Abstract

Historians often present their interpretation of the past in written accounts. In order to gain deeper knowledge of the discipline of history, students must learn how to read and write historical accounts. In this experimental pretest–posttest study, we investigated the impact of a domain-specific reading instruction followed by domain-specific writing-strategy instruction as well as a repeated domain-specific reading instruction on the quality of written texts and on procedural knowledge regarding reading, reasoning, and writing of 142 10th grade students. Results indicated that both instructions had a positive impact on the quality of written texts and on the amount of procedural knowledge (reading, reasoning, and writing). However, students who received a domain-specific writing instruction after the reading instruction wrote better texts compared to students who only received a domain-specific reading-to-write instruction. In addition, we found positive correlations between procedural knowledge and the quality of written texts in both conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In current history curricula, researchers focus more and more on fostering students’ reasoning using historical facts, concepts, and procedures. This approach assumes that understanding history is more than knowledge of historical events and that historians have their own approaches for interpreting the past and writing accounts (Chapman, 2011; Paul, 2019). In schools, students are often expected to interpret past events and to present their interpretation in an argumentative text (De La Paz, 2005; De La Paz & Felton, 2010; van Boxtel & van Drie, 2018; Wissinger et al., 2020). Primary sources (e.g., chronicles) play an important role when historians interpret the past. Historians embed these sources in their arguments to underpin their interpretation (Wineburg, 1991, 1998). The understanding of primary sources is often part of current discussions between historians. Consequently, current historiographical discussions and the reading of primary sources intertwine (Fallace & Neem, 2005).

History education researchers often focus on reading primary sources (e.g., letters) or on writings that use primary sources. This kind of research has developed useful insights (e.g., De La Paz, 2005; Reisman, 2012). Reading historical accounts, in which historians present an underpinned interpretation of the past, has gained less attention (Cercadillo et al., 2017; Innes, 2020). Reading accounts is important in order to understand how other historians interpreted the past, which is useful to develop a personal interpretation. Historical accounts can also inform students how historians’ perspectives have developed over time. Descriptions of the past are not fixed and can change due to developing frames of reference and new questions that arise. This flexible relationship between the present and the past becomes clearly visible in discussions about the significance of historical persons and events (Hunt, 2000; Lévesque, 2008; Seixas & Morton, 2012). For example, many statues of national heroes were built in the nineteenth century. Although these persons are still significant, current historians consider these monuments more critically, which has led to discussions as to whether these statues should be removed.

To improve students’ reasoning and written interpretation, researchers in history education often focus on the impact of domain-specific writing-strategy instruction. Instructional principles such as explicit instruction, prompts, small group work, and whole-class discussion have made a positive impact on the quality of written texts (e.g., De La Paz, 2005; De La Paz et al., 2022; van Drie et al., 2015; van Drie et al., 2021; Wissinger et al., 2020). These general principles are made domain-specific, by, for example, by focusing on historical evidence and using the historical context in order to comprehend evidence (Monte-Sano, 2010). Domain-specific writing instruction, teaches students how to construct historical arguments from multiple, sometimes conflicting, sources and use examples, details, or quotations to substantiate claims (Wissinger & De La Paz, 2016). Another approach focuses on reading instruction. In a meta-analysis, Graham et al. (2018) found positive effects of reading instruction on writing. Although not widely researched in history education, we found positive effects in an earlier study (van Driel et al., 2022). Because reading and writing are important for writing about historical significance, we are interested in the additional effect of writing instruction compared to reading instruction on the quality of written texts.

Reading accounts, arguing for a particular interpretation of the past, or judging the significance of a historical agent requires procedural knowledge, which is associated with the development of historical reasoning (e.g., Stoel et al, 2017), reading (e.g., van Gelderen et al., 2007), and writing (Klein & Kirkpatrick, 2010). However, our knowledge of how procedural knowledge contributes to reading, reasoning, and writing in history classrooms is limited. We need to know how students acquire procedural knowledge (Gross, 2002; van Drie et al., 2018).

In this experimental study, we aimed to compare the effects of a domain-specific reading-to-write instruction followed by a domain-specific writing-strategy instruction with a repeated domain-specific reading-to-write instruction. This study was conducted with 142 10th grade students who read historical accounts and developed a unique claim about the significance of historical agents in a written text. The reading and writing condition (R&W) received domain-specific reading-to-write instruction. This instruction was followed by domain-specific writing instruction. The reading-to-write condition (R&R) received two domain-specific reading-to-write instructions.

Theoretical framework

Reading historical accounts

People in the past have left traces such as diaries and paintings. Historians’ craft is to analyze these traces and to construct a coherent picture of the past—substantiated with evidence, arguments and comprehended within the historical context (Chapman, 2011; Paul, 2019; Wineburg, 1991, 1998). Historians commonly present their understanding of the past in accounts, which often contain arguments embedded in a narrative. This means that claims about the significance of historical agents need to be underpinned with arguments. The complete set of historical accounts is called historiography. Discussions regarding historiography may elicit other historical questions; consequently, history is an ongoing interpretation of the past (Paul, 2017). In the context of historical significance, this means that historians attempt to understand how the assignment of significance to the past has changed over time, how to relate different accounts to each other, and how to relate accounts to the broader historiographical discussion (Fallace, 2007; Fallace & Neem, 2005; Seixas & Morton, 2012).

Understanding historians’ discussions and how historians argue in their accounts seems difficult for students. A small-scale study found that history teachers considered evolving interpretations of the past as too complex for senior high school students (Wansink et al., 2018). Reading conflicting historical accounts has not garnered much attention by educational researchers (Cercadillo et al., 2017; Innes, 2020). However, reading historical accounts could deepen students’ understanding of the history discipline because doing so requires recognition and understanding of historians’ perspectives—how facts are made meaningful by historians and how they argue in order to place (counter)factual evidence in the background or foreground (Fallace & Neem, 2005; Körber, 2015; Schleppegrell & de Oliveira, 2006). Although historical reading aligns with close reading, close reading can be operationalized in different ways—analyzing how writers use language to reach a goal belongs to every model (Fang, 2016).

Comprehending the metatextual level of historical accounts is not often practiced in classrooms, but there is reason to believe that students could learn to understand history as an ongoing interpretation of the past. Previous research has shown that students of different age groups showed basic understanding of the existence of different perspectives in history (Cercadillo, 2001; Cercadillo et al., 2017; Houwen et al., 2020). In addition, because students are able to learn specific features of language after instruction (Levine, 2014), they could learn specific historical language in order to analyze how historians assign significance to the past. Furthermore, instruction about reading historical accounts more often provoked students’ knowledge of the interpretative nature of history, compared to students who did not receive that instruction (van Driel et al., 2022).

Writing in history education

In the last decades, a growing body of research has stressed the importance of domain-specific writing, which assumes that every discipline possesses its own approach to writing. An often-applied approach is strategy instruction (Klein & Boscolo, 2016).

