Abstract

The media has a major influence on public opinions and legitimacy for NGOs, which can have a serious impact on the effectiveness of NGOs’ programs. However, media biases often affect the framing of media objects. For instance, western countries are often portrayed negatively by the media of the Muslims countries. This anti-western bias is less prevalent in English-language media when compared to the local languages newspapers as the English-language media generally target the elites who often hold less anti-western opinions than the general population. As NGOs are usually considered a western construct in the Muslim world, I test whether the media’s sensitivity to its consumers’ sentiments extends to the coverage of NGOs by comparing English and local language (Urdu) newspapers in Pakistan. I confirm that Urdu newspapers portray NGOs more negatively than English-language newspapers and are more likely to question NGOs’ effectiveness and accountability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Muslim world faces today issues resulting from abject poverty (Rahman 2013; Rubin 2014; Kuran 1997) which, in addition to a human catastrophe, also attracts some individuals to radical and extremist ideologies (Nasr 2000; Berman 2009; Bano 2012a). NGOs can help alleviate these social problems, but they often suffer from a lack of legitimacy in the Muslims world (Khan et al. 2010; White 1999). The media can help improve public perceptions of NGOs as it helps to mold public opinions. Therefore, attaining public legitimacy through the media can enhance an NGO’s impact and legitimacy in its beneficiary communities (Borchgrevink 2017; Popplewell 2018; Schlesinger et al. 2004). Previous research suggests that the media generally portrays NGOs in a positive light (Deacon et al. 1995; Martens 1996; Marberg et al. 2016; De Souza 2010; Jacobs and Glass 2002; Deacon et al. 1995; Greenberg and Walters 2004). Yet the media often has its own biases, and these biases affect its framing of media actors. For instance, in the Muslim world, the media portrays western countries negatively because of the media’s anti-western bias (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2003, 2010). In the global South, NGOs are often considered a western construct because of their close association with western donor aid (Bano 2012b). This poses an important question: Does the media’s anti-western bias in Muslims countries affect their portrayal of NGOs because of their association with aid from western countries?

To answer this question, this paper analyzes the newspaper media in Pakistan. Pakistan is a Muslim-majority country where western countries like the USA have low public approval ratings for several reasons, including a history of colonialism, their support of Israel, and, more recently, the War on Terror.Footnote 1 The media is sensitive to its consumers’ anti-western sentiments, and they often portray the USA as the central villain in its coverage. While arguably some western countries like France and Germany have opposed some US policies in the Muslim world, western countries are often referred to as the “western civilization” as a whole, similar to how Muslim nations are labeled as part of the “Islamic civilization” by the western media (Huntington 2007). Consequently, western countries are often framed negatively in the Pakistani press (Tavernise 2010; Pintak and Nazir 2013; Hassan 2014).

However, in general, the language gap defines newspaper readership in Pakistan. The media frames its news to closely resemble its readers’ views (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2010, 2003, 2006). English, Pakistan’s official language, caters to the generally more liberal and anti-western elites Rahman 2002). In contrast, local language newspapers focus on the generally more conservative and anti-western non-elites. Consequently, the local language media frames are more anti-western in sentiment than English-language newspapers (Hassan 2014; Ricchiardi 2012).

NGOs emerged in the 1980s in Pakistan with financial support from western donors (Brinkerhoff 2003; Salim et al. 2012; Bano 2018; Borchgrevink 2017). This funding structure creates the possibility that the international clientele and the local clients’ expectations do not cohere. Consequently, citizens are often unaware of the “principals” NGOs serve, and some leaders exploit this confusion to portray NGOs as pawns of foreign agents (Lee et al. 2012).

Local citizens often consider NGOs as “western” constructs, and the word “NGO” has become synonymous with organizations that are dependent on foreign donor funding (Bano 2008), and as such traditional nonprofit organizations prefer the label of an NGO. The distinction between NGOs and western governments becomes further blurred because, in addition to humanitarianism, western countries have advanced their military interests through NGOs (O’Dempsey et al. 2009). For instance, NGO humanitarian camps were used by western governments to train Afghans fighters against the Soviet Union during the Afghan War. Similarly, the CIA used Save the Children campaign to collect information on Bin Laden, leading to the expulsion of 29 NGOs for allegedly helping collect intelligence for western governments (Mullaney and Hassan 2015; Rodriguez 2011).

I hypothesize that the media’s sensitivity to their readers’ preferences affects their portrayal of NGOs because of their association with western countries. To test my hypothesis, I conduct a media frame analysis of English and Urdu language newspapers in Pakistan. Urdu is Pakistan’s national language, and it is widely understood irrespective of a Pakistani’s ethnic background (Qadir and Alasuutari 2013). I find that Urdu language newspapers are more likely to portray NGOs negatively than English-language newspapers in Pakistan. Moreover, Urdu language newspapers are more likely to question the effectiveness and accountability of NGOs and are less likely to cover the good work that NGOs are accomplishing in Pakistan. Similarly, I find support that the Urdu media is more likely to report on the government’s attempts to restrict NGOs’ activities.

These findings suggest that the media’s anti-western opinions influence its portrayal of NGOs, particularly in the local language newspapers, which are often the only media accessible to NGOs’ target population. Their support is crucial for the success of NGOs’ works in local communities. Therefore, to improve their representation in the local newspapers, the NGOs may have to distance themselves from association with western countries and work more proactively with local language journalists to address their misapprehensions about their activities.

NGOs’ Legitimacy, Foreign Funding, and Media

Western countries currently channel a large proportion of foreign aid (more than 13% of OECD countries’ assistance in 2012) through NGOs (Aldashev and Navarra 2018). Consequently, over time, the term “NGO” has become associated with organizations funded by western governments. As an illustration, a survey in Pakistan discovered that most western-donor-funded organizations refer to themselves as NGOs and that anyone familiar with the term NGO immediately associates it with donor aid (Bano 2008). Other scholars also suggest that the public generally associates the word “NGO” with western-donor-funded organizations (Lewis 2001; Anheier and Salamon 1998; Khan et al. 2010).Footnote 2

Thus, funding sources mainly distinguish NGOs from a locally funded organization (e.g., Edhi Foundation) as most an NGO’s funding comes from donors abroad. In general, there are two categories of NGOs in Pakistan: international NGOs (INGOs) that are owned and managed from foreign countries like the Save the Children, or local NGOs which generally refer to locally owned and operated organizations that are funded by donors abroad like Sungi Foundation (Evans 2014).

As per estimates, Pakistan has more than 45,000 active and operational NGOs. Among them, a tiny percentage (around 75) are international NGOs (Ministry of Interior 2020). Some international NGOs have religious motivations (for instance, Christian Development Organizations and World Vision), while the vast majority are secular western organizations (more than 95%) like Oxfam and UN agencies.

Most local NGOs receive funding from several international as well as religious and secular donors, making it impossible to distinguish between NGOs based on their donors’ religious and national affiliation. As an illustration, Idara-e-Taleem-o-Agaahi, a local NGO with 25 offices across Pakistan, is funded by several donors from the USA, Canada, UK, and the European Union, various UN agencies, as well as religious donors like World Vision.

