Abstract

Over the past decades, the number of single households is constantly rising in metropolitan regions. In addition, they became increasingly heterogeneous. In the media, individuals who live alone are sometimes still presented as deficient. Recent research, however, indicates a way more complex picture. Using the example of Vienna, this paper investigates the quality of life of different groups of single households in the city. Based on five waves of the Viennese Quality of Life Survey covering almost a quarter of a century (1995–2018), we analyse six domains of subjective well-being (satisfaction with the financial situation, the housing situation, the main activity, the family life, social contacts, and leisure time activities). Our analyses reveal that, in most domains, average satisfaction of single households has hardly changed over time. However, among those living alone satisfaction of senior people (60+) increased while satisfaction of younger people (below age 30) decreased. Increasing differences in satisfaction with main activity, housing, or financial situation reflect general societal developments on the Viennese labour and housing markets. The old clichéd images of the “young, reckless, happy single” and the “lonely, poor, dissatisfied senior single” reverse reality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Living alone is a growing trend in highly industrialized Western societies (DePaulo, 2006; Jamieson & Simpson, 2013; Klinenberg, 2012), in particular in metropolitan regions (Buzar et al., 2005; Chandler et al., 2004; Hall & Ogden, 2003). Induced by multiple changes in economic conditions as well as by the rise of individualization and post-materialist values (e.g., Hettlage, 2000; Lesthaeghe, 2010; Van de Kaa, 1987), individuals living alone experience several non-familial forms of life, somewhat detached from predefined biographies and disembedded from traditional family ties (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 2001). Since the 1960ies, single-person households are on a constant rise in Europe, from 5% in pre-industrial settlements, to 30–60% in contemporary European cities (Snell, 2017). Living alone has been for long subject of varying stereotypes (Greitemeyer, 2009). Thereby, characterisations of singles showed tremendous ambivalence, ranging from the “heroic single” as role model for a self-determined life to derogatory prejudices like the “old maid” (Hradil, 2003). Often, singles have been viewed as deficient, some views proclaiming that single individuals are risky, irresponsible, promiscuous, and/ or lonely (Conley & Collins, 2002; DePaulo, 2006; Hertel et al., 2007). Although the perception of single people has been changing (Kislev, 2019; Simpson, 2016), some stereotypes persist (Day, 2016; Slonim et al., 2015). They are still reflected in newspaper articles like ‘Single shaming: Why people jump to judge the un-partnered’ (Klein, 2022), ‘You don’t have to settle: the joy of living (and dying) alone’ (Goff, 2019) or ‘I’m 40 and chronically single. Is my unhappy childhood to blame?’ (Frostrup, 2018). The clichéd images of the “young, reckless, and happy male single” and the “lonely, poor, and dissatisfied old lady” may be the most extreme expressions of such stereotypes in cities. They do obviously not reflect realities in modern urban societies. As Adamczyk (2021: 163) recently mentioned, the “ambivalent evaluation of singlehood” makes it “extremely important” to gather and present “results of empirical research”. The present article aims to provide the respective empirical evidence.

The rare research on single people hardly ever supported such stereotypes (e.g., Greitemeyer, 2009; Hradil, 2003). Nevertheless, we do surprisingly still not know much about single households in cities and their quality of life. Maybe, living alone was once mainly a living arrangement of senior women who outlived their partners. However, today one can find male and female single households of all ages, including divorcees, couples living apart, or people who have never been in a relationship/ married. Single households comprise a very heterogeneous group of individuals with varying needs and expectations about their lives (Koropeckyj-Cox, 2005; Park et al., 2023). Nevertheless, quality of life research usually concentrates on comparing household forms (e.g., Blekesaune, 2018; Chang, 2013; Shapiro & Keyes, 2008; Vanassche et al., 2013). Only a few studies focus on the well-being of those who live alone (e.g., Apostolou et al., 2019; Kislev, 2019, 2021) but hardly any do so in the urban context (for an exception see Riederer et al., 2021a). Consequently, there is a need to explore the well-being of singles in contemporary Western cities, thereby particularly considering the increasing diversity of adults who live alone.

Against this background, the present paper contributes to painting a realistic and accurate picture about the well-being of singles in the city. Explicitly addressing the heterogeneity within the group of adults who live alone, we analyse developments of subjective well-being (SWB) of single households in Vienna between 1995 and 2018. Vienna experienced a significant increase and growing diversity in single households during the last decades. We base our empirical results on a unique data set (11,015 respondents living in single households), covering well-being of Viennese residents for almost a quarter of a century (1995, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018). Particularly focusing on differences by age and gender, we first present a descriptive overview—using various indicators such as socioeconomic status, living environment, or health status—to characterise selected groups of single-households. Second, we analyse how several domains of SWB have changed among those who live alone over time. Finally, we explain differences between varying groups of singles by their differing characteristics. To our knowledge, there is currently no other study analysing the well-being of different groups of single households (with respect to gender and age) in a multidimensional way.Footnote 1

Subjective Well-Being of Those Living Alone: Prior and Present Research

In the literature various definitions and concepts are used to describe single people, either referring (to a combination of or exclusively to) their living arrangement, their formal civil status, their romantic/ intimate attachment or relationship status (Adamczyk, 2021; Stein, 1976). In modern societies, singlehood is characterised by great heterogeneity (Koropeckyj-Cox, 2005; Park et al., 2023), each definition entailing specific pros and cons. Since there does not exist a unique established concept of singles, the definition should be strongly related to the central goal of the research question. Our specific interest concerns social change. The analysis of developments over almost a quarter of a century requires that measures are available at several points in time. Thus, in the present paper, we focus on single households in our empirical analyses (i.e. those living alone). Nevertheless, our literature review does not exclude studies employing other conceptualizations.

Previously, research on SWB of singles has strongly been influenced by the presumption that happiness is related to a romantic/ intimate partnership in the same household and therefore mostly examined singles whilst comparing them to coupled people (e.g., Dush & Amato, 2005; Stack & Eshleman, 1998; Ta et al., 2017; Vanassche et al., 2013). This is not surprising, since in human history the most acceptable form in which the course of human life took place was via participation in communities, of which the family was the most important group of social participation (Adamczyk, 2021). It has been argued that people living with a long-term partner are happier than those who do not (DePaulo & Morris, 2005; Diener et al., 2000), because relationships offer emotional support, facilitate coping with life stress, foster self-esteem (Overall et al., 2010), amplify positive accomplishments (Gable et al., 2004), offer embeddedness in networks of supportive and helpful others or even provide economic advantages through shared expenses in the same household (Ross et al., 1990; Waite, 1995). In line with this argument, some studies found that living alone is associated with lower life satisfaction, feelings of loneliness, or poorer psychological health (Dahlberg et al., 2022; Dush & Amato, 2005; Grundström et al., 2021; Helliwell, 2003; McCabe et al., 1996; Shapiro & Keyes, 2008).Footnote 2 However, stimulated by early criticism of psychologists (Boon, 2016; Clark & Graham, 2005; DePaulo & Morris, 2005; Shapiro & Keyes, 2008), scholars nowadays increasingly argue that these explanations of the “happiness gap” of singles suffer from oversimplification (Kislev, 2020; Oh et al., 2021). Single individuals are capable of investing in relationships outside the household (e.g., with siblings, parents or friends) from which they can derive happiness (Fisher et al., 2021; Park et al., 2021) or seize the opportunity for pursuing individual interests and career aspirations (DePaulo, 2006; Klinenberg, 2012). In addition, Girme et al. (2016: 126) showed that being single does not have to undermine happiness for individuals who strive to sustain close relationships by trying to avoid conflict and prevent negative relationship outcomes. Furthermore, findings of Apostolou et al. (2019) or Kislev (2021) suggest that SBW may only be impaired if individuals are involuntarily living alone (which is especially found among men). According to Kislev (2019), single people are even able to gain more happiness from a positive self-perception, socializing and occupational activities than married people. Other results indicate that socioeconomic characteristics of singles may be responsible for the “happiness gap”. For instance, Forward et al. (2021) most recently show that older women living alone do not share significant elevated risks for deprived wellbeing in the UK after controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors. Singles are a heterogeneous group and their SWB is multidimensional (Hradil, 2003; Kislev, 2021; Klinenberg, 2012; Ta et al., 2017). During the last decades, the composition of single households in Europe has changed especially with regard to gender and age.