According to Klein and Boscolo (2016), strategy instruction in history education often includes reading primary documents and developing (counter)arguments and rebuttals. Special attention must be paid to the construction of counterarguments because students seldom involve counterarguments in their argumentation (van Drie et al., 2006). There is reason to believe that strategy instruction improves text quality regarding historical argumentation and the interpretation of historical sources. In these studies, historians’ approaches are adapted to classrooms, which means that arguments are made more explicit than in narratives. Students are often expected to involve a claim and evidence, based on historical sources (comprehended with the historical context) or accurate interpreted facts in their arguments (e.g., Coffin, 2006; De La Paz, 2005; De La Paz & Felton, 2010; De La Paz et al., 2017; Monte-Sano, 2010; Schleppegrell, 2004; van Drie et al., 2015; Wissinger et al., 2020).

Despite the promising results of writing-strategy instruction, there is need for other approaches to gain more insight into the benefits and limitations of each approach (van Drie et al., 2015; Wissinger et al., 2020). Another approach is reading-to-write instruction, which assumes that reading and writing appeal to the same knowledge base, such as domain knowledge, text attributes, and procedural knowledge (Fitzgerald & Shanahan, 2000). Consequently, explicit reading instruction may also improve text quality. Although reading instruction does not always improve students’ writing (Goldman et al., 2019), a meta-analysis by Graham et al. (2018) shows that a small or moderate effect is typical. For instance, reading instruction about text structure, discussing content, identifying text statements, the use of specific language, and even independent reading might improve students’ ability to write a persuasive text or to summarize and interpret a text (Crowhurst, 1990; Jouhar & Rupley, 2021; Levine, 2014).

In the field of history education, our knowledge of the effects of reading-to-write instruction is limited. Former research has shown that reading instruction improves writing; however, the quality (e.g., Introduction and Conclusion) can always be improved (van Driel et al., 2022). For that reason, it seems important to investigate the effects of reading instruction and to compare the outcomes with a combined reading and writing instruction. Indeed, a combined instruction might be the most effective overall (Fitzgerald & Shanahan, 2000).

Procedural knowledge

During our review of previous research, we made (indirect) references to procedural knowledge, which is an abstract kind of knowledge. Procedural knowledge can illuminate the justification of knowledge in a particular domain (Hofer, 2004; Poitras & Lajoie, 2013). In our study, procedural knowledge informs researchers (1) of how to assign historical significance and (2) how to regard reading and writing in the context of a task about historical significance.

The concept of historical significance is a metahistorical concept, which could be used to organize factual knowledge and to construct a reasoning about historical phenomena (van Boxtel & van Drie, 2018). Judgements about the significance of a historical agent are based on criteria, which often focus on the consequences caused by this historical agent over time (e.g., Hunt, 2000; Lévesque, 2008). Although our knowledge about how students use these criteria is limited, knowledge of these criteria could be helpful while assigning significance to the past.

General research has revealed the importance of procedural knowledge for reading (e.g., Trapman et al., 2014; van Gelderen et al., 2007) and writing (e.g., Klein & Kirkpatrick, 2010; Schoonen & de Glopper, 1996). Students need knowledge about how text components belong to a (historical) genre (e.g., Introduction, how to use criteria for historical significance) and which procedures (e.g., text planning, how to [de]construct arguments about historical significance) are often used by experts when reading or writing (Klein & Boscolo, 2016; Schoonen & de Glopper, 1996). In the field of history education, however, we have limited knowledge about the impact of instruction on the acquisition of procedural knowledge regarding reading (Gross, 2002), writing (van Drie et al., 2018), and the concept of historical significance (van Drie et al., 2013). We need more insight regarding the acquisition of procedural knowledge and whether the quality of students’ written text about historical significance is related to students’ procedural knowledge.

Aim of the study

We aimed to discover the additional value of writing instruction and reading instruction on the quality of students’ written texts in history and on their procedural knowledge. Three questions guided this work:

-

1.

What are the effects of a domain-specific reading-to-write instruction followed by domain-specific writing-strategy instruction (R&W), compared to a repeated domain-specific reading-to-write instruction (R&R), on the quality of students’ written text about historical significance regarding a historical agent?

-

2.

What are the effects of a domain-specific reading-to-write instruction followed by domain-specific writing-strategy instruction, compared to a repeated domain-specific reading-to-write instruction, on students’ procedural knowledge regarding reading, writing, and reasoning about the significance of a historical agent?

-

3.

Does a relationship exist between the quality of students’ argumentative texts about historical significance and their procedural knowledge regarding reading, writing, and reasoning about the significance of a historical agent?

Based on these questions, we formulated the following hypotheses. First, we expected that students in both conditions would write significantly better texts at the posttest compared to the pretest. Second, we hypothesized that regarding the quality of the argumentative texts, students in the R&W condition would make significantly more progress between the pretest and the posttest, compared to students in the R&R condition. Third, we expected that students in both conditions would demonstrate more procedural knowledge at the posttest compared to the pretest. Fourth, we expected that students in the R&W condition would demonstrate significantly more procedural knowledge in writing about historical significance at the posttest, compared to students in the R&R condition. Finally, we expected a significant positive relationship between the quality of the written texts and students’ procedural knowledge.

Method

Participants

This study included 142 10th grade students, preparing for university of applied sciences (N = 91) or university (N = 51; male: 93; female: 47). In order to ensure that possible positive results stemmed from our intervention, all students came from six history classes from one suburban school in a rural area in the Netherlands. All students gave their active consent for participating in this study. All lessons were taught by one teacher (first author), who has a master degree in history and had been teaching history for seventeen years. He participated regularly in professionalization on historical topics and pedagogy (including teaching historical thinking).

Within each class, students were randomly assigned to one of the six teaching groups. Subsequently, three of these teaching groups were randomly assigned to the R&W condition (N = 72) and three to the R&R condition (N = 70). The overall class size varied between 19 and 29 students.

In previous years, students had lessons on the topics chosen for this intervention study (Columbus and Napoleon). Consequently, we expected that students would have some contextual knowledge. The relevant time period, was taught just before the intervention. According to the formal attainment goals in the Netherlands, students must understand the interpretive nature of history, but this is not assessed in a detailed manner in the central exam and is often not explicitly taught. So, we expected students to have only superficial knowledge of the interpretive nature of history. The concept of historical significance and competencies regarding reading or writing historical accounts are not explicitly mentioned in the Dutch curriculum (CvtE, 2018).

Materials and interventions

For this study, we developed two interventions consisting of five lessons each. All lessons were developed by the first author and discussed with the second and third author, which led to small changes. The topic of the first intervention was Columbus and the second was Napoleon. Both topics were closely related to the topics covered in the classes. As a part of the intervention, students were asked to write a text in which they described the contrasting perspectives of two historians regarding the significance of a historical agent. Students were also asked to develop a claim concerning the significance of this agent and to substantiate this claim with explicit arguments (Appendix A). This type of text is called historical discussion (Coffin, 2006).

