Abstract

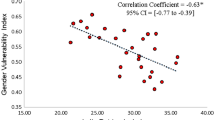

In multi-level and multi-layered foundations of gendered approaches for understanding the kinship system, family-building behavior, son preference, and male-skewed child sex ratios in India; patriarchy and patrilineality have received greater attention than patrilocality. To fill this gap, we construct a measure of patrilocality and hypothesize that households practice sex selection and daughter discrimination because of patrilocality norms that dictate the later life co-residence between parents and sons. Our findings reveal that the child sex ratio, sex ratio at birth, and sex ratio at last birth are negatively correlated with patrilocality rates across states and districts of India. The robustness of these findings is verified by using alternative definitions of patrilocality, examining the association between patrilocality and patrilineality, and assessing the relationship between patrilocality and child sex ratios across states and by urbanization levels. We conclude that, in the absence of strong social security measures and a lack of preference for old-age homes, amidst the accepted practice of patrilocality coupled with increasingly lower fertility norms, the dependency on sons will continue, leading to the continuation of sex selection in India.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data used in this study will be made available upon request from the authors.

Notes

Das Gupta (1987) documented this observation in highly well-to-do landowners of Punjab who were not far behind landless people in terms of female mortality and selective discrimination; their women preferring half a daughter vis-à-vis little less than two sons.

Female autonomy as described by Dyson and Moore (1983) is the control over one’s own private space and ability— mental, social, and practical—to influence it through the needed information.

These are different from the natural factors highlighted by Miller (1989) that keep the sex-ratios biologically skewed at two stages- (1) Sex-ratios tend to be high at birth, about 105, but this skewness fades away in a year due to rather high natural mortality rates of a male child compared to a female child in first year of birth, (2) Females have comparatively high mortality at their reproductive ages due to pregnancy and childbirth related complexities.

References

Agarwal, B. (1986). Women, Poverty and Agricultural Growth in India. Journal of Peasant Studies, 13, 165–220.

Agarwal, B. (2002). Are we not peasants too? Land rights and women’s claims in India. SEEDS no. 21. New York: Population Council.

Agnihotri, S. B. (2000). Sex ratio patterns in the Indian Population. Sage.

Agnihotri, S. B. (2003). Survival of the girl child: Tunnelling out of the Chakravyuha. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(41), 4351–4360.

Agnihotri, S., Palmer-Jones, R., & Parikh, A. (2002). Missing women in Indian districts: A quantitative analysis. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 13, 285–314.

Allendorf, K. (2013). Going Nuclear? Family Structure and Young Women’s Health in India, 1992–2006. Demography, 50, 853–880. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/42919903

Arnold, F., Kishor, S., & Roy, T. K. (2002). Sex-selective abortions in India. Population and Development Review, 28(4), 759–785.

Arokiasamy, P. (2007). Sex ratio at birth and excess female. Child mortality in India: Trends differentials and Regional patterns. In I. Attané, Z. C, & Guilmoto (Eds.), Watering the. Neighbour’s Garden: The Growing Demographic Female Deficit in Asia (pp. 49–72). Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography.

Arokiasamy, P., & Goli, S. (2012a). Explaining the Skewed child sex ratio in rural India: Revisiting the landholding-patriarchy hypothesis. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(42), 85–94.

Arokiasamy, P., & Goli, S. (2012b). Provisional results of the 2011 Census of India: Slowdown in growth, ascent in literacy, but more missing girls. International Journal of Social Economics, 39(10), 785–801.

Barik, D., Agrawal, T., & Desai, S. (2015). After the dividend: Caring for a Greying India. Economic and Political Weekly, 50(24), 108–112.

Basu, D., & Jong, R. D. (2010). Son targeting fertility behavior: Some consequences and determinants. Demography, 47(2), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0110

Berkman, L. F., Sekher, T. V., Capistrant, B., & Zheng, Y. (2012). Social networks, family, and caregiving among older adults in India. Aging in Asia: Findings from new and emerging data initiatives. National Academies.

Bhat, P. N. (2002). On the trail of ‘Missing’ Indian females: II: Illusion and reality. Economic and Political Weekly, 37(52), 5244–5263.

Bhat, P. N., & Zavier, A. J. (2007). Factors influencing the use of prenatal diagnostic techniques and the sex ratio at Birth in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(24), 2292–2303.

Bhat, P. N., & Zavier, A. J. (2003, November). Fertility decline and gender bias in northern India. Demography, 40(4), 637–657.

Boer, A., & Hudson, V. (2017). Patrilineality, Son Preference, and sex selection in South Korea and Vietnam. Population and Development Review, 43(1), 119–147.

