Abstract

Whether highly educated women are exiting the labor force to care for their children has generated a great deal of media attention, even though academic studies find little evidence of opting out. This paper shows that female graduates of elite institutions have lower labor market involvement than their counterparts from less selective institutions. Although elite graduates are more likely to earn advanced degrees, marry at later ages, and have higher expected earnings, there is little difference in labor market activity by college selectivity among women without children and women who are not married. But the presence of children is associated with far lower labor market activity among married elite graduates. Most women eventually marry and have children, and the net effect is that labor market activity is on average lower among elite graduates than among those from less selective institutions. The largest gap in labor market activity between graduates of elite institutions and less selective institutions is among MBAs, with married mothers who are graduates of elite institutions 30 percentage points less likely to be employed full-time than graduates of less selective institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Many papers examine the opting out hypothesis by comparing women’s employment rates by cohort, education, presence of children, or occupation and generally find little evidence of a trend in labor force exit of more educated mothers (e.g., Boushey 2005, 2008; Goldin 2006; Percheski 2008; Antecol 2011; Hotchkiss et al. 2011). Shang and Weinberg (2013) do not examine the opting out hypothesis directly but find a trend of higher fertility among more educated women, which could be consistent with greater opting out of more educated women.

Notably, the highly publicized articles in the media assert that opting out is a trend, but do not provide any empirical support of a trend. Specifically, Belkin’s (2003) New York Times Magazine cover article, in which she coined the term “opt-out revolution,” profiles a group of female Princeton graduates and MBAs who left successful careers in order to care for their children, and Story (2005) profiles students at Yale.

Herr and Wolfram (2012) do not examine trends in opting out over time but compare employment rates by highest degree using data from the Harvard graduating classes of 1988–1991 who responded to the 10th and 15th anniversary reports. They report a response rate for women of 55 %.

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (1994).

Barron’s Educational Series, Inc. (1994).

Because there are no earlier data that would allow examination of trends, this paper does not provide direct evidence on whether the lower labor market activity of elite graduates relative to graduates of less selective institutions identified in this paper represents a change over time.

The effect of higher wages on hours worked conditional on the decision to work positive hours (that is, the intensive margin) is ambiguous as income and substitution effects have opposite effects on hours worked.

However, the effect of assortative marriages on labor supply may be small, as women’s labor supply has become less responsive to their husbands’ wages over the 1980–2000 period (Blau and Kahn 2007).

See U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (2005). For example, data from the Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Studies show that in 1992–1993, which is close to the average graduation year within the sample examined in this paper of 1989, the percent who borrowed for their undergraduate education by family income quintile is as follows: lowest, 66.7; lower middle, 45.1; upper middle, 34.3; highest, 24.3. See http://nces.ed.gov/das/library/tables_listings/2005170.asp.

See thttp://www.nsf.gov/statistics/sestat/ for information about the SESTAT surveys and for access to data and questionnaires. Except for the 1993 and 2003 surveys, the NSCG is limited to science and engineering degree holders or those in science and engineering occupations. The 1993 and 2003 NSCG surveys are special baseline surveys that include college graduates with degrees in any field.

The weighted response rate is 73 %, with the sampling weights designed to reflect differential selection probabilities on the basis of demographics, highest degree, occupation, and sex, and adjusted to compensate for nonresponse and undercoverage of smaller groups. See http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvygrads/.

Specifically, the highest degree for those with a professional degree in the field of law/prelaw/legal studies are categorized as JDs; those with a professional degree in the field of medicine (which includes dentistry, optometry, and osteopathy) are categorized as MDs; those with highest degree master’s in a business field such as accounting, business administration, financial management, and marketing are categorized as MBAs; those with highest degree master’s in an education field such as mathematics education, education administration, secondary teacher education, and so forth are categorized as MA education. All remaining degrees are grouped into other professional degrees, MA other, or highest degree bachelor’s.

Of the full sample of 100,402 observations, there are 76 respondents who report a non-US location. I group these with the omitted category in the regressions.

This NSCG measure that combines education and occupational information mitigates possible endogeneity of spouse’s earnings with own labor supply and also provides a measure reflecting permanent income or longer-term earnings. Any findings may be similar, however, if controlling instead for spouse’s earnings. Bertrand et al. (2010) report that in their analysis of labor supply of female MBAs their qualitative findings are similar when controlling either for spouse’s earnings category in the survey year or for spouse’s relative education level.

See College Board, Trends in College Pricing 2012, Figure 24A, available at http://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing.

Carnegie classification is not reported in the 1993 NSCG.

