Abstract

Although coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is primarily a respiratory disease, the kidney may be among the target organs of infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2). Independently of baseline kidney function, acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication of COVID-19, associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Most frequently, COVID-19 causes acute tubular necrosis; however, in some cases, collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and direct viral tropism of the kidneys have also been documented. AKI secondary to COVID-19 has a multi-factorial origin. Even mild impairment of renal function is an independent risk factor for COVID-19 infection, hospitalisation and mortality. Dialysis patients also carry an increased risk of other severe COVID-related complications, including arrhythmias, shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute heart failure. In such patients, COVID-19 may even present with atypical clinical symptoms, including gastrointestinal disorders and deterioration of mental status. More research is needed on the exact effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the kidneys. Finally, it remains to be proven whether the outcome of patients with kidney disease may be improved with anticipated vaccination programmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Although coronavirus infectious disease (COVID-19) is primarily a respiratory disease, the kidney may be among the target organs of infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2). Data on the kidney involvement of COVID-19 patients are still very scarce. However, as more patients are infected worldwide, our understanding of the disease is rapidly evolving.

Independently of baseline kidney function, acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication of COVID-19 [1]. Several pathogenic mechanisms have been implicated, including critical hypoxia, inflammation and sepsis, haemodynamic changes, acute cardiorenal syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, mitochondrial injury, endothelial dysfunction, microembolism, kidney infarction and use of nephrotoxic drugs (Table 1) [1]. The frequency of AKI reaches 9% in hospitalised patients with COVID-19, but it has been reported to be as high as 68% [2] among critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit. In the majority of cases, COVID-19 associated AKI is mild to moderate and is manifested as an increase in serum creatinine, haematuria and/or proteinuria [3, 4], while electrolyte abnormalities such as hyperkalemia may be also be seen [5]. Among in-patients, the most common cause of AKI is acute tubular necrosis, which is associated with a nearly sixfold mortality [6]. Of note, recent data suggest a significant reduction in the frequency of AKI from spring to autumn [7]. This may possibly be attributed to the rising proportion of younger patients with fewer comorbidities managed with non-invasive positive pressure ventilation rather than intubation during this second pandemic [7].

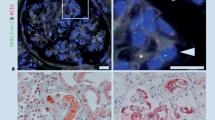

However, data from post-mortem kidney autopsies showed that COVID-19 may, in addition to acute tubular injury, also cause glomerulonephritis, including collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and direct viral tropism of the kidneys [8]. Collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is rare, typically presents with nephrotic-range proteinuria, and is associated with phenotypic changes in the podocytes and the Apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) genotype [4]. The presence of virus-like particles in autopsy samples from COVID-19 patients with AKI has led to the hypothesis that the virus may enter kidney tubule epithelial cells and podocytes via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors and cause direct nephrotoxicity [9].

AKI is associated with high mortality and morbidity. A recent meta-analysis of 58 studies including 13,452 patients has shown that AKI requiring kidney replacement therapy (KRT) is common among hospitalised, critically ill patients (about 5–9%) and increases the overall hospital mortality rate (Odds Ratio 3.43, 95% Confidence Interval 2.02–5.85) [3, 10]. Of note, nearly all of the patients who required KRT were mechanically ventilated. Although the majority of patients who recover from AKI due to COVID-19 regain their kidney function, one-third of them run the risk of remaining on dialysis at discharge [11]. Several conditions have been recognised as risk factors for AKI requiring KRT [11, 12]. These include pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes mellitus, hypertension, male gender, high body-mass index, increased severity of hypoxia on admission, need for mechanical ventilation, and high interleukin-6 levels [11, 12]. In turn, AKI increases mortality and contributes to long-term complications such as CKD, leading to prolonged hospitalisation and high healthcare costs [1]. Given that there is no specific therapy, prevention and treatment strategies of AKI are mainly supportive [11, 12]. Individualised management of volume status and correction of volume depletion is of the utmost importance. Furthermore, lung-protective ventilation and cytokine removal strategies may decrease the risk of AKI and prevent its complications by limiting the cytokine storm and the ventilator-derived hemodynamic effects on the kidney [11, 12]. Due to the hypercoagulation state of the infection, continuous KRT should be carried out with regional citrate anticoagulation [13].

