Abstract

Wage penalties in overqualified employment are well documented, but little is known regarding the underlying mechanisms. Drawing on new methods to measure the mismatch between jobs and qualifications, we test two explanations: formal overqualification and a mismatch of occupational skills, which have so far not been analysed. Using the National Educational Panel Study survey that is linked to German administrative data, we can objectively measure both types of mismatch. By using fixed-effects models, we confirm that overqualification is associated with a wage loss of approximately 5%, which indicates penalties when working at a lower requirement level. We find that some of this wage loss can be explained by a mismatch of skills between the current and training occupation. Further analyses show that mismatches of occupational skills explain the wage loss of formal overqualification for employees with vocational training. For academics, the two types of mismatch are unrelated. We conclude that, because of occupational boundaries and more specific occupational skills, vocationally trained people who are overqualified more often work in jobs with lower and different skill requirements. We emphasize that measuring both formal degrees and occupational skills and their mismatch allows for a deeper understanding of overqualification and wage-setting.

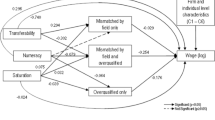

Source: Authors’ own graph, based on Reichelt and Vicari (2014)

Source: Own computations based on the NEPS-ADIAB

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For instance, an employee can be perfectly matched to his/her job regarding acquired and required formal qualification levels but has in fact fewer or different skills than the job requires.

Alternative approaches to measure the skill distance or the “skill transferability” between a pair of occupations were introduced by Backes-Gellner and Geel (2011) and Gathmann and Schönberg (2010). In both approaches, survey respondents were asked about the match of their trained skills and skills required in their current job. The individual reports were aggregated to information on an occupational level. These approaches have two main drawbacks. First, respondents tend to “stick” with their trained occupation, which means that they report a high congruency between trained skills and currently examined tasks even after an occupational change (Behringer 2002). Second, the survey data are not representative of less common occupations, as there are only few or no individual observations to be aggregated at the occupational level.

The author defines apparent overqualification as the case in which an individual is formally mismatched but satisfied with the match of his/her qualifications and work and genuine overqualification as the case in which an individual is formally mismatched and dissatisfied with the match between his/her qualifications and work (Chevalier 2003).

As stated in the introduction, overqualification and skills mismatch are capturing two different types of mismatch. In the same manner, this is true for the measurement of the mismatch of occupational skills. An employee can be well matched regarding formal qualification levels but mismatched with regard to acquired and required occupation-specific skills.

Wage setting depends not only on the qualification level but also on industrial sectors or unionization of an occupation or demand-side factors. For example, some unskilled assembly-line workers in the automobile industry earn far more than hairdressers (who receive vocational training) on average. This could be motivation for switching occupations and voluntarily working overqualified positions.

The first wave, which includes the survey period from 2009 to 2010, is linked to the administrative dataset.

Vocational training in Germany involves a 3–3.5 years’ apprenticeship program that usually starts after 9 years of schooling. It can also start after graduation from high school, which is after 13 years of schooling. In a few cases, there are also 2-year programs.

After implementation of the bachelor’s and master’s system in Germany (Bologna Process), the usual graduation time shifted to 3 years for completing bachelor’s studies and an additional 2 years for completing master’s studies. Before the reform, usual diploma or magister studies took 4–5 years until graduation. Only high school graduates, after 13 years of schooling, are eligible to attend university.

See the Robustness checks section for the results of other kinds of operationalisations.

For more information, please visit the BERUFENET homepage: http://berufenet.arbeitsagentur.de.

There are between 2 and 20 core requirements or 7.4 core requirements on average (Dengler et al. 2016) that describe each occupation. However, there is no evidence of a systematic difference in the description among different occupation types, such as occupations in the producing industry compared with occupations in the service sector.

Information on the current occupation and training occupation is reported by respondents in clear text fields. Later, it is coded by specially trained coders in a double coding process to increase the reliability of the codes. Information on the educational level and training is obtained via multiple-choice questions and is revised in a later module of the questionnaire to increase reliability.