Data sets that report college information include the National Longitudinal Study of the High School Class of 1972 (NLS72), High School and Beyond (HS&B), National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), and the 1975 and 1976 waves of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). The sample of married mothers using the NLS72, HS&B, NLSY79 or PSID would be far smaller than available in the NSCG. Brewer et al. (1999) report a maximum of 3,062 observations with any college attendance (whether or not they graduated) in the NLS72 and a maximum of 2,165 similar observations in the 1982 HS&B cohort, and they note that their sample sizes are reduced dramatically if restricted to college graduates. Monks (2000) reports a sample of 1,087 college graduates in the NLSY79 that he was able to match to Barron’s categories. Arum et al. (2008) report a sample of 293 married female college graduates ages 25–55 in the 1975 wave of the PSID.

Some two-year colleges offer bachelor’s degrees in some majors or cooperatively with another four-year institution. I group the handful of respondents with bachelor’s degrees from associates of arts institutions with specialized institutions.

These are ‘free-standing campuses’ and include professional schools that offer most of their degrees in one area (e.g., medical centers, law schools, schools of art, music, and design, and theological seminaries). Among the specialized institutions are highly selective universities such as the United States Air Force Academy and the United States Naval Academy and institutions such as The Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, that are difficult to classify. See http://sestat.nsf.gov/docs/carnegie.html and Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (1994).

Barron’s categorizes professional schools of arts, music, and theater arts as ‘special.’ Barron’s ‘special’ schools are therefore a subset of institutions classified as ‘specialized’ in the Carnegie classification system.

Specifically, tests for differences in proportions are as follows: private Research I and private Research II compared to private Liberal Arts I yields z = 5.25 (e.g., comparing 32/40–54/159); private Research I and private Research II compared to public Research I yields z = 6.04; public Research I and private Liberal Arts I yields z = 2.20; public Research I to all categories except private Research I, private Research II, and private Liberal Arts I yields z = 8.16. Differences between other categories are not statistically significant. My grouping differs from that of Bertrand et al. (2010, footnote 2), who classify as ‘selective’ those institutions with Carnegie classifications of Research I and Liberal Arts I regardless of public or private status. Separating private and public colleges into different tiers is also supported by the findings of Brewer et al. (1999) on the relation between college status and earnings. Their study shows a large premium to attending an elite private college and a smaller premium to attending a middle-rated private college, with little support for a premium to higher-quality public institutions.

The pattern shown for part-time employment is similar if calculated conditional on employment.

The NSCG includes students on ‘paid work-study’ as working for pay or profit. I chose to include full-time students in the analyses that are not stratified by highest degree and to exclude full-time students in the analyses by highest degree. No results of this paper are affected by whether students are included or excluded from any of the analyses, in part because the sample design results in relatively few students in the sample and in part because the employment rate for students is similar to that of nonstudents, as many students are employed (not only in work-study jobs). For example, excluding full-time students from the calculations results in only two differences in the statistical significance of differences by tier relative to those reported in Panel A of Table 2: the difference in employment rates between tier 1 and tier 2 graduates becomes statistically significant at the 5 % level; and the difference in part-time employment between tier 1 and tier 4 graduates is no longer significant at the 5 % level. The reason for my choice of treatment of full-time students is as follows. First, because graduates of elite institutions are more likely to earn post-baccalaureate degrees, excluding students would raise the concern that the gap in labor market activity by college selectivity is driven by a combination of higher graduate school enrollment among elite bachelor’s degree graduates accompanied by lower labor market activity while a student. Second, although setting a minimum age for the sample at which it is expected that schooling is completed might mitigate the first concern, examination of the distribution of ages of full-time students as well as the distribution of ages at which the highest degree is attained shows that the age range of students and age at highest degree attainment is broad, and any choice of minimum age would be arbitrary. Third, however, I do exclude students from the analyses by highest degree attained in order to examine the relation between labor market activity and highest degree attained, while controlling for selectivity of highest degree in addition to selectivity of bachelor’s degree.

Descriptive statistics for the full sample and by tier for all variables defined in Section 3 and used in the regressions that follow are provided in “Appendix 1”.

MBAs are reported as master’s degrees and are not included with professional degrees.

With the exception of graduates of private Liberal Arts I colleges (tier 2), there is little difference within tiers by cohort with highest degree PhD, professional, or MBA. The share of tier 2 graduates with these degrees increases from 13 % among the age 23–35 cohort to 20 % in both of the older cohorts.