Western donor funding affects NGOs’ legitimacy as it signals to the citizens that the NGOs prioritize the donors’ preferences over their needs because of their financial dependence on donors (Khan et al. 2010; Ahmad 2000). NGOs rely heavily on legitimacy as they do not have any coercive power, and therefore usually employ legitimacy for soliciting voluntary cooperation from various stakeholders (Schlesinger et al. 2004; Thaut et al. 2012; Fowler 1991). A legitimacy deficit thus severely impacts an NGO’s ability to garner funds, influence policy, and build trust within beneficiary communities (Schlesinger et al. 2004; Thaut et al. 2012; Fowler 1991).

The media creates legitimacy for NGOs. Consequently, most large NGOs today have a dedicated public relations department to manage their image and pick up issues that garner the media’s attention (Ron et al. 2005; Sobieraj 2011; Martens 1996). However, the media is very selective about covering NGO news. It primarily covers activities of large and service-oriented NGOs and favors covering non-contentious NGO activities (Deacon et al. 1995; Jacobs and Glass 2002; Greenberg and Walters 2004).

Previous research suggests that the media generally portrays NGOs positively (Marberg et al. 2016). However, research to date has focused on the media in the global North or on elite English newspapers in the global South (De Souza 2010). Yet, most people in the global South do not know the English language, as discussed above. Similarly, research has not looked at media biases for NGOs (Fan et al. 2013). Scholarly evidence suggests that the media is biased as newspapers are sensitive to their readers’ opinions and align their frames with these views (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2010, 2006; Mullainathan and Shleifer 2005; Lord et al. 1979).

In Muslim countries like Pakistan, the media often employs anti-western frames to adhere to its viewers’ beliefs (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2003). For instance, while the European Union is viewed more favorably than the USA (35% vs 12%), the approval rating of both the EU and the USA is considered low (below 50%) in Pakistan (Braghiroli and Salini 2014). We can trace this anti-western sentiment to the anti-colonial struggle against the British (Gilmartin 1991). Other notable reasons for the anti-western feelings include western (mainly American) involvement in Pakistan’s internal political and economic affairs, their support of Israel in the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict, western countries’ refusal to support Pakistan against India, their opposition to Pakistan’s nuclear program, as well as their refusal to support Pakistan after the Afghan War against the Soviet Union (Kizilbash 1988; Blaydes and Linzer 2012). In some instances, this anti-western sentiment has also turned into violence. For example, in 1979, an angry mob stormed the US embassy in Islamabad (Ullah 2013).

The War on Terror has accentuated these anti-western sentiments. In particular, drone strikes have generated considerable public suspicion and hostility toward western countries (Yusuf 2011; Tavernise 2010; Hassan 2014). This anti-western sentiment is not unique to Pakistan as a large proportion of the Muslim world views globalization and the spreading influence of western culture as potential threats to local beliefs (Esposito and Mogahed 2008; Demant 2006; Fisher 2012).

In line with the general public sentiment, the Pakistani newspapers are very critical of the West and the War on Terror. The New York Times described Pakistan’s newspaper industry as “rambunctious… [weaving] a black-and-white narrative in which the West is the central villain” (Tavernise 2010).Footnote 3 These dramatized anti-western frames leverage better news ratings while also augmenting the readerships’ anti-western sentiment (Hassan 2014; Pintak and Nazir 2013; Ricchiardi 2012; Yusuf 2011).

While NGOs should maintain their neutrality in political conflicts (O’Dempsey et al. 2009), several events have blurred the line between the humanitarian NGO activities and military activities of the western countries. For instance, the CIA used Afghan refugee camps to train the Afghan Mujahideen in their fight against Soviet Unions (Baitenmann 1990). More recently, the US government used Save the Children vaccination program for gathering intelligence on Bin Laden in Pakistan (Mullaney and Hassan 2015).Footnote 4

The military use of NGOs blurs the line between NGOs and western governments’ security interests and augments perceptions that all western NGOs are extensions of the western countries’ foreign policy. Consequently, militants often target NGOs for their perceived military links with the military, notably in Sudan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan (Shetty 2007). The western governments do not deny these associations. After 9/11, for instance, US Secretary of State Colin Powell called NGOs as “force multipliers,” and the UK Prime Minister Tony Blair called for the need for a military-humanitarian coalition (Lischer 2007).

Therefore, it is plausible the NGOs’ close connection with western donors affects their media representation. As mentioned above, scholarly evidence suggests that the media tailors its coverage with its audiences’ political views (Mullainathan and Shleifer 2005; Lord et al. 1979). However, there is a class and language divide among the media consumers in Pakistan. The elites are more likely to read English-language newspapers, while the non-elites are more likely to consume local language newspapers. Likewise, the elites are generally more liberal and hold less anti-west opinions than their non-elite counterparts.

British colonial policies kick-started this divide in the liberal-conservative opinions based on language as these policies introduced English as the official language. The British also launched an English-language education program, which taught “western” values to the local elites. Through these institutions, the British formed “a class of persons, Indian in blood and color, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect” (Macaulay 1952).

Post-independence, this language divide between the elites and non-elites in Pakistan has persisted. As a result, English is associated with the westernized elites in Pakistan who are exposed to the western media, travel abroad often, and have peers with similar experiences (Rahman 2002). Hence, their opinions are more likely to be less anti-western. On the other hand, local language education system products do not gain similar experiences; therefore, they hold higher anti-western views. As an illustration, a survey of Pakistani schools demonstrated that English-language students are more likely to favor “western” values like equal rights for minorities and women than students in local-language schools (Rahman 2002). These views are not unique to Pakistan. Research across the global South illustrates that the elites are generally more westernized and hold less anti-west opinions than the general population (Haidar 2017; Hasan 2002; Hinnebusch 1982; Mysbergh 1957; Rubin 1992).

The media also reflects this difference in anti-western perceptions as English-language newspapers are generally less anti-western than local language newspapers (Gregory and Valentine 2009; Michaelsen 2011; Meinardus 2016). A study by International Media Support (IMS) described Pakistan’s newspaper industry as “one in which language also defines coverage.” The IMS report found that local newspapers were more popular and most influential among the general public, particularly in rural areas. The coverage was more “conservative and anti-western.” On the other hand, English-language newspapers tended to have more influence on opinion-makers, politicians, and business owners and is more “urban and elitist” (International Media Support 2009).

I hypothesize that NGOs’ association with western donor aid will influence the media representation of NGOs as the word “NGO” has become synonymous with western donor-funded organizations. There are already some suggestions that association with western countries affects the media’s evaluation of individuals and organizations because of their linkages with the West as the conservative Pakistani media often vilifies the Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai because of her perceived association with western countries (Kugelman 2017). Local language newspapers are, therefore, more likely to portray NGOs negatively because of their association with western donor aid.

To assess whether the media portrayal of NGOs is different across the local and English-language newspapers in Pakistan, I conduct an analysis of the frames that the media uses to describe them. I use Urdu language newspaper sources as a representative of local languages. Urdu is Pakistan’s national language, and it is spoken and understood widely irrespective of Pakistani ethnicity. Most importantly, most of the media in Pakistan is in the Urdu language (Rahman 2002).

