Abstract

The US time structure of production during the 2002 through 2009 business cycle is characterized empirically using industry-level input-output data. An industry’s total industry output requirement (TIOR) is proposed as a metric for “roundaboutness”. I find that the time structure of production lengthened following the Federal Reserve’s 2002 expansionary deviation from the Taylor rule and then contracted during the Great Recession. Value added growth in the most-roundabout of US industries accelerated relative to that of the least-roundabout industries. Heading into the Great Recession, value-added growth in the most-roundabout industries contracted early and turned negative in 2007 while value-added growth in the least-roundabout industries remained positive until 2009. The stylized facts of the time structure of production are consistent with Austrian Business Cycle Theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Callahan and Horwitz (2010, p. 220) state: “If the central bank pursues a discretionary, rather than a rule-oriented, monetary policy, then the particular ideas of the chief central banker […] must be taken into account by participants in the markets affected by central bank policy.”

As of this writing, the latest US Department of Labor report is for April of 2011 with the unemployment rate at 9.0 percent.

Similar statements can be derived using an additive value-added assumption in place of (3), i.e., X i+1 = X i + R.

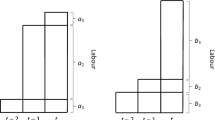

See Barnett and Block (2006) for a critique and, ultimately, an almost complete rejection of the use of Hayekian triangles.

This will be true even if a larger or smaller number of firms allocate their time during the same “calendar time” interval. There are certainly analogs between the underlying intuition my using the TIOR and Skousen’s (1993, 2001, 2007) arguments in favor of aggregate gross output (GO) as a superior macroeconomic aggregate to GDP.

For industries 561 (“Administrative and Support Services”), 42 (“Wholesale Trade”), 531 (“Real Estate”), 44 (“Retail Trade”), and 532 (“Rental and Leasing Services and Lessors of Intangible Assets”) from the LR subsample I substituted the related industries, respectively, 5613 (“Employment Services”), 425 (“Wholesale Trade Agents and Brokers”), 5312 (“Offices of Real Estate Agents and Brokers”), 443111, 4441, & 445110 (“Household Appliance Stores”, “Home Centers”, & “Supermarkets and Other Grocery Stores”), and 5321 (“Automotive Equipment Rental and Leasing”).

Source: US Energy Information Administration (http://www.eia.doe.gov/steo/fsheets/index.cfm).

References

Barnett, W., II, & Block, B. (2006). On Hayekian triangles. Procesos De Mercado: Revista Europea De Economia Politica, 3(2), 39–141.

Callahan, G., & Horwitz, S. (2010). The role of ideal types in Austrian business cycle theory. In R. Koppl, S. Horwitz, & P. Desrochers (Eds.), Advances in Austrian business cycle theory. Bingley: Emerald.

Carlstrom, C. T., & Fuerst, T. S. (2003). The Taylor rule: a guidepost for monetary policy? Economic Commentary, July (http://www.clevelandfed.org/Research/commentary/2003/0703.pdf).

Cochran, J. P. (2001). Capital-based macroeconomics: recent developments and extensions of Austrian business cycle theory. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 4(3), 17–25.

Garrison, R. W. (2001). Time and money: The macroeconomics of capital structure. London: Routledge.

Garrison, R. W. (2005). The Austrian school: Capital-based macroeconomics. In B. Snowdon & H. R. Vane (Eds.), Modern macroeconomics: Its origin, development and current state. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Hayek, F. A. (1933). Monetary theory and the trade cycle. New York: Augustus M. Kelley.

Hayek, F. A. (1935). Prices and production. New York: Augustus M. Kelley.

Keeler, J. P. (2001). Empirical evidence of the Austrian business cycle theory. Review of Austrian Economics, 14(4), 331–351.

Koppl, R. (2002). Big players and the economic theory of expectations. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Koppl, R., & Yeager, L. B. (1996). Big players and herding in asset markets: the case of the Russian ruble. Explorations in Economic History, 33, 367–83.

Kydland, F. E., & Prescott, E. C. (1990). Business cycles: real facts and a monetary myth. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 14, 3–18.

Menger, C. (2007) [1871]. Principles of economics. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Mises, L. (1934). The theory of money and credit. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mulligan, R. F. (2002). A Hayekian analysis of the term structure of production. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 5(2), 17–33.

Prescott, E. C. (1986). Theory ahead of business cycle measurement. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 10, 9–22.

Skousen, M. (1993). Economics on trial. Homewood: Irwin.

Skousen, M. (2001). Beyond GDP: A breakthrough in national income accounting. Ideas on Liberty, April, 53–54.

Skousen, M. (2007). The structure of production with a new introduction. New York: New York University Press.

Taylor, J. B. (1993). Discretion versus policy rules in practice. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 39, 195–214.

Taylor, J. B. (2009). Getting off track: How government actions and interventions caused, prolonged, and worsened the financial crisis. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press.

Young, A. T. (2005). Reallocating labor to initiate changes in capital structures: Hayek revisited. Economics Letters, 89(3), 275–282.

Young, A. T. (2011). Illustrating the importance of Austrian business cycle theory: A reply to Murphy, Barnett, and Block; A call for quantitative study. Review of Austrian Economics, 24(1), 19–28.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I thank an anonymous referee for helpful comments.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Young, A.T. The time structure of production in the US, 2002–2009. Rev Austrian Econ 25, 77–92 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-011-0158-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-011-0158-0

Keywords

- Austrian business cycle theory

- Input-output analysis

- Time structure of production

- Capital structure

- Roundabout methods of production