Bongaarts, J. (1987). Does family planning reduce infant mortality rates? Population and Development Review, 13(2), 323–334.

Bongaarts, J., & Guilmoto, C. Z. (2015). June). How many more Missing women? Excess female mortality and prenatal sex selection, 1970–2050. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 241–269.

Chakravorty, S., Goli, S., & James, K. S. (2021). Family Demography in India: Emerging patterns and its challenges. Sage Open, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211008178

Chao, F., Guilmoto, C. Z., C., S. K., & Ombao, H. (2020). Probabilistic projection of the sex ratio at birth and missing female births by State and Union Territory in India. Plos One, 15(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236673

Chaudhuri, S. (2012). The Desire for sons and excess fertility: A Household-Level analysis of parity progression in India. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38(4), 178–186.

Clark, S. (2000). Son Preference and Sex Composition of children: Evidence from India. Demography, 37(1), 95–108.

Coale, A. J. (1991). Excess female mortality and the balance of sexes: An Estimate of the number of ‘Missing females’. Population and Development Review, 17(1), 35–51.

Croll, E. (2000). Endangered daughters: Discrimination and development in Asia. Routledge.

Das Gupta, M. (1987). Selective discrimination against female children in Punjab, India. Population and Development Review, 13(1), 77–100.

Das Gupta, M. (2019). Is banning sex-selection the best approach for reducing prenatal discrimination? Asian Population Studies, 15(3), 319–336.

Das Gupta, M., & Bhat, P. N. (1997). Fertility decline and increased manifestation of Sex Bias in India. Population Studies, 51(3), 307–315.

Das Gupta, M., Lee, S., Uberoi, P., Wang, D., Wang, L., & Zhang, X. (2000). State Policies and Women’s Autonomy in China, India, and the Republic of Korea, 1950–2000: Lessons from Contrasting Experiences (Policy Research Working Paper Series 2497), The World Bank. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/wbk/wbrwps/2497.html

Das Gupta, M., Zhenghua, J., Bohua, L., Zhenming, X., Chung, W., & Hwa-Ok, B. (2003). Why is Son Preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A Cross-country Study of China, India, and the Republic of Korea. Journal of Development Studies, 40(2), 153–187.

Dee, T. S. (2004). Are there civic returns to education? Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 1697–1720.

Desai, S., Dubey, A., Joshi, B. L., Sen, M., Shariff, A., & Vanneman, R. (2012). India Human Development Survey-2. University of Maryland.

Dube, L. (1988). On the construction of gender: Hindu girls in patrilineal India. Economic and Political Weekly, 23(18), WS11–WS19.

Duflo, E. (2012). Women empowerment and Economic Development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4), 1051–1079.

Dyson, T. (2012). Causes and consequences of skewed sex ratios. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145429

Dyson, T., & Moore, M. (1983). On Kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behavior in India. Population and Development Review, 9(1), 35–60.

Ebenstein, A. (2014). Patrilocality and Missing Women Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2422090 orhttps://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2422090

Ebenstein, A. (2021). Elderly Coresidence and Son Preference: Can Pension Reforms Solve the ‘Missing Women Problem? Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3829866 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3829866

Ebenstein, A., & Leung, S. (2010). Son preference and access to social insurance: Evidence from China’s rural pension program. Population and Development Review, 36(1), 47–70.

Eisenstein, Z. R. (1979). Capitalist patriarchy and the case for socialist feminism. Monthly Review.

Engels, F. (2004). The origin of the family, private property and the state. Resistance Books.

Filser, A., Barclay, K., Beckley, A., Uggla, C., & Schnettler, S. (2021). Are skewed sex ratios associated with violent crime? A longitudinal analysis using Swedish register data. Evolution and Human Behavior, 42(3), 212–222.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2007). Characteristics of Sex-Ratio Imbalance in India, and Future Scenarios. 4th Asia Pacific Conference on Reproductive and Sexual Health and Rights Hyderabad: UNFPA.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2009). September). The sex ratio transition in Asia. Population and Development Review, 35(3), 519–549.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2012a). Sex imbalances at birth: Current trends, consequences and policy implications. UNFPA Asia and the Pacific Regional Office.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2012b). Son preference, sex selection, and kinship selection, and kinship. Population and Development Review, 38(1), 31–54.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2015). Mapping the diversity of gender preferences and sex imbalances in Indonesia in 2010. Population Studies, 69(3), 299–315.

Guilmoto, C. Z., & Depledge, R. (2008). Jan. - Mar.). Economic, Social and spatial dimensions of India’s excess child masculinity. Institut National d’Etudes Démographiques, 63(1), 91–117.

