Abstract

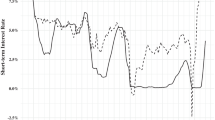

This paper focuses on the European Union (EU) and European Monetary Union (EMU) as club-governments after an analysis of the characteristics of the union of governments as clubs. Convergence among member countries regarding the parameters relevant for club homogeneity and stability is paramount. We develop empirical research on the convergence path in a model with the five main EU countries, with 15 parameters drawn from neoclassical growth theory and from EU-EMU rules. We examine convergence and stability in the EU club for France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom by measuring their parametric spreads from 2003 (first year of normal circulation of the euro) to 2011. Convergence with growth developed before the great financial fluctuation, then divergence set in. Convergence then reappeared with partial stagnation. Gross domestic product (GDP) was the dominant parameter, while GDP per capita was the least important. The main focus of the paper is on measurement. The results signal the need for changes in institutions and policy tools consistent with the market economy models of the two clubs. Further integration will face the same issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

One should not confuse monetary union with the currency association of a state to the currency of another state. Argentina pegged its pesos to the US dollar. The pegging did not work and Argentina was obliged to leave the legal parity with the dollar. Lichtenstein pegged its currency to the Swiss Franc with better results. The Kingdom of Monaco, the Republic of San Marino and the Vatican State use the euro as their currency by a bilateral pact with the EMU (i.e. the European Central Bank (ECB)). If they leave the euro breaking the pact, they must either issue their own currency or, more easily, adopt another currency, with a bilateral pact. The two examples of past monetary unions, the Latin Monetary Union and the Scandinavian Monetary Unions, both of the 19th century, do not correspond to the territorial club model of the EMU, as there was no central bank.

The evolution of the five club members considered here has already been tentatively studied using 29 parameters taken almost at random among those available in the three years 2000, 2005, and 2010 (Caputo 2014a). The results were inconclusive, mostly due to the limited resolution of the data and to the limited time interval used.

The simple method used here has some similarity with the Hamming method (Hamming 1950). It allows results of different type, such as the quantified definition of the inhomogeneity of the clubs and of their internal and comparative spreads, very useful from the point of view of economy and finance. The Hamming method would need manipulations to give the required results perhaps of inadequate quality for the limited number of entities used. The pattern recognition method, already successfully used for the study of the evolutions of banks (Caputo et al. 1997), would basically need the analysis of two club members and, with some manipulation of the procedure, it could give appreciable results (Caputo 2014a).

Notice that this worrying phenomenon in the results clears when the inhomogeneity and instability trends and the rate of growth in GDP for the five countries, with regard to the sum of the 15 parameters, are normalized to the same scale. Without this normalization, the phenomenon would remain concealed.

At first, it is less clear why distances and spreads in the value added of agriculture on GDP should matter. However, this spread is clearly a proxy for the different social structure of the northern and southern countries, with Germany and the UK on one side, Spain and Italy on the other, and France in between but more close to the southern countries as one can see from Table 8.

Table 8 Value added of agriculture/GDP in five EU major countries, 2003–2013

References

Barro, R. J., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1992). Convergence. Journal of Political Economy, 2, 223–251.

Barro, R. J., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1994). Economic Growth (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Baumol, W. J. (1986). Productivity Growth, Convergence, and Welfare: What the Long-run Data Show. American Economic Review, 76(5), 1072–1085.

Ben-David, D. (1997). Convergence clubs and subsistence economies. Cambridge, Mass: NBER Working Paper no. 6267.

Berglas, E. (1976). On the Theory of Clubs. American Economic Review, 66(2), 116–121.

Buchanan, J. M. (1965). An Economic Theory of Clubs, Economica reprinted in Buchanan (2001a).

Buchanan, J. M. (1990). Europe’s Constitutional Opportunity, Institute of Economic Affairs of London , reprinted in J. M. Buchanan, (2001b).

Buchanan, J. M. (1995). Federalism as an Ideal Political Order and an Objective of Constitutional Reform, in Publius: the Journal of Federalism, reprinted in Buchanan, J. M. (2001b).

Buchanan, J. M. (1996). Federalism and Individual Sovereignty, in Cato Journal, reprinted in Buchanan J. M. (2001b).

Buchanan, J. M. (1997). National Politics and Competitive Federalism: Italy and the Constitution of Europe, in Buchanan J. M. (1997), reprinted in Buchanan J. M., (2001b).

Buchanan, J. M. (2001a). Externalities and Public Expenditure Theory Vol. 15 of the Collected works of J. Buchanan, edited by Jeffrey Brennan, Liberty, Fund, Indianapolis.

