Abstract

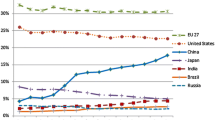

China has a long and proud history of world leadership in science and technology, but in the past two centuries it has experienced a period of instability that has challenged that leadership. However, since its political consolidation in the middle part of the 20th Century and its subsequent economic reforms, China’s rise in science has been meteoric. This rise was first detected by the scientometric community through its indicators, but it has now become obvious. Indeed in 2017 the question, “Will China come to lead world science?” was becoming to some, “Does China already lead world science?” This paper tries to make the case that the answer is “yes” (or at least “soon”)—but the answer depends on which metrics one considers. China already leads many countries in some measures of GDP, scientific paper production, researchers, plus high technology manufacturing and exports. China also recently passed the European Union in R&D investment. Even in some of those indicators where China has not yet taken the lead, reasonable forecasts predict that it soon will. However, there are some indicators where China is still far behind. For example while rising, it still lags the U.S. and EU in citations in Western publications, and will take years to catch up. Here, these quantitative measures are supplemented by qualitative ones from WTEC assessments and by survey results of scientists and the public, which present a more nuanced conclusion. While Chinese leadership may be difficult for Westerners to accept, it can be viewed as China merely regaining its historical position of leadership in science and technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Altmetric. (2017). Retrieved on March 8, 2017 from www.altmetric.com/top100/#country=China.

Aviation Week. (2013). Person of the year: Qian Zuesen. Retrieved on January 10, 2018 from http://aviationweek.com/blog/person-year-qian-xuesen.

Basu, A. (2006). Using ISI’s ‘Highly Cited Researchers’ to obtain a country level indicator of citation excellence. Scientometrics, 68(3), 361–375.

Basu, A., Foland, P., Holdridge, G., & Shelton R. D. (2017). China as number 1: The case for China regaining world leadership of science and technology. In Proceedings of ISSI 2017—the 16th international conference on scientometrics and informetrics (pp. 166–177). Wuhan, China: Wuhan University.

Basu, A., & Ghosh, S. (2017). Number of highly cited researchers in a country or field as an indicator of country performance in science, in preparation, 2017.

Côté, G., Roberge, G., & Archambault, E. (2016). Bibliometrics and patent indicators for the science and engineering indicators 2016—technical documentation. Montreal: Science metrix. Also see technical documentation annex. Retrieved on February 7, 2017 from http://www.science-metrix.com/sites/default/files/science-metrix/publications/science-metrix_sei_2016_technical_documentation_0.pdf.

Fairclough, R., & Thelwall, M. (2015). National research impact indicators from Mendeley readers. Journal of Informetrics, 9, 845–859.

Foland, P., Fadel, T., & Shelton, R. D. (2015). Causal connections between scientometrics indicators: Which ones best explain high-technology manufacturing outputs? In Proceedings of the 15th international conference on scientometrics and informetrics (pp. 662–672). Istanbul.

Frietsch, R., Helmich, P., & Neuhäusler, P. (2017). Performance and structures of the German Science System 2016. Berlin: Expertenkommission Forschung und Innovation. No. 5-2017. Prepared by the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research (ISI).

Funk, C., & Rainie, L. (2015). Public and scientists views on Science and Society. Pew Research Center. Retrieved March 14, 2017 from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/29/public-and-scientists-views-on-science-and-society/.

Hollingsworth, J. R., Müller, K. H., & Hollingsworth, E. J. (2008). The end of the science superpowers. Nature, 454(24), 411–412.

Javitz, H., Grimes, T., Hill, D., Rapoport, A., Bell, R., Fecso, R., Lehming, R. (2010). U.S. Academic scientific publishing. Working paper SRS 11-201. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics.

Jin, B., & Rousseau, R. (2005). China’s quantitative expansion phase: Exponential growth, but low impact. In P. Ingwersen & B. Larsen (Eds.), Proceedings of ISSI 2005 (pp. 362–370). Stockholm: Karolinska University Press.