In both interventions, all students received the same materials: two texts (1) one contained the perspective of a nineteenth century historian who described a historical agent from a nationalistic perspective and (2) another which contained the critical perspective from a twentieth century historian regarding the same historical agent. All text were written in a narrative style. Historical arguments were often not explicitly presented in such a text. For example, several historical events were emphasized by the author by calling them ‘of great importance’ or ‘long lasting effects’. Counterfactual evidence was placed in the background by calling the consequences ‘temporally’. The texts were not used as examples of good historical argumentation. The reading to write instruction in both interventions supported students in identifying interpretative language, the message of the authors and how the authors applied criteria for historical significance. Materials also included biographical highlights of the historical agent in question and some background information about the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

All materials were developed by the first researchers and discussed in the research group, which led to minor adaptions. A Flesch-Kincaid readability test (Kincaid et al., 1975) varied from grade 10.0 to 12.2, which means that all text were challenging, but appropriate for this grade level.

Commonalities and differences between both conditions During the first intervention, the R&W condition received a reading-to-write instruction, and during the second intervention, the R&W condition received a reading- and writing-strategy instruction. In contrast, the R&R condition received a reading-to-write instruction during both interventions. A general overview about which form of instruction both conditions received during the school year and which historical agents were discussed is presented in Table 1.

Reading-to-write instruction The reading-to-write instruction was given to both conditions in Intervention 1 and to the R&R condition in Intervention 2. The general structure of the lessons of the reading-to-write instruction was as follows. During the first lesson, the focus was on the concept of historical significance and on the importance of perspectives on the past. In the second lesson, students received instruction about interpretative language—on how to ask metacognitive questions while reading (e.g., “what is the authors’ message,” “how is the authors’ reasoning constructed,” and “how is the author influenced by the historical context”?) and on how an author applied criteria for historical significance. For example, students were asked to underline interpreting words like “for centuries” and “important”. During the second part of the lesson, students used this knowledge while reading a historical account. Students applied their knowledge about reading in the third lesson, when they independently read the texts. The structure (elements of the introduction, body, and conclusion) of the texts was discussed during the fourth lesson, using a mentor text. Students wrote their text in the last lesson. The teacher made no remarks about writing or applying knowledge of texts while writing.

Writing-strategy instruction Only the R&W condition received this instruction during Intervention 2 (Napoleon). The first lesson contained the same elements as the reading-to-write instruction (historical significance and historical perspectives). During the second lesson, students’ knowledge was reactivated and students applied this knowledge independently (without prompts or whole-class discussion) in small groups while reading both accounts, discussing and answering the questions regarding message of the author, how the message was constructed, and historical context (Intervention I). During the third lesson, students received instruction about text components of the historical discussion (introduction, body, conclusion). This instruction was domain-specific due to the attention, for example, to introduce in the introduction ones position on the significance of the historical agent, and to discuss the development in thinking about a historical agent in the main paragraphs. The teacher modeled how to write an introduction and conclusion, and students independently wrote these parts of a text, but focused on another topic. Instruction on how to construct historical arguments regarding historical significance was provided during the fourth lesson. The teacher, discussed how to write historical arguments (containing a claim supported with arguments. This instruction was also domain-specific due to the attention to, for example, arguments related to the impact of a historical person on the long term. The teacher also modeled how to write (counter)arguments and rebuttals in history, after which students wrote some historical arguments together in small groups. This lesson concluded with examples of relevant language for historians related to historical significance and historical perspectives (e.g., leading to, important, in that time). Students wrote their texts during the last lesson.

A general overview about both methods of instruction is presented in Table 2.

Research instruments

In order to investigate the effects of our interventions, we measured improvement in writing and students’ procedural knowledge.

Text quality As a pretest and posttest, students were asked to write an argumentative text in order to measure text quality. Students were tasked to describe how the assignment of historical significance to a historical agent has changed since 1800 and to develop a unique and substantiated claim about the significance of a historical agent. This type of texts fits in with the genre ‘historical discussion’ (Coffin, 2006). At the pretest, students were asked to write an argumentative text about the Roman emperor Constantine I (ca. 280–337). At the posttest, students wrote a text about the British colonist Cecil Rhodes (1853–1902). In order to fulfill the tasks, students received two historical accounts by two historians, who evaluated the historical agent in different ways. These texts were written in the same style as the intervention texts. Table 3 shows the results of a Flesch-Kincaid readability test (Kincaid et al., 1975) and we concluded that all texts that were used in the intervention lessons were on an appropriate level. In addition, all students received additional sources: background information about the historical context in which both historians lived and some biographical highlights.

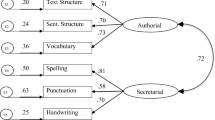

Procedural knowledge of reading, reasoning, and writing In order to measure students’ procedural knowledge, we used an adapted version of an open knowledge test, developed by Schoonen and de Glopper (1996), as a pretest and as a posttest. Students were asked to provide recommendations to a classmate in order to read historical accounts about the significance of a historical person and to write a text about the significance of a historical person (Appendix B). We also used this test in an earlier study (van Driel et al., 2022). This procedural knowledge test includes lower aspects (e.g., punctation) as well as higher aspects of procedural knowledge (e.g., “relate the author to the historical context”).

Procedure

All data were gathered during the 2019–2020 school year, in the period between October and May. All students filled out the pretest one week before the start of the first intervention lessons. After three months, Intervention 2 took place. Students filled out the posttest one week after completing the second lesson unit.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, all schools in the Netherlands were closed on March 16th, 2020. Consequently, some parts of the intervention (the last two lessons of Intervention 2 and the posttest) were provided in an online learning environment. In order to ensure that all students wrote their texts independently, the teacher stressed that the aim was to investigate the quality of written texts and not to assess their texts with a grade. In addition, students were asked to engage their microphone and camera so that the teacher could verify whether students only used the materials of our intervention and whether they worked independently. All students, except a few who encountered technical problems, complied with this request.

Implementation fidelity

We used three instruments to measure the fidelity of implementation: (1) We developed a detailed lesson plan for both conditions, (2) a detailed description was made after each lesson in order to compare the lesson with the original plan, and (3) all available student booklets were checked in order to verify whether they did the assignments as intended.

Based on these data, we can conclude that both interventions were conducted as intended. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, however, some small group assignments were changed into individual assignments. Based on a pattern of different student responses to assignments, we noticed some differences between whole-class discussions across all groups. In one class, for example, students’ answers were more related to moral issues (regarding inequality caused by Columbus), compared to other classes, which were focusing on the significance of Columbus in the sixteenth century. However, all important activities (e.g.; discussing metacognitive questions) were implemented as intended. Students in the R&R-condition filled out 65% (lesson unit 1) and 84% (lesson unit 2) of all assignments; students in the R&W-condition 72% (lesson unit 1) and 73% (lesson unit 2).