Studies not focusing on singles proved that gender and age are both important determinants of SWB (Inglehart, 2002; Magee, 2015; Meisenberg & Woodley, 2015). Due to unequal access to resources and hierarchical societal positions, it is usually argued that women are not only less likely to meet their needs than men but do also feel less enabled to do so (e.g., Batz & Tay, 2018). In addition, women are more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms than men (Girgus et al., 2017; Kuehner, 2017). Therefore, women’s SWB should be lower than men’s SWB. However, the empirical evidence is contradictory. Some studies find lower levels of SWB among women (e.g., Gonzalez-Carrasco et al., 2017) and others among men (e.g., Graham & Chattopadhyay, 2013). The literature regarding age differences is inconclusive as well. It is commonly argued that SWB should decrease with age because one’s individual health diminishes substantially, including not only physical but also mental capabilities and social participation (Walker, 2005). Research on well-being in old age, however, points also to the ability of senior people to adapt to their circumstances (Lopez Ulloa et al., 2013). Charles and Carstensen (2009) even argue that individuals experience more life satisfaction with increasing age because, with shrinking future time horizons, they spend more time in activities that contribute to their current well-being. By contrast, younger people may often face a larger goal-achievement gap due to high hopes and expectations (Argyle, 2001). Although the risk of social isolation increases with age, loneliness affects life negatively at all ages and is not restricted to the elderly at all (Hämmig, 2019; Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016). Luhmann and Hawkley (2016) even report elevated loneliness levels among young adults. Overall, studies focusing on psychological outcomes and living alone also point towards a complex picture. Social and economic contexts and resources matter (Adamczyk, 2021; Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016; Ta et al., 2017). Several authors thus even emphasize the importance of drawing distinctions within the group of older adults living alone (Baumbusch, 2004; Djundeva et al., 2018) and of observing the psychological well-being of single individuals across several life domains (Ta et al., 2017).

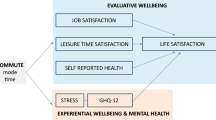

This summary of prior research underlines that there is a specific “need for more in-depth research […] of life satisfaction among diverse groups of single adults” (Stahnke & Cooley, 2020:1). We thus analyse the SWB of single women and men of different ages (below 30, age 30–59, and age 60 and above). Acknowledging the multidimensionality of SWB—which is emphasized in many major contributions of quality of life research (e.g., Allardt, 1976; Campbell et al., 1976; Diener, 2009; Veenhoven, 2000), we analyse the subjective satisfaction with six different life domains: the financial situation, the housing situation, the main activity, the family life, social contacts, and leisure time activities. Proceeding from the assumptions that SWB is dependent on an individual’s needs and the material, personal, and social resources allowing to fulfil them, and that people differ with respect to both needs and resources, we reason that groups of singles will differ in various domains of their SWB. In particular, we assume that their resources will affect the degree to which they are able to bear the costs and to enjoy the benefits of living alone (Matsuura & Ma, 2021).

The city of Vienna is a great example to analyse the urban phenomenon of single households: First, Vienna experienced an increase in single households during the last decades, in particular among the working age population. Today, there are more than 400,000 single households in Vienna, corresponding to 44% of all private households and 22% of all residents (Statistics Austria, 2021d). Second, the share of singles is comparatively large even with respect to other European cities (e.g., 21% in Brussels, 19% in Stockholm, 18% in Rome, 17% in Paris)Footnote 3 (Eurostat 2019). Third, processes of demographic rejuvenation and ageing are also important developments in Vienna (MA23, 2014). The Viennese population is growing due to both national and international immigration (37% foreign-born in 2020; Statistics Austria, 2021a), changing and challenging the city in particular with regard to housing, labour market, and social inequality issues (cf. Kazepov & Verwiebe, 2021). These processes also affect life circumstances of (young) singles.

In Vienna, living alone was once largely characterized by senior female widows who lost their partners. In 1971, 53% of all single households were women aged 60+ (Fig. 1). Until 2020, this figure decreased to 26%. Within this time period, the share of younger age groups and men increased. For instance, the share of men between 30 and 59 increased from 9 to 27% (Fig. 1). Living alone became more widespread among most observed groups (Appendix Fig. A1), resulting in a peak of heterogeneous single life in the city of Vienna. In the next section, we discuss potential effects of social change in the context of Viennese trends on several distinct domains of SWB, considering differences in resources among people who live alone. Thereby, we focus on developments in Vienna during the last decades as they provide the background for changes in SWB. As not only the composition of single households has changed over time, but also their life circumstances, we have to consider multiple developments that had consequences for SWB in Vienna in general, and single households in particular. Taking the heterogeneity of single households into account, we develop assumptions about age and gender differences in SWB among single households.

Share of age groups within single households. Note: Single households are one-person households. Source: Statistics Austria (2021d), Population Census or Microcensus Labour Force Survey / Housing Survey (own calculations)

Single Households’ SWB in Vienna: Developments and Differences by Age and Gender?

A number of significant changes occurred on the labour market, influencing the individual (satisfaction with the) financial situation as well as the employment status. The trend towards more flexibilization (Fritsch & Verwiebe, 2018; Verwiebe & Fritsch, 2011; Verwiebe et al., 2019) was driven by rising economic competition due to processes of globalization and the optimization of value-added chains, the growth of the service sector, but also by government-initiated programmes aimed at reducing mass unemployment after the financial crises in 2008/09 (Hermann & Flecker, 2012). Despite these government programmes, there were increases in the unemployment rate and receipt of means-tested guaranteed minimum income in Vienna until 2017 (Riederer et al., 2021b; Statistics Austria, 2021c). Although lagged compared to other European countries, we also observe growing numbers of precarious atypical employment relationships in Austria, especially in Vienna (Fritsch et al., 2020; Teitzer et al., 2014; Verwiebe et al., 2013). Risks of working in temporary employment, part-time, and poorly paid jobs are significantly pronounced among younger employees and/or women (Fritsch et al., 2019; Riederer et al., 2021b). Although younger people ‒ and especially young women ‒ are, on average, much better educated than former generations, they are increasingly at risk of being on the margins of the labour market or facing unemployment (Fritsch, 2014). In addition, female disadvantages on the labour market (Fritsch, 2018; Riederer & Berghammer, 2020) have also negative medium and long term consequences, resulting in pronounced poverty risks—especially of divorced women (in advanced age).

