Abstract

My aim in this paper is to show how the problem of inflated effect sizes (the Winner’s Curse) corrupts the severity measure of evidence. This has never been done. In fact, the Winner’s Curse is barely mentioned in the philosophical literature. Since the severity score is the predominant measure of evidence for frequentist tests in the philosophical literature, it is important to underscore its flaws. It is also crucial to bring the philosophical literature up to speed with the limits of classical testing. The Winner’s Curse is one of them. The problem is that when a significant result is obtained by using an underpowered test, the severity score becomes particularly high for large discrepancies from the null-hypothesis. This means that such discrepancies are very well supported by the evidence according to that measure. However, it is now well documented that significant tests with low power display inflated effect sizes. They systematically show departures from the null hypothesis H0 that are much greater than they really are. From an epistemological point of view this means that a significant result produced by an underpowered test does not provide evidence for large discrepancies from H0. Therefore, the severity score is an inadequate measure of evidence. Given that we are now aware of the phenomenon of inflated effect sizes, it would be irresponsible to rely on the severity score to measure the strength of the evidence against the null. Instead, one must take appropriate measures to try and avoid using underpowered tests by setting a threshold for the sample size or by replicating the results of the experiment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I have searched with the key words “winner’s curse” on the springer journal , the Oxford academic journal and on the university of Chicago press journal websites, with a filter on philosophy journals. I have also searched for the same key words on the Philpaper website. I only found one relevant reference and it is not in connection with the severity score: (Vieland and Chang 2018).

First of all, a test statistic always displays a departure from what we expect under H0 when the test is significant with a small \(\alpha\) (0.05). This is because the probability of a statistic reaching the critical region is as small as \(\alpha\). Now, let us imagine that the power is low (0.08) and also claim that a test statistic does not display a departure from that we expect under H1 when the test is significant. This means that we would expect the test statistic to reach the critical region under H1. But we just said that we do not expect this to be the case. The probability is 0.08. Therefore, it is impossible for a significant result to fail to display a departure from what we expect under both H0 and H1.

References

Button, K. S., Ioannidis, J. P., Mokrysz, C., Nosek, B. A., Flint, J., Robinson, J. E. S., et al. (2013). Power failure: Whysmall sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(5), 365–376.

Gelman, A., & Carlin, J. (2014). Beyond power calculations assessing type s (sign) and type m (magnitude) errors. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(6), 641–651.

Ioannidis, J. P. (2008). Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology, 19(5), 640–648.

Ioannidis, J. P. A., Stanley, T. D., & Doucouliagos, H. (2017). The power of bias in economics research. The Economic Journal, 127(605), F236–F265.

Mayo, D. G., & Spanos, A. (2006). Severe testing as a basic concept in a Neyman–Pearson philosophy of induction. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 57(2), 323–357.

Mayo, D. G., & Spanos, A. (2011). Error statistics. Philosophy of Statistics, 7, 152–198.

Spanos, A. (2013). Who should be afraid of the Jeffreys-Lindley paradox? Philosophy of Science, 80(1), 73–93.

Vieland, V. J., & Chang, H. (2018). No evidence amalgamation without evidence measurement. Synthese, 196(8), 3139–3161.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The test with 10 observations per group

We find the severity score for a difference strictly larger than (0.1).

We find the distributions of the p-value under the assumption that H1 is true for the test with 10 observations per group

We perform a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for the uniformity of the p-values under H1.

Extra simulations

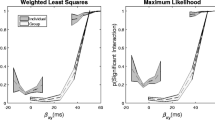

We perform a low powered test with a difference of 0.4 and compute the mean severity for a discrepancy of 0.4.

We then perform a low powered test with a difference of 0.1 and compute the mean severity for a discrepancy of 0.4. We see that the mean severity score is larger than the previous one. This means that we can better justify a discrepancy that is 4X larger than the truth (0.1) than a true discrepancy of 0.4 when the power is low.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rochefort-Maranda, G. Inflated effect sizes and underpowered tests: how the severity measure of evidence is affected by the winner’s curse. Philos Stud 178, 133–145 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01424-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01424-z