Analysis

Quality of written texts All texts (pretest, Lesson Unit 1, Lesson Unit 2, posttest) were coded using an adapted version of a previously developed coding scheme (van Driel et al., 2022). This coding scheme is highly domain-specific. This coding scheme contains main categories focusing on Structure (subcategories: Introduction, Body, and Conclusion), General Writing Aspects (subcategories: Audience-Orientated Writing and Coherence), and Reasoning About Significance (subcategories: Addressing Different Perspectives, Using the Historical Context, Use of Criteria for Significance, and the Use of Historical Facts and Concepts). The complete coding scheme is presented in Appendix C. Students are expected to write a historical discussion (Coffin, 2006). This means that the main category structure is operationalized in a domain-specific manner. For example, our rubric required to include a description of historical perspectives in the body of the text. A historical perspective, requires historians’ arguments and information about the historical context of the historian. Furthermore, students received a higher score for their introduction when they included a position on the significance of the historical agent. After three training sessions, in which the coding scheme was discussed, the first author and a research assistant independently coded approximately 18% of all texts, equally taken from both conditions and tasks (pretest, Intervention 1, Intervention 2, posttest). The calculated Cohen’s Kappa for all subcategories varied between 0.67 and 0.78, which is considered acceptable (Field, 2018). All other texts were coded by the first author.

The calculated Cronbach’s Alfa for the various measurement moments were 0.56, 0.66, 0.75, and 0.69 for the pretest, Intervention 1, Intervention 2, and posttest, respectively. The scores at the pretest showed a relatively low reliability. Given the limitation of Cronbach’s Alfa (Field, 2018), we decided to consider our coding scheme as a coherent construct.

A Shapiro–Wilk test showed that, except for the pretest, all data fit the assumption of normality. We used a Mann–Whitney test to check differences between both conditions. The Mann–Whitney test showed no differences at the pretest between the R&W condition and the R&R condition (p = 0.20). We used repeated measures to examine possible differences between the conditions. The independent variable (between subjects) was the type of instruction: R&W versus R&R. The dependent variable was the quality of the written texts. We also included Time as a factor at four levels: pretest, Intervention 1, Intervention 2, and posttest.

Procedural knowledge All data were coded using a previously developed coding scheme, which contained elements regarding reading, reasoning about historical significance, and writing (van Driel et al., 2022). The complete coding scheme is presented in Appendix D. After a training session, the first author and a research assistant independently coded approximately 18% of all recommendations, equally taken from pretest and posttest and from both conditions. The calculated Cohen’s Kappa was 0.90, which is considered good (Field, 2018). A Shapiro–Wilk test showed that the data did not fit the assumption of normality. We decided to use a Wilcoxon test to examine differences between both conditions as well as the progression. No differences were found between both conditions at the pretest regarding the total amount of procedural knowledge, p = 0.78, nor for the main categories, which included reasoning about significance, p = 0.59, reading, p = 0.30, and writing, p = 0.27.

Missing data All missing data were excluded listwise, which altered the number of participants.

Results

Quality of written texts

All mean scores with respect to the quality of the written essays are presented in Table 4. This table shows considerable improvement in both conditions at almost all subcategories, with an exception of the subcategory ‘conclusion’ in the R&R condition. An example of a text (R&W condition) is presented in Appendix E.

Our hypothesis was that the quality of the written texts would improve in both conditions from pre- to posttest (Hypothesis 1) but that students in the R&W condition would show significantly more improvement compared to students in the R&R condition (Hypothesis 2). Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effect of Time, χ2(5) = 22.20, p < 0.05. Therefore, we corrected the degrees of freedom using Greenhouse–Geisser estimates of sphericity, ε = 0.90 for the main effect of Time. There was a significant effect of Time on the overall quality of the written texts, F(2.70, 305.17) = 133.22, p = 0.00, r = 0.55. This effect size is considered large (Field, 2018). The overall quality of the texts increased linearly over the course of four measures (pretest, Intervention 1, Intervention 2, and posttest). There was also a significant main effect of the type of intervention (R&W, R&R) on the quality of the written texts, F(1, 113) = 10.19, p = 0.00, r = 0.29.

This effect size can be considered small. In addition, there was a significant interaction effect between Time and Condition, F(2.70, 305.17) = 2.97, p = 0.037, r = 0.10. This effect size can be considered small, but we found a large effect size (see also Fig. 1) for the first hypothesis (improvement over the course of four measures). These results confirm our first and second hypotheses.

In order to gain more detailed insight, we used a MANOVA to explore differences between both conditions with respect to the posttest scores on text structure, general writing aspects, and reasoning about historical significance. At the pretest, we found no significant differences between the conditions: text structure, p = 0.05, general writing aspects, p = 0.49, and reasoning about historical significance, p = 0.55. At posttest, we found a significant difference between both conditions with respect to text structure regarding the genre historical discussion, F(1, 124) = 18.35, p = 0.00. Students in the R&W condition scored significantly higher on text structure than students in the R&R condition. No significant differences were found with respect to general writing aspects, p = 0.19, or reasoning about historical significance, p = 0.68.

Procedural knowledge

The general results regarding the acquisition of procedural knowledge, including the main categories, are presented in Table 5.

For both conditions, we assumed that the total amount of procedural knowledge would increase (Hypothesis 3). With respect to the R&W condition, the amount of procedural knowledge at the posttest (Mdn = 11.00, SD = 5.64) was significantly higher than at the pretest (Mdn = 3.50; SD = 3.12), z = − 6.65, p = 0.00, r = − 0.81. This effect size is considered large (Cohen, 1988). In the R&R condition, a Wilcoxon test showed that, compared to the pretest (Mdn = 3.00, SD = 2.37), the total amount of procedural knowledge was significantly higher at the posttest (Mdn = 8.50, SD = 4.80), z = = − 5.97, p = 0.00, r = − 0.77. This effect size is considered large (Cohen, 1988). A Wilcoxon test also showed a significant difference between both conditions at the posttest (R&W, Mdn = 11.00, SD = 5.64; R&R, Mdn = 8.50, SD = 4.80), z = − 2.91, p = 0.004, r = − 0.26. This effect size is considered small (Cohen, 1988). Students in the R&W condition scored significantly higher than students in the R&R condition. This confirmed our third hypothesis.

At the posttest, we also expected significant differences between both conditions regarding procedural knowledge about writing and no significant differences with respect to reasoning about significance and reading (Hypothesis 4). With respect to reasoning about significance, however, we found a significant difference between the R&W condition (Mdn = 2.00, SD = 2.02) and the R&R condition (Mdn = 1.00, SD = 1.54), z = − 2.20, p = 0.028, r = 0.19. This effect size is considered small (Field, 2018). No significant differences were found regarding reading (p = 0.14) and writing (p = 0.10). Our fourth hypothesis cannot be confirmed.