Haddad, L., & Kanbur, R. (1990). How Serious is the neglect of Intra-household Inequality? The Economic Journal, 100, 866–888.

Hesketh, T., Lu, L., & Xing, Z. W. (2011). The consequences of son preference and sex-selective abortion in China and other Asian countries. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 183(12), 1374–1377.

Hudson, V. M., Bowen, D. L., & Nielsen, P. L. (2011). December). What is the relationship between Inequity in Family Law and Violence against women? Approaching the issue of legal enclaves. Politics and Gender, 7(4), 453–492.

Hudson, V. M., Bowen, D. L., & Nielsen, P. L. (2015). August). Clan Governance and State Stability: The relationship between female subordination and political order. American Political Science Review, 109(3), 535–555.

James, K. S., Rajan, S. I., & Goli, S. (2020). Demographic and health diversity in the era of SDGs. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(6), 46–52.

Jayachandran, S. (2015). The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Annual Review of Economics, 7, 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115404

Jayaraj, D., & Subramanian, S. (2004). Women’s wellbeing and the sex ratio at birth: Some suggestive evidence from India. Journal of Development Studies, 40(5), 91–119.

Jha, P., Kumar, R., Vasa, P., Dhingra, N., Thiruchelvam, D., & Moineddin, R. (2006). Low Male-To-Female sex ratio of Children Born in India: National Survey of 1·1 million households. The Lancet, 367(9506), 211–218.

Jha, P., Kesler, M. A., Kumar, R., Ram, F., Ram, U., Aleksandrowicz, L., & Banthia, J. K. (2011). Trends in selective abortions of girls in India: Analysis of nationally representative birth histories from 1990 to 2005 and census data from 1991 to 2011. The Lancet, 377(9781), 1921–1928.

John, M. E. (2018). The political and social economy of sex selection: Exploring family development linkages. UNFPA and UNWomen.

Kaur, R. (2020). Gender and demography in Asia (India and China). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Retrieved from https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-345

Kaur, R., & Vasudev, C. (2019). Son Preference and Daughter Aversion in two villages of Jammu. Economic and Political Weekly, 54(13), 13–16.

Kaur, R., Bhalla, S., Agarwal, M. K., & Ramakrishnan, P. (2016). Sex ratio at Birth: The role of gender, Class, and Education. UNFPA.

Khalil, U., & Mookerjee, S. (2019). Patrilocal Residence and Women’s Social Status: Evidence from South Asia. Economic Development and Cultural Change. University of Chicago Press, 67(2), 401–438.

Kim, M. (2010). Gender and International Marriage Migration. Sociology Compass, 4(9), 718–731.

Kishor, S. (1993, April). May God give sons to all: Gender and child mortality in India. American Sociological Review, 58(2), 247–265.

Kishor, S., & Gupta, K. (2009). Gender equality and women’s empowerment in India. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) India 2005-06. International Institute for Population Sciences.

Kulkarni, P. M. (2007). Estimation of missing girls at birth and juvenile ages in India. Paper commissioned by United Nations Population Fund – UNFPA. Retrieved from https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/UNFPA_Publication-39767.pdf

Kulkarni, P. M. (2012). India’s child sex ratio: Worsening Imbalance. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, IX(2), 112–114.

Kulkarni, P. M. (2020). Sex ratio at Birth in India- recent trends and patterns. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

Kumar, S., & Sathyanarayana, K. M. (2012). District-Level estimates of fertility and implied sex ratio at Birth in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(33), 66–72.

Kumari, A., & Goli, S. (2021). Skewed child sex ratios in India: A revisit to geographical patterns and socio-economic correlates. Journal of Population Research, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-021-09277-x

Kuntla, S., Goli, S., & Jain, K. (2014). Explaining sex differentials in child mortality in India: Trends and determinants. International Journal of Population Research. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/649741.sz. Article ID 649741.

Malhotra, A., Vanneman, R., & Kishor, S. (1995). Fertility, dimensions of patriarchy, and development in India. Population and Development Review, 21(2), 281–305.

Miller, B. D. (1989). June). Changing patterns of Juvenile Sex Ratios in Rural India, 1961 to 1971. Economic and Political Weekly, 24(22), 1229–1236.

Murthi, M., Guio, A. C., & Dreze, J. (1995). Mortality, fertility, and gender Bias in India: A District-Level analysis. Population and Development Review, 21(4), 745–782.

Nandi, A., & Deolalikar, A. B. (2013). Does a legal ban on sex-selective abortions improve child sex ratios? Evidence from a policy change in India. Journal of Development Economics, 103, 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.02.007

Palriwala, R., & Uberoi, P. (2008). Exploring the links: Gender issues in marriage and migration. Marriage Migration and Gender, 23–60.