Media Frames

Media frames affect public evaluations of organizations and individuals. I define framing as the selection of some aspects of a perceived reality and making them more salient in a communicating text. Frames, therefore, “highlight some bits of information,” thus “elevating them in salience” (Entman 1993). For instance, in media stories about crime, studies show that African-Americans and Latinos are more likely to be portrayed as perpetrators of crimes than as victims or police officers, which, in turn, influences perceptions of race in the USA (Bjornstrom et al. 2010). Therefore, public opinions of organizations are affected by their representation in the media (Gabrielatos and Baker 2008; Gitlin 1980; Campbell 1995).

Framing has proven to be a useful tool in previous studies on nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations (Deacon et al. 1995; Hale 2007). These frames could either be neutral, positive, or negative, which likewise influence public opinions about the NGOs. It is, therefore, imperative for NGOs to ensure that not only are they mentioned frequently, but that their media representations are positive (Sobieraj 2011).

As discussed above, the Urdu newspapers’ media framing of western countries is more negative than English-language newspapers. Therefore, I hypothesize that Urdu media’s framing of NGOs is more likely to be more negative than English-language newspapers.

H1

NGOs are more likely to obtain/acquire negative frames in Urdu newspapers than English newspapers.

Frames can either be negative or positive, but what frame topics do newspapers use to discuss NGOs? Following De Souza (2010) and Marberg et al. (2016), I analyze the main topics that newspapers employ to describe NGOs’ activities. While an article may discuss NGOs in multiple frame topics in the same article, in this article I will only be looking at the mainframe of each newspaper article. This method of analysis focuses on extracting and determining the primary theme of each article, which will help to engineer a more organized system of article classification. This method has been used in previous research, allowing scholars to classify articles systematically. As the system of assigning articles to the most suitable frame is critical to this paper, it is useful to define and explore the frames in more detail. I use frames that have been employed in previous research (Marberg et al. 2016; De Souza 2010).

Table 1 provides the details of the various frames.

When there is more than one main article frame, I look at the most important frame in the newspaper article and code it accordingly (more discussion about it in the section below).

These topics may affect how media readers perceive NGOs. For instance, an NGO depicted as “doing good” by helping resolve socioeconomic problems may be more likely to be regarded as an ethical organization by the reader. On the other hand, the reader is more likely to view an NGO depicted in a “public accountability” frame as an organization that faces issues of corruption and poor management.

If the media perceives that NGOs are not doing good work in Pakistan, we would expect that they would be less likely to portray their work as “Doing Good.” Therefore, I hypothesize that NGOs are less likely to be represented in the “Doing Good” frame in Urdu than in English-language newspapers.

H2

NGOs are less likely to obtain/acquire “Doing Good” frames in Urdu newspapers than English-language newspapers.

If the media perceives that western funding makes NGOs more responsive to western donors as opposed to local concerns, we will expect more articles to highlight the public accountability aspect of NGOs in Urdu language media.

H3

NGOs are more likely to obtain/acquire “Public Accountability” frames in Urdu newspapers than English-language newspapers.

Moreover, if the media is suspicious of NGOs’ activities in Pakistan, they are more likely to portray NGOs in the “government resistance” frame where the government is taking steps to curtail NGOs’ activities in Pakistan.

H4

NGOs are more likely to obtain/acquire “Government Resistance” frames in Urdu newspapers than English-language newspapers.

Similarly, if the Urdu media is more likely to be suspicious of NGOs’ activities, they may be less likely to portray them as organizations that speak out against government or business activities that are unethical, harmful, irresponsible, illegal, or threatening.

H5

NGOs are less likely to obtain/acquire “Protest” frames in Urdu newspapers than English-language newspapers.

Data and Analysis

I collected 656 newspaper articles from the newspaper archives at the Press Information Department (PID) at the Ministry of Information in Islamabad, Pakistan. The data include 467 English-language newspaper articles and 189 articles from the Urdu language.Footnote 5

Based on the last authoritative figure available from 2008, the archive contains the most widely circulated newspapers in Pakistan in both Urdu (Jang, Nawa-i-Waqt, and Khabrian), as well as English (The News, and Dawn) (Banerjee and Logan 2008). While we do not have authoritative information about the circulation of the rest of the newspapers, the rest of the sample also comes from widely circulated, and prominent national newspapers like Ausaf, Khabrain, and Express as the majority of Pakistan’s newspapers strive for national readership and simultaneously publish from several cities. (Shah 2010). However, various newspaper groups dominate the market in different parts of Pakistan which are included in the archive. As an illustration, Jang is the most circulated newspaper in Pakistan and holds a virtual monopoly of Urdu readership in all the major urban centers in Pakistan in the five provinces of Pakistan. Likewise, Dawn holds dominance over English readership in Karachi, the largest city in Pakistan. Another newspaper Nawa-i-Waqt is very influential in both the urban and rural Punjab, the largest province of Pakistan. Thus, in terms of geography, while we do not have any data to claim that the archive is covering the full diversity of the Pakistani newspaper industry, these newspapers include all the major population centers and the most circulated newspapers in Pakistan(Banerjee and Logan 2008).

Details of the number of articles from each newspaper are given in “Appendix 4”. Very often, the name of the publication was not given in the archive, or the name of the paper was not clear to read, in which case the newspaper name was categorized as “not clear.” The archive obtains newspaper articles from major newspapers in Pakistan and organizes them by topic and year. It is mostly for government use, but research scholars can access it after prior consent from the government. The archive is unique as it contains Urdu language newspapers by topics in its record as almost all online newspaper archives only contain only English-language newspapers. I look at articles from the 1993–2005 period (details of newspapers by language per year in “Appendix 1”) because of the lack of availability of the latest newspaper data after 2005. The article also misses the data from 1995 as the archive did not collect the articles for 1995. Therefore, the paper cannot assess how newspapers are currently portraying NGOs. While we do not have the latest newspaper articles, we have some reason to believe that the framing of NGOs may be similar in newspaper articles today as it was during the period under consideration. For instance, post 9/11 events and the subsequent War on Terror may have fueled anti-western sentiments in Pakistan, a period that this paper covers. Similarly, there was no major event in Pakistan in 1995 that may have sparked a change in the media framing of NGOs in the English and Urdu language newspapers.

I conduct frame analysis in two steps. First, I assess the negative portrayal of NGOs in an article by performing sentiment analysis of each article. Second, I identify the mainframe/topic of the article. As an illustration, a 1994 article from the Daily Muslim titled “Government starts probing the validity of NGOs” discusses the steps the government is taking to close fake NGOs in Pakistan. The main topic is government resistance as it talks about the restrictions government is putting in place to limit NGOs’ activities, while the sentiment of the article toward NGOs is negative as it is suggesting that some NGOs are fake, and therefore they are not serving the interests of the local population.

In the next sections, I discuss how I conducted sentiment analysis and topic/frame analysis of the articles.

Sentiment Analysis

For the first step, I assess if the frames employed by the media to describe NGOs are more negative in Urdu when compared to English newspapers by conducting sentiment analysis of newspaper articles. Sentiment Analysis is the analysis of the negativity of the media frames (Medhat et al. 2014). Corporate organizations employ similar tools to analyze reviews from customers and the media (Fan et al. 2013). For instance, scholars have used Amazon reviews to measure sentiment about Amazon products (Fang and Zhan 2015). A growing body of information sciences research analyzes if the media frames employed by newspapers about different actors are negative or positive (Balahur et al. 2013).

