Abstract

Research documents that managers, on average, withhold bad news and emphasize good news in their public disclosures. We ask whether the same is true in their private communications with credit rating agencies. We study how rating agencies anticipate and react to public information events as a function of their access to rated firms’ private information. We show that, in terms of ratings downgrades, rating agencies exhibit relatively more anticipation and less reaction to negative (compared to positive) public information events when they have more access to private information. Our results are strongest when firms are most optimistic in their public disclosures and are not due to rating agencies focusing their efforts on downside risk. Overall, we find consistent evidence that rated firms provide less optimistic information to rating agencies in their private communications and that this information is reflected in credit ratings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To illustrate, the SEC notes that “as part of Standard & Poor’s surveillance process, the rated company is obliged to furnish complete, timely and reliable information to Standard & Poor’s on an ongoing basis” (https://www.sec.gov/news/extra/credrate/standardpoors.htm, emphasis added). Critics have raised concerns that, despite their access to private information, rating agencies are ineffective, either because they are not timely in processing information or because they are unwilling to issue ratings that reflect that information. We discuss this criticism, which would bias against our finding results, in Section 2.

Examples include the work of Jorion et al. (2005), who use stock price responses to rating changes to infer that rating agencies have relatively more private information after the enactment of Regulation FD; that of Kothari et al. (2009), who use asymmetric responses to good and bad news to infer that firms withhold bad news from investors; and that of Rogers and Stocken (2005), who use the ex post error in management forecasts to infer biased disclosures.

In all of these analyses, we are controlling for the rated firm’s stock return on the event date, whether the event is an earnings announcement or an industry-wide shock. In effect, we are testing whether the rating agency’s response differs based on whether the news is firm-specific or industry-wide, holding constant the magnitude of the news for the individual firm.

For example, Hutton on et al. (2012) find that managers’ information advantage, relative to analysts, lies at the firm level.

For example, Beaver et al. (2006) document that noncertified rating agencies like Egan-Jones are likely to move more quickly than certified rating agencies like S&P. If this difference in behavior were driving our earnings announcement results, we would expect to see the same difference when we look at industry-wide news. In addition, we show that our results are not due to Egan-Jones simply reacting more quickly to new information than S&P; the difference between S&P’s reaction and Egan-Jones’s reaction widens as we look at longer periods following the information event.

The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 removed the express exemption for Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations (i.e., credit rating agencies) from Regulation FD. However, rating agencies continue to receive material nonpublic information from debt issuers under an exemption in Regulation FD for “a person who expressly agrees to maintain the disclosed information in confidence” (§ 243.100(b)(2)(ii)). Conversations with rating agency representatives confirm that these express agreements are commonplace in the post-Dodd-Frank period.

Critics argue that credit ratings do not fully incorporate all available information and point out that markets often anticipate ratings changes. See, for example, Hull et al. (2004), Finnerty et al. (2013), and Norden and Weber (2004). Nonetheless, these and other papers show that markets respond to rating changes, which indicates that the privately informed rating agencies have at least some amount of private information. We show similar evidence of a response to rating changes, as well.

This is similar to the leverage that an audit firm has when auditing publicly traded firms. The threat of a qualified audit opinion gives the auditor greater ability to extract information than what analysts or outside investors could extract.

Managers may also believe that, if they withhold bad news in their public disclosures but reveal that information to the rating agency, investors will not fully infer that negative information from the credit rating. In Section 4, we test whether privately informed credit ratings have the ability to predict returns around future information events.

This nonpublic information can relate to a variety of topics. To illustrate, S&P stated the following in SEC testimony related to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act: “It is common during the credit rating process and ongoing surveillance for companies to provide Standard & Poor’s with non-public information, such as budgets and forecasts, financial statements on a stand-alone basis, internal capital allocation schedules, contingent risks analyses and information relating to new financings, acquisitions, dispositions, and restructurings.” Full testimony can be found at https://www.sec.gov/news/extra/credrate/standardpoors.htm.

