Abstract

Using a randomized controlled trial design, we examine the effects of savings incentives (match rate 1:1 versus 1:2) with mentorship and financial trainings on child poverty among 1383 orphaned children (mean age 12.7 years at baseline) in rural Uganda. Given the difficulty to capture child poverty using monetary measures, we use a multidimensional class of poverty that captures four dimensions: health, assets, housing, and behavioral risks. Results show that children in treatment groups experienced reductions in poverty incidence by 10 percentage points (or deprivation score by 8 percent) relative to control group counterparts at four years post-baseline, and a higher savings incentive led to stronger effects. Further, children in treatment groups were more likely to escape the poverty trap. Finally, we assess the robustness of these results to various weighting structures. This study offers a unique evidence on effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention targeting children in alleviating poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A child is defined as an individual aged 18 and below at baseline. All participants in the last two grades of primary school were under the age of 18 at baseline.

Detailed power analysis of this study can be found in Wang et al. (2018). Overall, results from a power analysis indicated that this study could detect small to small-medium effects.

The account is held by the caregiver and the child because, according to the contractual laws in Uganda, a child cannot individually hold a binding contract. Nevertheless, no withdrawals can be made without the child’s approval and signature.

It is important to note that with funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the Bridges to the Future study has been adapted under the Suubi4Her study (1 R01 MH113486-01), specifically focused on younger girls (ages 14–17)—regardless of whether they are orphaned or not orphaned. Preliminary findings from the adapted Suubi4Her intervention indicate similar positive findings in improving educational, behavioral, and mental health outcomes as shown in the Bridges to the Future study (Ssewamala et al., 2018).

We further test whether the attrition status is associated with observable characteristics. We run a regression model with attrition status at Year 4 as the outcome and we included the following predictors: treatment status (Control (ref.), Bridges, and Bridges PLUS), observable characteristics (double orphan status, primary caregiver, age, female, years living in the households, household size, number of children, employment status of the caregiver), and the interactions between each treatment status and each observable characteristic. Among all 20 independent variables included in the analysis, coefficients of 19 variables are not statistically significant, except for the interaction between female and Bridges PLUS (β = 0.069, SE = 0.027, p-value = 0.011) is significant, indicating that female participants in the Bridges PLUS group were more likely to drop out from the study.

This study did collect information on self-rated health. Due to the concern that children may change their reference groups over time (e.g., children who benefited from the intervention more may have better educational attainment; hence they may have a different reference group when they respond to the self-rated health question), we opted not to include this measure.

This study did collect information on social participation at school. However, in longitudinal analysis, some children were no longer in school during later follow-ups, making this measure on social participation non-applicable to many children in later time points.

In Appendix Fig. 3, we present the multidimensional poverty index (MPI) patterns using varying cutoffs. In Appendix Table 10, we present our main findings using alternative cutoffs: 0/4 and 2/4 of all indicators. When the poverty cutoff is 0/4 (a child is not deprived in any indicator), the average proportion of MPI poor children is 99.8% at baseline and 97.4% at Year 4. When the poverty cutoff is 2/4 (a child is deprived in a total of two dimensions or six indicators), the average proportion of MPI poor children is 3.8% at baseline and 2.1% at Year 4. This suggests that 1/4 is a better cutoff that capture variations in multidimensional poverty transitions.

Average of weighted deprivation scores among the poor.

The adjusted headcount ratio (M0) is calculated as H x A. M0 is “the sum of the weighted deprivations that the poor (and only the poor) experience, divided by the total population” (Alkire & Santos, 2014).

We also experimented with the three-level multilevel model used in Wang et al.’s (2018) paper. The results are presented in Appendix Table 9 and are similar to our main findings in Table 6. We also experimented with ANCOVA analysis accounting for baseline differences in outcomes, and the results are more robust compared to main findings in Table 6 (see Appendix Table 11).

We also conducted sensitivity analyses controlling for additional characteristics, and the results are presented in Appendix Table 8. Model 1 presents the results from the same model as in the model presented in Table 6 while controlling for baseline characteristic differences across the three groups: double-orphan status and relationship to the primary caregiver. Model 2 presents the results from the same model as Model 1 while additionally controlling for characteristics that differ by attrition status: age, gender, years living in the household, and primary caregiver. Model 3 presents results from the same model as in Model 2 while additionally controlling for other characteristics, such as household size, number of children, and caregiver employment status. The results are qualitatively the same as the main results presented in Table 6.

We further tested the association between school characteristics and the three study groups. We found that the schools do not differ significantly by district, nearest town, distance to the main road, school size, and educational performance (Wang et al., 2018).