Further, Vienna’s population growth and the recent rise in single households have also created new pressures in terms of affordable housing—especially for younger singles in unemployment, education, or precarious low-paid jobs (Arbeiterkammer Wien, 2014; Bennett & Dixon, 2006). Thus, young singles may face additional disadvantages in terms of affordable housing because social housing programs (“Sozialer Wohnbau”) tend to favour individuals fully integrated into the labour market with steady incomes (Reinprecht, 2017). In contrast, many senior residents enjoy nice living environments, benefitting from long-standing housing arrangements in attractive neighbourhoods, pre-existing cheaper rent contracts, or higher financial assets to afford high-quality housing (Litschauer & Friesenecker, 2021). For instance, the share of senior people is higher in the Western areas of Vienna that are largely characterised by higher quality of life (Troger & Gielge, 2016). In addition, living arrangements of senior residents received considerable policy attention in Vienna in the past years as a decline in available family support needs to be counteracted by subsidies (Wohnservice Wien, 2019).

Social contacts to family, colleagues, and friends are highly important for single people’s well-being (Djundeva et al., 2018; Kislev, 2019). Social life and leisure activities of seniors can be impaired after retirement or the death of close family members and friends. In particular, the loss of the partner can lead to severe feelings of loneliness (Dahlberg et al., 2022). However, staying socially attached may be easier for some and harder for others, depending on physical mobility and health, financial means and employment status, and other material and social resources. In addition, social life is different nowadays than twenty years ago, when smartphones or applications like Facebook, Instagram, or Tinder did not exist. Meanwhile, social media and new forms of networking reshaped our personal lifestyle, social relationships, and leisure activities (Leung & Lee, 2005). The literature on the ‘grey digital divide’ (e.g., Millward, 2003) noted that seniors sometimes find it difficult to keep up with the new technologies, which can enhance loneliness and social isolation (Roblek, 2019). But many seniors are able to maintain their social connections with peers or compensate lost social contacts by sharing (more) quality time with selected people, often including children and grandchildren (e.g., Djundeva et al., 2018; Forward et al., 2021; Hogan et al., 2016). The city of Vienna also increasingly supports activities enabling senior citizens to benefit from new possibilities, including programmes to facilitate communication and to organize group activities among them (cf. www.digitalcity.wien). For younger individuals, participating in the online world may be more natural. But social media consumption also involves certain risks: it is often time consuming as well as less favouring to close relationships and strong ties (Leung & Lee, 2005), it produces high opportunity costs (due to missed other leisure activities) and may lead to high levels of stress and frustration (due to the “fear of missing out” (Blachino & Przepiorka, 2018) or feelings of “negative comparisons” (Frison & Eggermont, 2016)). Therefore, conclusions about age differences of single people in satisfaction with one’s social life are not straightforward.

Similarly, assumptions about gender differentials are hardly possible: Women may be better socializers than men or exchange more often with children and grandchildren (Hank & Buber, 2009). However, women may also suffer more from societal pressures regarding their status of living alone. Although living alone is widespread among young people nowadays, stereotypes that single women are less caring and have lower interpersonal skills still persist (Day, 2016; Greitemeyer, 2009; Hertel et al., 2007; Kislev, 2019; Slonim et al., 2015). Gender differences may also result from separation and divorce. In Vienna, the divorce rate amounted already to approximately 50% in the second half of the 1990ies and increased to 66% in 2006, before steadily declining to 44% in 2019 (Statistics Austria, 2021b). As already discussed above, divorce may lead to poverty among women. Male disadvantages after divorce, usually referring to declining social integration and feelings of loneliness, are often temporary (Leopold, 2018).

Based on these recent developments (in Vienna), several assumptions about age and gender differentials in SWB among single households are plausible: Younger singles could be disadvantaged in their financial situation and main activity. This age gap is likely to have grown in the last decades. Moreover, women are generally disadvantaged on both the labour market (e.g., lower income, income losses after divorce) and the housing market. In addition, the weaker economic position of younger people (compared to seniors) as well as women (compared to men) may also restrict their opportunities regarding leisure activities and, thereby, impair their socializing. Altogether, it seems straightforward to hypothesize that young singles and female singles lost in terms of material well-being (e.g., financial situation, housing) compared to senior singles and male singles, respectively. In stark contrast, however, age and gender differences in satisfaction with domains of social life (e.g., family, leisure) are hardly predictable.

Data and Methods

Our analysis is based on a unique data set, which resulted from research collaborations of the University of Vienna and the City of Vienna. Between 1995 and 2018, data on living arrangements, living conditions, family issues, personal relationships, labour market behaviour, quality of life, health, or happiness have been collected in five cross-sectional surveys (each covering between 8,066 and 8,704 respondents). Methods of data collection comprised face-to-face interviews (1995–2008), computer assisted telephone interviews (random digit dialling, 2003–2018), and computer assisted web interviews (2018). The data is representative for the population of Vienna (age 15 years and above). The subsample for our analyses comprises 11,015 respondents living in single households (between 1,785 and 2,535 respondents each wave). Weights adjust for the variation in the selection probabilities of households and districts (design weights), for age, gender, education, district, and type of housing (post-stratification weights) and, in 2018, for mode effects.

Measures of SWB comprise the satisfaction with housing (apartment or house), the satisfaction with the households’ financial situation, and the satisfaction with the respondents’ main activity (professional work, education or training, household labour etc.), the satisfaction with the family situation, the satisfaction with social contacts (friends, acquaintances etc.), and the satisfaction with time for leisure activities (e.g., cultural activities, sport activities, meeting friends).Footnote 4 Respondents could assess their satisfaction in different domains on 5-point rating scales, ranging from 1 (very satisfied) to 5 (not satisfied at all). In the Results section, we present the share of respondents who are very satisfied or satisfied (values 1 and 2).

Some analyses for 2003 and/or 2018 include indicators for private life, health, socioeconomic characteristics, living environment, employment status, and personality/lifestyle. For 2018, measures are the following: Private life is assessed by three variables that refer to partnership status: (a) partner (romantic relationship: no/yes), (b) married (no/yes), (c) divorced or widowed (no/yes). Indicators for health comprise questions covering the degree of physical impairments (no/yes; if yes: severe limitations, some limitations, no limitations in daily life) and psychological well-being (pessimism regarding the own future).Footnote 5 Socioeconomic characteristics refer to tertiary education (no/yes), citizenship (Austrian or other), and household income (max. € 910 per month or more). The living environment is covered by city area (eight categories)Footnote 6 and living space (max. 55 square meters or more). Employment status distinguishes between respondents who are in education or training, employed, unemployed, retired, or other (non-employed or unknown). Analyses including 2003 cannot build upon such detailed information. Measures indicating city area or personality/lifestyle had to be omitted. Other aspects have been assessed slightly different: Regarding private life, we can only assess being married, divorced, or widowed. For health, we employ an indicator of subjective health, comparing those who reported “very good health” (value 1 on a five-point rating scale) to others. Migrant background is assumed if the respondent or at least one of its parents has been born abroad. For income, we distinguish between those belonging to the lowest quartile of equivalised household income and others to allow for meaningful comparisons over time.