Measured as occupational groups (a 3-digit code) of the German Classification of Occupations 2010 (KldB 2010).

All results are available upon request.

References

Abraham, M., & Schönholzer, T. (2009). Pendeln oder Umziehen? Entscheidungen über unterschiedliche Mobilitätsformen in Paarhaushalten. In P. Kriwy & C. Gross (Eds.), Klein aber fein! Quantitative empirische Sozialforschung mit kleinen Fallzahlen (pp. 247–268). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. H. (2011). Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. In C. David & A. Orley (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics—chapter 12 (Vol. 4, pp. 1043–1171)., Part B Elsevier: Amsterdam.

Allen, J., Levels, M., & van der Velden, R. (2013). Skill mismatch and skill use in developed countries: Evidence from the PIAAC Study. GSBE research memoranda, 13/061, Maastricht.

Allen, J., & van der Velden, R. (2001). Educational mismatches versus skill mismatches: Effects on wages, job satisfaction, and on-the-job search. Oxford Economic Papers, 53(3), 434–452.

Allmendinger, J. (1989). Educational systems and labor market outcomes. European Sociological Review, 5(3), 231–250.

Autor, D. H., & Handel, M. J. (2013). Putting tasks to the test: Human capital, job tasks, and wages. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(Special issue 1), 59–96.

Backes-Gellner, U., & Geel, R. (2011). Occupational mobility within and between skill clusters: An empirical analysis based on the skill-weights approach. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 3(1), 21–38.

Bauer, T. K. (2002). Educational mismatch and wages: A panel analysis. Economics of Education Review, 21(3), 221–229.

Becker, G. S. (1962). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5, Part 2), 9–49.

Behringer, F. (2002). Berufswechsel und Qualifikationsverwertung. Paper presented at the Berufsbildung für eine globale Gesellschaft Perspektiven im 21. Jahrhundert, Bonn,

Bielby, D. D. (1992). Commitment to work and family. Annual Review of Sociology, 18(1), 281–302.

Bijlsma, I., & van der Velden, R. (2015) Skill, skill use and wages: A new theoretical perspective. In PIAAC Conference, Haarlem, 22–24 November 2015.

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Mayer, K. U. (1988). Labor market segmentation in the Federal Republic of Germany: An empirical study of segmentation theories from a life course perspective. European Sociological Review, 4(2), 123–140.

Blossfeld, H. -P., Roßbach, H. -G., & von Maurice, J. (2011). Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 14(Special issue), 19–34.

Boll, C., & Leppin, J. S. (2013). Equal matches are only half the story: Why German female graduates earn 27% less than males. HWWI Research Paper, 138, 1–24.

Brynin, M. (2002). Overqualification in employment. Work, Employment & Society, 16(4), 637–654.

Brynin, M., & Longhi, S. (2009). Overqualification: Major or minor mismatch? Economics of Education Review, 28(1), 114–121.

Büchel, F. (1998). Zuviel gelernt? Ausbildungsinadäquate Erwerbstätigkeit in Deutschland. Berlin: Bertelsmann.

Büchel, F. (2001). Overqualification: Reasons, measurement issues and typological affinity to unemployment. In P. Descy & M. Tessaring (Eds.), Training in Europe: Second report on vocational training research in Europe 2000: Background report (pp. 453–560). Luxemburg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Budría, S. (2011). Are educational mismatches responsible for the ‘inequality increasing effect’ of education? Social Indicators Research, 102(3), 409–437.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2010). Microeconometrics using stata (2nd ed.). College Station: Stata Press.

Chevalier, A. (2003). Measuring over-education. Economica, 70(279), 509–531.

Chevalier, A., & Lindley, J. (2009). Overeducation and the skills of UK graduates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 172(2), 307–337.

Clark, D., & Fahr, R. (2001). The promise of workplace training for non-college-bound youth: Theory and evidence from German apprenticeship. IZA-Discussion Papers, 378, Bonn.