Although the differences in coefficients between the Bridges and Bridges PLUS groups were not statistically different, when we restricted the analyses to respondents aged 18 or below, the difference between Bridges and Bridges PLUS children was statistically significant.

We also experimented with allowing a wider range of weights by only ruling out any combination that gave a single dimension less than 10% or more than 90% weight; which left us with 455 different weighting structures. We present the results from this analysis in Appendix Fig. 4

Although the poverty incidence and deprivation score between Bridges and Bridges PLUS were not statistically significantly different from each other, when we restrict the sample to children aged 18 and below, the intervention effect was statistically significantly stronger for Bridges PLUS children than Bridges children.

References

Adato, M., Carter, M. R., & May, J. (2006). Exploring poverty traps and social exclusion in South Africa using qualitative and quantitative data. The Journal of Development Studies, 42(2), 226–247.

Ahammed, I. (2009). A Case Study on Financial Services for Street Children: Padakhep. In For the Making Cents International Conference, Washington, DC.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of public economics, 95(7–8), 476–487.

Alkire, S., Dorji, L., Gyeltshen, S., & Minten, T. (2016). Child Poverty in Bhutan: Insights from multidimensional child poverty index and qualitative interviews with poor children. Thimphu: National Statistics Bureau.

Alkire, S., Jindra, C., Robles, G., & Vaz, A. (2017). Children’s multidimensional poverty: disaggregating the global MPI. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI) Briefing 46.

Alkire, S., Roche, J. M., Ballon, P., Foster, J., Santos, M. E., & Seth, S. (2015). Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis. Chapter 7: Data and analysis. Oxford University Press, USA.

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2014). Measuring acute poverty in the developing world: Robustness and scope of the multidimensional poverty index. World Development, 59, 251–274.

Atkinson, A. B. (2017). Monitoring global poverty: Report of the commission on global poverty. World Bank.

Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Das, N., Gulesci, S., Rasul, I., & Sulaiman, M. (2017). Labor markets and poverty in village economies. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 811–870.

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Chattopadhyay, R., & Shapiro, J. (2016). The Long term Impacts of a “Graduation” Program: Evidence from West Bengal. Retrieved from: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/publications/92_12_The-Long-Impact-of-Graduation-Program_TUP_Sept2016.pdf

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Goldberg, N., Karlan, D., Osei, R., Parienté, W., Shapiro, J., Thuysbaert, B., & Udry, C. (2015). A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries. Science, 348(6236), 1260799.

Bastos, A., & Machado, C. (2009). Child poverty: a multidimensional measurement. International Journal of Social Economics, 36(3), 237–251.

Blattman, C., Green, E. P., Jamison, J., Lehmann, M. C., & Annan, J. (2016). The returns to microenterprise support among the Ultrapoor: A field experiment in Postwar Uganda. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 8(2), 35–64.

Curley, J., Ssewamala, F., & Han, C. K. (2010). Assets and educational outcomes: Child Development Accounts (CDAs) for orphaned children in Uganda. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(11), 1585–1590.

de Milliano, M. and I. Plavgo (2014). Analysing Child poverty and deprivation in sub-Saharan Africa: CC-MODA – Cross Country Multiple Overlapping Deprivation Analysis, Innocenti Working Paper No.2014–19, UNICEF Office of Research, Florence.

de Neubourg, C., Chai, J., de Milliano, M., Plavgo, I., & Wei, Z. (2012). Cross-Country MODA Study. Working Paper 2012–05, UNICEF Office of Research, Florence.

Deshpande, R., & Zimmerman, J. (2010). Savings accounts for young people in developing countries: Trends in practice. Enterprise Development and Microfinance, 21(4), 275–292.

DuBois, D. L., Portillo, N., Rhodes, J. E., Silverthorn, N., & Valentine, J. C. (2011). How effective are mentoring programs for youth? A systematic assessment of the evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(2), 57–91.

Earls, F., & Visher, C. A. (1997). Project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods: a research update. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

Erulkar, A., & Chong, E. (2005). Evaluation of a savings & micro-credit program for vulnerable young women in Nairobi. Population Council.

Fitts, W. H., & Warren, W. L. (1996). Tennessee self-concept scale: TSCS-2 (p. 118). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Gordon, D. (2003). Child poverty in the developing world. Policy Press.

Han, C.-K., Ssewamala, F. M., & Wang, J.S.-H. (2013). Family economic empowerment and mental health among AIDS-affected children living in AIDS-impacted communities: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in southwestern Uganda. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(3), 225–230.

Harrison, A., Newell, M. L., Imrie, J., & Hoddinott, G. (2010). HIV prevention for South African youth: which interventions work? A systematic review of current evidence. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 102.

Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the social support scale for children. University of Denver.

