Abstract

As state-level merit-based financial aid programs proliferate, analysts both find that these programs have a disproportionate effect on students traditionally under-represented in postsecondary education and question the use of limited public resources in an inefficient and inequitable manner. This study, using survey data regarding the perceptions of all potentially eligible scholarship recipients, explores the impact the Tennessee Education Lottery Scholarship on college access for minority and low-income students. The empirical results indicate that African American and low-income students are more likely to perceive their eligibility for merit-based scholarships as having an impact on their decision on whether or not to attend college. A consequential policy implication is that a liberally awarded merit-based scholarship program, while inefficient, may provide sustainable access for those students in greatest need of financial aid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Since the publication of these reports, the Civil Rights Project has moved to University of California, Los Angeles.

With regard to survey mechanics, high school principals from sampled schools received a letter requesting participation signed by the Executive Director of the Tennessee Higher Education Commission and the State Commissioner of Education. This official letter served to legitimate and convey the importance of survey completion with the ultimate hope that high schools would agree to participate. It is unlikely, however, to have engendered a particular substantive student response bias with regard to the questions analyzed in this study. In part, this is due to the frequency in which Tennessee high school students are surveyed. Moreover, a student response bias is unlikely because there was no link to the Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation, the state agency most recognized by students as making financial aid decisions.

As discussed earlier, the data were obtained through a stratified, rather than simple, random sample. The standard errors obtained from an estimation method that ignore a complex sampling design would be biased downward thereby making it much easier to obtain statistically significant findings.

In its first year, the Tennessee Lottery experienced sales that topped the billion dollar mark. By statute, approximately 25% of state lottery sales (or $250 million for academic year 2004–2005) was appropriated for merit aid scholarships.

Since the initial adoption of the lottery scholarship program, the State of Tennessee has enacted two major changes. First, in 2004, the state raised the eligibility criteria for the standardized test component from a 19 ACT score to a 21 ACT score. While raising the standardized test component of the scholarship eligibility requirement could be a tremendous setback for a program that is potentially situated to serve as an exemplar for providing wide access in a politically palatable manner, the 21 ACT score remains liberal relative to other state programs. Second, in 2005, the state increased the award amounts of the base scholarships by 10% and increased the need-based supplemental award by 50%. Eligible students with income levels below $36,000 will now receive scholarships up to $4,800 per year, which exceeds the cost of tuition at all Tennessee public universities. This suggests that Tennessee is committed to its original aim to increase college access.

References

Adelman, C. (1999). Answers in the tool box: Academic intensity, attendance patterns, and bachelor’s degree attainment. Washington, DC: Office of Educational Research and Improvement, U.S. Department of Education.

Adelman, C. (2002). The relationship between urbanicity and educational outcomes. In W. G. Tierney & L. S. Hagedorn (Eds.), Increasing access to college: Extending possibilities for all students (pp. 35–63). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance. (2001). Access denied: Restoring the nation’s commitment to equal educational opportunity. Washington, D.C.: Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance.

Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance. (2002). Empty promises: The myth of college access in America. Washington, D.C.: Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance.

Babbie, E. (1990). The practice of social research. (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Beattle, I. R. (2002). Are all “adolescent econometricians” created equal? Racial, class, and gender differences in college enrollment. Sociology of Education, 75(1), 19–43.

Becker, W. E. (2004). Omitted variables and sample selection problems in studies of college-going decisions. In E. P. St. John (Ed.), Readings on equal education (Vol. 19). Public policy and college access: Investigating the federal and state roles in equalizing postsecondary opportunity (pp. 65–86). New York: AMS Press, Inc.

Binder, M., & Ganderton, P. T. (2002). Incentive effects of New Mexico’s merit-based state scholarship program. In D. E. Heller & P. Marin (Eds.), Who should we help? The negative social consequences of merit scholarships (pp. 41–56). Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Binder, M., & Ganderton, P. T. (2004). The New Mexico lottery scholarship: Does it help minority and low-income students? In D. E. Heller & P. Marin (Eds.), State merit scholarship program and racial inequality (pp. 101–122). Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Cornwell, C., & Mustard, D. B. (2002). Race and the effects of Georgia’s HOPE scholarship. In D. E. Heller & P. Marin (Eds.), Who Should we help? The negative social consequences of merit scholarships (pp. 57–72). Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

DesJardins, S. L. (2001). Assessing the effects of changing institutional aid policy. Research in Higher Education, 42(6), 653–678.

Dynarski, S. (2000). Hope for whom? Financial aid for the middle class and its impact on college attendance. National Tax Journal, 53(3), 629–661.