Buchanan, J. M. (2001b). Federalism, Liberty and the Law, Vol 18 of the Collected works of J. Buchanan, edited by Hartmut Kliemt, Liberty, Fund, Indianapolis.

Buchanan, J. M., & Goetz, C. J. (1972). Efficiency limits of fiscal mobility: An assessment of the Tiebout model. Journal of Public Economics, 1(1), 25–43.

Busetti, F., Forni, L., Harvey, A., & Venditti, F. (2007). Inflation Convergence and Divergence within the European Monetary Union. International Journal of Central Banking, 3(2), 95–121.

Caputo, M. (2012a). The convergence of economic developments. Non Linear Dynamics and Econometrics, 16, 2–22.

Caputo, M. (2012b). The Importance of Dynamic phenomena with memory. The effect of the convergence of economic and cultural development, in, Recent Advances in Continuous -time Econometrics and Economic Dynamics. Contributions in Honor of Giancarlo Gandolfo, in Studies in Non Linear Dynamics and Econometrics, vol. 16 n.2.

Caputo, M. (2014). The evolution and the homogeneity of EU economies (with an econometric approach), Conference on New Trends in Fluid and Solid Mechanics, Vietri, April, 2013, DOI 10 1007/s11012-014-9966-1, Meccanica.

Caputo, M. Kolari, J. (1997). Pattern recognition of the financial condition of Banks II, Giornale dell’Istituto Italiano degli Attuari, 61–80.

Cavenaille, L. & Dubois, D. (2010). An Empirical Analysis of Income Convergence in the European Union, CREPP WP No. 2010/01.

Cornes, J., & Sandler, T. (1996). The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods and Club Good (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cunado, J., Gil-Alana, L. A., & Pérez de Gracia, F. (2006). Additional Empirical Evidence on Real Convergence: A Fractionally Integrated Approach. Review of World Economics, 142, 67–91.

Dowrick, S. & DeLong, A.J.B. (2003). “Globalization and Convergence” in Bordo M.D., A. M. Taylor and J. G. Williamson, ( editors), (2003), Globalization in historical perspective (pp. 191–220). NBER Conference Report series, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Dowrick, S., & Nguyen, D. T. (1989). OECD comparative economic growth 1950–85: Catch-up and convergence. American Economic Review, 79(5), 1010–1030.

Fedeli, S., & Forte, F. (2012). Public Debt and Unemployment Growth. The need for Fiscal and Monetary Rules. Evidence from the OECD Countries. Economia Politica, 3, 409–438.

Fischer, M., & Stirbock, C. (2006). Pan-European regional income growth and club-convergence. The Annals of Regional Science, 40(4), 693–721.

Galor, O. (1996). Convergence? inferences from theoretical models. The Economic Journal, 106(437), 1056–1069.

Hamming, R. W. (1950). Error Detecting and Error Correcting Codes. The Bell System Technical Journal XXIX, 2, 147–160.

Islam, N. (2003). What have we learnt from the convergence debate? Journal of Economic Surveys, 17(3), 309–362.

Mathunjwa, J.S. & Temple, J.R.W. (2007). Convergence Behavior in exogenous growth models, Department of Economics, University of Bristol.

Mundell, R. A. (1961). A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas. American Economic Review, 51(4), 657–665.

Mundell, R.A. (1973). A Plan for a European Currency, in H.G. Johnson and A.K.Swoboda, (1973), The Economics of Common Currencies, Allen and Unwin: pp. 143–72.

Pauly, M. (1970a). Optimality, Public Goods and Local Government: A general theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 78, 572–585.

Pauly, M. (1970b). Cores and Clubs. Public Choice, 9, 53–65.

Reiss, J.P. (2000). On the convergence speed in growth models, FEMM Working Paper No. 22.

Sandler, T., & Tschirhart, J. (1980). The Economic Theory of Clubs: An Evaluative Survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 18(4), 1481–1521.

Sandler, A., & Tschirhart, T. J. (1997). Club Theory: Thirty Years Later. Public Choice, 93(3–4), 335–355.

Scotchmer, S. (2002). “Local Public Goods and Clubs” in Auerbach A.and M.Feldstein, (editors), Handbook of Public Economics, Volume 4, Elsevier Science.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Elena Costarelli for assistance in the editing of this paper. The usual disclaimer applies, meaning that all remaining errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caputo, M., Forte, F. Difficult Convergence among the Five Main European Union Countries and the Crisis of the Euro Area. Atl Econ J 43, 415–430 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-015-9480-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-015-9480-4