Our analytical strategy comprises several steps: First, we will give a short description of the characteristics of single households in Vienna. Second, we describe the development of SWB of persons living in single households over time. Third, we analyse differences in SWB between the young and the senior group of single households in Vienna. Therefore, we conduct stepwise regression analyses to draw conclusions about the importance of differences in life circumstances—i.e. private life, health, socioeconomic characteristics, living environment, employment status, and personality/lifestyle (cf. Table 1)—for differences in domain satisfactions between the distinguished groups of single households. Based on binomial logistic regressions, we estimate average marginal effects because these are the most likely to be comparable across different models (Mood, 2010) and use the KHB method (Karlson et al., 2012) to examine whether differences in life circumstances account for the observed differences in satisfaction between single-household types. Next, the same methods are applied to analyse differences in SWB between survey waves (i.e. changes over time). In this case, life circumstances are restricted to the characteristics shown in Table 2. Finally, complementary analyses link domain satisfaction with overall assessments of life satisfaction (see Appendix, part II).

Results

Changes in Characteristics of Single Households

To begin with, we want to examine who makes up the group of singles in Vienna. Thus, Table 1 characterises those living alone in 2018. Findings confirm the great heterogeneity of single households’ life circumstances (e.g., Esteve et al., 2020; Koropeckyj-Cox, 2005; Piekut, 2020). For instance, within the subgroup of senior men (aged 60+) we observe small shares of people receiving low incomes and living in undersized flats (36% compared to 66% in the age group < 30 years), making it also more likely that they show great satisfaction with their housing or financial situation. In contrast, the majority of singles below the age of thirty lives in flats smaller than 55 square meters (young female singles 73%; young male singles 66%), one in five singles below 30 years is still in education, and unemployment is also slightly higher in this age group than in others. Non-Austrian citizenship is far more prevalent among young men who live in single households (young female singles 10%; young male singles 18%). This holds both for the advantaged group of EU migrants as well as the usually disadvantaged group of third country citizens (Riederer et al., 2021a; Riederer et al., 2019). Geographically, single households are spread across all city areas. Nevertheless, young single women are overrepresented at the affordable “Western belt” (10% at the Western belt, northern part and 17% at the Western belt, southern part) and young single men in the traditionally working-class South-East (32% in 2018) whereas both young single women and men are underrepresented in the green and family-friendly/suburban North-East of Vienna.

Table 1 also indicates that senior singles are confronted with some specific disadvantages (e.g., Piekut, 2020; Walker, 2005). Regarding health, for instance, senior age groups are more often severely impaired than younger ones (senior female singles 13%, senior male singles 9%). In addition, almost 80% of singles at age sixty or above have experienced the loss of a partner, either due to divorce or death. In particular, almost half of the women of this group are widows. Nevertheless, put differently, only 14% of the senior women have never been married whereas 97% of the singles below thirty have never been. Personality and lifestyle attitudes also vary among single households in 2018: For the young (in particular men), trying out new things and having fun is more important whereas the senior group (in particular women) emphasize modesty and conscientiousness.

In addition, we find a number of interesting developments over time (Table 2): First, the senior group of singles are less often widowed but more often divorced in 2018 than in 2003. Second, subjective health ratings interestingly suggest that the health of the young singles may have deteriorated (e.g., 53% with very good health among young female singles in 2003 and 29% in 2018). Third, more of those who live alone have a migrant background nowadays than in the past; in particular among the young singles (difference of 12–13 ppt between 2003 and 2018). Fourth, despite their higher educational level, larger shares of the young are unemployed and live in small apartments than fifteen years ago. Overall, it seems that young single households have become more disadvantaged over time whereas the situation of seniors who live alone has hardly changed or even improved. For instance, senior single-women are more often tertiary educated, belong less often to the low-income group, and live less often in small apartments than in the past.

SWB of Different Groups of Single Households Over Time

Next, we examine changes in average SWB across several life domains over time and compare them across subgroups of single households to disentangle the layered nature of SWB and explore the likely diverging developments between different types of single households. Overall, we find pronounced age differentials: Among those living alone, (a) senior people (60+) are most satisfied with their housing; (b) younger people (< 30 years) are least satisfied with their financial situation; (c) men between 30 and 59 years are least satisfied with their family situation; and (d) both younger and senior people are more satisfied with their leisure time (see Table 3). These findings are very consistent over time (1995–2018 or 2003–2018). However, we can also observe relevant changes: Most interesting, both younger and senior singles were highly satisfied with their main activity in 2003 (averaging around 80–85%). In recent years, we do not find these high levels of satisfaction with regard to their main activity among the younger age groups anymore (only 66% of young female and 62% of young male singles highly satisfied) as conditions on the Viennese labour market have become more difficult (Fritsch et al., 2020; Riederer et al., 2021b). In addition, young women and men living alone have shown the highest levels of satisfaction with their family situation, social contacts, and leisure time in the past. Nowadays, senior singles are more satisfied with their social life than singles below age 30.Footnote 7 Given the improved health, mobility, and financial resources of Viennese seniors nowadays (Verwiebe et al., 2020), this group may be more and more able to uphold social participation and enjoy the advantages of living alone (Baeriswyl & Oris, 2021; Levine & Crimmins, 2018; Sanderson & Scherbov, 2015).

In Table 4, we show age differentials in SWB, alternately including varying explanatory variables reflecting differences in social and material resources that could be crucial for one or more dimensions of SWB (Gonzalez-Carrasco et al., 2017; Lopez Ulloa et al., 2013; Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016). In particular, we are interested whether aspects like having a partner, health, income, living environment, employment status, or lifestyle are responsible for age differences in SWB (covariates have been shown in Table 1). Results demonstrate that differences in social and material resources matter for age differentials in almost all observed dimensions of SWB: First, estimations indicate that higher satisfaction with the housing situation among the senior singles in 2018 can be partly explained by advantages in socioeconomic characteristics and the living environment (cf. M1 and M6-M8 in Table 4). If the observed social and material resources would be the same across age groups, the difference in housing satisfaction would drop from 19 to 10 ppt (cf. M1 and M9). Second, findings regarding satisfaction with the financial situation show even a reduction from 27 to 15 ppt if resources are considered. Third, although weaker in size, comparable results are found in domain satisfactions referring to the main activity and social contacts. This means that education, income, living space, and the living environment (i.e. city area) are not only relevant predictors for SWB but explain differences in these four domain satisfactions between age groups (albeit to a varying degree). Fourth, these predictors also contribute to age differentials in satisfaction with family life (cf. M1 and M8). However, aspects of private life and health counteract them, leading to larger predicted differences between age groups (see M2-M3 and M9-M11). This indicates that, if seniors would have the same health and family constellation than the younger persons, they would be more satisfied and, correspondingly, their advantage in SWB would be even larger. Although most relevant regarding satisfaction with family life, this is partly also observable for the other dimensions (M2-M3), in particular for social contacts, main activity, and financial situation. This may demonstrate the ability of senior people to adapt to their circumstances (Charles & Carstensen, 2009; Lopez Ulloa et al., 2013) or indicate disappointment of younger persons not achieving their aims in times of social media (Argyle, 2001; Blachino & Przepiorka, 2018; Frison & Eggermont, 2016). Fifth, employment status is most relevant for age differentials in satisfaction with leisure time because retired individuals are most satisfied with their leisure time. Sixth, personality and lifestyle attitudes hardly contribute to age differentials in SWB. They have only a minor effect on age differentials in satisfaction with leisure time (see M5). Finally, controlling for gender and survey method (M10-M11) does not alter our conclusions.Footnote 8