In its February 2013 form NRSRO (application for registration as a nationally recognized statistical rating organization), Egan-Jones stated: “The firm collects information regarding the financial information underlying its ratings work solely from publicly available and recognizably reliable sources (Bloomberg, Edgar, and assorted media sources). The firm does not use confidential or other non-public information in its work product.”

Even though we focus on both firm-specific and industry-wide shocks, all of our analyses regress the individual firm’s credit rating changes on the individual firm’s event-period stock return. Our basic question is whether that relation varies with the rating agency (S&P versus Egan-Jones) or the type of event (firm-specific versus industry-wide). Thus our comparison accounts for the fact that industry-wide shocks may differ from firm-specific events. (For example, they may be more or less permanent.) By controlling for the firm-specific returns to each event, those differences should not affect our inferences as long as equity investors are not systematically biased in how they price those events.

We do not require that the individual firm’s stock return exceed a particular threshold to be included in the industry shock sample. Just as many earnings announcement returns are quite small in magnitude, many individual firms’ stock returns will be close to zero on industry shock days.

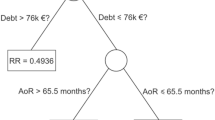

We present the average cross-partial derivative for the Bad_News*Return interaction terms (interaction effect), using the Stata “margins” command. This estimate should be interpreted as the change in the conditional probability of a future downgrade for a change in stock return as stock returns move from positive to negative (Karaca-Mandic et al. 2012).

These fundamentals are total debt divided by total assets, long-term debt divided by total assets, return on assets, interest coverage, beta, the natural logarithm of market capitalization, and the firm’s expected default frequency.

The inference is unchanged if we focus on the regression results without control variables in Columns (1) and (2).

We cannot detect a difference between the coefficients in Columns (5) and (6).

Again, in each case, the independent variable captures firm-specific negative stock return, so the estimated coefficient represents S&P’s sensitivity to a unit of firm-specific news across different types of event dates.

Inferences are unchanged if we focus on the regression results without requiring control variables.

In untabulated results, we also examine the level of S&P versus Egan-Jones ratings prior to information events. S&P’s rating is significantly more likely to be lower than Egan-Jones’s rating when subsequent earnings announcements reveal more negative information. However, there is no evidence of such a relation prior to negative news on industry-wide shock dates. These results are consistent with the changes analyses presented in Tables 3 through 5.

We are not asserting that investors necessarily respond to our estimated private information. It could be the case that investors respond to the public revelation of economic situations in which issuers have disclosed privately to the rating agencies (e.g., mergers, executive turnover, loss of a key customer).

Our regressions include S&P rating level fixed effects, so that low absolute credit ratings are not driving our results.

The variables in the Huang et al. model are earnings before extraordinary items scaled by assets, contemporaneous annual returns, log of market value of equity, book-to-market, standard deviation of monthly stock returns, standard deviation of scaled earnings, the log of the number of years the firm appears on the CRSP dataset, the log of 1+ the number of business segments, the log of 1+ the number of geographic segments, an indicator equal to 0 when earnings are negative, the change in earnings scaled by total assets, analysts’ forecast error, and the analyst consensus estimate for one-year-ahead earnings per share, scaled by stock price. Huang et al. assess future performance and stock returns and conclude that abnormal tone represents managers’ use of disclosure to mislead investors.

For brevity, we do not include comparisons with Egan-Jones in our tone tests. However, we find that the earlier documented differences between S&P and Egan-Jones are most significant for the highest tercile of abnormal tone observations.

References

Aboody, D., & Kasznik, R. (2000). CEO stock option awards and the timing of corporate voluntary disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 29(1), 73–100.

Ahmed, A. S., & Duellman, S. (2007). Accounting conservatism and board of director characteristics: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43(2), 411–437.

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economic Letters, 80(1), 123–129.

Alissa, W., Bonsall, S. B., Koharki, K., & Penn, M. W., Jr. (2013). Firms' use of accounting discretion to influence their credit ratings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 55(2–3), 129–147.

