Abstract

Objective

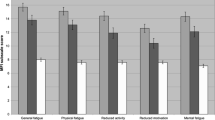

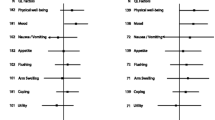

To compare the responsiveness of six questionnaires using three hypotheses of change: (i) change due to supportive-expressive group therapy (SEGT), (ii) improved mood defined as a small effect size (.2) on Profile of Mood States (POMS) Total Mood Disturbance score and (iii) progression of disease.

Method

Data from the “Breast Expressive-Supportive Therapy” study, a multicentre randomized controlled trial of change due to SEGT versus standard of care in women with metastatic breast cancer were used. Questionnaires studied were: POMS, Impact of Event Scale, Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale (PAIS), EORTC QLQ-C30, Mental Adjustment to Cancer and a Pain visual analog scale (VAS). Responsiveness to change was evaluated using the standardized response mean. POMS was used as the standard.

Results

POMS was the most responsive questionnaire to change due to SEGT. Questionnaires measuring psychosocial attributes were responsive to improvement in mood. EORTC QLQ-C30, PAIS, PAIN VAS and MAC were the most responsive to disease progression. More responsive questionnaires were associated with the smallest sample size required to detect an effect.

Conclusions

Responsiveness to change is context specific. The POMS was the most responsive questionnaire to psychosocial therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- POMS:

-

Profile of Mood States

- PAIS:

-

Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- SEGT:

-

Supportive-expressive group therapy

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- MAC:

-

Mental adjustment to cancer

- IES:

-

Impact of Event Scale

- EORTC QLQ-C30:

-

EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30

- TMD:

-

Total Mood Disturbance

- ES:

-

Effect size

- SRM:

-

Standardized response mean

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- INT:

-

Intervention arm

- CTL:

-

Control arm

- DIFF:

-

Difference

References

de Bruin, A. F., Diederiks, J. P., de Witte, L. P., et al. (1997). Assessing the responsiveness of a functional status measure: The sickness impact profile versus the SIP68. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 50, 529–540.

Kirshner, B., & Guyatt, G. (1985). A methodological framework for assessing health indices. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 38, 27–36.

Liang, M. H., Lew, R. A., Stucki, G., et al. (2002). Measuring clinically important changes with patient-oriented questionnaires. Medical Care, 40(4 Suppl), II45–51.

Liang, M. H. (2000). Longitudinal construct validity: establishment of clinical meaning in patient evaluative instruments. Medical Care, 38(9 Suppl), II84–90.

Cella, D., Bullinger, M., Scott, C., et al. (2002). Group vs individual approaches to understanding the clinical significance of differences or changes in quality of life. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 77, 384–392.

Kissane, D. W., Grabsch, B., Love, A., et al. (2004). Psychiatric disorder in women with early stage and advanced breast cancer: A comparative analysis. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 320–326.

Lloyd-Williams, M., & Friedman, T. (2001). Depression in palliative care patients–a prospective study. European Journal of Cancer Care, 10, 270–274.

Zabora, J., BrintzenhofeSzoc, K., Curbow, B., et al. (2001). The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology, 10, 19–28.

Spiegel, D., & Bloom, J. R. (1983). Group therapy and hypnosis reduce metastatic breast carcinoma pain. Psychosomatic Medicine, 45, 333–339.

Spiegel, D., Bloom J. R., & Yalom, I. (1981). Group support for patients with metastatic cancer. A randomized outcome study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 38, 527–533.

Cunningham, A. J., Edmonds, C. V., Jenkins, G. P., et al. (1998). A randomized controlled trial of the effects of group psychological therapy on survival in women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology, 7, 508–517.

Edelman, S., Lemon, J., Bell, D. R., et al. (1999). Effects of group CBT on the survival time of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology, 8, 474–481.

Goodwin, P. J., Leszcz, M., Ennis, M., et al. (2001). The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 345, 1719–1726.

Hewitt, M., Herdman, R., & Holland, J. (Eds.) (2004). Meeting psychosocial needs of women with breast cancer (1st ed., p. 278). Washigton: The National Academy Press.

Bordeleau, L., Szalai, J. P., Ennis, M., et al. (2003). Quality of life in a randomized trial of group psychosocial support in metastatic breast cancer: overall effects of the intervention and an exploration of missing data. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21, 1944–1951.

Classen, C., Diamond, S., Soleman, A., et al. (1993). Brief supportive-expressive group therapy for women with primary breast cancer: A treatment manual. Stanford: Stanford University School of Medicine, p. 55.

McNair D. L. M., & Droppleman, L. F. (1992). EdITS manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, California 92167: EdITS/Educational and industrial testing service.

Goodwin, P. J., Black, J. T., Bordeleau, L. J., et al. (2003). Health-related quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer–taking stock. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 95, 263–281.