Focusing on changes over time, the lower satisfaction among young singles in 2018 than in 2003 is partly explained by changing life circumstances (Appendix Table A2). The singles below age 30 feel less healthy nowadays and this is associated with lower satisfaction in all observed six life domains. Higher unemployment in 2018 impaired the satisfaction with main activity and finances. Changes in socioeconomic status and living arrangements (i.e. higher shares of young singles with low income and small apartments) contributed to the decrease in satisfaction with social contacts. Overall, our findings emphasize the relevance of socioeconomic characteristics for single households’ SWB. However, neither the age differential in 2018 (Table 4) nor the decrease in SWB among young singles between 2003 and 2018 (Table A2) could be fully explained by considered life circumstances. In particular, age differentials in satisfaction with social life and decreasing satisfaction with leisure time among young persons living alone remain largely unexplained by our models. We can only speculate, but emerging social media may provide many challenges for young people (Blachino & Przepiorka, 2018; Frison & Eggermont, 2016).

Finally, we conducted a series of supplementary analyses demonstrating that changes in domain satisfactions also affected life satisfaction of single households (cf. Appendix, Part II). In general, trends in life satisfaction among subgroups of single households are in line with described changes in domain satisfactions. In particular, life satisfaction decreased among singles at younger ages. Decomposition analyses suggest that decreases in all six domain satisfactions contributed to decreasing life satisfaction among young women. Satisfaction with social contacts mattered most, followed by satisfaction with leisure time, family life, and (after 2008) finances. Most domain satisfactions had also an effect on the decreasing life satisfaction among young men (after 2013). But for young men, satisfaction with the main activity mattered most, followed by satisfaction with finances, family, and social contacts. According to additional decomposition models, the significant age differential in life satisfaction in 2018 is mainly explained by higher satisfaction with housing and finances among the 60 + age group. These findings both complement and confirm our prior findings: We observe a decrease in SWB of singles below age 30. In particular, for young women, decreasing satisfaction with social life is decisive whereas for young men, worsening satisfaction with economic aspects matter most. The higher satisfaction of senior singles in all observed domain satisfactions is reflected in higher satisfaction with life as a whole. As differences in socioeconomic characteristics (e.g., income) and living environment (i.e., dwelling size, city area) contribute most to explain age differentials in domain satisfactions, it is also not surprising that satisfaction with housing and finances are central to the difference between single households in life satisfaction.

Discussion

Even though living arrangements became noticeably diverse in the past decades, living alone is sometimes still subject to stereotypes (Goff, 2019; Greitemeyer, 2009; Kislev, 2019). However, especially psychological research tells us that popular and scientific images of singles suffer from oversimplification (cf. Adamczyk, 2016; Boon, 2016; Fisher et al., 2021; Girme et al., 2016; Park et al., 2023). They emphasise that it is “extremely important” to present reliable findings of scientific research (Adamczyk, 2021: 163), and that comparisons across several life domains are necessary to understand the SWB of the heterogeneous group of those living alone (Ta et al., 2017). Our study contributes to the literature in multiple ways. First, we complemented the limited literature on well-being of singles in the urban context. In the light of urban specifics, Vienna is an interesting case study to examine the increasing heterogeneity of single households and well-being differentials within the group of living-alone individuals. Therefore, we used a unique and large representative dataset. Second, we painted a realistic and accurate picture of the SWB of single households in the city by considering different life domains and their association with general life satisfaction. Third, going beyond previous research, we examined dynamics of SWB among single households over almost a quarter of a century.

Our findings demonstrate that, when looking at trends in SWB among persons living alone, it is highly relevant to consider the increasing heterogeneity of single households. The changing composition of single households in modern societies entails diversified levels and trends of SWB. We found that the SWB of senior individuals (aged 60+) has clearly improved, due to both increases in economic and social well-being. On the flipside, the group of young singles in Vienna experienced losses in social well-being as well as with regard to their labour market and housing situation. Consistent with our expectations and previous research in this field (Forward et al., 2021; Sandström & Karlsson, 2019), differences in socioeconomic background (e.g., income, available living space, or city area of residence) account for disadvantages of young people in many life domains. Financial restrictions, for instance, partly also explain lower satisfaction with social contacts or leisure activities.

From a broader perspective, our study suggests that greater individual freedom by living alone or the further spread of single households have not generally led to increasing levels of SWB among those who are living alone. Furthermore, our results emphasized the great importance of both the individual as well as the societal context (Adamczyk, 2021; Esteve et al., 2020; Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016; Ta et al., 2017). In particular, our results point to the conclusion that young people in single households in Vienna have become less satisfied due to increasing flexibility and insecurity on the labour market and the housing market (Fritsch et al., 2020; Riederer et al., 2021b). In contrast to developments of economic well-being, it may be surprising that senior individuals who live alone are better off in terms of social well-being than young individuals who live alone. But research has repeatedly shown that problems often associated with senior singles are relevant to the youth as well (e.g., loneliness; cf. Hämmig, 2019; Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016). Furthermore, seniors who are healthier nowadays than in the past may also share more quality time with remaining peers and family and may be more active in their leisure time (Fisher et al., 2021; Sanderson & Scherbov, 2015). Nevertheless, the observed decrease in social well-being among young Viennese women (below age 30) remains somewhat puzzling. Future research is needed to fully explain this development. At this point, we can only speculate that multiple pressures on solo-living young women may have contributed to this finding. Psychological research offers potential explanations: For instance, the trend of emerging social media (Blachino & Przepiorka, 2018; Frison & Eggermont, 2016) or societal expectations regarding professional careers and parenthood (Koropeckyj-Cox et al., 2007; Wilkinson & Rouse, 2022) could have increased social pressure, in particular for young women.

Our study is limited by using cross-sectional data of single households in one European city. First, there is an obvious need for panel studies allowing for causal inferences to examine effects of living alone on several dimensions on SWB. For instance, our results consistently indicate that differences in objective material circumstances are responsible for age differentials in satisfaction with housing or the financial situation. Yet, we cannot (and do not want to) rule out adaption effects and thus smaller goal-achievement gaps among senior people who live alone (Argyle, 2001; Lopez Ulloa et al., 2013). Second, our analyses refer to the specific case of Vienna. Thus, elevated or lower levels of subjective well-being do not necessarily have to be found in other societal contexts. Nevertheless, our research clearly demonstrates that the social and economic context is highly relevant to explain differentials in SWB of single households. From a societal perspective, it is important to emphasize that, as in previous studies on singles, existing stereotypes have not been supported by our findings (e.g., Greitemeyer, 2009; Hradil, 2003). To put it pointedly: If any generalized pictures about singles are possible at all, it would make more sense to replace the clichéd images of the “young, reckless, and happy male single” and the “lonely, poor, and dissatisfied old lady” by those of unhappy young and happy senior singles. In general, we showed that it is worth to analyse the SWB of single households in more detail to account for the great dynamics within this demographic group in past decades.