Dynarski, S. (2002). Race, income, and the impact of merit aid. In D. E. Heller & P. Marin (Eds.), Who should we help? The negative social consequences of merit scholarships (pp. 73–92). Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Dynarski, S. (2004). The new merit aid. In C. M. Hoxby (Ed.), College choices: The economics of where to go, when to go, and how to pay for it (pp. 63–100). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Farrell, P. L. (2004). Who are the students receiving merit scholarships? In D. E. Heller & P. Marin (Eds.), State merit scholarship program and racial inequality (pp. 47–76). Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Freeman, K. (1997). Increasing African American participation in higher education: African American high-school students’ perspectives. Journal of Higher Education, 68(5), 523–550.

Fowler, F. J. (1995). Improving Survey Questions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Goggin, W. J. (1999). A “merit-aware” model for college admissions and affirmative action. Postsecondary Education Opportunity Newsletter (pp. 6–12). Mortenson Research Seminar on Public Policy Analysis of Opportunity for Postsecondary Education.

Hearn, J. C., Griswold, C. P., & Marine, G. (1996). Region, resources, and reason: A contextual analysis of state tuition and student aid policies. Research in Higher Education, 37(1), 241–278.

Heller, D. E. (1997). Student price response in higher education: An update to Leslie and Brinkman. Journal of Higher Education, 68(6), 624–659.

Heller, D. E. (1999). The effects of tuition and state financial aid on public college enrollment. Review of Higher Education, 23(1), 65–89.

Heller D. E. (Ed.). (2001). The states and public higher education policy: Affordability, access, and accountability. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Heller D. E. (Ed.) (2002a). Condition of access: Higher education for lower income students. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers (American Council on Education/Praeger Series on Higher Education).

Heller, D. E. (2002b). The policy shift in state financial aid programs. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: handbook of theory and research (Vol. XVII, pp. 221–261). New York: Agathon Press.

Heller, D. E. (2004a). The devil is in the details: An analysis of eligibility criteria for merit scholarships in Massachusetts. In D. E. Heller & P. Marin (Eds.), State merit scholarship program and racial inequality (pp. 23–46). Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Heller, D. E. (2004b). State merit scholarship programs: An overview. In D. E. Heller & P. Marin (Eds.), State merit scholarship program and racial inequality (pp. 13–22). Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Heller, D. E. (2006). MCAS scores and the Adams scholarships: A policy failure. Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Heller D. E., & Marin P. (Eds.). (2002). Who should we help? The negative social consequences of merit scholarships. Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Heller D. E., & Marin P. (Eds.). (2004). State merit scholarship program and racial inequality. Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Heller, D. E., & Rasmussen, C. J. (2002). Merit scholarships and college access: Evidence from Florida and Michigan. In D. E. Heller & P. Marin (Eds.), Who should we help? The negative social consequences of merit scholarships (pp. 25–40). Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

Heller, D. E., & Rogers, K. R. (2006). Shifting the burden: Public and private financing of higher education in the United States and implications for Europe. Tertiary Education and Management, 12(2), 91–117.

Hossler, D., Braxton, J., & Coopersmith, G. (1989). Understanding student college choice. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. V, pp. 231–288). New York: Agathon Press.

Hossler, D., Schmit, J., & Vesper, N. (1999). Going to college: How social, economic, and educational factors influence the decisions students make. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hu, S., & Hossler, D. (2000). Willingness to pay and preference for private institutions. Research in Higher Education, 41(6), 685–701.

Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP). (2002). Accounting for state student aid: How state policy and student aid connect. Washington, DC: IHEP.

Kipp, S. M., Price, D. V., & Wohlford, J. K. (2002). Unequal opportunity: Disparities in college access among the 50 states. Indianapolis, IN: Lumina Foundation for Education.

Lee, E. S., Forthofer, R. N., & Lortimor, R. J. (1989). Analyzing complex survey data. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Lehtonen, R., & Pahkinen, E. J. (2004). Practical methods for design and analysis of complex surveys. (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Levy, P. S., & Lemeshow, S. (2003). Sampling of populations: Methods and applications (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Long, B. T. (2004). The role of perceptions and information in college access: An exploratory review of the literature and possible data sources. Boston, MA: The Education Resources Institute (TERI).

McDonough, P. M. (1997). Choosing colleges: How social class and schools structure opportunity. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Nardi, P. M. (2003). Doing survey research: A guide to quantitative methods. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs (NASSGAP). (2007). 37th Annual Survey Report 2002–03 Academic Year. Washington, DC: NASSGAP.

National Center on Public Policy, Higher Education (NCPPHE), (2006). Measuring up. San Jose, CA: NCPPHE.

NCPPHE. (2000). Measuring up. San Jose, CA: NCPPHE.