In my paper, I use manual coders to read articles and assess if the overall sentiment of an article is negative or not. While computational sentiment analysis is very useful for analyzing a large corpus of documents, manual coders provide better accuracy than computational sentiment analysis (Young and Soroka 2012). I employed a pair of bilingual (Urdu language and English speaking) undergraduates from Pakistan to code the articles.

Individual evaluations of articles may vary as it is often difficult to assess the overall sentiment of the article. Journalists are often less explicit about their sentiment evaluations in the article when compared to other kinds of media like customer reviews or movie reviews(Balahur et al. 2013). Thus, it is challenging to code the articles on a 1–5 scale as there are often disagreements between coders on issues whether an article is 3 on the scale versus being 4 on the scale. To deal with this issue of inter-rater reliability, I used various scales in the pre-testing phase to ensure that there is a higher degree of reliability in my measures. However, because of the difficulty of assessing sentiment in a newspaper, the coders will sometimes not agree.

Thus, to assure that my results can achieve a high level of reliability, I ended up creating a dichotomy of coding (negative or not negative). As we are primarily interested in negative sentiment, I restricted the analysis to measure the negative sentiment as opposed to positive sentiment in the article. Any article that depicts NGOs negatively was coded as a negative article, while an article with a neutral or positive tone was coded as non-negative. While this scale may reduce some nuances in the sentiment (say between slightly negative and very negative), it enables us to make our study replicable as a different individual will come at similar conclusions when reading these articles (as illustrated by the very high degree of inter-rater reliability between coders). For the tiny percentage of articles that the coders disagreed on, we held a meeting to decide the sentiment of the article. The coders usually came to a consensus about the sentiment. On the rare occasion that they did not, I used my vote as the third coder.

Overall, the inter-rater reliability score was high (0.90). The coders agreed 95% of the time if the article was depicting NGOs negatively, which is high, considering the subjective nature of the articles.

Some articles were easy to code. For instance, an article in daily Jang in June 1993 starts with the headline “European Embassies have stopped giving grants to fake NGOs.” Here both coders agreed that the NGO was being depicted negatively by the newspaper as some of them were framed as fake. Some articles, however, were more difficult to code. For instance, an article called “NGOs: A Double-Edged Sword” published in Daily News in June 1993 discussed the issues of NGO accountability in the first half of the article while praising NGOs in the second part of the article. The coders initially disagreed on the sentiment of these articles. However, to ensure more reliability, we made a rule of counting the number of lines in which negative or positive sentiment exists. If more lines exist in the article that talks about the negative aspects of NGOs’ works, then it was coded as negative. This coding has its limitations as it is often challenging to quantify articles from being extremely negative to negative. However, we had to come up with rules that allowed us to code articles systematically. We initially started without these rules and soon realized that coders would often not be able to agree on the sentiment of articles that portrayed NGOs negatively as well as positively. If the coders were still not able to reach a consensus, I used my vote as the third coder to decide the frame.

As can be seen below, a higher percentage of Urdu language newspapers (63%) portray NGOs negatively than Urdu language newspapers (37%) (Table 2).

Table 3 also gives the percentage of negative sentiment expressed by each newspaper. As can be seen, almost all English newspapers (The Muslim, The Nation, The News, Pakistan Times, Pakistan Observer and Frontier Post) express less negative sentiment toward NGOs than Urdu language newspapers (Nawa-i-Waqt, Khabrain, Jasarat, Ausaf, and Al Akhbar). The only exception for the Urdu language newspapers is Jang and Daily Express, whose negative sentiment lies between English-language newspapers.

Since our distribution is primarily composed of the number of times a “negative” sentiment exists in a newspaper (which is negative or non-negative), I run a binomial regression. The negative binomial distribution is a discrete probability distribution of the number of successes (0 or 1) in a dataset. Since we are assessing the probability of successes or failures, a normal count distribution like Poisson or a simple linear regression over a continuous population would not be an appropriate model to use.

I control for various factors that may affect the framing of NGOs. For one, the framing may be affected by whether the story was an editorial or a news story. Authors are more likely to give their opinion and take a stance in an opinion piece as compared to when it is a news story, as they often feature events where the author’s opinion might be less apparent. I also control for the year as current events happening in a year (for instance after the year 2001 may have affected the portrayal of NGOs due to their close association with the US and War on Terror). I also control for the size of the article as the size of the article may affect sentiment as more space may allow the author to clarify their sentiment than a smaller article. I use the newspaper article size as a measure of the article prominence as an article that takes more space is going to be more important than a news item that takes less space. While it would be ideal to have the page number as a measure of the prominence of a newspaper article (for instance, front page), the archive does not mention what page number of the article.

It is also possible that the sentiment may be driven toward specific types of international NGOs. For instance, the sentiment may be driven by INGOs from the US. Thus, initially, we attempted to code articles for specific mention of the country. However, the practice proved futile as most articles would contain either mention of “western” NGOs, or donors and countries from several countries. Thus, to control for that, I made a category of international NGOs to control all International NGOs so I can control sentiment that maybe being driven by an INGO’s association with a specific country like the US.

I also wanted to control for local NGOs that may be funded by specific countries as NGOs funded by the US may have particular negative sentiment attached to them. However, in the case of local NGOs, most of the time it is near impossible to associate any specific NGO with a country as local NGOs are often simultaneously funded abroad from multiple donors (US, Canada, UK, European Union) as well as several secular and religious western donors, thus making it impossible to associate these NGOs with a specific country or a specific religious cause. However, the sentiment may be driven by specific NGO activity areas rather than the NGO identity. For instance, the authors may be more supportive of NGOs working on education than NGOs working on women’s rights, which is a much more controversial topic in Pakistan. Thus, I control for various NGO activities.

Surprisingly, issues about women’s rights are not significant, possibly suggesting that the media is not critical of NGOs’ role in promoting women’s rights in Pakistan. Sentiment in editorials is more likely to be negative than news articles, which shows that authors are more likely to express negative sentiment in editorials instead of news articles which may be more likely to give facts instead of opinions. Interestingly, authors are more likely to espouse negative sentiment in small-sized articles (Less than half A4 size or half A4 size). This finding may suggest that small-sized articles may have a less balanced portrayal of NGOs as the authors may not have enough space to talk about negative as well as positive aspects of NGOs’ work. INGOs are more likely to be portrayed negatively than local NGOs, thus providing some support that their association with western countries may partially drive the negative sentiment toward NGOs (Table 4).

Frame Topic

As a second step as discussed above, I also identify the main article topic of the frame. Two coders coded the main topic of the media frame of an article without looking at the coding of the other coder. The coders were less likely to agree on the main topic frame of articles that had multiple frames as it was a challenge to find the mainframe of an article that has multiple frames. For instance, in an article from the Daily News in 1996 titled “NGOs ask Prime Minister to enact Environmental Laws”, the NGOs are participating in a protest to ask the government to improve its environmental laws as well as educating the public as an expert about the need to have environmental laws. The article could be coded in the protest, expert as well as a doing good frame. One coder would often code the article as doing good while the second coder may code it as a protest or expert, thus illustrating the difficulty of coding the article.

There were challenges involved in coding articles that may have multiple frames. In particular, there was often confusion between the “expert” frame that previous research had employed and “doing good” or “protest” frame as there was often overlap between them. After multiple meetings, we decided that to get reliable results, we need to remove the “expert” frame.