Classen, C., Butler, L. D., Koopman, C., et al. (2001). Supportive-expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A randomized clinical intervention trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 494–501.

Taylor, S. E., Lichtman, R. R., Wood, J. V., et al. (1985). Illness-related and treatment-related factors in psychological adjustment to breast cancer. Cancer, 55, 2506–2513.

Watson, M., Greer, S., & Bliss, J. M. (1989) Mental Adjustment to Cancer (MAC) scale users’ manual.

Andritsch, E., Goldzweig, G., Samonigg, H., et al. (2004). Changes in psychological distress of women in long-term remission from breast cancer in two different geographical settings: A randomized study. Support Care Cancer, 12, 10–18.

Watson, M., Haviland, J. S., Greer, S., et al. (1999). Influence of psychological response on survival in breast cancer: A population-based cohort study. Lancet, 354, 1331–1336.

Sundin, E. C., & Horowitz, M. J. (2003). Horowitz’s Impact of Event Scale evaluation of 20 years of use. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 870–876.

Kaasa, S., Malt, U., Hagen, S., et al. (1993). Psychological distress in cancer patients with advanced disease. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 27, 193–197.

Derogatis L. R., McNair D. M., The psychosocial adjustment to illness scale (PAIS & PAIS-SR). Administration, scoring & procedures manual-II. 1990, U.S.A.

Friedman, L. C., Baer, P. E., Nelson, D. V., et al., (1988). Women with breast cancer: Perception of family functioning and adjustment to illness. Psychosomatic Medicine, 50, 529–540.

Merluzzi, T. V., &. Martinez Sanchez. M. A., (1997). Factor structure of the psychosocial adjustment to illness scale (self-report) for persons with cancer. Psychological Assessment, 9, 269–276.

Aaronson, N. K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., et al., (1993). The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85, 365–376.

Bottomley, A., Biganzoli, L., Cufer, T., et al., (2004). Randomized, controlled trial investigating short-term health-related quality of life with Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel versus Doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide as first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer: European organization for research and treatment of cancer breast cancer group, investigational drug branch for breast cancer and the new drug development group study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22, 2576–2586.

McLachlan, S. A., Devins G. M., & Goodwin, P. J. (1998). Validation of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30) as a measure of psychosocial function in breast cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer, 34, 510–517.

Hjermstad, M. J., Fossa, S. D., Bjordal, K., et al., (1995). Test/retest study of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer core quality-of-life questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 13, 1249–1254.

Osoba, D., Rodrigues, G., Myles, J., et al., (1998). Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16, 139–144.

Clark, P., Lavielle P., & Martinez, H., (2003). Learning from pain scales: Patient perspective. The Journal of Rheumatology, 30, 1584–1588.

Cohen J., (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. (2nd ed, p. 567). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Samsa, G., Edelman, D., Rothman, M. L., et al., (1999). Determining clinically important differences in health status measures: A general approach with illustration to the Health Utilities Index Mark II. Pharmacoeconomics, 15, 141–155.

Geels, P., Eisenhauer, E., Bezjak, A., et al., (2000). Palliative effect of chemotherapy: Objective tumor response is associated with symptom improvement in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 18, 2395–2405.

Zou, G. Y., (2005). Quantifying responsiveness of quality of life measures without an external criterion. Quality of Life Research, 14, 1545–1552.

Lemieux, J., Beaton, D. E., S. Hogg-Johnson, et al., (2006). Three methods for minimally important difference: No relationship was found with the net proportion of patients improving. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology (in press).

Schwartz, C. E., Bode, R., Repucci, N., et al., (2006). The clinical significance of adaptation to changing health: A meta-analysis of response shift. Quality of Life Research, 15, 1503–1508.

Holzner, B., Kemmler, G., Sperner-Unterweger, B., et al., (2001). Quality of life measurement in oncology–a matter of the assessment instrument? European Journal of Cancer, 37, 2349–2356.

Wilson, R. W., Hutson L. M., & Vanstry, D. (2005). Comparison of 2 quality-of-life questionnaires in women treated for breast cancer: The RAND 36-Item Health Survey and the Functional Living Index-Cancer. Physical Therapy, 85, 851–860.

Acknowledgements

Dr Lemieux was supported on a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)/Canadian Association of Medical Oncologists/ Rx&D Research fellowship program and Université Laval fellowship program.

Dr Beaton is supported on a CIHR New Investigator’s Award.

The research was funded by the CIHR and the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Alliance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9253-x

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lemieux, J., Beaton, D.E., Hogg-Johnson, S. et al. Responsiveness to change to change due to supportive-expressive group therapy, improvement in mood and disease progression in women with metastatic breast cancer. Qual Life Res 16, 1007–1017 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9208-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9208-2