Notes

Additionally, it is not always entirely clear whether people are happier as a result of marriage or happier people are choosing to get married (e.g., Carr & Springer, 2010).

Data in text refers to 2015 to 2017. Outliers are Madrid (12%) or Berlin (31% in 2012). Figures refer to the population that lives in private households. Institutional households are excluded.

In additional analyses in the Appendix, we also consider the satisfaction with the individual life situation as a whole.

Respondents have been asked if they expect their life situation in general to change within the next ten years, and whether it will significantly improve, somewhat improve, stay more or less the same, somewhat deteriorate, or significantly deteriorate. The latter two options were classified as a pessimistic outlook on life. This is based on a self-rated health measurement (see Präg et al., 2022).

The variable city area distinguishes geographic regions. The inner regions of the city are surrounded by the u-shaped “belt” (Gürtel), a multilane road characterised by large traffic flows, in the North, the East, and the South. Many areas around the belt show above average shares of low-quality housing and lack green space. In general, peripheral residential areas in the North-West of the city are perceived to be of higher quality than areas in the South with its traditional working-class districts (see Troger and Gielge (2016) or Kazepov and Verwiebe (2021)).

Although most trends are also found in the total population and the “non-single population” (i.e. those living in households with at least two residents), they are more pronounced among single households (see Table A1).

Due to low case numbers, we did not differentiate single households by gender. Instead, we controlled for gender in model M10. In analyses with gender as sole control variable, gender had no significant effect on age differences in most domain satisfactions. Only regarding satisfaction with family life, the age difference was reduced by 1 ppt. In sensitivity analyses, we also control for method (web or telephone interview) because web interviews led to lower satisfaction scores. This affects all domain satisfactions but not our conclusions. Age differences are particularly reduced with regard to satisfaction with housing (by 4 ppt compared to M1 and 2 ppt compared to M10) and social contacts (by 3 and 2 ppt, respectively).

References

Adamczyk, K. (2016). An investigation of loneliness and perceived social support among single and partnered young adults. Current Psychology, 35(2016), 674–689.

Adamczyk, K. (2021). Current and future Paths in Research on Singlehood. In R. Coplan, J. Bowker, & L. Nelson (Eds.), The handbook of Solitude. Wiley-Blackwell.

Allardt, E. (1976). Dimensions of welfare in a comparative scandinavian study. Acta Sociol, 19(3), 227–239.

Apostolou, M., Matogian, I., Koskeridou, G., Shialos, M., & Georgiadou, P. (2019). The price of singlehood: assessing the impact of involuntary singlehood on emotions and life satisfaction. Evolutionary Pschological Science, 5(2019), 416–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-019-00199-9

Arbeiterkammer Wien. (2014). Wohnkostenbelastung junger ArbeitnehmerInnen in Wien. AK.

Argyle, M. (2001). The psychology of happiness. Routledge.

Baeriswyl, M., & Oris, M. (2021). Social participation and life satisfaction among older adults: Diversity of practices and social inequality in Switzerland. Ageing & Society. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001057

Batz, C., & Tay, L. (2018). Gender differences in subjective well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of Well-being (pp. 382–396). UT:DEF Publishers.

Baumbusch, J. (2004). Unclaimed treasures: Older women’s reflections on lifelong singlehood. Journal of Women & Aging, 16(1–2), 105–121.

Beck, U., & Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2001). Individualization: Institutionalized individualism and its social and political consequences. Sage.

Bennett, J., & Dixon, M. (2006). Single person households and social policy: looking forwards. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Blachino, A., & Przepiorka, A. (2018). Facebook intrusion, fear of missing out, narcissim, and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Research, 259, 514–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.012

Blekesaune, M. (2018). Is cohabitation as good as marriage for people’s subjective well-being? Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(2), 505–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9834-x

Boon, S. (2016). Special section preface. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(3), 344–347.

Buzar, S., Ogden, P., & Hall, R. (2005). Households matter: The quiet demography of urban transformation. Progress in Human Geography, 29(4), 413–436. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132505ph558oa

Campbell, A., Converse, P., & Rogers, W. (1976). The quality of American Life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. Russell Sage Foundation.

Carr, D., & Springer, K. (2010). Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 743–761.

Chandler, J., Williams, M., Maconachie, M., Collett, T., & Dodgeon, B. (2004). Living alone: Its place in Household formation and change. Sociological Research Online, 9(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.971

Chang, W.-C. (2013). Family ties, living arrangement, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(1), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9325-7

Charles, S., & Carstensen, L. (2009). Socioemotional selectivity theory. In H. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships (pp. 1579–1581). Sage Publications.

Clark, M., & Graham, S. (2005). Do relationship researchers neglect singles? Can we do better? Psychological Inquiry, 16(2–3), 131–136.

Conley, T., & Collins, B. (2002). Gender, relationship status, and stereotyping about sexual risk. Personality and Social Psychology Bullentin, 28(11), 1483–1494.

Dahlberg, L., McKee, K. J., Frank, A., & Naseer, M. (2022). A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 26(2), 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1876638

Day, M. (2016). Why people defend relationship ideology. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(3), 348–360.

DePaulo, B. M. (2006). Singled out: How singles are stereotyped, stigmatized, and ignored, and still live happily ever after. St. Martin’s Press.

DePaulo, B. M., & Morris, W. L. (2005). Singles in society and in science. Psychological Inquiry, 16(1/3), 57–83.

Diener, E. (2009). Assessing well-being. Springer.

Diener, E., Gohm, C., Suh, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Similarity of the relations between marital status and subjective well-being across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(4), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022100031004001

Djundeva, M., Dykstra, P., & Fokkema, T. (2018). Is living alone “aging alone”? Solitary living, network types, and well-being. The Journals of Gerontology, 74(8), 1406–1415.

Dush, C. K., & Amato, P. (2005). Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(5), 607–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505056438

Esteve, A., Reher, D., Trevino, R., Zueras, P., & Turu, A. (2020). Living alone over the life course: cross-national variations on an emerging issue. Population and Development Review, 46(1), 169–189.

Eurostat. (2019). Living conditions - cities and greater cities. Retrieved Accessed 23 May 2019. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=urbclivcon&lang=en

Fisher, A., Stinson, D. A., Wood, J., Holmes, J., & Cameron, J. (2021). Singlehood and attunement of self-esteem to friendships. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(7), 1326–1334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620988460

Forward, C., Khan, H., Fox, P., & Usher, L. (2021). The health and wellbeing of older women living alone in the UK: Is living alone a risk factor for poorer health? Ageing International, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-021-09426-w

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). "Harder, better, faster, stronger”: negative comparison on Facebook and adolescents’ life satisfaction are reciprocally related. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(3), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0296

Fritsch, N.-S. (2014). Warum Wissenschaftlicherinnen die Universität verlassen. SWS-Rundschau, 54(2), 159–180.