CKD patients at various stages (both pre-dialysis and dialysis) have an increased risk of COVID-19 infection. The true prevalence and implications of COVID-19 in CKD patients remain under investigation, but a recent meta-analysis reported a pooled prevalence of 5.2% of pre-existing CKD in a cohort of 17,391 COVID-19 patients [5]. Among patients infected with COVID-19, CKD and hypertension were associated with a threefold increase in infection severity and a twofold increase in mortality [10, 14]. The prevalence of prior CKD was 9 times higher in hospitalised patients with severe infection, compared with those having mild infection [14]. CKD patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of virus infection should be closely monitored and early admitted to the hospital if needed.

Kidney transplant recipients might be extremely vulnerable to COVID-19 infection as they are immunosuppressed and commonly characterised by increased comorbidity. The Spanish Registry prospectively included 1011 kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19, followed until death or recovery and reported that advanced age, pneumonia and kidney transplant performed in the last six months before SARS-CoV-2 infection were independent predictors of mortality, whereas gastrointestinal symptoms were associated with low mortality rates [15]. Compared to the first (March–June 2020), in the second pandemic wave (July–December 2020), kidney transplant recipients infected with COVID-19 were significantly younger with reduced overall mortality rates. A careful and tailored therapeutic approach regarding immunosuppressive drugs is needed in kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19. It should consider both severity of the infection and potential interactions between antiviral and immunosuppressive treatment, to balance the risks of graft rejection/loss vs, the complications of the infection [16].

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are anti-hypertensive agents frequently prescribed in CKD patients. Granted that ACE2 is a receptor used by the SARS COV-2 virus to enter host cells, there was an initial concern that infected patients receiving these drugs might be at increased risk for disease severity and mortality [17]. However, since this hypothesis remained unproven in large cohort studies and systematic reviews, joint guideline panels suggest that the use of these agents should not be discontinued in stable CKD patients and only stopped in the event of hypotension or severe hyperkalaemia [18, 19].

Although at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen were widely used, shortly thereafter, it was hypothesised that ibuprofen might facilitate COVID-19 infection and increase the risk of transmission, through upregulation of ACE2 expression [20]. An additional concern raised by several researchers was that short-term treatment with NSAIDs in lung infections might amplify the risk of bacterial complications [21, 22] and it has been suggested that the use of these drugs might lead to superinfection during SARS-CoV2 infection and thus should be avoided. However, Vaja et al. performed a systematic review of 8 studies and 44,140 patients treated with NSAIDs during acute lower respiratory tract infections and found a non-significant trend towards a decrease in mortality and increase in pleuro-pulmonary complications. Since available data were highly heterogeneous and of poor quality and all studies had a severe risk of bias, the authors concluded that these results should be interpreted with caution [23]. In agreement with this finding, another multicentre, observational study with a small sample size also failed to show any association between NSAIDs and mortality risk [24], whereas a recent meta-analysis including three studies and 2414 patients with SARS-CoV2 infection failed to show any difference in mortality among patients treated with NSAIDs and those that did not use NSAIDs [25].

A further major concern regarding the use of these drugs in COVID-19 patients is that both selective and non-selective NSAIDs have been repeatedly associated with increased risk for developing AKI [26] and venous thromboembolism [27], conditions that might affect the clinical course of COVID-19 infection. There is a controversy regarding the use of NSAIDs and the worsening of respiratory complications in COVID-19 infected patients; however, there is strong evidence linking NSAIDs with AKI. Since there is a much safer therapeutic alternative with paracetamol at recommended doses, NSAIDs should be avoided in these patients.

Importantly, during this pandemic, patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) who are referred for initiation of KRT should undergo all necessary selective procedures (arteriovenous fistulae or graft, or peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter or central venous catheter) as scheduled without delays [28]. Conversely, it is recommended that regular monitoring of CKD patients should be preferably done via remote and not by in-person visits [28]. Compared to pre-dialysis CKD, dialysis patients have an increased risk for infection and in-hospital mortality [29]. The frequency of COVID-19 infection in ESKD patients undergoing haemodialysis (HD) varies from 1 to 22% [10, 30, 31], but it typically reflects the overall frequency among the corresponding general population.