McLaughlin, K. (2016). Science is a major plank in China’s new spending plan. Science. Retrieved December 2, 2017 from http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/03/science-major-plank-china-s-new-spending-plan.

Mirowski, P. (2011). Science-mart: Privatizing American science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Moed, H. F. (2002). Measuring China’s research performance using the Science Citation Index. Scientometrics, 53, 281–296.

Morring, F. (2016). How China is launching its big move into the orbital economy. Aviation Week and Space Technology. Retrieved January 10, 2018 from aviationweek.com/new-space/how-china-launching-its-big-move-orbital-economy.

Nanopolis. (2018). Retrieved January 10, 2018 from http://www.nanopolis.cn/en/Index.aspx.

Nelson, R. R. (1990). U.S. technological leadership: Where did it come from and where did it go? Research Policy, 19, 117–131.

NSB. (2016). Science and engineering indicators 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2017 from https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2016/nsb20161/#/.

NSB. (2018). Science and engineering indicators 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2018 from https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2018/nsb20181/report.

OECD. (2017). Main science and technology indicators. Retrieved February 1, 2017 from stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode = MSTI_PUB.

Perrett, B. (2014). Avic Hongdu delivers first major assembly for C919. Retrieved January 10, 2018 from http://aviationweek.com/awin-only/avic-hongdu-delivers-first-major-assembly-c919.

PISA. (2017). Program for international student assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2017 from http://www.businessinsider.com/pisa-worldwide-ranking-of-math-science-reading-skills-2016-12.

Shelton, R. D. (2008). Relations between national research investment and publication output: Application to an American paradox. Scientometrics, 74(2), 191–205.

Shelton, R. D., & Foland, P. (2009). The race for world leadership of science and technology: Status and forecasts. In Proceedings of the 12th international conference on scientometrics and informetrics (pp. 369–380). Rio. Also in Chinese in the 2010 volume of Science Focus, 5 (pp. 1–9).

Shelton, R. D., & Foland, P. (2017). Model-based forecasts of scientific indicators: China will soon lead the world in scientific papers. In Presented at Collnet 2017, July 11, 2017. Canterbury, England. Retrieved on January 1, 2018 from http://scienceus.org/s/Collnet2017.doc.

Shelton, R. D., & Holdridge, G. M. (2003). The US-EU race for leadership of science and technology: Qualitative and quantitative indicators. Scientometrics, 60(3), 353–363. Originally presented at the Ninth International Conference on Scientometrics and Informetrics, Beijing.

Tollefson, J. (2018). China declared world’s largest producer of scientific articles. Nature January 23, 2018. 553(7689), 390. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-00927-4. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

Top500. (2016). Press release. Retrieved April 14, 2017 from https://www.top500.org/news/new-chinese-supercomputer-named-worlds-fastest-system-on-latest-top500-list/.

UNESCO. (2017). Research funding data. Retrieved January 1, 2016 from data.uis.unesco.org/.

Wang, X., Fang, Z., Li, Q., & Guo, X. (2016). The poor Altmetric performance of publications authored by researchers in mainland China. arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.07424, 2016.

WIPO. (2017). IP Statistics Data Center. Retrieved April 2, 2017 from ipstats.wipo.int/ipstatv2/index.htm.

WTEC. (2018). Baltimore: World Technology Evaluation Center, Inc. Web site. Retrieved January 1, 2018 from wtec.org.

Zhou, P., & Leydesdorff, L. (2006). The emergence of China as a leading nation in science. Research Policy, 35(1), 83–104.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially sponsored by Grant ENG-0844639 from the National Science Foundation. The opinions herein are the authors’ and not necessarily the sponsor’s. The present study is an extended version of an article presented at the 16th International Conference on Scientometrics and Informatics, Wuhan (China), 16–20 October 2017 (Basu et al. 2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A. Basu: Formerly NISTADS, New Delhi (India).

G. Holdridge: Formerly worked for WTEC, when this paper was written.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Basu, A., Foland, P., Holdridge, G. et al. China’s rising leadership in science and technology: quantitative and qualitative indicators. Scientometrics 117, 249–269 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2877-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2877-5