NCPPHE. (2002a). Losing ground: A national status report on the affordability of American higher education. San Jose, CA: NCPPHE.

NCPPHE. (2002b). Measuring up. San Jose, CA: NCPPHE.

NCPPHE. (2004). Measuring up. San Jose, CA: NCPPHE.

Ness, E. C. (2008). Merit aid and the politics of education. New York: Routledge.

Ness, E. C., & Noland, B. E. (2007). Targeted merit aid: Implications of the Tennessee education lottery scholarship program. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 37(1), 7–17.

Paulsen, M. B. (1998). Recent research on the economics of attending college: Returns on investment and responsiveness to price. Research in Higher Education, 39(4), 471–489.

Paulsen, M. B., & St. John, E. P. (2002). Social class and college costs: Examining the financial nexus between college choice and persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 73(3), 189–236.

Perna, L. W. (2000). Differences in the decision to attend college among African Americans, Hispanics, and Whites. Journal of Higher Education, 71(2), 117–141.

Perna, L. W. (2005). The key to college access: Rigorous academic preparation. In W. G. Tierney, Z. Corwin, & J. Colyar (Eds.), Preparing for college: Nine elements of effective outreach (pp. 113–134). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Perna, L. W., Steele, P., Woda, S., & Hibbert, T. (2005). State public policies and the racial/ethnic stratification of college access and choice in the state of Maryland. Review of Higher Education, 28(2), 245–272.

Perna, L. W., & Titus, M. A. (2004). Understanding differences in the choice of college attended: The role of state public policies. Review of Higher Education, 27(4), 507–525.

Perna, L. W., & Titus, M. A. (2005). The relationship between parental involvement as social capital and college enrollment: An examination of racial/ethnic group differences. Journal of Higher Education, 76(5), 485–518.

Salant, P., & Dillman, D. A. (1994). How to conduct your own survey. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Skocpol, T. (1991). Targeting within universalism: Politically viable policies to combat poverty in the United States. In C. Jencks & P. Peterson (Eds.) The urban underclass (pp. 411–436). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Stevenson, D. L., Schiller, K. S., & Schneider, B. (1994). Sequences of opportunities for learning. Sociology of Education, 67(3), 184–198.

St. John, E. P. (1991). What really influences minority attendance? Sequential analysis of the High School and Beyond sophomore cohort. Research in Higher Education, 32(2), 141–158.

St. John, E. P. (2003). Refinancing the college dream: Access, equal opportunity, and justice for taxpayers. Baltimore, MC: Johns Hopkins University Press.

St. John, E. P. (2004). The impact of financial aid guarantees on enrollment and persistence: Evidence from research on Indiana’s twenty-first century scholars and Washington state achievers programs. In D. E. Heller & P. Marin (Eds.), State merit scholarship program and racial inequality (pp. 123–140). Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

St. John, E. P., Chung, C., Musoba, G. D., Simmons, A. B., Wooden, O. S., & Mendez, J. P. (2004a). Expanding college access: The impact of state finance strategies. Indianapolis, IN: Lumina Foundation for Education.

St. John, E. P., & Hu, S. (2004, April). Washington state achievers program: How does it influence student postsecondary educational opportunities? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA.

St. John, E. P., Hu, S., Simmons, A., & Musoba, G. D. (2001). Aptitude vs. merit: What matters in persistence? Review of Higher Education, 24(2), 131–152.

St. John, E. P., Musoba, G. D., Simmons, A. B., Chung, C. G., Schmit, J., & Peng, C. J. (2004b). Meeting the access challenge: An examination of Indiana’s twenty-first century scholars program. Research in Higher Education, 45(8), 829–871.

St. John, E. P., & Paulson, M. B. (2001). The finance of higher education: Implications for theory, research, policy, and practice. In M. B. Paulson & J. B. Smart (Eds.), The finance of higher education: Theory, research, policy, and practice (pp. 545–568). New York: Agathon Press.

St. John, E. P., Paulsen, M. B., & Carter, D. F. (2005). Diversity, college costs, and postsecondary opportunity: An examination of the nexus between college choice and persistence for African Americans and Whites. Journal of Higher Education, 76(5), 485–518.

Washington Higher Education Coordinating Board (WHECB). (2003). 2003–04 tuition and fee rates: A national comparison. Tacoma, WA: WHECB.

Acknowledgement

We thank Laura Perna, Michael Paulson, Ken Redd, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Selected Explanatory Variables

Appendix: Selected Explanatory Variables

The explanatory variables constructed for this study are grounded in previous studies from the college access literature. The purpose of this appendix is both to cite these relevant studies informing our study and, when applicable, to report how our measurement approach or data limitations may affect our findings.