Correlation between procedural knowledge and text quality

We assumed that students’ procedural knowledge would positively correlate with the quality of written texts (Hypothesis 5). We found a weak-to-moderate relationship between the amount of procedural knowledge and the quality of written texts in both conditions at the posttest—regarding the R&W condition (N = 65), Pearson’s r = 0.494, p = 0.00, and the R&R condition (N = 55), Pearson’s r = 0.340, p = 0.01. These findings confirm Hypothesis 5.

In order to gain more detailed insight, we explored whether procedural knowledge of reasoning, reading, and writing correlated with text quality. In the R&W condition, we found positive correlations between text quality and both procedural knowledge of reasoning, Pearson’s r = 0.280, p = 0.02, and writing, Pearson’s r = 0.404, p = 0.00. No significant correlation was found for procedural knowledge of reading and text quality, Pearson’s r = 0.117, p = 0.35. In the R&R condition, we found a positive correlation between procedural knowledge of writing and text quality, Pearson’s r = 0.349, p = 0.00. No significant correlations were found between text quality and both procedural knowledge of reasoning, Pearson’s r = 0.067, p = 0.63, and reading, Pearson’s r = − 0.026, p = 0.85.

Discussion and conclusion

This experimental study aimed to investigate the impact of a reading-to-write instruction followed by writing-strategy instruction, compared to a repeated reading-to-write instruction, with respect to the quality of written texts and procedural knowledge regarding reasoning about significance, reading, and writing. Students in the R&W condition first received a reading instruction in the form of a writing task followed by a writing-strategy instruction, and students in the R&R condition received two reading instructions in the form of a writing task.

Regarding the quality of written texts (historical discussion), we expected significant improvement from pretest to posttest in both conditions. Our results confirmed this expectation, which is in line with earlier research: Reading instruction has a positive effect on text quality (Fitzgerald & Shanahan, 2000; Graham & Perin, 2007; Graham et al., 2018; van Driel et al., 2022; Wissinger et al., 2020). However, when a domain-specific reading instruction was followed by domain-specific writing-strategy instruction, students wrote higher scoring texts. In particular students scored significantly higher on text structure of the genre historical discussion. Based on the scores on the sub variables (Table 4), this might be explained in two ways. First, due to the instruction on structuring the text by writing an introduction, body and conclusion, students in the R&W condition may have written more complete texts (with a clearly distinguishable introduction, a body, and conclusion), compared to students in the R&R condition. This is an effect on a more generic aspect of text quality. Second, due to the instruction on how to include your position (claim) on the significance of the historical agent in the introduction, students in the R&W condition may have written better introductions. This is an effect on a more domain-specific aspect of text quality.

We did not find a significant difference between both conditions regarding the main category reasoning about significance. In both conditions we paid explicit attention to criteria of historical significance. However the writing instruction also focused on including historians’ perspectives and criteria of significance. That no significant differences were found could be related to the coding scheme that perhaps was not sensitive enough to catch differences in the use of language related to those criteria. In the writing instruction we addressed the use of language to describe the historical significance of a person. This was, however, not included in our coding scheme.

With respect to the acquisition of procedural knowledge regarding reading, writing, and reasoning about historical significance, students in both conditions improved significantly from pretest to posttest. Contrary to our expectations, however, the difference between both conditions was found in the amount of procedural knowledge regarding reasoning about historical significance and not (as we expected) regarding procedural knowledge of writing. Finally, we found a small but positive correlation between procedural knowledge and the quality of written texts, which has not always been found in prior research (van Drie et al., 2018, van Drie et al. 2021).

Although a lot of research regarding the relationship between procedural knowledge and the quality of written texts exists in this field of research, our study differs from other studies cited. In contrast with previous research, our study contains two interventions sequentially. Perhaps we found a positive correlation because our study provided opportunities for students to forget and subsequently to reactivate and apply their procedural knowledge, which is associated with better learning (Bjork & Bjork, 2019). Although we expected to find differences between both conditions regarding procedural knowledge of writing, we did not. Perhaps more extended instruction about writing is needed. More research is also needed to gain a better understanding regarding the role of procedural knowledge.

We must take into account several limitations of this study. First, the last part of the intervention took place during the lockdown caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. For that reason, some intervention lessons took place in an online learning environment, so certain small group assignments were changed into individual assignments as well as two texts. One text was written after the second intervention, and the posttest was written in an online learning environment. Despite our efforts, it is not clear how this lockdown affected the outcomes of our study. It is reasonable to believe that the lockdown may have had a negative impact on the learning outcomes (Engzell et al., 2021). Second, we did not measure students’ historical background knowledge or interest in the chosen topics, which could have been of influence on the outcomes (e.g., Nye et al., 2018; O’Reilly et al., 2019; Tyner & Kabourek, 2020). Although we used the same task format and type of materials (background information and two contrasting historical accounts), the topic of the tests differed. Students could have different interest in and background knowledge of Constantine I and Cecil Rhodes, which might have influenced the outcomes Also, the historical period the agents lived in could differ in complexity.

In addition, all students belonged to the same school, followed the same curriculum, and all students were randomly assigned to a teaching group and condition. Therefore, we assumed that there were no differences between both conditions. Third, participating students came from one school in the Netherlands and were taught by one teacher (first author) in order to ensure that results stem from our intervention, but this means that we should be careful about generalizing the outcomes. Finally, bias may have arisen because one of the researchers, who is a history teacher at the school, taught all the lessons. However, we attempted to minimize this bias by detailed lesson plans, and according to the fidelity check, no deviations where found.

This study has some implications for future research. First, researchers in history education could compare—given the difference regarding procedural knowledge on reasoning about historical significance—the reading and writing instruction with the effects of a singular instruction about historical significance on writing. How do these kinds of instructions contribute to students’ knowledge of a specific genre? Second, future research also should take into account students’ background knowledge about and interest in the topic at hand, as well as the perceived complexity of the task.

Given students’ struggles with goal-orientated reading in the Netherlands as well as in other (western) countries (OECD, 2019), this study provides some implications on how to teach reading and writing in history classrooms, to which a limited number of teachers pay attention (Gillespie et al., 2014). The lesson units, developed for this study, could be used as examples of how to construct lessons in history education. The most important implication might be that teachers could demonstrate how historians use language, while constructing a convincing interpretation of the past, and could highlight the influence of the historical context on historical interpretations. In addition, teaching students how to apply domain-specific reading and writing strategies might enable them to develop understanding of historical accounts as contextualized perspectives on the past.

Although both of our instructions had different impacts, overall, we may conclude that reading instruction has a positive impact on the quality of written texts. However, if additional writing instruction is provided, then the quality of the written texts becomes even better. Reading instruction also helps students to acquire procedural knowledge regarding reading historical accounts, reasoning about historical significance, and writing argumentative texts about historical significance. Additional writing-strategy instruction is even more helpful.

References

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2019). Forgetting as the friend of learning: Implications for teaching and self-regulated learning. Advances in Physiology Education, 43, 164–167. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00001.2019

Cercadillo, L. (2001). Significance in history: Students’ ideas in England and Spain. In A. Dickinson, P. Gordon, & P. Lee (Eds.), Raising standards in history (pp. 116–145). Education Woburn Press.