Asquith, P., Beatty, A., & Weber, J. (2005). Performance pricing in bank debt contracts. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40(1–3), 101–128.

Avramov, D., Chordia, T., Jostova, G., & Philipov, A. (2009). Dispersion in analysts’ earnings forecasts and credit rating. Journal of Financial Economics, 91(1), 83–101.

Avramov, D., Chordia, T., Jostova, G., & Philipov, A. (2013). Anomalies and financial distress. Journal of Financial Economics, 108(1), 139–159.

Ball, R., Robin, A., & Sadka, G. (2008). Is financial reporting shaped by equity markets or by debt markets? An international study of timeliness and conservatism. Review of Accounting Studies, 13(2–3), 168–205.

Bao, D., Y. Kim, G. M. Mian, and L. Su. (2018). Do managers disclose or withhold bad news? Evidence from short interest. The Accounting Review, in-press.

Beaver, W. H., Shakespeare, C., & Soliman, M. T. (2006). Differential properties in the ratings of certified versus non-certified bond-rating agencies. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(3), 303–334.

Berger, P. G., & Hann, R. N. (2007). Segment profitability and the proprietary and agency costs of disclosure. The Accounting Review, 82(4), 869–906.

Bhanot, K., & Mello, A. S. (2006). Should corporate debt include a rating trigger? Journal of Financial Economics, 79(1), 69–98.

Bonsall, S. B. (2014). The impact of issuer-pay on corporate bond rating properties: Evidence from Moody’s and S&P’s initial adoptions. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 57(2–3), 89–109.

Bonsall, S. B., Koharki, K., & Neamtiu, M. (2017). When do differences in credit rating methodologies matter? Evidence from high information uncertainty borrowers. The Accounting Review, 92(4), 53–79.

Bruno, V., Cornaggia, J., & Cornaggia, K. J. (2016). Does regulatory certification affect the information content of credit ratings? Management Science, 62(6), 1578–1597.

Bushman, R. M., Smith, A. J., & Wittenberg-Moerman, R. (2010). Price discovery and dissemination of private information by loan syndicate participants. Journal of Accounting Research, 48(5), 921–972.

Chen, S., Chen, X., & Cheng, Q. (2008). Do family firms provide more or less voluntary disclosure? Journal of Accounting Research, 46(3), 499–536.

Chen, T., & Martin, X. (2011). Do Bank-affiliated analysts benefit from lending relationships? Journal of Accounting Research, 49(3), 633–675.

Cheng, Q., & Lo, K. (2006). Insider trading and voluntary disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 44(5), 815–848.

Chung, R., Lee, B. B.-H., Lee, W.-J., & Sohn, B. C. (2015). Do managers withhold good news from labor unions? Management Science, 62(1), 46–68.

Doyle, J. T., Jennings, J. N., & Soliman, M. T. (2013). Do managers define non-GAAP earnings to meet or beat analyst forecasts? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56(1), 40–56.

Finnerty, J. D., Miller, C. D., & Chen, R.-R. (2013). The impact of credit rating announcements on credit default swap spreads. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(6), 2011–2030.

He, J., Qian, J., & Strahan, P. E. (2012). Are all ratings created equal? The impact of issuer size on the pricing of mortgage-backed securities. Journal of Finance, 67(6), 2097–2137.

Healy, P. M., & Wahlen, J. M. (1999). A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons, 13(4), 365–383.

Huang, X., Teoh, S. H., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Tone Management. The Accounting Review, 89(3), 1083–1113.

Hull, J., Predescu, M., & White, A. (2004). The relationship between credit default swap spreads, bond yields, and credit rating announcements. Journal of Banking & Finance, 28(11), 2789–2811.

Hutton, A. P., Lee, L. F., & Shu, S. Z. (2012). Do managers always know better? The relative accuracy of management and analyst forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research, 50(5), 1217–1244.

Ivashina, V., & Sun, Z. (2011). Institutional stock trading on loan market information. Journal of Financial Economics, 100(2), 284–303.