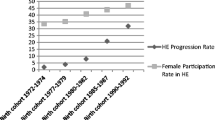

The ratio of men relative to women for different cohorts has been shown to influence female labor force participation (e.g., Grossbard and Amuedo-Dorantes 2007). In addition to the overall impact of sex ratios on labor force participation within cohorts, it is also possible that even within cohorts, sex ratio effects may vary by college selectivity. The descriptive statistics by cohort presented in Table 4 suggest that differential effects on the basis of college selectivity may arise: among married women with children ages 18 and younger, the smallest gap in labor force participation between tier 1 and tier 4 graduates is among the oldest cohort who were born in the post-WWII period in which the sex ratio was low, and the largest gap is among the youngest cohort who were born in a period in which the sex ratio was high.

Because the timing of marriage and having children differs by tier, when restricting the samples to married women with children ages 18 and younger, the composition of the tiers also differs by cohort. For example, within the youngest cohort, tier 1 graduates who are married with children may be those less attached to the labor force than are other tier 1 graduates who are statistically more likely to delay having children. The estimates by cohort are therefore comparing average labor market activity by tier among women who have displayed on average different preferences for timing of marriage and childbearing. The regressions control for extensive observable characteristics and any remaining unexplained disparity in labor market activity by tier within cohort may reflect heterogeneity in preferences for market work that differ by tier and cohort.

The results are similar if those who are missing Carnegie classification or are graduates of specialized institutions or non-US institutions are excluded from the regressions.

For example, for the estimates shown in “Appendix 2” which pool all women, there is one exception to the absence of significant differences among not-married women and married women without children: not-married women with children in tier 4 are significantly more likely to be labor force participants than not-married women with children in tiers 1–3. The estimates by cohort also show significantly higher labor force participation for not-married women with children.

If women who attend elite colleges are less likely to reside in proximity to their families, one mechanism for their lower labor market activity could be lesser availability of family childcare. Compton and Pollak (2011) find a positive effect on employment of proximity to family among married women with children. As a proxy for the likelihood of living in proximity to family, I use available information in the NSCG on region of high school attendance and current region to construct a variable indicating whether the regions are the same (where region in both cases is reported in 9 categories). I find that elite graduates are less likely to currently live in their high school region. Among those in the sample who are married with children ages 18 or younger, the percent living in their high school region is as follows: tier 1—50 %; tier 2—58 %; tier 3—68 %, and tier 4—73 %. In addition, labor market activity is greater for those who live in their high school region (although the relation is not always statistically significant). To the extent that living in the same region is a reliable indicator of proximity to family, this finding is consistent with Compton and Pollak (2011). Because the estimated coefficients are very similar with and without inclusion of the indicator for same region, as well as because the proxy for proximity to family is weak relative to that used by Compton and Pollak, the reported regressions exclude this variable.

Table 7 indicates those differences that are statistically significant at the 5 % level. Some disparities that are significant at the 10 % level (e.g., among those with JDs) are not discussed in this paper.

JDs are an exception, as differences by tier arise among those without children.

References

Antecol, H. (2011). The opt-out revolution: Recent trends in female labor supply. In S. W. Polachek & K. Tatsiramos (Eds.), Research in labor economics (Vol. 33, pp. 45–83). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing, Ltd.

Arum, R., Roksa, J., & Budig, M. (2008). The romance of college attendance: Higher education stratification and mate selection. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 26(2), 107–121.

Barron’s Educational Series. (1994). Barron’s profiles of American colleges: Descriptions of the colleges (20th ed.). New York: Barron’s Educational Series, Inc.

Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1986). Human capital and the rise and fall of families. Journal of Labor Economics 4(3, pt. 2), S1–S39.

Belkin, L. (October 26, 2003). The opt-out revolution. The New York Times Magazine.

Bertrand, M., Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2010). Dynamics of the gender gap for young professionals in the financial and corporate sectors. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(3), 228–255.

Black, D., Daniel, K., & Smith, J. (2005). College quality and wages in the United States. German Economic Review, 6(3), 415–443.

Blau, F., & Kahn, L. M. (2007). Changes in the labor supply behavior of married women: 1980–2000. Journal of Labor Economics, 25(3), 393–438.

Boushey, H. (2005). Are women opting out? Debunking the myth. Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) Briefing Paper.

Boushey, H. (2008). ‘Opting out?’ The effect of children on women’s employment in the United States. Feminist Economics, 14(1), 1–36.

Brand, J. E., & Xie, Y. (2010). Who benefits most from college? Evidence for negative selection in heterogeneous economic returns to higher education. American Sociological Review, 75(2), 273–302.