Cercadillo, L., Chapman, A., & Lee, P. (2017). Organizing the past: Historical accounts, significance and unknown ontologies. In M. Carretero, S. Berger, & M. Grever (Eds.), Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education (pp. 529–552). Palgrave Macmillan.

Chapman, A. (2011). Historical Interpretations. In I. Davies (Ed.), Debates in history teaching (pp. 96–108). Routledge.

Coffin, C. (2006). Historical discourse. The language of time, cause and evaluation. London, England: Continuum.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Commissie voor Toetsing en Examens (CvTE). (2018). Syllabus centraal examen 2020. Geschiedenis HAVO. Utrecht: commissie voor Toetsing en Examens [Syllabus central exam 2020. History HAVO. Utrecht: Committee for Assessment and Examination].

Crowhurst, M. (1990). Reading/writing relationships: An intervention study. Canadian Journal of Education/revue Canadienne De L’éducation, 15, 155–172. https://doi.org/10.2307/1495373

De La Paz, S. (2005). Effects of historical reasoning instruction and writing strategy mastery in culturally and academically diverse middle school classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(1), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.139

De La Paz, S., & Felton, M. (2010). Reading and writing from multiple sources in history: Effects of strategy instruction. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35, 174–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.03.001

De La Paz, S., Wissinger, D. R., Gross, M., & Butler, C. (2022). Strategies that promote historical reasoning and contextualization: A pilot intervention with urban high school students. Reading and Writing, 35, 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10183-0

De la Paz, S., Monte-Sano, C., Felton, M., Croninger, R., Jackson, C., & Piantedosi, K. (2017). A historical writing apprenticeship for adolescents: Integrating disciplinary learning with cognitive strategies. Reading Research Quarterly, 52(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.147

Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. D. (2021). Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(17), e2022376118.

Fallace, T. D. (2007). Once more unto the breach: Trying to get preservice teachers to link historiographical knowledge to pedagogy. Theory & Research in Social Education, 35(3), 427–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2007.10473343

Fallace, T., & Neem, J. N. (2005). Historiographical thinking: Towards a new approach to preparing history teachers. Theory & Research in Social Education, 33(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2005.10473285

Fang, Z. (2016). Teaching close reading with complex texts across different content areas. Research in the Teaching of English, 51(1), 106–116.

Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using SPSS (5th ed.). New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Fitzgerald, J., & Shanahan, T. (2000). Reading and writing relations and their development. Educational Psychologist, 35(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3501_5

Gillespie, A., Graham, S., Kiuhara, S., & Hebert, M. (2014). High school teachers’ use of writing to support students’ learning: A national survey. Reading and Writing, 27(6), 1043–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-013-9494-8

Goldman, S. R., Greenleaf, C., Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M., Brown, W., Ko, M. L. M., Emig, J. M., George, M. A., Wallace, P., Blaum, D., & Britt, M. A. (2019). Explanatory modeling in science through text-based investigation: Testing the efficacy of the Project READI intervention approach. American Educational Research Journal, 56(1), 1148–1216. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831219831041

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 445–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445

Graham, S., Liu, X., Bartlett, B., Ng, C., Harris, K. R., Aitken, A., Barkel, A., Kavanaugh, C., & Talukdar, J. (2018). Reading for writing: A meta-analysis of the impact of reading interventions on writing. Review of Educational Research, 88(2), 243–284. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317746927

Gross, A. (2002). Testing the validity of a meta-reading model. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 2(2), 177–178. https://doi.org/10.1891/194589502787383371

Hofer, B. K. (2004). Epistemological understanding as a metacognitive process: Thinking aloud during online searching. Educational Psychologist, 39, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3901_5

Houwen, A., van Boxtel, C., & Holthuis, P. (2020). Dutch students’ understanding of the interpretative nature of textbooks when comparing two texts about a significant event in the development of democracy. History Education Research Journal, 17(2), 214–228. https://doi.org/10.14324/HERJ.17.2.06

Hunt, M. (2000). Teaching historical significance. In J. Arthur & R. Phillips (Eds.), Issues in history teaching (pp. 39–53). Routledge.

Innes, M. (2020). Dynamic literacies and democracy: A framework for historical literacy. In C. W. Berg & T. M. Christou (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of history and social studies education (pp. 597–620). Palgrave Macmillan.

Jouhar, M. R., & Rupley, W. H. (2021). The reading–writing connection based on independent reading and writing: A systematic review. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 37(2), 136–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2020.1740632

Kincaid J. P., Fishburne R. P. Jr, Rogers R. L., & Chissom B. S. (1975). Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated readability index, Fog count and Flesch reading ease formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. Research branch Report pp. 8–75, Millington, TN: Naval technical training, U. S. Naval air station, Memphis, TN. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1055&context=istlibrary.

Klein, P. D., & Boscolo, P. (2016). Trends in research on writing as a learning activity. Journal of Writing Research, 7(3), 311–350. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2016.07.03.01

Klein, P. D., & Kirkpatrick, L. C. (2010). A framework for content area writing: Mediators and moderators. Journal of Writing Research, 2(1), 1–46.

Körber, A. (2015). Historical consciousness, historical competencies—and beyond? Some conceptual development within German history didactics. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:10811.

Lévesque, S. (2008). Thinking historically. Toronto University Press.

Levine, S. (2014). Making interpretation visible with an affect-based strategy. Reading Research Quarterly, 49, 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.71

Monte-Sano, C. (2010). Disciplinary literacy in history: An exploration of the historical nature of adolescents’ writing. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 19(4), 539–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2010.4810

NyeButt, B. S. M., Bradburn, J., & Prasad, J. (2018). Interests as predictors of performance: An omitted and underappreciated variable. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 108, 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.003

O’Reilly, T., Wang, Z., & Sabatini, J. (2019). How much knowledge is too little? When a lack of knowledge becomes a barrier to comprehension. Psychological Science, 30(9), 1344–1351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619862276

OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 Results. Combined executive summaries, Vol. I, II, & III. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/Combined_Executive_Summaries_PISA_2018.pdf.

Paul, H. (2017). What defines a professional historian? A historicizing model. Journal of the Philosophy of History, 11, 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1163/18722636-12341322

Paul, H. (2019). The historians as a public moralist: On the Roman origins of a scholarly persona. History and Theory, 59(2), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/hith.12115

Poitras, E. G., & Lajoie, S. P. (2013). A domain-specific account of self-regulated learning: The cognitive and metacognitive activities involved in learning through historical inquiry. Metacognition Learning, 8, 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-013-9104-9

Reisman, A. (2012). Reading like a historian: A document-based history curriculum intervention in urban high schools. Cognition and Instruction, 30(1), 86–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2011.634081

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004). The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schleppegrell, M., & de Oliveira, L. (2006). An integrated language and content approach for history teachers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 5(1), 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2006.08.003

Schoonen, R., & de Glopper, K. (1996). Writing performance and knowledge about writing. In G. Rijlaarsdam, H. van den Bergh, & M. Couzijn (Eds.), Theories, models & methodology in writing research (pp. 87–107). Amsterdam University Press.