Hilton, D., Mahmud, K. T., Kabir, S., Mohammad, G., & Parvez, A. (2016). Does Training Really Matter to the Rural Poor Borrowers in Bangladesh? A Case Study on BRAC. Journal of International Development, 28(7), 1092–1103.

Jamison, J. C., Karlan, D., & Zinman, J. (2014). Financial education and access to savings accounts: Complements or substitutes? Evidence from Ugandan youth clubs (No. w20135). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jennings, L., Ssewamala, F. M., & Nabunya, P. (2016). Effects of Savings-led economic empowerment on HIV preventive practices among orphaned adolescents in rural Uganda: results from the Suubi-Maka randomized experiment. AIDS Care, 28(3), 273–282.

Jothilakshmi, M., Krishnaraj, R., & Sudeepkumar, N. K. (2009). Empowering the members of women SHGs in livestock farming through need-based trainings. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 19(2), 17–30.

Kaiser, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2016). Does financial education impact financial behavior, and if so, when. Discussion Papers of DIW Berlin.

Karimli, L., Ssewamala, F. M., & Neilands, T. B. (2014). Poor families striving to save for their children: Lessons from a randomized experimental design in Uganda. Social Service Review, 88(4), 658–694.

Karlan, D., Ratan, A. L., & Zinman, J. (2014). Savings by and for the Poor: A Research Review and Agenda. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(1), 36–78.

Kast, F., Meier, S., & Pomeranz, D. (2012). Under-savers anonymous: Evidence on self-help groups and peer pressure as a savings commitment device (No. w18417). National Bureau of Economic Research.

LoScuito, L., Rajala, A. K., Townsend, T. N., & Taylor, A. S. (1996). An outcome evaluation of Across Ages: An intergenerational mentoring approach to drug prevention. Journal of Adolescent Research, 11(1), 16–29.

Madrian, B. C. (2012). Matching Contributions and Savings Outcomes: A Behavioral Economics Perspective. NBER Working Paper Series, 18220.

Mahmud, K. T., Kabir, G. M. S., Islam, M. T., & Hilton, D. (2012). Impact of fishery training program on the living standard of the fishers: a case of community based fishery management project in Bangladesh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 22(2), 23–34.

Malaeb, B., & Uzor, E. (2017). Multidimensional Impact Evaluation: A Randomized Control Trial on Conflict-affected Women in Northern Uganda. Retrieved from: https://www.africaportal.org/publications/multidimensional-impact-evaluation-randomized-control-trial-conflict-affected-women-northern-uganda/

Matshalaga, N. R. (2002). Social dynamics of orphan care in the era of the HIV/AIDS pandemic: An insight of grandmothers' experiences in Zimbabwe. Syracuse University. Retrieved from: https://surface.syr.edu/soc_etd/28

Miller, M., Reichelstein, J., Salas, C., & Zia, B. (2015). Can you help someone become financially capable? A meta-analysis of the literature. The World Bank Research Observer, 30(2), 220–246.

Misha, F. A., Raza, W. A., Ara, J., & Van de Poel, E. (2018). How far does a big push really push? Mitigating ultra-poverty in Bangladesh. Economic Development and Cultural Change.

Moodie, M. L., & Fisher, J. (2009). Are youth mentoring programs good value-for-money? An evaluation of the Big Brothers Big Sisters Melbourne Program. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 41.

Nabunya, P., Ssewamala, F. M., Mukasa, M. N., Byansi, W., & Nattabi, J. (2015). Peer mentorship program on HIV/AIDS knowledge, beliefs, and prevention attitudes among orphaned adolescents: An evidence based practice. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 10(4), 345–356.

Noor, K. B. M., & Dola, K. (2010). Assessing impact of veterinary training on Malaysian farmers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 20(1), 33–50.

O’Prey, L., & Shepard, D. (2014). Financial education for children and youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aflatoun Working Paper, 2014. lc.

Radeny, M., Van den Berg, M., & Schipper, R. (2012). Rural poverty dynamics in Kenya: Structural declines and stochastic escapes. World Development, 40(8), 1577–1593.

Robano, V., & Smith, S. C. (2014). Multidimensional targeting and evaluation: General framework with an application to a poverty program in Bangladesh (Vol. 65, p. 3). OPHI Working Paper.

Roelen, K. (2017). Monetary and multidimensional child poverty: A contradiction in terms? Development and Change, 48(3), 502–533.

Roelen, K., Gassmann, F., & de Neubourg, C. (2010). Child poverty in Vietnam: Providing insights using a country-specific and multidimensional model. Social Indicators Research, 98(1), 129–145.