Fritsch, N.-S. (2018). Arbeitsmarkt, Berufe und Geschlecht in Österreich. SWS-Rundschau, 58(3), 307–327.

Fritsch, N.-S., & Verwiebe, R. (2018). Labor market flexibilization and in-work poverty: A comparative analysis of Germany, Austria and Switzerland. In H. Lohmann & I. Marx (Eds.), Handbook on In-work poverty (pp. 297–311). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Fritsch, N.-S., Verwiebe, R., & Liedl, B. (2019). Declining gender differences in low-wage employment in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Comparative Sociology, 18(4), 449–488.

Fritsch, N.-S., Liedl, B., & Paulinger, G. (2020). Horizontal and vertical labour market movements in Austria: Do occupational transitions take women across gendered lines? Current Sociology, online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120969767

Frostrup, M. (2018). I’m 40 and chronically single. Is my unhappy childhood to blame? The Guardian.

Gable, S., Reis, H., Impett, E., & Asher, E. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228

Girgus, J., Yang, K., & Ferri, C. (2017). The gender difference in depression: are elderly women at greater risk for depression than elderly men? Geriactrics, 2(4), 35-doi. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics2040035

Girme, Y., Overall, N., & Faingataa, S. (2016). Happily single: the link between relationship status and well-being depends on avoidance and approach social goals. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615599828

Goff, K. (2019). You don’t have to settle: The joy of living (and dying) alone. The Guardian.

Gonzalez-Carrasco, M., Casas, F., Malo, S., Vinas, F., & Dinisman, T. (2017). Changes with age in subjective well-being through the adolescent years: Differences by gender. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(1), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9717-1

Graham, C., & Chattopadhyay, S. (2013). Gender and well-being around the world. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1(2), 212–232.

Greitemeyer, T. (2009). Stereotypes of singles: Are singles what we think? European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(3), 368–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.542

Grundström, J., Konttinen, H., Berg, N., & Kiviruusu, O. (2021). Associations between relationship status and mental well-being in different life phases from young to middle adulthood. SSM- Population Health, 14(2021), 110774.

Hall, R., & Ogden, P. (2003). The rise of living alone in Inner London: Trends among the population of working age. Environment and Planning, 35(5), 871–888. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3549

Hämmig, O. (2019). Health risks associated with social isolation in general and in young, middle and old age. PLoS One, 14(7), e0219663. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219663

Hank, K., & Buber, I. (2009). Grandparents caring for their grandchildren: findings from the 2004 survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe. Journal of Family Issues, 30(1), 53–73.

Helliwell, J. (2003). How’s life? Combining individual and national variables explain subjective well-being. Economic Modelling, 20(2), 331–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-9993(02)00057-3

Hermann, C., & Flecker, J. (2012). Die Luft wird dünner. Das österreichische Modell in der Finanz- und Wirtschaftskrise. In S. Lehndorff (Ed.), Ein Triumph gescheiterter Ideen (pp. 134–148). VSA.

Hertel, J., Schütz, A., DePaulo, B. M., Morris, W. L., & Stucke, T. S. (2007). She’s single, so what? Journal of Family Research, 19(2), 139–158.

Hettlage, R. (2000). Individualization, pluralization, post-familiarization: dramatic or dramatized upheavals in the modernization process in the family? Journal of Family Research, 12(1), 72–97.

Hogan, M., Leyden, K., Conway, R., Goldberg, A., Walsh, D., & McKenna-Plumley, P. (2016). Happiness and health across the lifespan in five major cities: The impact of place and government performance. Social Science & Medicine, 162, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.030

Hradil, S. (2003). Vom Leitbild zum “Leidbild”: Singles, ihre veränderte Wahrnehmung und der “Wandel des Wertewandels" Journal of Family Research, 15(1), 38–54.

Inglehart, R. (2002). Gender, aging, and subjective well-being. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43(3–5), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/002071520204300309

Jamieson, R., & Simpson, R. (2013). Living alone: Globalization, identity and belonging. Palgrave Mcmillan.

Karlson, K., Holm, A., & Breen, R. (2012). Comparing regression coefficients between same-sample nested models using logit and probit: A new method. Sociological Methodology, 42(1), 286–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081175012444861

Kazepov, Y., & Verwiebe, R. (Eds.). (2021). Vienna: Still a just city? Routledge.

Kislev, E. (2019). Happy singlehood: The rising acceptance and celebration of solo living. University of California Press.

Kislev, E. (2020). How do relationship desire and sociability relate to each other among singles? Journal of Social Personal Relationships, 37(8–9), 2634–2650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520933000

Kislev, E. (2021). Reduced relationship desire is associated with better life satisfaction for singles in Germany: An analysis of pairfam data. Journal of Social Personal Relationships, 38(7), 2073–2083. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211005024

Klein, J. (2022). Single shaming: Why people jump to judge the un-partnered. BBC.

Klinenberg, E. (2012). Going Solo. The extraordinary rise and surprising appeal of living alone. The Penguin Press.

Koropeckyj-Cox, T. (2005). Singles, society, and science: sociological perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 16(2/3), 91–97.

Koropeckyj-Cox, T., Romano, V., & Moras, A. (2007). Through the lenses of gender, race, and class: students’ perceptions of childless/childfree individuals and couples. Sex Roles, 56, 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9172-2

Kuehner, C. (2017). Why is depression more common among women than among men? The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(2), 146–158.

Leopold, T. (2018). Gender differences in the consequences of divorce: a study of multiple outcomes. Demography, 55(3), 769–797.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–251.

Leung, L., & Lee, P. (2005). Multiple determinants of life quality: The roles of internet activities, use of new media, social support, and leisure activities. Telematics and Informatics, 22, 161–180.

Levine, M. E., & Crimmins, E. M. (2018). Is 60 the new 50? Examining changes in biological age over the past two decades. Demography, 55(2), 387–402.

Litschauer, K., & Friesenecker, M. (2021). Affordable housing for all? In Y. Kazepov & R. Verwiebe (Eds.), Vienna Sill a Just City? (pp. 68–82). Routledge.

Lopez Ulloa, B. F., Valerie, M., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2013). How does subjective well-being evolove with age? A literature review. Population Ageing, 6, 227–246.

Luhmann, M., & Hawkley, L. (2016). Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Developmental Psychology, 52(6), 943–959.

Magee, W. (2015). Effects of gender and age on pride of work, and job satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 1091–1115.

Matsuura, T., & Ma, X. (2021). Living arrangments and subjective well-being of elderly in China and Japan. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00430-0

McCabe, M., Cummins, R., & Romeo, Y. (1996). Relationship status, relationship quality, and health. Journal of Family Studies, 2(2), 109–120.

Meisenberg, G., & Woodley, M. (2015). Gender differences in subjective well-being and their relationship with gender equality. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(6), 1539–1555.

Millward, P. (2003). The ‘grey digital divide’: perception, exclusion and barriers of access to the internet for older people. First Monday, 8(7). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v5218i5217.1066

Mood, C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82.