Compared to PD patients, those undergoing HD have a fourfold increased incidence rate of COVID-19 infection [32]. This could be attributed to the fact that PD is a home-dialysis modality, whereas HD is conducted in dialysis outpatient centres, where viral transmission is commoner [32]. ESKD patients are extremely vulnerable to severe virus infection, due not only to kidney impairment but also due to advanced age and high prevalence of comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus [33]. The overall mortality rate of hospitalised HD patients varies among studies from 20 to 50% [10, 29]. When compared with propensity-score matched controls, HD patients have a 20-fold increased risk for 28-day mortality risk, male gender and old age being the strongest risk factors associated with death [34]. This risk difference among genders could be attributed to genetic, hormonal and behavioural factors. In HD patients hospitalised for COVID-19, C-reactive protein was the strongest laboratory predictor of mortality with an area under the curve of 0.90 and outperformed procalcitonin [35].

In addition to mortality, HD patients carry an increased risk of other severe COVID-related complications, including arrhythmias, shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute heart failure [33]. Compared with patients having normal kidney function, HD patients may present different clinical manifestations, including gastrointestinal disorders and deterioration of mental status, rather than fever or respiratory symptoms [29]. During the first wave of the pandemic, no more than 9% of in the United States and about 20% in the United Kingdom of adult HD patients formed antibodies for SARS-COV-2 [30], while 90% were asymptomatic [36]. Several international societies and organisations, including the International Society of Nephrology [37], the American Society of Nephrology [38] and the European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association [39] have published information, resources and interim recommendations on CKD, AKI and HD in the new era. A further emerging issue is the potential renoprotective action of sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in subjects with mild to moderate COVID-19 [40], which, however, is still under investigation.

In conclusion, we are beginning to learn that the kidney is one of the target organs for COVID-19 [1]. AKI is a frequent complication of the infection, associated with worse clinical outcomes [3, 10]. Patients with any degree of renal impairment are at increased risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalisation and mortality [5, 10, 14]. Whether these outlooks may be improved with expected vaccination programmes is clearly interesting but needs to be investigated.

References

Kellum JA, van Till JO, Mulligan G (2020) Targeting acute kidney injury in COVID-19. Nephrol Dial Transplant 35(10):1652–1662

Chan L, Chaudhary K, Saha A, Chauhan K, Vaid A, Baweja M, Campbell K, Chun N, Chung M, Deshpande P, Farouk SS, Kaufman L, Kim T, Koncicki H, Lapsia V, Leisman S, Lu E, Meliambro K, Menon MC, Rein JL, Sharma S, Tokita J, Uribarri J, Vassalotti JA, Winston J, Mathews KS, Zhao S, Paranjpe I, Somani S, Richter F, Do R, Miotto R, Lala A, Kia A, Timsina P, Li L, Danieletto M, Golden E, Glowe P, Zweig M, Singh M, Freeman R, Chen R, Nestler E, Narula J, Just AC, Horowitz C, Aberg J, Loos RJF, Cho J, Fayad Z, Cordon-Cardo C, Schadt E, Levin MA, Reich DL, Fuster V, Murphy B, He JC, Charney AW, Bottinger EP, Glicksberg BS, Coca SG, Nadkarni GN (2020) Acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.04.20090944

Robbins-Juarez SY, Qian L, King KL, Stevens JS, Husain SA, Radhakrishnan J, Mohan S (2020) Outcomes for patients with COVID-19 and acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int Rep 5(8):1149–1160

Kissling S, Rotman S, Gerber C, Halfon M, Lamoth F, Comte D, Lhopitallier L, Sadallah S, Fakhouri F (2020) Collapsing glomerulopathy in a COVID-19 patient. Kidney Int 98(1):228–231

Kunutsor SK, Laukkanen JA (2020) Renal complications in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med 52(7):345–353