Rohe, W. M., Key, C., Grinstein-Weiss, M., Schreiner, M., & Sherraden, M. (2017). The impacts of Individual Development Accounts, assets, and debt on future orientation and psychological depression. Journal of Policy Practice, 16(1), 24–45.

Schaner, S. (2016). The persistent power of behavioral change: Long-run impacts of temporary savings subsidies for the poor (No. w22534). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Schreiner, M. (2005). Match rates, individual development accounts, and savings by the poor. Journal of Income Distribution, 13(3), 112–129.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press.

Shephard, D. D., Kaneza, Y. V., & Moclair, P. (2017). What curriculum? Which methods? A cluster randomized controlled trial of social and financial education in Rwanda. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 310–320.

Ssewamala, F. M., Karimli, L., Neilands, T. B., Wang, J.S.-H., Han, C.-K., Ilic, V., & Nabunya, P. (2016). Applying a family-level economic strengthening intervention to improve education and health-related outcomes of orphaned children: Lessons from a randomized experiment in southern Uganda. Prevention Science, 17, 134–143.

Ssewamala, F. M., Nabunya, P., Mukasa, N. M., Ilic, V., & Nattabi, J. (2014). Integrating a mentorship component in programming for care and support of AIDS-orphaned and vulnerable children: lessons from the Suubi and Bridges Programs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Global Social Welfare, 1(1), 9–24.

Ssewamala, F. M., Neilands, T. B., Waldfogel, J., & Ismayilova, L. (2012). The impact of a comprehensive microfinance intervention on depression levels of AIDS-orphaned children in Uganda. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(4), 346–352.

Ssewamala, F. M., Wang, J. S. H., Neilands, T. B., Bermudez, L. G., Garfinkel, I., Waldfogel, J., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Kirkbride, G. (2018). Cost-effectiveness of a savings-led economic empowerment intervention for AIDS-affected adolescents in Uganda: Implications for scale-up in low-resource communities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(1), S29–S36.

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Darling, N., Mounts, N. S., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1994). Over-time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development, 65(3), 754–770.

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., & Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63(5), 1266–1281.

Steinert, J. I., Zenker, J., Filipiak, U., Movsisyan, A., Cluver, L. D., & Shenderovich, Y. (2018). Do saving promotion interventions increase household savings, consumption, and investments in Sub-Saharan Africa? A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Development, 104, 238–256.

Trani, J. F., & Cannings, T. I. (2013). Child poverty in an emergency and conflict context: A multidimensional profile and an identification of the poorest children in Western Darfur. World Development, 48, 48–70.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). (2014). Uganda National Household Survey 2012/2013. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS.

UNICEF. (2006). Africa’s Orphaned and Vulnerable Generations: Children affected by AIDS. Retrieved: https://www.unicef.org/sowc06/pdfs/africas_orphans.pdf

UNICEF and the World Bank Group (2016). Ending Extreme Poverty: A Focus on Children. Retrieved https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_92826.html#.

United Nations. (2018). Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300

Wang, J.S.-H., Ssewamala, F. M., Neilands, T., Bermudez, L. G., Garfinkel, I., Waldfogel, J., Brooks-Gunn, J., & You, J. (2018). Effects of financial incentives on saving outcomes and material well-being: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Uganda. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37(3), 602–629.

World Bank. (2016). Poverty. Retrieved: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview

Acknowledgements

The Bridges to the Future study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) under Award Number 1R01HD070727-01, PI: Fred M. Ssewamala. The study received Institutional Review Board approvals from Columbia University (IRB # AAAI1950) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (Ref. SS2586). The authors acknowledge the support of the 48 public schools and local institutions, including Reach the Youth-Uganda and the Diocese of Masaka in Western Uganda that engaged in this study. We are also thankful to the children and their caregivers who participated in the study. Malaeb acknowledges the support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)’s Grant No. ES/N01457X/1 on evaluating integrated policies to reduce multidimensional poverty.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The content and views expressed in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD, the ESRC, or the institutions to which they belong.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16 and

17.

See Figs.

3 and

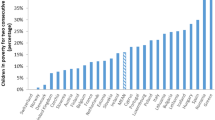

Robustness Check: Effect Sizes Across Various Random Weighting Structure (10–90). Note: The X-axis for the MPI poor outcome: differences in MPI poverty incidence from baseline to a given time point (range: − 1 to 1). The X-axis for the C vector outcome: differences in deprivation scores from baseline to a given time point (range: -1 to 1). Bars represent the 95% confidence interval

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J.SH., Malaeb, B., Ssewamala, F.M. et al. A Multifaceted Intervention with Savings Incentives to Reduce Multidimensional Child Poverty: Evidence from the Bridges Study (2012–2018) in Rural Uganda. Soc Indic Res 158, 947–990 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02712-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02712-9