Pande, R. P., & Astone, N. M. (2007). Explaining son preference in rural India: The independent role of structural versus individual factors. Population Research and Policy Review, 26(1), 1–29.

Petraitis, P. S., Dunham, A. E., & Niewiarowski, P. H. (1996). Inferring multiple causality: The limitations of path analysis. Functional Ecology, 10(4), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.2307/2389934

Raju, S. (2011). Gendered geographies: Space and place in South Asia. Oxford University Press.

Rammohan, A., & Vu, P. (2018). Gender inequality in education and kinship norms in India. Feminist Economics, 24(1), 142–167.

Retherford, R., & Choe, M. (2011). Statistical models for causal analysis. Wiley.

Retherford, R. D., & Roy, T. K. (2003). Factors affecting sex-selective abortion in India and 17 major states. National Family Health Survey Subject Report Number 21. Retrieved from https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/f5085e17-cdaa-4cfd-9e7e-7dc2a09c76ec/content

Robitaille, M. C., & Chatterjee, I. (2018). Sex-selective abortions and infant mortality in India: The role of parents’ stated son preference. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(1), 47–56.

Rosenblum, D. (2013). The effect of fertility decisions on excess female mortality in India. Journal of Population Economics, 26(1), 147–180.

Saurabh, S., Sarkar, S., & Pandey, D. K. (2013). Female literacy rate is a better predictor of birth rate and infant mortality rate in India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 2(4), 349.

Sekher, T. V. (2010). Special Financial Incentive Schemes for the Girl Child in India: A Review of Select schemes, United Nations Population Fund, New Delhi. Retrieved from https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/UNFPA_Publication-39772.pdf

Sekher, T. V. (2012). Ladlis and Lakshmis: Financial Incentive Schemes for the Girl Child in India, Economic and Political Weekly, 47 (17).

Sekher, T. V., & Hatti, N. (2010). Disappearing daughters and intensification of gender bias: Evidence from two village studies in South India. Sociological Bulletin, 59(1), 111–133.

Sen, A. (1989). Women’s survival as a development problem. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 43(2), 14–29.

Sharrow, D., Hug, L., Liu, Y., & You, D. (2020). Levels & Trends in Child Mortality United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/media/79371/file/UN-IGME-child-mortality-report-2020.pdf.pdf

South, S. J., Trent, K., & Bose, S. (2014). Skewed sex ratios and criminal victimization in India. Demography, 51(3), 1019–1040.

Srinivasan, S., & Bedi, A. S. (2008). Daughter elimination in Tamil Nadu, India: A tale of two ratios. The Journal of Development Studies, 44(7), 961–990.

Sudha, S., & Irudaya, R. (1999, January). Female demographic disadvantage in India 1981–1991: Sex-selective abortions and female infanticide. Development and Change, 30(3), 585–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00130

Sundaram, A., & Vanneman, R. (2008). Gender differentials in literacy in India: The intriguing relationship with women’s Labor Force participation. World Development, 36(1), 128–143.

Tafuro, S., & Guilmoto, C. Z. (2020, February). Skewed sex ratios at birth: A review of global trends. Early Human Development, 141, 104868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104868

UNDP (2014). Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience Human Development Report, UNDP. Retrieved from https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2014

Unisa, S., Pujari, S., & Usha, R. (2007). Sex-Selective Abortion in Haryana: Evidence from Pregnancy History and Antenatal Care. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(1), 60–66. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4419111

Visaria, P. M. (1967). The sex ratio of the population of India and Pakistan and regional variations during 1901-61. In A. Bose (Ed.), Patterns of Population Change in India, 1951-61 (pp. 334–371). Allied.

Zavier, A. J., & Bhat, P. N. (2007). Factors influencing the use of prenatal diagnostic techniques and the sex ratio at Birth in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(24), 2292–2303.

Acknowledgements

The authors immensely benefited from extensive comments and suggestions on the first draft by Professor Monica Das Gupta, University of Maryland, Professor Christopher Guilmoto, Ined-IRD, Mary E. John, CWDS, New Delhi and Colleagues at the UWA Economics Unit. We also thank Professor P.M. Kulkarni, Jawaharlal Nehru University, and Professor K.S. James, IIPS for helpful discussions on the topic. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers, as well as Kara Joyner, the Editor-in-Chief of Population Research and Policy Review, for their excellent comments and suggestions, which significantly improved the manuscript. The authors are solely responsible for any remaining errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

This paper did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Goli, S., Arora, S., Jain, N. et al. Patrilocality and Child Sex Ratios in India. Popul Res Policy Rev 43, 54 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-024-09897-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-024-09897-0