Dengler, K., Matthes, B., & Paulus, W. (2014). Occupational Tasks in the German Labour Market: An Alternative Measurement on the Basis of an Expert Database. FDZ-Methodenbericht, 12, Nürnberg.

Dengler, K., Stops, M., & Vicari, B. (2016). Occupation-specific matching efficiency. IAB-Discussion Paper, 16, Nürnberg.

Desjardins, R., & Rubenson, K. (2011). An analysis of skill mismatch using direct measures of skills. OECD Education Working Papers, 63, Paris.

DiPrete, T., De Graaf, P. M., Luijkx, R., Tahlin, M., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (1997). Collectivist versus individualist mobility regimes? Structural change and job mobility in four countries. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 318–358.

Flisi, S., Goglio, V., Meroni, E. C., Rodrigues, M., & Vera-Toscano, E. (2017). Measuring occupational mismatch: Overeducation and overskill in Europe—Evidence from PIAAC. Social Indicators Research, 131(3), 1211–1249.

Gathmann, C., & Schönberg, U. (2010). How general is human capital? A task-based approach. Journal of Labor Economics, 28(1), 1–49.

Green, F., & McIntosh, S. (2007). Is there a genuine under-utilization of skills amongst the over-qualified? Applied Economics, 39(4), 427–439.

Green, F., & Zhu, Y. (2010). Overqualification, job dissatisfaction, and increasing dispersion in the returns to graduate education. Oxford Economic Papers, 62(4), 740–763.

Hall, A. (2011). Gleiche Chancen für Frauen und Männer mit Berufsausbildung? Berufswechsel, unterwertige Erwerbstätigkeit und Niedriglohn in Deutschland. Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann Verlag.

Hartog, J. (2000). Over-education and earnings: Where are we, where should we go? Economics of Education Review, 19(2), 131–147.

Hartog, J., & Oosterbeek, H. (1988). Education, allocation ond eornings in the Netherlands: Overschooling? Economics of Education Review, 7(2), 185–194.

Hartog, J., & Sattinger, M. (2013). Nash bargaining and the wage consequences of educational mismatches. Labour Economics, 23, 50–56.

Haupt, A. (2016). Erhöhen berufliche Lizenzen Verdienste und die Verdienstungleichheit? Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 45(1), 39–56.

Kambourov, G., & Manovskii, I. (2008). Rising occupational and industry mobility in the United States: 1968–97. International Economic Review, 49(1), 41–79.

Kambourov, G., & Manovskii, I. (2009). Occupational specificity of human capital. International Economic Review, 50(1), 63–115.

Leuven, E., & Oosterbeek, H. (2011). Overeducation and mismatch in the labor market. Handbook of the Economics of Education, 4, 283–326.

Levels, M., Van der Velden, R., & Allen, J. (2014). Educational mismatches and skills: New empirical tests of old hypotheses. Oxford Economic Papers, 66(4), 959–982.

Matthes, B., & Vicari, B. (2017). Occupational Similarity. FDZ-Methodenreport, X, Nürnberg.

Mavromaras, K., McGuinness, S., & Wooden, M. (2007). Overskilling in the Australian labour market. Australian Economic Review, 40(3), 307–312.

McGowan, M. A., & Andrews, D. (2015). Labour market mismatch and labour productivity: Evidence from PIAAC data. OECD Economic Department Working Papers, 1209, Paris.

McGuinness, S. (2006). Overeducation in the labour market. Journal of economic surveys, 20(3), 387–418.

McGuinness, S., & Sloane, P. J. (2011). Labour market mismatch among UK graduates: An analysis using REFLEX data. Economics of Education Review, 30(1), 130–145.

Mincer, J. A. (1974). Age and experience profiles of earnings. In J. A. Mincer (Ed.), Schooling, experience, and earnings (pp. 64–82, Human Behavior & Social Institutions, Vol. 2). New York: NBER.