Seixas, P., & Morton, T. (2012). The big six: Historical thinking concepts. Nelson.

Stoel, G. L., van Drie, J. P., & van Boxtel, C. A. M. (2017). The effects of explicit teaching of strategies, secondorder concepts, and epistemological underpinnings on students’ ability to reason causally in history. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(3), 321–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000143

Trapman, M., van Gelderen, A., van Steensel, R., van Schooten, E., & Hulstijn, J. (2014). Linguistic knowledge, fluency and meta-cognitive knowledge as components of reading comprehension in adolescent low achievers: Differences between monolinguals and bilinguals. Journal of Research in Reading, 37(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2012.01539.x

Tyner, A., & Kabourek, S. (2020) Social studies instruction and reading comprehension: Evidence from the early childhood longitudinal study. Thomas B. Fordham Institute. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/resources/social-studies-instruction-and- reading-comprehension (2021).

van Drie, J., van Boxtel, C., & van der Linden, J. L. (2006). Historical reasoning in a computer-supported collaborative learning environment. In A. M. O’Donnell, C. E. Hmelo, & G. Erkens (Eds.), Collaborative learning, reasoning and technology (pp. 265–296). Lawrence Erlbaum.

van Drie, J. P., van Boxtel, C. A. M., & Stam, B. (2013). Discussing historical significance in the classroom: “But why is this so important.” International Journal of historical learning, teaching and research, 12(2), 146–168.

van Drie, J. P., Braaksma, M., & van Boxtel, C. (2015). Writing in history: Effects of writing instruction on historical reasoning and text quality. Journal of Writing Research, 7(1), 123–156. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2015.07.01.06

van Boxtel, C. A. M., & van Drie, J. P. (2018). Historical reasoning: Conceptualizations and educational applications. In S. A. Metzger & L. McArthur Harris (Eds.), The Wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning (pp. 149–176). Wiley-Blackwell

van Drie, J. P., Janssen, T., & Groenendijk, T. (2018). Effects of writing instruction on adolescents’ knowledge of writing and text quality in history. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 18(2), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.17239/L1ESLL-2018.18.03.08

van Drie, J., van Driel, J., & van Weijen, D. (2021). Developing students’ writing in History: Effects of a teacherdesigned domain-specific writing instruction. Journal of Writing Research, 13(2), 201–229. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2021.13.02.01

van Driel, J., van Drie, J., & van Boxtel, C. (2022). Writing about historical significance: The effects of a reading-to-write instruction. International Journal of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.101924

van Gelderen, A., Schoonen, R., Stoel, R. D., de Glopper, K., & Hulstijn, J. (2007). Development of adolescent reading comprehension in language 1 and language 2: A longitudinal analysis of constituent components. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 477–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.477

Wansink, B., Akkerman, S., Zuiker, I., & Wubbels, T. (2018). Where does teaching multiperspectivity in history education begin and end? An analysis of the uses of temporality. Theory and Research in Social Education, 46(4), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2018.1480439

Wineburg, S. (1991). Historical problem solving: A study of the cognitive processes used in the evaluation of documentary and pictorial evidence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.83.1.73

Wineburg, S. (1998). Reading Abraham Lincoln: An expert/expert study in the interpretation of historical texts. Cognitive Science, 22, 319–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0364-0213(99)80043-3

Wissinger, D. R., & De La Paz, S. (2016). Effects of critical discussions on middle school students’ written historical arguments. Journal of Educational Psychology, 8(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000043

Wissinger, D. R., De La Paz, S., & Jackson, C. (2020). The effects of historical reading and writing strategy instruction with fourth- through sixth-grade students. Journal of Educational Psychology., 113(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000463

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Columbus Day is celebrated on the second Monday in October in the United States. This day has been officially a national holiday since 1937. However, not all States celebrate this day. Some States find this day an insult to the descendants of the original inhabitants of the United States. The state of South Dakota celebrates this day but calls it “Native American Day.”

The US government wonders whether Columbus Day should be celebrated as a national

holiday. A historical committee has been set up to investigate this issue. The committee considers these questions:

-

1.

How has the assigned significance to Columbus developed over time?

-

2.

Should Columbus Day be celebrated as a national day or not?

In order to make a decision about Columbus Day, you as a historian are asked to answer these questions.

Write an essay to the committee in which you indicate to what extent Columbus is historically

important. Also pay attention to how thinking about Columbus has developed over time. Then give a reasoned opinion on whether Columbus Day should be celebrated as a national holiday or not.

Use the texts in which two historians assign significance to Columbus (Text 1 and 2) and a text with background information (background to the texts). Finally, you will find a brief biography about Columbus.

You can also use the information from the lessons. Write an argumentative text in which you answer the above questions. There is no prescribed length of the text. Attempt to write a text of at least 250 words. For this assignment you have one lesson.

Appendix B

Text structure

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Introduction | None of the characteristics listed alongside are present / There is no introduction | There is an introduction and Mentions a position on historical agents in the introduction Or Introduces the subject: the commemoration of historical agents | There is an introduction and Mentions a position on historical agents in the introduction and Introduces the subject: the commemoration of historical agents | Mentions a standpoint on historical agents in the introduction and introduces the subject: commemorating historical agents but does not yet mention arguments in the introduction. Introduction invites readers to read |

Body | The development in thinking about historical agents is discussed Or The importance of historical agents from the perspective of the twenty-first century | The development in thinking about historical agents is discussed. This development is moderately described and On the importance of historical agents from the perspective of the twenty-first century supported by an argument | The development in thinking about historical agents is discussed. This development is well described and The importance of historical agents from the perspective of the twenty-first century supported by several arguments | The development in thinking about historical agents is discussed. This development is well described and On the importance of historical agents from the perspective of the twenty-first century supported by several arguments, there is a counter argument that is being refuted |

Conclusion | There is a conclusion about commemorating historical agents, but standpoint or argumentation are not repeated / There is no conclusion | Concludes with a conclusion about the commemoration of historical agents and 2 of the following: Repeats position Repeats main arguments briefly and powerfully The conclusion is convincing Does not mention any new arguments in the conclusion | Concludes with a conclusion about the commemoration of historical agents and 3 of the following: Repeats position Repeats main arguments briefly and powerfully The conclusion is convincing Does not mention any new arguments in the conclusion | Concludes with a conclusion about the commemoration of historical agents in which the point of view and main arguments are briefly and powerfully repeated. The conclusion is convincing. Does not mention any new arguments in the conclusion |