Chen Y-T, Shao S-C, Hsu C-K, Wu I-W, Hung M-J, Chen Y-C (2020) Incidence of acute kidney injury in COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 24(1):1–4

Bowe B, Cai M, Xie Y, Gibson AK, Maddukuri G, Al-Aly Z (2020) Acute kidney injury in a national cohort of hospitalized US veterans with COVID-19. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16(1):14–25. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.09610620

Santoriello D, Khairallah P, Bomback AS, Xu K, Kudose S, Batal I, Barasch J, Radhakrishnan J, D’Agati V, Markowitz G (2020) Postmortem kidney pathology findings in patients with COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol 31(9):2158–2167. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2020050744

Su H, Yang M, Wan C, Yi L-X, Tang F, Zhu H-Y, Yi F, Yang H-C, Fogo AB, Nie X (2020) Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int 98(1):219–227

Zhou S, Xu J, Xue C, Yang B, Mao Z, Ong AC (2020) Coronavirus-associated kidney outcomes in COVID-19, SARS, and MERS: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Ren Fail 43(1):1–15

Gupta S, Coca SG, Chan L, Melamed ML, Brenner SK, Hayek SS, Sutherland A, Puri S, Srivastava A, Leonberg-Yoo A, Shehata AM, Flythe JE, Rashidi A, Schenck EJ, Goyal N, Hedayati SS, Dy R, Bansal A, Athavale A, Nguyen HB, Vijayan A, Charytan DM, Schulze CE, Joo MJ, Friedman AN, Zhang J, Sosa MA, Judd E, Velez JCQ, Mallappallil M, Redfern RE, Bansal AD, Neyra JA, Liu KD, Renaghan AD, Christov M, Molnar MZ, Sharma S, Kamal O, Boateng JO, Short SAP, Admon AJ, Sise ME, Wang W, Parikh CR, Leaf DE, S-C Investigators (2021) AKI treated with renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol 32(1):161–176. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2020060897

Hirsch JS, Ng JH, Ross DW, Sharma P, Shah HH, Barnett RL, Hazzan AD, Fishbane S, Jhaveri KD, C-RC Northwell, C-RC Northwell Nephrology (2020) Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int 98(1):209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006

Ronco C, Reis T, Husain-Syed F (2020) Management of acute kidney injury in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med 8(7):738–742

Henry BM, Lippi G (2020) Chronic kidney disease is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Int Urol Nephrol 52(6):1193–1194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-020-02451-9

Villanego F, Mazuecos A, Pérez-Flores IM, Moreso F, Andrés A, Jiménez-Martín C, Molina M, Canal C, Sánchez-Cámara LA, Zárraga S (2021) Predictors of severe COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients in the different epidemic waves: analysis of the Spanish Registry. Am J Transplant 21(7):2573–2582

Angelico R, Blasi F, Manzia TM, Toti L, Tisone G, Cacciola R (2021) The management of immunosuppression in kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19 disease: an update and systematic review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas). https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57050435

Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X (2020) COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol 17(5):259–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5

de Simone G (2020) Position statement of the ESC council on hypertension on ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. European Society of Cardiology

de la Cruz A, Ashraf S, Vittorio TJ, Bella JN (2020) COVID-19 and renin-angiotensin system modulators: what do we know so far? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 18(11):743–748

Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M (2020) Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 8(4):e21

Micallef J, Soeiro T, Annie-Pierre JB (2020) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pharmacology, and COVID-19 infection. Therapies 75(4):355–362

Lund LC, Reilev M, Hallas J, Kristensen KB, Thomsen RW, Christiansen CF, Sørensen HT, Johansen NB, Brun NC, Voldstedlund M (2020) Association of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and adverse outcomes among patients hospitalized with influenza. JAMA Netw Open 3(7):e2013880–e2013880

Vaja R, Chan JSK, Ferreira P, Harky A, Rogers LJ, Gashaw HH, Kirkby NS, Mitchell JA (2021) The COVID-19 ibuprofen controversy: a systematic review of NSAIDs in adult acute lower respiratory tract infections. Br J Clin Pharmacol 87(3):776–784

