Abstract

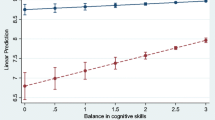

We compare skill sets of employees working in businesses of different size to the skill sets of entrepreneurs. Employees in large businesses tend to have a lower skill balance than those working in small businesses; yet, the skill balance of entrepreneurs remains the largest. Our evidence suggests that the skill level and skill scope matter for balance and increase with formal education levels but decrease with the number of previous occupations. We find a positive relationship between skill balance and income that is strongest for entrepreneurs. For employees, the relationship remains positive but the magnitude of the association decreases when business size increases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Skill balance can be observed on an individual and a firm level, which is why it is important to remember that here our focus is not on the entire business where skill balance can be achieved by groups of specialists who complement each other (e.g., Marino et al. 2012). Instead, the focus remains on the individual as in Lazear’s model of entrepreneurship.

Their measure is taken from a survey that assesses a total of five cognitive and social abilities. The abilities are (1) verbal, (2) mathematical, (3) technical, (4) clerical or coding speed, and (5) social ability (Hartog et al. 2010).

Intra-group variation, as found for employees, might also exist for the self-employed. The reported regressions already include controls for firm size. In separate regressions (available upon request), we investigate whether balance is higher for solo entrepreneurs who cannot yet rely on employees to compensate for their missing skills. There is no evidence of differences between self-employed persons with and without employees.

Tests for non-linearities in the relationship between prior occupations and skill balance (using higher-order polynomials or dummies for the number of prior occupations) confirm our findings of a negative association between the two variables.

Lazear’s theory expects individuals to increase the level of their weakest skill. Thus, we always take the highest skill level as the goal that needs to be achieved. If an individual reports both expert and basic skills we only count expert skills. We tried alternative balance measures that take into account both skill levels. It turns out that our alternative indices yield the same balance structure but display larger confidence intervals. Results are available upon request.

References

Armington, C., & Acs, Z. J. (2002). The determinants of regional variation in new firm formation. Regional Studies, 36(1), 33–45.

Åstebro, T., & Thompson, P. (2011). Entrepreneurs, Jacks of all trades or Hobos? Research Policy, 40(5), 637–649.

Audretsch, D. B., & Fritsch, M. (1994). The geography of firm births in Germany. Regional Studies, 28(4), 359–365.

Baron, R. A. (2003). Human resource management and entrepreneurship: Some reciprocal benefits of closer links. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 253.

Blau, P. M. (1970). A formal theory of differentiation in organizations. American Sociological Review, 35(2), 201–218.

Blau, P. M., & Schoenherr, R. A. (1971). The structure of organizations. New York: Basic Books.

Dobrev, S. D., & Barnett, W. P. (2005). Organizational roles and transition to entrepreneurship. The Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 433–449.

Elfenbein, D. W., Hamilton, B. H., & Zenger, T. R. (2010). The small firm effect and the entrepreneurial spawning of scientists and engineers. Management Science, 56(4), 659–681.

Hall, A., & Tiemann, M. (2006). BIBB/BAuA employment survey of the working population on qualification and working conditions in Germany 2006, suf_1.0. In Research Data Center at BIBB (Ed.), GESIS Cologne, Germany (data access). Bonn: Federal Institute of Vocational Education and Training. doi:10.4232/1.4820.

Hannan, M. T. (1988). Social change, organizational diversity, and individual careers. In M. A. Riley (Ed.), Social change and the life course. Newbury Park: Sage.

Hartog, J., van Praag, M., & van der Sluis, J. (2010). If you are so smart, why aren’t you an entrepreneur? Returns to cognitive and social ability: Entrepreneurs versus employees. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 19(4), 947–989.

Hyytinen, A., & Ilmakunnas, P. (2007). Entrepreneurial aspirations: Another form of job search? Small Business Economics, 29(1), 63–80.

Hyytinen, A., & Maliranta, M. (2008). When do employees leave their job for entrepreneurship? Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 110(1), 1–21.

Lazear, E. P. (2004). Balanced skills and entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 94(2), 208–211.

Lazear, E. P. (2005). Entrepreneurship. Journal of Labor Economics, 23(4), 649–680.

Lazear, E. P. (2012). Leadership: A personnel economics approach. Labour Economics, 19(1), 92–101.

Lazear, E. P. (2003). Entrepreneurship. IZA Discussion Paper No. 760. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Lee, S.-H. (2005). Generalists and specialists, abilities and earnings. Working Paper of Department of Economics, No. 05-02, University of Hawaii-Manoa.

Marino, M., Parotta, P., & Pozzoli, D. (2012). Does labor diversity promote entrepreneurship? Economic Letters, 116, 15–19.

Oberschachtsiek, D. (2012). The experience of the founder and self-employment duration: A comparative advantage approach. Small Business Economics, 39(1), 1–17.

Parker, S. C. (2009). Why do small firms produce the entrepreneurs? Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(3), 484–494.

Pugh, D. S., Hickson, D. J., Hinings, C. R., & Turner, C. (1969). The context of organizational structures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 14, 91–114.

Rohrbach-Schmidt, D. (2009). The BIBB/IAB- and BIBB-BAuA surveys of the working population on qualification and working conditions in Germany. In BIBB-FDZ Daten- und Methodenbericht 1/2009. Bonn: BIBB-FDZ.

Silva, O. (2007). The jack-of-all-trades entrepreneur: Innate talent or acquired skill? Economics Letters, 97(2), 118–123.

Sørensen, J. B. (2007). Bureaucracy and entrepreneurship: Workplace effects on entrepreneurial entry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(3), 387–412.

Stuetzer, M., Obschonka, M., & Schmitt-Rodermund, E. (2012). Balanced skills among nascent entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, forthcoming.

Wagner, J. (2003). Testing Lazear’s jack-of-all-trades view of entrepreneurship with German micro data. Applied Economics Letters, 10(11), 687–689.

Wagner, J. (2004). Are young and small firms hothouses for nascent entrepreneurs? Evidence from German micro data. Applied Economics Quarterly, 50(4), 379–391.

Wagner, J. (2006). Are nascent entrepreneurs ‘Jacks-of-all-trades’? A test of Lazear’s theory of entrepreneurship with German data. Applied Economics, 38(20), 2415–2419.

Williamson, O. E. (2002). The theory of the firm as governance structure: From choice to contract. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), 171–195.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Michael Fritsch, Ljubica Nedelkoska, Michael Wyrwich, and two anonymous referees for providing us with helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bublitz, E., Noseleit, F. The skill balancing act: when does broad expertise pay off?. Small Bus Econ 42, 17–32 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9474-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9474-z