The results for inter-coder reliability are again high but lower than the sentiment analysis (Kappa = 0.81). On articles that the coders disagreed on, we decided to have a face-to-face conversation to resolve the disagreement. Very often, the coders will come to a consensus on the mainframe of the article, but in articles that they disagreed on, I will use my vote as the third coder to choose the frame that seemed more likely to fit on the article among the frames that the coders had selected. This method, while not perfect, does allow for the majority vote to decide the mainframe.

Some articles could be easily classified into one frame. For instance, a May 2005 article in Daily Nation called “NGO Networks: Question of Credibility” was easily categorized as a public accountability frame as it discussed issues of mismanagement and public accountability in NGO networks. Some other articles, however, were more difficult to code. For instance, using the example of “NGOs: A Double-Edged Sword” again, it was challenging to assess if the article would fit in the “doing good” or “public accountability” frame as the article discusses the good work that NGOs are doing as well as the issues of mismanagement and accountability in NGOs. For such articles, we again made the rule that the mainframe should be the one that is discussed longer (counting the number of lines).

Another complication that often arose was on articles on NGO protests as the coders were not sure whether the article should be coded as “protest” or “doing good.” The NGOs were often “doing good” by protesting against injustices in society. For instance, an article called “Political Parties must give 33 percent seats for women” could be coded as either protest or doing good as NGOs were demanding that the government should give 33 percent seats in the Parliament to the women. For such articles, we made the rule that only articles in which the NGOs are physically protesting like holding a rally would be considered a protest. The above article was coded as “doing good” since there was no physical protest by NGOs on the issue.

Given below (Table 5) is the percentage of each frame found in the newspapers. The public accountability frame is the most common frame employed (33% English and 45% Urdu). Doing good frame is the second most common frame (45% English and 23% in Urdu), followed by the government resistance frame (24% in Urdu and 12% in English). The protest frame is employed almost equally by English (7%) and Urdu language newspapers (5%). Very few articles (3% for both English and Urdu) did not use any of these frames, which suggests that these frames did a good job in covering the main topics around which NGOs are framed in the newspapers.

I also ran negative binomial regressions to assess if the frames in Urdu language newspapers differ significantly from those used in English-language newspapers. I control for various factors that may affect the framing of NGOs (same as those in sentiment analysis discussed above).

I find strong support that NGOs are less likely to acquire the “doing good” frame in Urdu language newspapers than English newspapers (H2, p < 0.01). Similarly, I find strong evidence to suggest that NGOs are more likely to acquire the “public accountability” frame in Urdu language newspapers than English newspapers (H3, p < 0.05). I also find support that NGOs are more likely to acquire the “government resistance” frame in Urdu language newspapers than English-language newspapers (H4, p < 0.05). I do not find evidence that NGOs are less likely to acquire a “protest” frame in Urdu language newspapers than English-language newspapers (H5).

As far as topics are concerned, newspapers are more likely to report on NGOs’ work in women’s rights in a “government resistance” framework, which may suggest that the government is more likely to clamp down on NGOs that are working in the domain of women’s rights. Likewise, NGOs are more likely to be discussed under the individual frames in editorial, which suggests that authors are more likely to express their opinions in editorials as opposed to newspaper articles (Table 6).

Discussion

Figure 1 gives the odds ratio of various frames that are employed by the Urdu language newspapers when compared to the English-language newspapers. Overall, the Urdu language newspapers are more likely to portray NGOs negatively as the odds ratio of having a negative sentiment is 2.9 times in Urdu language newspapers to an English-language newspaper. Urdu language newspapers are also less likely to portray the NGOs in a doing good framework as the odds ratio of having a doing good frame in an Urdu language newspaper is 0.3 to that of an English-language newspaper. The odds ratio of having a public accountability frame in the Urdu newspaper is 1.6 to that to English-language newspaper, and the odds ratio of having government resistance in the Urdu language newspaper is 3.7 to that of having the same frame in English-language newspaper, respectively. This finding suggests that the Urdu language newspapers are less likely to employ a doing good frame for NGOs, while they are more likely to portray NGOs negatively and employ public accountability and government resistance frame for NGOs than their counterparts in the English-language newspapers.

Conclusion

Overall, this paper suggests that Urdu language newspapers are more likely to frame NGOs negatively than English-language newspapers (Hypothesis 1: Negative Frames). They are also less likely to discuss the NGOs’ good work in Pakistan (Hypothesis 2: “doing good” framework) and are more likely to address issues of NGOs’ public accountability (hypothesis 3: public accountability frame). I also find strong support that they are also more likely to highlight the steps that the government is taking to curb or restrict NGOs’ activities (Hypothesis 4: government resistance frame) in Pakistan. This media framing may affect NGOs’ legitimacy among the non-elite actors as their opinions are more likely to be informed by the Urdu language media.

However, we should be cautious in interpreting these results. For one, public opinion is not entirely informed by media as other cues like direct exposure to NGOs’ work also influence these opinions. Similarly, the Pakistani public already holds anti-western views, and these views may affect their perceptions of NGOs even without the media making the connection.

Some events not covered by this archive (after 2005) may have also influenced media representations of NGOs. For instance, Save the Children was involved in the US military’s operation against Bin Laden in 2011. This event may have affected NGOs’ representation in the media as NGOs seemed complicit with the US military. The archive does not cover this period, which is a limitation of this article. However, we have some reason to believe that even these events would not affect the overall difference between Urdu and English-language media. For instance, if an NGO’s role in Bin Laden’s capture may have polarized the media depending on their opinion about Bin Laden, we would expect an increase in the difference of the NGO’s portrayal between English and Urdu language media as the media’s opinion of Bin Laden may be highly correlated with their opinion about the West as more anti-western papers may be more likely to be sympathetic to Bin Laden and vice versa.

With relatively low literacy rates in Pakistan overall, some segments of the population may not be able to read Urdu newspapers as well, relying on television and the radio instead. While we do not have television and radio transcripts, we may expect that the Urdu media other than newspapers will also be affected by their anti-western sentiment as they often hire Urdu newspaper journalists. Likewise, these media formats also frame issues to match their consumers’ opinions. Thus, their consumers’ anti-western sentiment may drive their portrayal of NGOs. The archive also does not contain regional newspapers. However, I do not think local newspapers will have a massive impact since the majority of the large papers are national rather than regional.

This study also adds nuance to the understanding of the relationship between the media and nonprofits. For instance, it suggests that the media is more critical of NGOs’ work than what previous research has suggested. We may also need to seriously consider the effect of media bias on its portrayal of NGOs in various domains like health, security, and education, among others. The issue of bias may also be valuable in the study of nonprofits in the global North as well, where the media is often divided along ideological lines.

This paper is also instructional for NGO workers in Muslim countries, as it illustrates that their association with western donors may be affecting their representation in the media. It might be difficult for these NGOs to separate themselves from their donors if they are heavily dependent on their funding. However, they may try to signal their separation by at least emphasizing their roots in local communities. Today, NGOs do try to indicate their difference from western donors by recognizing the need to signal their appreciation and respect for the local culture. For instance, in Muslim countries, NGOs increasingly frame issues around female education around religion by focusing on how Islam and local culture and not western norms dictate equality for both men and women. Similarly, some NGOs also include religious leaders in their activities to signal that their actions are acceptable and legitimized by religious authorities (UNFPA 2008).