Bruce E, Barlow-Pay F, Short R, Vilches-Moraga A, Price A, McGovern A, Braude P, Stechman MJ, Moug S, McCarthy K (2020) Prior routine use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and important outcomes in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. J Clin Med 9(8):2586

Kow CS, Hasan SS (2021) The risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19 with pre-diagnosis use of NSAIDs: a meta-analysis. Inflammopharmacology 29:1–4

Ungprasert P, Cheungpasitporn W, Crowson CS, Matteson EL (2015) Individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Intern Med 26(4):285–291

Schmidt M, Christiansen C, Horvath-Puho E, Glynn R, Rothman K, Sørensen H (2011) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost 9(7):1326–1333

Bruchfeld A (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic: consequences for nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-020-00381-4

Flythe JE, Assimon MM, Tugman MJ, Chang EH, Gupta S, Shah J, Sosa MA, Renaghan AD, Melamed ML, Wilson FP, Neyra JA, Rashidi A, Boyle SM, Anand S, Christov M, Thomas LF, Edmonston D, Leaf DE, S-C Investigators (2021) Characteristics and outcomes of individuals with pre-existing kidney disease and COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 77(2):190-203.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.09.003

Anand S, Montez-Rath M, Han J, Bozeman J, Kerschmann R, Beyer P, Parsonnet J, Chertow GM (2020) Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in a large nationwide sample of patients on dialysis in the USA: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 396(10259):1335–1344

Couchoud C, Bayer F, Ayav C, Béchade C, Brunet P, Chantrel F, Frimat L, Galland R, Hourmant M, Laurain E (2020) Low incidence of SARS-CoV-2, risk factors of mortality and the course of illness in the French national cohort of dialysis patients. Kidney Int 98(6):1519–1529

Zeng X, Huang X, Xu L, Xiao J, Gu L, Wang Y, Tuo Y, Fang X, Wang W, Li N (2020) Clinical outcomes of dialysis patients with COVID-19 in the initial phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int Urol Nephrol 53(2):353–357

Valeri AM, Robbins-Juarez SY, Stevens JS, Ahn W, Rao MK, Radhakrishnan J, Gharavi AG, Mohan S, Husain SA (2020) Presentation and outcomes of patients with ESKD and COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol 31(7):1409–1415

Jager KJ, Kramer A, Chesnaye NC, Couchoud C, Sánchez-Álvarez JE, Garneata L, Collart F, Hemmelder MH, Ambühl P, Kerschbaum J (2020) Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int 98(6):1540–1548

Shang W, Li Y, Li H, Li W, Li C, Cai Y, Dong J (2021) Correlation between laboratory parameters on admission and outcome of COVID-19 in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol 53(1):165–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-020-02646-0

Clarke C, Prendecki M, Dhutia A, Ali MA, Sajjad H, Shivakumar O, Lightstone L, Kelleher P, Pickering MC, Thomas D (2020) High prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection in hemodialysis patients detected using serologic screening. J Am Soc Nephrol 31(9):1969–1975

Naicker S, Yang C-W, Hwang S-J, Liu B-C, Chen J-H, Jha V (2020) The novel coronavirus 2019 epidemic and kidneys. Kidney Int 97(5):824–828

American Society of Nephrology (ASN). Recommendations on the care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and kidney failure requiring renal replacement therapy. https://www.asn-online.org/g/blast/files/AKI_COVID19_Recommendations_Document_03.21.2020.pdf. Accessed 23 Dec 2020

European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA). ERA-EDTA information for nephrologists and other professionals on prevention and treatment of COVID-19 infections in kidney patients. https://www.era-edta.org/en/covid-19-news-and-information/. Accessed 23 Dec 2020

Papachristou S, Penlioglou T, Stoian AP, Papanas N (2020) COVID-19 and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: no fear to attempt? Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1235-5617

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liakopoulos, V., Roumeliotis, S., Papachristou, S. et al. COVID-19 and the kidney: time to take a closer look. Int Urol Nephrol 54, 1053–1057 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-02976-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-02976-7