Oh, J., Chopik, W., & Lucas, R. (2021). Happiness singles out: bidirectional associations between singlehood and life satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bullentin, online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211049049

Overall, N., Fletcher, G., & Simpson, J. (2010). Helping each other grow: Romantic partner support, self-improvement, and relationship quality. Personality and Social Psychology Bullentin, 36(11), 1496–1513.

Park, Y., Impett, E., & MacDonald, G. (2021). Singles’ sexual satisfaction is associated with more satisfaction with singlehood and less interest in marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bullentin, 47(5), 741–752.

Park, Y., MacDonald, G., Impett, E., & Neel, R. (2023). What social lives do single people want? A person-centered approach to identifying profiles of social motives among singles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, online first. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000455

Piekut, M. (2020). Living standards in one-person households of the elderly population. Sustainability, 12(3), 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030992

Präg, P., Fritsch, N.-S., & Richards, L. (2022). Intragenerational social mobility and well-being in Great Britain: a biomarker approach. Social Forces, 101(2), 665–693.

Reinprecht, C. (2017). Kommunale Strategien für bezahlbaren Wohnraum: Das Wiener Modell oder die Entzauberung einer Legende. In B. Schönig, J. Kadi, & S. Schipper (Eds.), Wohnraum für alle? Bielefeld: transcript.

Riederer, B., & Berghammer, C. (2020). The part-time revolution: Changes in the parenthood effect on women’s employment in Austria across the birth cohorts from 1940 to 1979. European Sociological Review, 36(2), 284–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz058

Riederer, B., Verwiebe, R., & Seewann, L. (2019). On changing social stratification in Vienna: Why are migrants declining from the middle of society? Population, Space and Place, 25(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2215

Riederer, B., Fritsch, N.-S., & Seewann, L. (2021a). Singles in the city: Happily ever after? Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 19(1), 1–35.

Riederer, B., Verwiebe, R., & Ahn, B. (2021b). Professionalisation, polarisation or both? Economic restructuring and new divisions of labour. In Y. Kazepov & R. Verwiebe (Eds.), Vienna: Still a Just City? (pp. 99–114). Routledge.

Roblek, V. (2019). The smart city of Vienna. In L. Anthopoulos (Ed.), Smart City Emergence (pp. 105–127). Elsevier.

Ross, C. E., Mirowsky, J., & Goldsteen, K. (1990). The impact of the family on Health: The decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 52(4), 1059–1078.

Sanderson, W., & Scherbov, S. (2015). Faster increases in human life expectancy could lead to slower population aging. PLoS One, 10(4), e0121922. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121922

Sandström, G., & Karlsson, L. (2019). The educational gradient of living alone: A comparison among the working-age population in Europe. Demographic Research, 40(55), 1645–1670.

Shapiro, A., & Keyes, C. L. (2008). Marital status and social well-being: are the married always better off? Social Indicators Research, 88(2), 329–346.

Simpson, R. (2016). Singleness and self-identity: The significance of partnership status in the narratives of never-married. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(3), 385–400.

Slonim, G., Gur-Yaish, N., & Katz, R. (2015). By choice or by circumstance?: Stereotypes of and feelings about single people. Studia Psychologica, 57(1), 35–48.

Snell, K. D. M. (2017). The rise of living alone and loneliness in history. Social History, 42(1), 2–28.

Stack, S., & Eshleman, R. (1998). Marital status and happiness: A 17-nation study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(2), 527–536.

Stahnke, B., & Cooley, M. (2020). A systematic review of the association between partnership and life satisfaction. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 29(2), 182–189.

Statistics Austria. (2021a). Bevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit und Geburtsland. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3yaRB1Y

Statistics Austria. (2021b). Ehescheidungen und Gesamtscheidungsrate seit 1995 nach Bundesländern. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3nZnlDN

Statistics Austria. (2021c). Mindestsicherungs- und Sozialhilfestatistik. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3H2vL4H

Statistics Austria. (2021d). STATCube - Statistical Database by Statistics Austria. Retrieved from https://www.statistik.at/web_de/services/statcube/. Retrieved Accessed 17 Sept 2021, from Statistics Austria https://www.statistik.at/web_de/services/statcube/

Stein, P. (1976). Single. Prentice Hall.

Ta, V., Gesselman, A., Perry, B., Fisher, H., & Garcia, J. (2017). Stress of singlehood: Marital status, domain-specific stress, and anxiety in a national U.S. sample. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 36(6), 461–485.

Teitzer, R., Fritsch, N.-S., & Verwiebe, R. (2014). Arbeitsmarktflexibilisierung und Niedriglohnbeschäftigung: Deutschland und Österreich im Vergleich. WSI-Mitteilungen, 67(4), 257–266.

Troger, T., & Gielge, J. (2016). Lebensqualität in 91 Wiener Bezirksteilen. Bezirksprofile der Zufriedenheit mit der Wohnumgebung (Vol. 157). Werkstattbericht.

Van de Kaa, D. J. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin, 42(1), 1–59.

Vanassche, S., Swicegood, G., & Matthijs, K. (2013). Marriage and children as a key to happiness? Cross-national differences in the effects of marital status and children on well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 501–524.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(1), 1–39.

Verwiebe, R., & Fritsch, N.-S. (2011). Working Poor in Österreich. Verliert das Normalarbeitsverhältnis seinen armutsvermeidenden Charakter? In R. Verwiebe (Ed.), Armut in Österreich (pp. 149–167). Braumüller Verlag.

Verwiebe, R., Troger, T., Wiesböck, L., Teitzer, R., & Fritsch, N.-S. (2013). GINI country report: growing inequalities and their impacts in Austria. AIAS Amsterdam Insitute for Advanced Labour Studies.

Verwiebe, R., Fritsch, N.-S., & Liedl, B. (2019). Der Arbeitsmarkt in Österreich: Auswirkungen des Strukturwandels für Einheimische im Vergleich mit Migrantinnen und Migranten. In W. Aschauer, M. Beham-Rabanser, O. Bodi-Fernandez, M. Haller, & J. Muckenhuber (Eds.), Die Lebenssituation von Migrantinnen und Migranten in Österreich (pp. 113–153). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Verwiebe, R., Haindorfer, R., Dorner, J., Liedl, B., & Riederer, B. (2020). Quality of Life in a Growing City: Executive Summary. City of Vienna, Municipal Department MA 18 – Urban Development and Planning. https://www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/studien/pdf/b008584.pdf

Waite, L. J. (1995). Does marriage matter? Demography, 32(4), 483–507. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061670

Walker, A. (2005). A european perspective on quality of life in old age. European Journal of Ageing, 2(1), 2–12.

Wilkinson, K., & Rouse, J. (2022). Solo-living and childless professional women: Navigating the ‘balanced mother ideal’ over the fertile years. Gender, Work & Organization, 30(1), 68–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12900

Wohnservice Wien. (2019). Älter werden - individuell wohnen! Wohnservice Wien.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

This manuscript has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 64.2 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fritsch, NS., Riederer, B. & Seewann, L. Living Alone in the City: Differentials in Subjective Well-Being Among Single Households 1995–2018. Applied Research Quality Life 18, 2065–2087 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10177-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10177-w