In particular, NGOs involved in more suspicious activities need to signal their independence from western donors. For instance, polio campaigns in Pakistan are highly dubious because of their association with the CIA’s attempt to capture Bin Laden (Mullaney and Hassan 2015). Thus, polio campaigns may find it necessary to signal their difference from western donors by demonstrating their local roots.

Similarly, while there is limited evidence to suggest NGOs’ sensitivity to the need for engaging local language journalists, we do have some suggestions that NGOs and western donors are taking media engagement more seriously. For instance, recently, the US embassy in Pakistan has been conducting training for NGOs to help them improve their involvement with the local press.Footnote 6 This paper suggests that NGOs need to invest more time and effort in reaching out to local journalists and demonstrating their authenticity and respect for local culture.

Notes

As an illustration, only 11% of Pakistanis have a favorable opinion of the U.S., the lowest percentage among 38 countries polled by Pew Research in spring 2013 <http://www.pewglobal.org/2013/07/18/americas-global-image-remains-more-positive-than-chinas/>.

Arguably there are also some non-western donors to these NGOs as recently donors like China, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have increased their donations to NGOs in Pakistan. However, overall, the word ‘NGO’ is often associated with western donor aid.

Television media also portrays western countries negatively. As an illustration, The Los Angeles Times reported that Pakistani media ‘television talk shows to try to gobble up ratings with sensationalism and demonization of the West (Rodriguez 2011).

In fact, the backlash and suspicion about US’s involvement with NGOs were so intense that people in many Pakistan refused vaccination from NGO workers under the suspicion that they had been tempered by the US government.

The archive is the official government repository and therefore focuses more on collecting English as opposed to Urdu language newspapers as English is the official language. Hence there are more English-language articles in the archives than Urdu language articles. However, despite the fewer number of Urdu language newspaper articles, there is no systematic reason to suggest that the collection of the articles would be systematically affected by their sentiment in the article. Hence we can assume that the sample in both Urdu and English newspapers is random and that the collection of the newspapers is not being affected by the sentiment. While ideally, we will like to collect a complete newspaper archive, no other archive of Urdu newspapers exists.

For more information: https://www.grants.gov/web/grants/view-opportunity.html?oppId=283200.

References

Ahmad, M. M. (2000). Donors NGOs, the state, and their clients in Bangladesh. Dhaka: Maniruddin Ahmed and Lutfun Nahar.

Aldashev, G., & Navarra, C. (2018). Development NGOs: Basic facts. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 89(1), 125–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12188.

Anheier, H. K., & Salamon, L. M. (1998). The nonprofit sector in the developing world: A comparative analysis. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Baitenmann, H. (1990). NGOs and the Afghan war: The politicisation of humanitarian aid. Third World Quarterly, 12(1), 62–85.

Balahur, A., Steinberger, R., Kabadjov, M., Zavarella, V., van der Goot, E., Halkia, M., Pouliquen, B., & Belyaeva, J. (2013). Sentiment analysis in the news. http://arxiv.org/abs/1309.6202[Cs].

Banerjee, I., & Logan, S. (2008). Asian communication handbook 2008. Philippines: AMIC.

Bano, M. (2008). Contested claims: Public perceptions and the decision to join NGOs in Pakistan. Journal of South Asian Development, 3(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/097317410700300104.

Bano, M. (2012a). The rational believer: Choices and decisions in the Madrasas of Pakistan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bano, M. (2012b). Breakdown in Pakistan: How aid is eroding institutions for collective action. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bano, M. (2018). Partnerships and the good-governance agenda: Improving service delivery through state–NGO collaborations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9937-y.

Berman, E. (2009). Radical, religious, and violent: The new economics of terrorism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bjornstrom, Eileen E. S., Kaufman, R. L., Peterson, R. D., & Slater, M. D. (2010). Race and ethnic representations of lawbreakers and victims in crime news: A national study of television coverage. Social Problems, 57(2), 269–293. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2010.57.2.269.

Blaydes, L., & Linzer, D. (2012). Elite competition, religiosity, and anti-Americanism in the Islamic world. The American Political Science Review, 106(2), 225–243.

Borchgrevink, K. (2017). NGOization of Islamic charity: Claiming legitimacy in changing institutional contexts. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9892-7.

Braghiroli, S., & Salini, L. (2014). How do the others see us? An analysis of public opinion perceptions of the EU and USA in third countries. Transworld, 33(June), 1–19.

Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2003). Donor-funded government—NGO partnership for public service improvement: Cases from India and Pakistan. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14(1), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022997006704.

Campbell, M. C. (1995). When attention-getting advertising tactics elicit consumer inferences of manipulative intent: The importance of balancing benefits and investments. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 4(3), 225–254. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp0403_02.

de Souza, R. (2010). NGOs in India’s elite newspapers: A framing analysis. Asian Journal of Communication, 20(4), 477–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2010.496863.

Deacon, D., Fenton, N., & Walker, B. (1995). Communicating philanthropy: The media and the voluntary sector in Britain. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 6(2), 119–139.

Demant, P. R. (2006). Islam vs. Islamism: The dilemma of the Muslim world: The dilemma of the Muslim World. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

Esposito, J. L., & Mogahed, D. (2008). Who will speak for Islam? World Policy Journal, 25(3), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1162/wopj.2008.25.3.47.

Evans, D. (2014). Journal of the international relations and affairs group, Volume IV, Issue I. Morrisville: Lulu.com.

Fan, D., Geddes, D., & Flory, F. (2013). The Toyota recall crisis: Media impact on Toyota’s corporate brand reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 16(2), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2013.6.

Fang, X., & Zhan, J. (2015). Sentiment analysis using product review data. Journal of Big Data, 2(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-015-0015-2.

Fisher, M. (2012). The history of muslim anti-western protests is older than Obama or Bush, Drones or Israel. The Atlantic. September 17, 2012. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/09/the-history-of-muslim-anti-western-protests-is-older-than-obama-or-bush-drones-or-israel/262462/.

Fowler, A. (1991). The role of NGOs in changing state-society relations: Perspectives from Eastern and Southern Africa. Development Policy Review, 9(1), 53–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.1991.tb00175.x.

Gabrielatos, C., & Baker, P. (2008). Fleeing, sneaking, flooding: A corpus analysis of discursive constructions of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK Press, 1996–2005. Journal of English Linguistics, 36(1), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424207311247.

Gentzkow, M., & Shapiro, J. M. (2003). Media, education, and anti-Americanism in the Muslim world. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 479861. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=479861.

Gentzkow, M., & Shapiro, J. M. (2006). Media bias and reputation. Journal of Political Economy, 114(2), 280–316. https://doi.org/10.1086/499414.

Gentzkow, M., & Shapiro, J. M. (2010). What drives media slant? Evidence from U.S. daily newspapers. Econometrica, 78(1), 35–71. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA7195.

Gilmartin, D. (1991). Democracy, nationalism and the public: A speculation on colonial Muslim politics. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 14(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856409108723150.

Gitlin, T. (1980). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making & unmaking of the new left. University of California Press.