General writing

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Audience-orientated writing | Does not apply the conventions belonging to the type of text (letter) at all (it is not a letter). The style does not show understanding for the reader (too informal or too formal) | Hardly applies the conventions associated with the type of text (letter) (it is a very informal letter) Is generally inconsistent in the use of a style that shows understanding for the reader | Uses the conventions belonging to the type of text (letter) largely correctly (it is a letter, but formal conventions are not used correctly everywhere) Overall, the author is able to use a style (not too informal and not too formal) that shows understanding for the reader | Uses the conventions belonging to the type of text (letter) correctly (it is a formal letter) Overall, the author is able to use a style that shows understanding for the reader. The style makes the text attractive to read (e.g., by varying sentences, attractive beginning and ending) |

Coherence | Consistency in the text and within compound sentences is regularly not clear. The author's line of thought cannot always be followed. There is no, or no good paragraph classification. Errors with referrals and linking words occur regularly | Coherence in the text and within compound sentences is sometimes clear and sometimes not clear. The author's line of thought is generally fairly clear, but not always. There is a reasonably good paragraph classification. Errors with reference and linking words occur occasionally | Coherence in the text and within compound sentences is usually clear. The author's line of thought is generally clear. There is a good paragraph classification. Reference and linking words are used correctly | Coherence in the text and within compound sentences is clear. Paragraphs are linked into a coherent whole. The author's line of thought is clear and logical and consistently ordered. The connection between and within sentences is well indicated by the use of correct references and connection words |

Reasoning about significance

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Perspectives on historical agents | A perspective on historical agents is distinguished | Two different perspectives on historical agents are distinguished | Two different perspectives on historical agents are distinguished and understood from the historical context | Two different perspectives on historical agents are distinguished and the sources are mentioned and understood from the historical context |

Use historical context | The historical context was not used to comprehend or largely incorrect | One aspect of historical agents actions was more or less correctly contextualized | Two aspects of historical agents actions were more or less correctly contextualized | Two or more aspect of historical agents actions were contextualized correctly |

Use criteria significance | Criteria for significance are not or not correctly used | One criterion for significance is used implicitly or explicitly | Several criteria for significance are implicitly stated | Several criteria for significance are explicitly mentioned |

Use historical facts and concepts | In terms of content, the reasoning followed contains errors | In terms of subject matter, the reasoning followed is broadly correct but contains errors on a detailed level | The reasoning followed is correct in terms of subject matter, but there is no/narrow use of subject terms and/or historical facts | The reasoning followed is correct in terms of subject matter and use is made of subject terms and/or historical facts Attention is also paid to metahistorical concepts |

Appendix C

Pre- and posttest procedural knowledge reading, reasoning about historical significance, and writing.

A good friend would really like to get a good grade for history. This friend asked you for help with an assignment. He/she must read a number of texts and write an essay based on these texts.

The assignment that your friend has to do is write an essay in which he or she explains how historians’ interpretation of this significant historical person has developed though time.

Write an email to this friend in which you give tips on how to read historical texts and how to write a letter in the context of this assignment.

Appendix D

Recommendations reading | Examples |

|---|---|

Content text | Identify arguments in this particular account |

Reading process | Underline important things parts of the text |

Recommendations writing | |

Product | Provide historical evidence for your opinion |

Process | Make a chart with the views of the historians |

Recommendations reasoning about historical significance | |

Background author | Mind how the author is influenced by his political background |

Comparisons accounts | Compare historians from different times What did it cause in that time? What happened in that time? |

Criteria significance | |

Other aspects of reasoning about significance | |

Information | |

Gather information | Find historical sources from that time |

Other | |

Other | Get started on time |

Appendix E

Since 2015, there has been a discussion about the statue of a former student, Cecil Rhodes, which stands next to your university. You have asked a number of experts to investigate whether it is still appropriate for the statue of Rhodes to have a place at your university. I will also give my opinion on this. I do this on the basis of texts based on books written by historians Basil Williams (1867–1950) and Brian Roberts (1930–present).

British historian Basil Williams published his book Cecil Rhodes in 1920. In this book, Williams describes the life of Rhodes, and he wants to make clear that Rhodes has been of great significance for the growth of the British Empire. At the time this book was published, many Britons were very much influenced by nationalism; they felt their country had the right to serve over others. Williams mentions many good sides of Rhodes. That, despite setbacks, he was able to earn a lot of money. He also describes that, despite his lack of presence at political meetings, he still had the chance to become prime minister. He formed a cabinet aimed at serving England. Rhodes was always focused on the public interest when he made laws. Thus, Rhodes had great influence in his time. What is striking is that a bill that would allow men of all races to go to university (the bill failed to pass) earned him the nickname Friend of the Natives, but in order to allay political opposition he faced, he passed a law that curtailed the rights of the natives. He also had great influence after his death.

In short, Williams believes that Rhodes has served humanity. He still mentions the bad sides of Rhodes (fascinated by money and very cynical) but places this in the background by writing that he was of great importance for the peace in South Africa. Rhodes was able to connect people, and this makes him a great statesman.

Another British Historian, Brian Roberts, wrote a book in 1988 interpreting Rhodes’ actions. He calls this: Cecil Rhodes, flawed Colossus. Roberts describes how Rhodes made the choice to serve his country at a young age and that was the beginning of his career as an entrepreneur and politician. Roberts is very negative about Rhodes. He accuses Rhodes of illegally competing with his competitors, and I believe he has solid evidence to back this up. Roberts also gives plenty of good examples that Rhodes (almost) succeeded several times in introducing discriminatory legislation and that this shows his derogatory attitude towards the indigenous population. Roberts is very clear that Rhodes cannot be held directly responsible for Apartheid, but he is one of the preparers.

Roberts concludes that Rhodes has already played an important role as an entrepreneur and politician in the expansion of the British Empire. Rhodes was very popular in Africa, but his way of doing business came at the expense of the natives. It was important to him that the Glen Gray Act was passed because it facilitated the administration of South Africa. Roberts does not say that Rhodes was a convinced racist, but he partly blames him for the apartheid system by adopting the Glen Gray Act. This criticism fits the latter part of the twentieth century, when equality was very important.

Today there is more and more attention for figures like Rhodes. Heroes of History; but are they? I think Roberts is justified in questioning how great Rhodes was. So, I completely agree with his reasoning. Rhodes did a lot of good for the expansion of the British Empire, but much of that was done at the expense of the natives. Certainly, in today's world, where the relatives of, for example, the indigenous people of South Africa still suffer negative consequences of the past, where people like Rhodes have had a great influence, we—and certainly a leading educational institution like Oxford University—would not wish for people who have earned their stripes on the backs of others to be immortalized by means of a statue.

I hope that you can see that leaving the statue alone will only hurt people and that you will take the statue away. Cecile Rhodes does not deserve to be immortalized in this way.

I hope that you are able to make a good decision in this complex matter and that I have been able to contribute with my input.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

van Driel, J., van Driel, J. & van Boxtel, C. Writing about the significance of historical agents: the effects of reading and writing instruction. Read Writ (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10404-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10404-0