Jiang, J., Harris Stanford, M., & Xie, Y. (2012). Does it matter who pays for bond ratings? Historical evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 105(3), 607–621.

Jorion, P., Liu, Z., & Shi, C. (2005). Informational effects of regulation FD: Evidence from rating agencies. Journal of Financial Economics, 76(2), 309–330.

Jung, B., Soderstrom, N., & Yang, Y. S. (2013). Earnings smoothing activities of firms to manage credit ratings. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(2), 645–676.

Jung, M. J., Naughton, J. P., Tahoun, A., & Wang, C. (2018). Do firms strategically disseminate? Evidence from corporate use of social media. The Accounting Review, 93(4), 225–252.

Karaca-Mandic, P., Norton, E. C., & Dowd, B. (2012). Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Services Research, 47(1), 255–274.

Kothari, S. P., Shu, S., & Wysocki, P. D. (2009). Do managers withhold bad news? Journal of Accounting Research, 47(1), 241–276.

Kraft, P. (2015). Do rating agencies cater? Evidence from rating-based contracts. Journal of Accounting and Economics 59(2–3), 264–283.

Liberty, S. E., & Zimmerman, J. L. (1986). Labor union contract negotiations and accounting choices. The Accounting Review, 61(4), 692–712.

Lougee, B. A., & Marquardt, C. A. (2004). Earnings Informativeness and strategic disclosure: An empirical examination of “pro forma” earnings. The Accounting Review, 79(3), 769–795.

Massoud, N., Nandy, D., Saunders, A., & Song, K. (2011). Do hedge funds trade on private information? Evidence from syndicated lending and short-selling. Journal of Financial Economics, 99(3), 477–499.

McVay, S. E. (2006). Earnings management using classification shifting: An examination of Core earnings and special items. The Accounting Review, 81(3), 501–531.

Nikolaev, V. V. (2010). Debt covenants and accounting conservatism. Journal of Accounting Research, 48(1), 51–89.

Norden, L., & Weber, M. (2004). Informational efficiency of credit default swap and stock markets: The impact of credit rating announcements. Journal of Banking & Finance, 28(11), 2813–2843.

Plumlee, M., Xie, Y., Yan, M., & Yu, J. J. (2015). Bank loan spread and private information: Pending approval patents. Review of Accounting Studies, 20(2), 593–638.

Purda, L. (2007). Stock market reaction to anticipated versus surprise rating changes. Journal of Financial Research, 30(2), 301–320.

Rogers, J. L., & Stocken, P. C. (2005). Credibility of management forecasts. The Accounting Review, 80(4), 1233–1260.

Rogers, J. L., Van Buskirk, A., & Zechman, S. L. C. (2011). Disclosure tone and shareholder litigation. The Accounting Review, 86(6), 2155–2183.

Roychowdhury, S. (2006). Earnings management through real activities manipulation. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(3), 335–370.

Shivakumar, L. (2013). The role of financial reporting in debt contracting and in stewardship. Accounting and Business Research, 43(4), 362–383.

Skinner, D. J. (1994). Why firms voluntarily disclose bad news. Journal of Accounting Research, 32(1), 38–60.

Strobl, G., & H. Xia. (2012). The issuer-pays rating model and ratings inflation: Evidence from corporate credit ratings. Working paper, University of Texas at Dallas and Frankfurt School of Finance and Management.

Zhang, J. (2008). The contracting benefits of accounting conservatism to lenders and borrowers. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(1), 27–54.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lakshmanan Shivakumar (editor), two anonymous reviewers, Ryan Ball, Mei Cheng, Christine Cuny, Ed deHaan, Rahul Vashishtha, and workshop participants at London Business School, the Ohio State University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Texas for helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahn, M., Bonsall, S.B. & Van Buskirk, A. Do managers withhold bad news from credit rating agencies?. Rev Account Stud 24, 972–1021 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-019-09496-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-019-09496-x