Golding, P., & Elliott, P. (n.d.). Making the news. Books on Demand.

Greenberg, J., & Walters, D. (2004). Promoting philanthropy? News publicity and voluntary organizations in Canada. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 15(4), 383–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-004-1238-6.

Gregory, S., & Valentine, S. (2009). Pakistan: The situation of religious minorities. WRITENET. https://www.refworld.org/docid/4b01856e2.html

Haidar, S. (2017). Access to english in Pakistan: Inculcating prestige and leadership through instruction in elite schools. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1320352.

Hale, M. (2007). Superficial friends: A content analysis of nonprofit and philanthropy coverage in nine major newspapers. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(3), 465.

Hasan, A. (2002). The roots of elite alienation. Economic and Political Weekly, 37(44/45), 4550–4553.

Hassan, K. (2014). The role of private electronic media in radicalising Pakistan. Round Table, 103(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2013.874164.

Hinnebusch, R. A. (1982). Children of the elite: Political attitudes of the westernized bourgeoisie in contemporary Egypt. Middle East Journal, 36(4), 535–561.

Huntington, S. P. (2007). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. New York City: Simon and Schuster.

International Media Support. (2009). Media in Pakistan: Between radicalisation and democratisation in an unfolding conflict: Report. København: International Media Support.

Jacobs, R. N., & Glass, D. J. (2002). Media publicity and the voluntary sector: The case of nonprofit organizations in New York City. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 13(3), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020337425782.

Khan, F. R., Westwood, R., & Boje, D. M. (2010). ‘I Feel like a Foreign Agent’: NGOs and corporate social responsibility interventions into third world child labor. Human Relations, 63(9), 1417–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709359330.

Kizilbash, H. H. (1988). Anti-Americanism in Pakistan. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 497, 58–67.

Kugelman, M. (2017). Why Pakistan hates Malala. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/08/15/why-pakistan-hates-malala/.

Kuran, T. (1997). Islam and underdevelopment: An old puzzle revisited. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lee, T., Johnson, E., & Prakash, A. (2012). Media independence and trust in NGOs: The case of postcommunist countries. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(1), 8–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764010384444.

Lewis, D. (2001). The management of non-governmental development organizations: An introduction. East Sussex: Psychology Press.

Lischer, S. K. (2007). Military intervention and the humanitarian ‘Force Multiplier’. Global Governance, 13(1), 99–118.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(11), 2098–2109. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.11.2098.

Macaulay, T. B. M. (1952). Speeches by Lord Macaulay, with his minute on indian education; Selected, World’s Classics; CDXXXIII. London: Oxford University Press.

Marberg, A., van Kranenburg, H., & Korzilius, H. (2016). NGOs in the news: The road to taken-for-grantedness. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(6), 2734–2763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9757-5.

Martens, T. A. (1996). The news value of nonprofit organizations and issues. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 7(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.4130070207.

Medhat, W., Hassan, A., & Korashy, H. (2014). Sentiment analysis algorithms and applications: A survey. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 5(4), 1093–1113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2014.04.011.

Meinardus, R. (2016). Pakistan’s shrinking liberal minority—The globalist. The Globalist, June 5, 2016. https://www.theglobalist.com/pakistan-shrinking-liberal-minority/.

Michaelsen, M. (2011). New media vs. old politicsthe internet, social media, and democratisation in Pakistan. Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Ministry of Interior Pakistan. (2020). List of approved INGOS. Islamabad: Ministry of Interior Pakistan.

Mullainathan, S., & Shleifer, A. (2005). The market for news. American Economic Review, 95(1), 1031–1053.

Mullaney, A., & Hassan, S. A. (2015). He led the CIA to bin laden—And unwittingly fueled a vaccine backlash. National Geographic News. February 27, 2015. https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/02/150227-polio-pakistan-vaccination-taliban-osama-bin-laden/.

Mysbergh, J. H. (1957). The indonesian elite. Far Eastern Survey, 26(3), 38–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/3024308.

Nasr, V. R. (2000). International politics, domestic imperatives, and identity mobilization: Sectarianism in Pakistan, 1979–1998. Comparative Politics, 32(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/422396.

O’Dempsey, T., Munslow, B., & Shannon, R. (2009). Playing with principles in an era of securitized aid: Negotiating humanitarian space in post-9/11 Afghanistan. Progress in Development Studies, 9(1), 15–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499340800900103.

Pintak, L., & Nazir, S. J. (2013). Pakistani journalism: At the crossroads of muslim identity, national priorities and journalistic culture. Media, Culture and Society, 35(5), 640–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443713483654.

Popplewell, R. (2018). Civil society, legitimacy and political space: Why some organisations are more vulnerable to restrictions than others in violent and divided contexts. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(2), 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-9949-2.

Qadir, A., & Alasuutari, P. (2013). Taming terror: Domestication of the war on terror in the Pakistan media. Asian Journal of Communication, 23(6), 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2013.764905.

Rahman, T. (2002). Language, ideology and power: Language learning among the Muslims of Pakistan and North India. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rahman, K. (2013). Targeting underdevelopment and poverty in the Muslim world role of Islamic Finance. Policy Perspectives, 10(2), 123–132.

Ricchiardi, S. (2012). Challenges for independent news media in Pakistan. Washington: Center for International Media Assistance.

Rodriguez, A. (2011). Bin laden raid gets little credence in conspiracy-minded Pakistan. Los Angeles Times, May 31, 2011. http://articles.latimes.com/2011/may/31/world/la-fg-pakistan-conspiracies-20110601.

Ron, J., Ramos, H., & Rodgers, K. (2005). Transnational information politics: NGO human rights reporting, 1986–2000. International Studies Quarterly, 49(3), 557–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2005.00377.x.

Rubin, B. R. (1992). Political elites in Afghanistan: Rentier state building, rentier state wrecking. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 24(1), 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743800001434.

Rubin, J. (2014). Islamic institutions and underdevelopment. In: M. Kabir Hassan & Mervyn K. Lewis (Eds.), Handbook on Islam and Economic Life, Chap 29, (pp. iii–iii). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://ideas.repec.org/h/elg/eechap/16009_29.html.

Salim, L., Sadruddin, S., & Zakus, D. (2012). Organizational commitment in a health NGO in Pakistan. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23(3), 584–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-011-9209-1.

Schlesinger, M., Mitchell, S., & Gray, B. (2004). Restoring public legitimacy to the nonprofit sector: A survey experiment using descriptions of nonprofit ownership. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(4), 673–710. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764004269431.

Shah, H. (2010). The inside pages: An analysis of the Pakistani Press (Vol. 148). Washington, DC: Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

Shetty, P. (2007). How important is neutrality to humanitarian aid agencies? The Lancet, 370(9585), 377–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61177-5.

Sobieraj, S. (2011). Soundbitten: The perils of media-centered political activism. New York: New York University Press.

Tavernise, S. (2010). U.S. is a top Villain in Pakistan’s conspiracy talk. The New York Times, May 25, 2010, sec. Asia Pacific. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/26/world/asia/26pstan.html.