Müller, W., & Gangl, M. (2003). Transitions from education to work in Europe: The integration of youth into EU labour markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Müller, W., & Shavit, Y. (1998). The institutional embeddedness of the stratification process: A comparative study of qualifications and occupations in thirteen countries. In W. Müller & Y. Shavit (Eds.), From school to work (pp. 1–48). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Müller, W., Steinmann, S., & Ell, R. (1998). Education and labour-market entry in Germany. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work (pp. 143–188). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nawakitphaitoon, K., & Ormiston, R. (2016). The estimation methods of occupational skills transferability. Journal for Labour Market Research, 49(4), 317–327.

OECD. (2016). Skills matter: Further results from the survey of adult skills (OECD Skills Studies). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Paulus, W., & Matthes, B. (2013). The German Classification of Occupations 2010. Structure, Coding and Conversion Table. FDZ-Methodenreport, 8, Nürnberg.

Pellizzari, M., & Fichen, A. (2013). A new measure of skills mismatch: Theory and evidence from the survey of adult skills (PIAAC). OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Working Papers, 153, Paris.

Poletaev, M., & Robinson, C. (2008). Human capital specificity: Evidence from the Dictionary of Occupational Titles and Displaced Worker Surveys, 1984–2000. Journal of Labor Economics, 26(3), 387–420.

Quintini, G. (2011). Right for the job: Over-qualified or under-skilled? (Vol. 120). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Reichelt, M. (2015). Using longitudinal wage information in linked data sets. The example of ALWA-ADIAB. FDZ-Methodenreport, 1, Nürnberg.

Reichelt, M., & Abraham, M. (2017). Occupational and regional mobility as substitutes: A new approach to understanding job changes and wage inequality. Social Forces, 95(4), 1399–1426.

Reichelt, M., & Vicari, B. (2014). Ausbildungsinadäquate Beschäftigung in Deutschland: Im Osten sind vor allem Ältere für ihre Tätigkeit formal überqualifiziert. IAB-Kurzbericht, 25, Nürnberg.

Rohrbach-Schmidt, D., & Tiemann, M. (2016). Educational (Mis)match and skill utilization in Germany: Assessing the role of worker and job characteristics. Journal for Labour Market Research, 49(2), 99–119.

Sattinger, M. (1993). Assignment models of the distribution of earnings. Journal of Economic Literature, 31(2), 831–880.

Shaw, K. L. (1984). A formulation of the earnings function using the concept of occupational investment. Journal of Human Resources, 19(3), 319–340.

Shaw, K. L. (1987). The quit propensity of married men. Journal of Labor Economics, 5(4, Part 1), 533–560.

Szydlik, M. (1996). Zur Übereinstimmung von Ausbildung und Arbeitsplatzanforderungen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Mitteilungen aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, 29(2), 295–306.

Thurow, L. C. (1975). Generating inequality: Mechanisms of distribution in the US economy. New York: Basic Books.

Van der Velden, R., & Van Smoorenburg, M. S. M. (1997). The measurement of overeducation and undereducation: Self-report vs. job-analyst method. Maastricht Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market, Maastricht University.

Verhaest, D., & Omey, E. (2006). The impact of overeducation and its measurement. Social Indicators Research, 77(3), 419–448.

Verhaest, D., & Omey, E. (2010). The determinants of overeducation: Different measures, different outcomes? International Journal of Manpower, 31(6), 608–625.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Silke Anger, Britta Matthes, Joe King, Martin Abraham, Monika Jungbauer-Gans, the participants of the AG Qualität der Beschäftigung, IAB Nuremberg, the editor, and three anonymous reviewers for valuable comments and help. This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This paper uses data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS): Starting Cohort 6—Adults, doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC6:3.0.1. From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data were collected as part of the Framework Programme for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). As of 2014, the NEPS survey is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg in cooperation with a nationwide network.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kracke, N., Reichelt, M. & Vicari, B. Wage Losses Due to Overqualification: The Role of Formal Degrees and Occupational Skills. Soc Indic Res 139, 1085–1108 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1744-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1744-8