Socioeconomic Status I—Income

Hu and Hossler (2000) advocate the use of a three-layered set of dummies: $35,000 or less; $50,000 or beyond; and $35,000–$50,000 (reference category). Including what amounts to be one additional dummy indicator into our specification does not alter either our principal income-oriented or race-based substantive conclusions. Perna and Titus (2004), however, make a persuasive case to create some sort of continuous SES composite index, rather than a single (or separate) measure(s) of financial resources. We take particular note to their comments regarding the interpretation of family income and potential for missing data problems. Nevertheless, given the importance of the $36,000 threshold (which will enable some students to increase their scholarship awards by one-third), missing family income data is rare (approximately 5%). We further justify this approach since this study considers only Tennessee students, who demonstrate less disparity than there may be across the nation. Admittedly, Perna and Titus (2004), who are inspired by Adelman (2002), raise a reasonable issue of weighting family income by family size. We are, however, unable to do this with our data.

Socioeconomic Status II—Parents Education

St. John and Paulsen (2001) and Paulsen and St. John (2002) contribute to the inclusion and construction of this variable. Additionally, Hu and Hossler (2000) recommend an alternative framework comprised of a set of dummies: high school or below; post college and beyond; some college or college (reference group). Our principal empirical results remain virtually unchanged (from a substantive standpoint) if we adopt this coding scheme.

Socioeconomic Status IV—Financial Aid Awareness

According to Long (2004), lack of information about financial aid programs may have implications for college access. Thus, we create a dichotomous measure of student familiarity with financial aid opportunities other than the Tennessee Education Lottery Scholarship. Some of the types of financial aid listed in the questionnaire include: Pell grants, Federal loans (Stafford/Perkins), TSAA/state grants, institutional scholarships and grants, ROTC scholarships, and scholarships offered by local organizations (i.e., churches, Rotary Club, etc.).

Scholarship Eligibility I—Standardized Test Performance

Tennessee is by and large an ACT-oriented state. Approximately 85% of the high school graduating class of 2004 took the ACT with a very small proportion of students electing to take the SAT. Over the last 15 years, higher education researchers have consistently found a positive relationship between test score performance and investment in higher education (Hossler et al. 1989; St. John 1991; Perna 2000; Beattle 2002; Perna and Titus 2004). By attempting to fuse the merit aid and college access literatures, some of our variable operationalizations may appear a bit unorthodox. Given the outcome variable of interest (perceived effect of merit aid on whether to attend college), we believe that this dichotomous eligibility variable is the most appropriate measure. We should note, however, that our results remain virtually unchanged (in terms of direction of effects and statistical significance of coefficients) irrespective of a variety of operational choices (i.e., a fully “continuous” measure of ACT or some other categorical breakdown).

Academic Preparation II—Highest Level of Math Taken

Perna and Titus (2004) cite several scholarly works (Adelman 1999; Perna 2005; Stevenson et al. 1994) that suggest high school curriculum is an unreliable measure of college preparation. Instead, Perna and Titus (2004), following Adelman (1999), suggest a variable that reflects the highest level of coursework completed in certain subjects (particularly math) as a more viable alternative. As such, we created a set of dummy categories—took Algebra I and Geometry, took Algebra II, and took one advanced math—and compared them with a reference group of other or no math.

Academic Aspirations

Based on the work of DesJardins (2001) we consider the idea of highest expected educational level. This is expressed operationally as a series of dummy indicators: high school or vocational degree; Associate’s (2-year degree); Bachelor’s (4-year degree-reference group); master’s degree; and Ph.D. or professional degree (i.e., law, medicine). Hu and Hossler (2000) offer a simpler taxonomy by collapsing these into three categories: vocational-technical and 2-year college; master’s or professional degree; and, 4-year college (reference group). Our overall conclusions are robust to this design consideration. We should note, however, that given that the dependent variable in Columns 3 and 4 of Table 2 is defined, in part, by students’ educational plans, we restrict their inclusion to Column 1.

Academic Achievement—High School Rank and School Quality

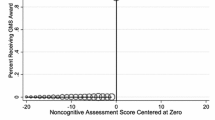

The merit-aware index recommended by Goggin (1999) serves as a proxy to high school rank and school quality included in St. John et al. (2001). This measure is produced by subtracting the school’s mean ACT score from the respondent’s. We should note that mean Tennessee high school ACT scores were purchased from ACT (http://www.act.org), in Iowa City, IA. The merit-aware index is constructed as follows: MAI = ACTstudent − ACTschool average.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ness, E.C., Tucker, R. Eligibility Effects on College Access: Under-represented Student Perceptions of Tennessee’s Merit Aid Program. Res High Educ 49, 569–588 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9096-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9096-5