Thaut, L., Stein, J. G., & Barnett, M. (2012). In defense of virtue: Credibility, legitimacy dilemmas, and the case of Islamic Relief. In P. A. Gourevitch, D. A. Lake, & J. G. Stein (Eds.), The credibility of transnational NGOs: When virtue is not enough. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ullah, H. K. (2013). Vying for Allah’s Vote: Understanding Islamic Parties, Political Violence, and Extremism in Pakistan. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

UNFPA. (2008). Culture matters-lessons from a legacy of engaging faith-based organizations. New York: United Nations Population Fund.

White, S. C. (1999). NGOs, civil society, and the state in Bangladesh: The politics of representing the poor. Development and Change, 30(2), 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00119.

Young, L., & Soroka, S. (2012). Affective news: The automated coding of sentiment in political texts. Political Communication, 29(2), 205–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2012.671234.

Yusuf, H. (2011). Conspiracy fever: The US, Pakistan and its media. Survival, 53(4), 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2011.603564.

Acknowledgements

Earlier drafts of this paper were presented at the 2018 Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action (ARNOVA) and the 2017 International Studies Association (ISA) conferences. Financial support for this research was provided by the Department of Political Science at the University of Washington. I would like to thank Aseem Prakash, John Wilkerson, David Suarez and Yusri Supiyan for their extremely helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Summary of Covariates

No | Yes | |

|---|---|---|

Negative | 368 | 288 |

Education | 529 | 127 |

Health | 565 | 91 |

Security | 529 | 127 |

Women rights | 500 | 156 |

Public accountability | 416 | 240 |

Government resistance | 563 | 93 |

Doing good | 406 | 250 |

Protest | 615 | 41 |

Local NGOs | 28 | 628 |

International NGOs | 628 | 28 |

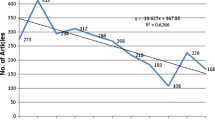

Appendix 2: Number of Articles by Year

Year | 1993 | 1994 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Articles | 51 | 67 | 7 | 51 | 14 | 12 | 123 | 60 | 74 | 64 | 33 | 100 |

Appendix 3: Coding Scheme

Introduction

As a coder, you will be given data from a single newspaper article and will be asked to decide whether or not the article is framing NGOs negatively. You will be asked to choose the topic that best represents how NGOs are being framed. You will receive the text of the article.

Once you determine what kind of frame exists in the newspaper article, you will code the article based on three categories:

-

1.

Sentiment (0: Not Negative; 1: Negative)

-

2.

Frame (DG: Doing Good, PA: Public Accountability, GR: Government Resistance, P: Protest)

Details on How to Code Each Category

Sentiment Analysis (0: Non-Negative; 1: Negative)

If an article is mostly neutral, and then portrays some part of the article as negative, code it as negative.

If the article is portraying NGOs positively, and then portrays NGOs negatively in another part of the article, count the amount of lines for positive and negative sentiment. If the number of lines for negative sentiment is more, code it as negative. If the number of lines for positive sentiment is more, code it as non-negative.

For an individual article to be scored a 1 (Negative) on this category, it must portray the NGOs negatively in the article.

Some examples, but not all, are the following:

Negative:

-

1.

NGOs are portrayed as ineffective.

-

2.

NGOs are portrayed as tools of foreign donors.

-

3.

NGOs are portrayed as corrupt.

-

4.

NGOs are portrayed as destroying local customs.

-

5.

NGOs are portrayed as not able to achieve their aims and programs successfully.

-

6.

NGOs are portrayed as being controlled by foreign donors. Example: Funding to NGOs gives donors control over NGOs’ activities.

-

7.

NGOs impose foreign agenda over the local population.

-

8.

Government is trying to control NGOs’ activities because of their foreign linkages.

-

9.

Government is trying to control NGOs’ activities because some of them may be involved in terrorism.

-

10.

NGOs are threatening Islam.

Non-Negative: NGOs are either portrayed neutral or positive

Neutral:

-

1.

NGOs are not neither portrayed negatively or positively.

-

2.

Goods are stolen from an NGO’s office.

Positive: NGOs are portrayed positively

Examples:

-

1.

Helping local communities by promoting education, health, etc.

-

2.

Protesting Human Rights abuses by the state.

-

3.

Acting as experts on socioeconomic issues.

Frames:

Read the article and come up with the best frame that explains the article. If there are more than two frames, count the number of lines for the frame. If the number of lines for one frame is more, then code that frame as the mainframe.

If the number of lines for each frame is equal, then look at heading of the article and code the article according to the frame present in the headlines. Look at the main headline to find the main frame.

Doing Good: Focuses on important, productive work that NGOs are doing in recognizing and reducing societal problems.

Examples:

-

1.

NGOs are providing free education.

-

2.

NGOs are providing relief aid.

-

3.

NGOs discussed issues of children rights.

-

4.

NGOs conducted a rally to raise funds for running schools.

Protest: NGOS speaking out against government or business activity that they deem unethical, harmful, irresponsible, illegal, or threatening. For protest frame, the protest has to be a physical protest.

Examples:

-

1.

NGOs protested the infringement of human rights by the government by holding a vigil.

-

2.

NGOs asked the government to fulfill its promises of providing free education by holding a protest on the road.

-

3.

NGOs spoke out against rampant child labor issues in Pakistani society by holding a press conference.

Public Accountability: Articles that question NGO activity, specifically concerning issues such as corruption, accountability, and poor management.

Examples:

-

1.

NGOs are corrupt.

-

2.

NGOs are driven by western donor agenda.

-

3.

NGOs waste resources.

-

4.

NGOs are ineffective.

-

5.

NGOs have not been able to successfully achieve their aims or programs.

-

6.

NGOs are involved in doing business and making money instead of serving humanity.

-

7.

NGOs are against Islamic values.

Expert: Articles in which NGOs are interviewed for their view on a subject or provided information.

Examples:

-

1.

Save the Children representative talked about the issue of children rights in Pakistan.

-

2.

The NGO representative talked about the challenges of education faced by Pakistan today.

Government Resistance: Government is portrayed as attempting to curb or restricting NGOs’ activities.

Examples:

-

1.

The Government is taking steps to force all NGOs to register.

-

2.

Government has closed the headquarters of Save the Children.

-

3.

Government has asked the NGOs’ officials to leave the country.

-

4.

If there is any mention of government restriction or new laws about government regulation, then code it as government resistance.

-

5.

If there is any mention of government restriction or new laws about government regulation, then code it as government resistance.

None: An article that does not fit any of the frames above.

Examples:

-

1.

NGO had goods stolen.

-

2.

Article talks about charity but does not focus on NGOs.

Appendix 4: Number of Articles by Newspaper

Newspaper | Number | |

|---|---|---|

1 | Newspaper Name Not Given/Clear | 178 |

2 | Al Akhbar | 10 |

3 | Ausaf | 14 |

4 | Daily Express | 1 |

5 | Dawn | 50 |

6 | Frontier Post | 33 |

7 | Jang | 29 |

8 | Jasarat | 8 |

9 | Khabrain | 10 |

10 | Nawa-i-waqt | 43 |

11 | Pakistan Observer | 26 |

12 | Pakistan Times | 29 |

13 | The Muslim | 37 |

14 | The Nation | 66 |

15 | The News | 122 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wasif, R. Does the Media’s Anti-Western Bias Affect its Portrayal of NGOs in the Muslim World? Assessing Newspapers in Pakistan. Voluntas 31, 1343–1358 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00242-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00242-5