Brewer, D. J., Eide, E. R., & Ehrenberg, R. G. (1999). Does it pay to attend an elite private college? Journal of Human Resources, 34(1), 104–123.

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. (1994). A classification of institutions of higher education/with a foreword by Ernest L. Boyer, 1994 ed. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Charles, K. K., Hurst, E., & Killewald, A. (2013). Marital sorting and parental wealth. Demography, 50(1), 51–70.

College Board. (2012). Trends in college pricing. Available at http://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing.

Compton, J., & Pollak, R. A. (2011). Family proximity, childcare, and women’s labor force participation. NBER Working Paper 17678.

Dale, S. B., & Krueger, A. B. (2002). Estimating the payoff to attending a more selective college: An application of selection on observables and unobservables. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1491–1527.

Dale, S., & Krueger, A. B. (2011). Estimating the return to college selectivity over the career using administrative earnings data. NBER Working Paper 17159.

Fortin, N. M. (2009). Gender role attitudes and women’s labor market participation: Opting-out, AIDS, and the persistent appeal of housewifery. Unpublished paper.

Goldin, C. (2006). The quiet revolution that transformed women’s employment, education, and family. American Economic Review, 96(2), 1–21.

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2008). Transitions: career and family cycles of the educational elite. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 98(2), 363–369.

Grossbard, S., & Amuedo-Dorantes, C. (2007). Cohort-level sex ratio effects on women’s labor force participation. Review of Economics of the Household, 5(3), 249–278.

Grossbard-Shechtman, A. (1984). A theory of allocation of time in markets for labor and marriage. Economic Journal, 94(4), 863–882.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (1993). On the economics of marriage—a theory of marriage, labor and divorce. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hearn, J. C. (1984). The relative roles of academic, ascribed, and socioeconomic characteristics in college destinations. Sociology of Education, 57(1), 22–30.

Herr, J. L., & Wolfram, C. (2012). Work environment and “opt-out” rates at motherhood across high-education career paths. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 65(4), 928–950.

Hotchkiss, J. L., Pitts, M. M., & Walker, M. B. (2011). Labor force exit decisions of new mothers. Review of Economics of the Household, 9(3), 397–414.

Hoxby, C. M., & Avery, C. The missing ‘one-offs’: The hidden supply of high achieving, low income students. Forthcoming in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

Juhn, C., & Potter, S. (2006). Changes in labor force participation in the United States. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(3), 27–46.

Kreider, R. M., & Elliott, D. B. (2009). America’s families and living arrangements: 2007. Current Population Reports P20–561, U.S. Census Bureau.

Kurtulus, F. A., & Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (2012). Do female top managers help women to advance? A panel study using EEO-1 records. The Annals of American Academy of Political and Social Science, 639, 173–197.

Macunovich, D. J. (2010). Reversals in the patterns of women’s labor supply in the United States, 1977–2009. Monthly Labor Review, 133(11), 16–36.

Matsa, D. A., & Miller, A. R. (2011). Chipping away at the glass ceiling: Gender spillovers in corporate leadership. American Economic Review, 101(3), 635–639.

Monks, J. (2000). The returns to individual and college characteristics: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Economics of Education Review, 19(3), 279–289.

Percheski, C. (2008). Opting out? Cohort differences in professional women’s employment rates from 1960 to 2005. American Sociological Review, 73(3), 497–517.

Ramey, G., & Ramey, V. A. (2010). The rug rat race. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 129–176.

Schwartz, C. R., & Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42(4), 621–646.

Shang, Q., & Weinberg, B. A. (2013). Opting for families: Recent trends in the fertility of highly educated women. Journal of Population Economics, 26(1), 5–32.

Story, L. (September 20, 2005). Many women at elite colleges set career path to motherhood. The New York Times.

U.S. Dept. of Education (2005). Debt Burden: A comparison of 1992–1993 and 1999–2000 Bachelor’s degree recipients a year after graduating. National Center for Education Statistics, NCES 2005–170.

Williams, J. C., Manvell, J., & Bornstein, S. (2006). ‘Opt out’ or pushed out?: How the press covers work/family conflict—the untold story of why women leave the workforce. University of California, Hastings College of the Law: The Center for WorkLife Law.

Acknowledgments

I thank Alison Del Rossi, Shoshana Grossbard, Sharon Shewmake, Bruce Weinberg, and seminar participants at the University of Wyoming and Sewanee: The University of the South for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hersch, J. Opting out among women with elite education. Rev Econ Household 11, 469–506 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9199-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9199-4

Keywords

- Opting out

- Married women

- Female graduates

- Elite institutions

- Women graduates

- Mothers

- Labor market activity