. ISSN 1536867X.

Conley D, Bennett NG. Is biology destiny? Birth weight and life chances. Am Sociol Rev. 2000;65(3):458–67.

Behrman JR, Rosenzweig MR. Returns to birthweight. Rev Econ Stat. 2004;86(2):586–601.

Currie J, Moretti E. Biology as destiny? Short-and long-run determinants of intergenerational transmission of birth weight. J Labor Econ. 2007;25(2):231–64.

Royer H. Separated at girth: US twin estimates of the effects of birth weight. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2009;1(1):49–85.

Cheadle JE, Goosby BJ. Birth weight, cognitive development, and life chances: a comparison of siblings from childhood into early adulthood. Soc Sci Res. 2010;39(4):570–84.

Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ: Br Med J. 1990;301(6761):1111.

Dufault B, Klar N. The quality of modern cross-sectional ecologic studies: a bibliometric review. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(10):1101–7.

Acknowledgements

This project received no outside funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mark, N., Torrats-Espinosa, G. Exposure to Crime and Racial Birth Outcome Disparities. J Urban Health 101, 692–701 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-024-00864-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-024-00864-w

Keywords

Profiles

- Gerard Torrats-Espinosa View author profile